|

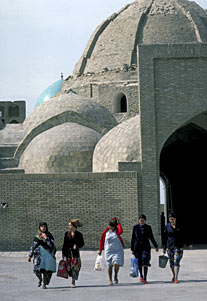

Uzbek women in Bukhara, and, below, in Samarkand.

|

|

he rigors of our journey along the Silk Roads were beginning to take their toll. A ruddy-faced Englishman - his wife referred to him as "The General" - had been flown home after an unsecured upper bunk fell on his head. A white-haired Englishwoman, now slumped in a faint in the hotel lobby, would be the next to go.

he rigors of our journey along the Silk Roads were beginning to take their toll. A ruddy-faced Englishman - his wife referred to him as "The General" - had been flown home after an unsecured upper bunk fell on his head. A white-haired Englishwoman, now slumped in a faint in the hotel lobby, would be the next to go.

This was Thursday, so it must be Baku, but at five o'clock in the morning no one seemed to care - least of all the bus drivers detailed to collect us.

We squeezed into another group's bus to the airport, and were further compressed in an Aeroflot jet flying over the Caspian Sea: Though our journey that day was aerial and hardly "golden," we were now on the Golden Road to Samarkand.

This important section of the Silk Roads got its name, according to British poet and diplomat James Elroy Flecker, because it was "a desert path as yellow as the bright sea-shore," which led from Mesopotamia to "divine Bukhara and happy Samarkand," great centers of religion and learning under the Samanid and Timurid rulers of Central Asia. "Therefore the pilgrims call it The Golden Journey."

By the time we touched down in Bukhara the hardier members of our group had revived sufficiently to join in the folk dancing which greeted us.

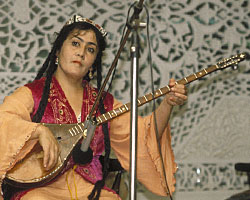

Although we were now in Central Asia, in the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan, the folk-dancing group was very similar to those we had seen in Turkey. The Uzbeks, like most of the peoples of Central Asia, share the ancestry of the Turks of Turkey.

The Turks' original homeland was the Altai Mountains in Mongolia. Nomads, with what seems to have been a penchant for raiding other peoples' territory, they controlled by the sixth century a vast swathe of steppeland stretching nearly from the Pacific Ocean to the Black Sea.

As they fanned out across the steppes, tribal divisions among the Turks became more pronounced; by the eighth century such groups as the Kirghiz and Uygurs had their own kingdoms (See Aramco World, July-August 1985).

|

|

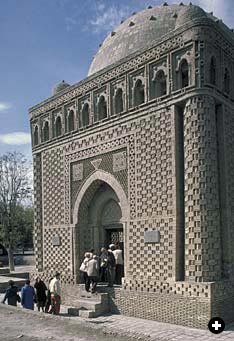

| Two examples of decorative Bukhara brickwork: left, the 10th-century Samanid mausoleum and, right, the 12th-century Kalayan minaret. |

Meanwhile, the riches of the Silk Roads brought wave after wave of Turkic invaders, including the Uzbeks, down onto the plains of Central Asia, where they encountered and eventually adopted Islam.

In the 11th century the Seljuq Turks swept west into today's Iran, Iraq and Syria, and then Anatolia, while Tatars - Turkic troops fighting under Ghengis Khan - occupied the Crimea. Finally came the Osmanli Turks, who ultimately established the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia and the Balkans, North Africa and the Middle East.

|

In the course of their migrations the Turks absorbed and intermarried with many other peoples. Because of this there is a striking variation in their physical appearance: Aegean Turks, for example, look typically Mediterranean, while Kazaks of the Heavenly Mountains resemble Chinese. But their culture, with some regional variations, remains one - especially their music and dance. And it is still possible for a Turkish-speaker to make himself understood almost from one end of the Silk Roads to the other.

Turks were sufficiently dominant in Central Asia to lend it the name Turkestan, but the region was also subject to China under the Han (206 BC-AD 220) and the early Tang (618-907) Dynasties, while at other times the Arabs and Mongols ruled much of the region. In the 19th century it fell under the control of Czarist Russia, and later of the Soviets.

All have left their cultural stamp upon it, with the result that today one can see in its cities smart Red Army soldiers and colorful cloth-swathed Uzbek women visiting Arab mosques and Mongol mausoleums together with the region's latest invaders - foreign tourists.

This mixed culture of Central Asia results as much from the influences brought by the Silk Roads as from the powers that sought to control the trade that flowed along them. For there was an enormous amount of lucrative traffic in this region - another reason why it was called the Golden Road..

|

Eleven caravan trails crossed at Bukhara. Bustling bazaars grew up throughout the city, the most important ones located near the gates that served these routes, and near places of worship where people always gathered.

Today a domed bazaar still buzzes near Bukhara's main religious complex: a small square where the massive tiled portals of a mosque and a functioning madrasa, or Muslim religious school, face each other. (Few such schools still operate in the USSR today.) Between them towers the unusual free-standing Kalayan minaret, its honey-colored bricks laid in protruding and receding patterns to produce a texture like that of an elaborately knitted sweater. Built in 1127, the minaret rises to a height of nearly 45 meters (150 feet); when Bukhara was at war - which was much of the time - it was used as a watchtower.

An even earlier example of intricate decorative brickwork is the 10th-century tomb of the Persian Samanid rulers, who made Bukhara their capital. Buried for centuries, the Samanid mausoleum was rediscovered in 1930 during landscaping of the Kirov Park of Rest and Culture and, according to our Intourist guide, was restored using bricks made of clay bound with egg yoke and camel's milk, to match the originals.

Our guide also took us to what she said was "part of the original Silk Route" - a paved pedestrian mall running parallel to an ancient canal and through a domed gateway-like building.

"The merchants entered the market through this trading dome," she said, "where they changed their money, then passed through three other trading domes - one for hats, one for silk and one for jewelry - to the market place."

|

| Samarkand's rain-swept Registan, Central Asia's noblest square. |

Could we actually have been standing on one of the Silk Roads? We cannot be certain, for their exact locations have been erased by time. Even their name is a modern invention. For although silk accounted for 90 percent of Rome's and much of Byzantium's imports from China, no mention of a "silk road" or of "silk routes" is made in ancient or medieval texts. Not until 1877, in fact, did geographer and geologist Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen of Bonn University christen them Seidenstraßen.

|

|

| Bukhara market is still colorful, but its silks are synthetic. |

Although silk undoubtedly provided the impetus for East-West trade, it was not the only cargo carried by the plodding caravans. From the East they also bore the gems and spices of India, the furs and skins of Siberia, and the porcelain and lacquer-ware of China; from the West they carried cosmetics and perfumes from Egypt and Arabia, ivory from Africa, amber from the Baltic, glassware from Syria and gold and silver from Constantinople and Rome.

And all these goods were bartered, bought and sold in the teeming bazaars of Bukhara and Samarkand.

|

An Uzbek dancer entertaining a group of tourists, Bukhara's latest and most profitable "invaders."

|

Today, Bukhara's main market is relegated to the suburbs - hard by the crumbling remains of the wall, 12 kilometers long and 10 meters high (7.4 miles long and 32 feet high), that once ringed the city. Gaily-colored fabrics are its most popular item, but its "silks" are factory-made synthetics, and there is no bargaining over the state-fixed price.

No longer a center of trade or pilgrimage, Bukhara owes its present prosperity to tourism and to nearby deposits of natural gas. Its mosques, once so numerous that the devout could pray in a different one each day of the year, are mostly gone. And few of the ones that remain - although carefully restored and maintained as monuments - are functioning as religious centers.

Samarkand, Bukhara's continued rival for leadership of the region, has also experienced changing fortunes. Destroyed by Ghengis Khan in 1220, then rebuilt in the 14th century by Tamerlane to become the most important economic and cultural center in Central Asia, it suffered severe economic decline following the demise of overland East-West trade. From the 1720's to the 1780's, indeed, it was uninhabited. Only in 1876, after the railroad along which we were now traveling reached there, did the city revive.

|

| An old man leaving one of Bukhara's few functioning mosques. |

The end of our journey to Samarkand was even less golden than the start. At least in Bukhara the sun had been shining; in Sam3arkand it was pouring with rain. But even leaden skies failed to dim the luster of the thousands of blue-glazed tiles with which Tamerlane, lord of Asia from the Great Wall to the Urals, covered his capital. The rain, in fact, seemed to give the tiles added sparkle, while red, green and yellow umbrellas made contrasting color splashes among the sea of blues.

But Tamerlane, who died in 1405 - our guide refused at this stage to say of what is not buried surrounded by his favorite color, but rather beneath a massive monolith of dark green jade, below a dome gilded with three kilograms (96 troy ounces) of gold. "If I were alive," says a grim inscription in an anteroom of his mausoleum, "people would not be glad." Possibly: After one victory Tamerlane made a pyramid of 70,000 enemy heads.

|

|

|

| Left, a red umbrella contrasts colorfully with Samarkand's blue-tiled domes; middle, an Uzbek child; right, Shah-i-Zinda royal cemetery Samarkand. |

Tamerlane's descendants made Samarkand a center of science and art. His grandson Ulugh Beg, using an enormous sextant set in a hillside overlooking the city plotted, without the aid of a telescope, the positions of over 1,000 stars. The map of the heavens he drew was used as the basis for a later Gregorian star chart, and was also adopted by Chinese astrologers.

The royal astronomer also built, and lectured at, the first of the trio of great religious schools which today command three of the four sides of the Registan-Central Asia's noblest square.

As might be expected, the tiled facade of Ulugh Beg's madrasa is decorated with enormous star patterns. Opposite, and clearly built to harmonize, is the Shirdar, or "lion-bearing," Madrasa, so called because of the tiger in the rays of the rising sun which decorate its portal. On the north side of the square is the Tilakar, or "gilded," Madrasa, named after the large quantities of gold used in its decoration.

The south side of the magnificently restored Registan is open to the wind and, on the day of our visit, to the sweeping rain. As we prepared to leave Samarkand, our clothes still damp from repeated soakings, our impish Intourist guide finally admitted how Tamerlane had died: of pneumonia on his way, like us, to China.

|

Tamerlane's death marked the beginning of the end of the Silk Roads. His successors lacked the ruthlessness to hold together the vast steppe empire created by the Turks, enlarged by the Mongols and perpetuated by Tamerlane. Tribes revolted and political instability set in - followed by economic depression and cultural decline. Weak and disorganized, Central Asia was no longer capable of playing the role of intermediary vital to continued East-West trade.

Meanwhile, with the fall of the Mongol sovereigns in China and the refounding of a purely Chinese dynasty in 1386, China began closing herself off in an attempt to expunge long years of foreign domination and resuscitate traditional Chinese values.

In 1426, Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty closed China's borders to the northwest. After 1,500 years as a main artery between East and West, the Silk Roads were finally cut.

< Previous Story | Next Story >