Written by John Lawton

In the spread of Islam to the East, sea routes were of paramount importance. Riding the monsoon winds across the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean, Arab naval expeditions incorporated new lands into the Islamic realm, while Arab traders who settled in ports en route founded Muslim communities, seed crystals for widespread conversion.

|

| The UNESCO flag flies crisply over Oman's royal yacht as it crosses the Arabian Sea to a colorful welcome from Pakistani fishermen (below) in the Indus estuary. |

|

It was in the wake of these zealous seafarers that Wheeler and I now set sail from Muscat aboard Oman's royal yacht, the Fulk al-Salamah, lent by Sultan Qaboos to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for a voyage retracing the ancient maritime trading routes to Southeast Asia.

The voyage was part of UNESCO's project "Integral Study of the Silk Roads: Roads of Dialogue," whose main purpose is to draw attention to the importance of ancient trade routes in contacts between nations. And our fellow passengers were geographers, historians, archeologists and maritime experts from around the world who were to present papers on the history of trade, navigation and religion in seminars at ports en route. For it was not only merchants and their wares that traveled the Silk Roads, the network of ancient trade routes linking Europe and China. Some of the world's basic technologies, greatest inventions and most universal religions, including Islam, were transmitted vast distances on these land and sea routes.

Setting sail from Muscat's modern container terminal of Mina Qaboos to the incongruous strains of "Scotland the Brave," played by the pipe and drum band of the Omani Royal Naval Squadron, we arrived in Karachi two days later to a more indigenous welcome: Scores of flag-decked wooden fishing boats escorted us up the Indus Estuary to a dockside reception of traditional music and dance performed by men in bright orange turbans at Port Bin Qasim - named after Muhammad ibn al- Qasim, the teenaged Arab general who brought Islam to Pakistan.

After the murder of the third caliph, 'Uthman ibn 'Affan, in 656, the election of the Prophet's son-in-law 'AH ibn Abi Talib was challenged by Mu'awiyah, nephew of 'Uthman and governor of Syria. 'Ali was assassinated and Mu'awiyah rose to power, founding in 661 a hereditary caliphate, the Umayyad Dynasty, which, from its capital at Damascus, ruled the Islamic state for over a century, rekindling the spirit of expansion.

In 711, the Umayyads sent an expedition by sea under 17-year-old Muhammad ibn al-Qasim, to suppress pirates who were preying on Arab shipping in the Indus Delta, while almost simultaneously another Arab general, Qutaybah ibn Muslim, crossed the Oxus River into Central Asia.

According to the eighth-century account in the Shah-nama, Muhammad ibn al-Qasim commanded a force of 15,000 infantry, plus horse and camel cavalry, and was armed with five catapults, the largest of which took 500 men to operate. The garrison at Debal, at the mouth of the Indus River, surrendered - quickly followed by other cities of the lower Indus valley, which is now the Pakistani province of Sind.

Archeologists have identified the ancient remains of a port city at Banbhore, 64 kilometers (40 miles) from Karachi, as the site of Debal, which fell to Muhammad ibn al-Qasim in 712. So Wheeler and I hired a car and set off on what was to be the first of many seemingly suicidal road journeys across the Indian subcontinent in search of Islam's path east.

|

| Although little remains of what is believed to be the first mosque on the Indian subcontinent, built in 727 at Banbhore, the bases of some of the pillars that once supported its prayer hall are still visible. |

|

The most impressive remains at Banbhore are the eighth-century city walls, built of limestone blocks, with semicircular bastions at regular intervals. But, from our viewpoint, the most interesting were those of the mosque, dating from 727and said to be the earliest on the subcontinent. About 40 meters (130 feet) square and consisting of an open courtyard surrounded by covered cloisters on three sides and a prayer chamber on the fourth, the foundations and floor of the mosque are still clearly visible. So are many of the bases of the 33 pillars which, in three rows, once supported the roof of the prayer chamber.

Today Banbhore stands deserted on the northern shore of the obscure Gharo Creek, centuries of silting and occasional earthquakes having altered the course of the Indus and driven back the sea.

A small museum nearby, however, helps give the visitor some idea of what the port was like in its heyday, and the display of pottery and coins indicates it once traded with Muslim countries to the west, and with territories as far east as China.

While Muhammad ibn al-Qasim was subjecting Sind, Qutaybah ibn Muslim was conquering Central Asia. Crossing the Oxus in 711, he captured the legendary caravan cities of Bukhara and Samarkand, then Sogdian strongholds astride the ancient Silk Roads and now situated in Soviet Uzbekistan.

Legend relates that, on the arrival of Qutaybah's forces outside Samarkand, the Sogdians shouted from the ramparts that the Arabs were wasting their time. "We have found it written," they said, "that our city can only be captured by a man named 'Camel-Saddle.'" Being ignorant of Arabic, they did not know that that was precisely what Qutaybah's name meant.

Pushing even further east, Qutaybah occupied the Ferghana Valley and, in 713, marched across the Tian Shan (Heavenly Mountains) which protect China from the West, and took Kashgar.

By the middle of the eighth century, when the Abbasids replaced the Umayyads as rulers of the Islamic empire, most of Central Asia had been incorporated into the Muslim realm, and the second phase of expansion was all but complete.

The Muslims' Central Asian conquests, however, had put them on a collision course with China, which was now in a period of vigorous expansion of its own.

The two super-powers met for the first and only time in 751, at Talas near Dzhambul in present-day Soviet Kazakstan, in a battle to determine which of the two civilizations - Muslim or Chinese - would dominate Central Asia. The clash at Talas lasted five days, with the two titans attacking, retreating, reforming and attacking again inconclusively, until finally, joined by the mounted bowmen of the Qarluq Turks, the Muslim Arabs won the day.

Chinese chronicles say the Turks treacherously changed sides in the midst of the action, attacking them from the rear; Arab historians claim the Turks had been secretly allied with them all along, and that the attack from behind was part of a carefully prearranged battle plan.

Whatever the case, the Chinese army broke and fled, leaving the Mulims to rule Central Asia for the next 200 years, and bestowing upon the region the Muslim religion and the Arabic script, both of which have flourished there almost ever since.

The battle of Talas was not only a political and military landmark; it had important technological consequences, too. Chinese prisoners captured at Talas and taken to Samarkand taught the Arabs in turn transmitted to the West.

|

| Overleaf: Profusely patterened with floral, geometric and calligraphic designs, the Chaukundi Toms are among the finest examples of medieval Muslim stone carving on the subcontinent, and particularly beautiful at dawn. |

In 763, the Abbasids founded Baghdad on the banks of the Tigris as the new center of the Muslim empire, ushering in what is known in the West as the "golden age" of Islam, because of its cultural and especially scholarly achievements. This was the era of the Bayt al-Hikmah, the House of Wisdom, an early version of today's think-tanks, from which came translations of Greek mathematical and scientific papers, breakthroughs in geometry and, eventually, discoveries in everything from medicine to hydrology, most of which knowledge was eventually transmitted to the West.

A circular city with four gates, Baghdad was intended to express by its physical form the unity of Islam. This unity, however, did not last. With the seizure of temporal power by the Buwayhids in Baghdad in 936, the Abbasid caliphs were largely restricted to their religious functions. Rival caliphates were established in Cairo and Cordoba, Spain, and the Islamic world fragmented into local dynastic entities whose acknowledgement of Abbasid suzerainty was often only nominal.

But although it lost its original political unity, the Muslim world retained a great degree of cultural unity - largely through faith, but also, in some measure, through the Arabic language, which by the ninth century had become the language of international scholarship and was developing a distinctive and well-elaborated literature of its own.

Translations from Greek, including Aristotle, Hippocrates, Galen and Ptolemy, were accelerated, and important new works in Arabic in mathematics, science and the humanities were produced. A plethora of astronomical tables and geographic route books appeared, and the first version of The Thousand and One Nights, a vivid though largely fictional description of the Baghdad court in the reign of Harun al-Rashid, was compiled.

Among the foremost Muslim thinkers were the geographer and historian al-Mas'udi; the annalist and exegete al-Tabari; the physician Ibn Sina (known in the West as Avicenna), whose works are still studied in medical circles; and al-Biruni, who searched into every branch of human knowledge, anticipating the principles of modern geology, investigating the relative speeds of sound and light, and - 600 years before Galileo - discussing the possibility the earth rotated on its own axis.

This Muslim cultural progress, expressed chiefly in Arabic, far outstripped all contemporary rivals, while the brilliantly intellectual and cosmopolitan courts of the Islamic rulers outshone those of all their non-Muslim rivals.

Also, although the Islamic state declined as a religious entity, Islam itself continued to expand as a religious force - partly as result of conquests by non-Arab Muslims, and partly because of missionary activity by Arab traders and preachers.

Islam was, from the outset, a proselytizing but tolerant religion. The Prophet Muhammad himself respected Judaism and Christianity, whose prophets from Abraham to Jesus he regarded as his precursors, and under the Umayyad caliphs Jews and Christians were left alone to practice their own beliefs. With some rare exceptions, Muslims adhered to the principles of religious tolerance -witness, for example, the large non-Muslim communities found today in areas such as India where Muslims ruled for several centuries.

Soon after Muhammad ibn al-Qasim's conquest of Sind, Muslim preachers and sufis traveled to the subcontinent to invite the local Hindu population to Islam. The first sufis - the word is derived from safa, meaning purity - were wandering ascetics who preached love, peace and brotherhood. Many were scholars or poets who attracted large followings to their gentle view of Islam.

Islam abhors worship of any but God, admits no intermediaries between the individual Muslim and God, and militates against the veneration of saints in any form - yet the places where certain revered sufis lived and died nonetheless became centers of visitation, and today still attract thousands of sincere, if religiously ignorant, believers. They hope that prayer at these sites will be answered by God with the granting of some favor, such as health, fertility or success.

|

| A family takes a camel ride at dusk along Karachi's popular Clifton Beach. |

|

| The tomb in Lahore of Data Ganu Bakhsh, one of the many sufis who brought Islam to Asia by peaceful means. |

The tomb of Abdullah Shah Ghazi, a ninth-century sufi who claimed direct descent from the Prophet and is thought of by his followers as something like the patron saint of Karachi, is; typical of such sites all over Pakistan.

Perched on a hilltop overlooking Karachi's popular Clifton Beach, its tall square chamber and green-and-white striped dome A C decorated with flags and bunting, Abdullah Shah Ghazi's tomb attracts a steady stream of devotees who shuffle forward to caress the silver railing around the burial place and drape it with garlands of flowers.

The Muslims ruled Sind for over 150 years, leaving behind, through the introduction of Islam, a legacy of equity and fraternity which radically changed the lives of the local population, riven by the caste system imposed earlier by the Brahmanical Hindu elite.

Similarly, although the Arabs stayed in Central Asia for only two centuries, they left an indelible imprint on the region south of the Aral Sea. During the eighth and ninth centuries the teachings of the Prophet rapidly superseded other religions, and Islamic tradition and practice took firm root. By the 10th century, Buddhism, Manicheism and Zoroas-trianism had virtually ceased to exist in Central Asia, and Islam had become the predominant religion of the vast region.

Even today, despite decades of religious repression under Communist rule as part of the Soviet Union, six newly independent Central Asian states - Azerbaijan, Kazakstan, Kirgizia, Tajikstan, Turk-menia and Uzbekistan - are still consciously and conscientiously Muslim. In fact, as photographer Francesco Venturi and I followed Islam's path east across these Muslim republics, we found the Islamic faith rapidly reviving under independent political leadership. In Samarkand, for instance, there were 23 functioning mosques compared with only three that had existed two years before, while in Bukhara the Mir-i-Arab Madrasa, or religious college, had received permission to more than double the size of its student body.

Politically and economically, too, the Muslim states of Central Asia, like other former subject nationalities of the Soviet Union, are working to regain control of their own destinies, forging new links with each other and with other nations -most prominently Turkey - to replace ties to Moscow that are now less useful or desirable.

The first independent Muslim state in Central Asia, that of the Samanids, emerged in the ninth century. Its capital was at Bukhara, which under Samanid rule become the showplace of Central Asia, and, thanks to its strategic position astride the Silk Roads, became one of great commercial and cultural centers of the Muslim world.

The Samanid state stretched from Herat in Afghanistan to Isfahan in Iran; the court languages were Arabic, Persian and Turkish; and, at a time when manuscripts were "published" only by tedious hand-copying, it had several privately-owned libraries that were open to the public.

Although all trace of these libraries is now obliterated, one outstanding relic of the Samanid reign remains: the dynasty's 10th-century tomb of decorative brickwork. Small and strikingly simple - a cubical building with inset corner columns supporting a squat dome – the mausoleum is regarded as one of the finest examples of early medieval architecture. By laying the mud bricks with which it was built at different angles, 10th-century craftsmen covered the building with intricate geometric patterns, and established architectural conventions - including that of a dome set on a wedge-shaped drum - which were followed in Central Asia for five centuries.

Buried for hundreds of years, the tomb of the Samanids was rediscovered in 1930 during landscaping of the Kirov Park of Rest and Culture, and was restored using bricks made of clay bound with egg yoke and camel's milk, to match the originals.

|

| A soldier of the legendary Khyber Rifles. |

Islam's Central Asian domain fluctuated violently, alternately extended by conquest and conversion or contracted by nomadic invasion, as the riches of the Silk Roads brought wave after wave of Turkic and Mongol invaders from the Eurasian steppes to the plains of Central Asia, where each encountered and eventually adopted Islam. In the course of their drive for empire, the Mongols came into contact with three religions and their associated cultures -Islam, Buddhism and Christianity. Their attitude toward all three was ambivalent; they professed an ancestral shamanism of their own, embodied in the yasa, or law, of Genghis Khan, but felt the powerful attraction of the new creeds, which seemed invariably to be associated with higher cultures.

Islam at first seemed unfavorably placed. Baghdad was captured and sacked by the Mongols and the Abbasid Caliphate, which had lasted five centuries, was extinguished in 1258. But the Islamic faith slowly established its ascendancy over the conquerors and a powerful revival began. The Golden Horde of the Volga, and the Il-Khan Mongols in Persia, became Muslim, followed somewhat later by the Chaghatai Khans of Central Asia.

Although they stubbornly preserved many strong traditions of their pre-Islamic past, most of the Turkic peoples embraced Islam during the 11th and 12th centuries. Indeed, the Turks of Central Asia came to be among the faith's main champions.

Under the banner of Islam, the Seljuq Turks swept west into Asia Minor, which makes up most of today's Turkey, where, in 1453, their successors, the Ottomans, conquered Constantinople and finally extinguished Islam's old adversary, Byzantium. Successive waves of other Central Asian Turks poured southeast through the Khyber Pass and across the Indus and Ganges plains, making Islam the dominant religion of Pakistan and northern India.

The first of these Turkic invaders were the Ghaz-navids, who, in 1008, defeated a confederacy of Hindu rulers at Peshawar, annexed the Punjab, and extended Muslim influence as far south as Lahore.

|

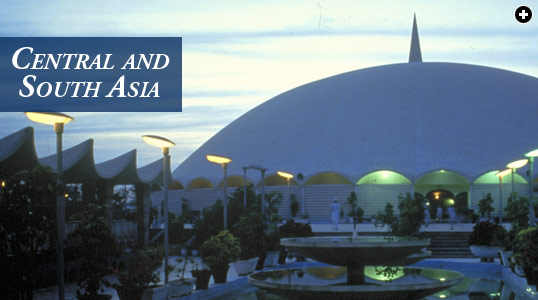

| Emperor Aurangzeb's Badshahi Mosque, with its simple lines and pleasing proportions, is an examples of the best of Moghul architecture. |

Then came the Ghurid conquests which, by the end of the 11th century, had expanded Muslim rule over most of northern India, adding Delhi and Ajmer to the Islamic realm in 1192., and two years later Bihar and Bengal.

In 1206 Qutb al-Din Aybak became the first Sultan of Delhi, founding an Islamic state which gradually brought the greater part of the south Asian subcontinent under its sway, and making the city one of the jewels of Islam. The Delhi sultanate expanded and contracted greatly, depending on the strength and abilities of its ruling dynasty. In 1297 the Khaljid Dynasty pushed its borders southeast into Gujarat and, in 1310, conquered Madura - extending the boundaries of the sultanate to the subcontinent's southeastern coast. The Tughluq Dynasty continued to rule almost all of India until revolts in 1339 cost them Bengal and the south, and struggles between nobles and princes further weakened the sultanate.

|

| India's largest mosque, Jami'Masjid, towers above the crowded streets of Delhi, Muslim capital of India between the 12th and 19th centuries. The modern capital, 20th-century New Delhi, is open and spacious. |

|

| The minarets of Akhora Khattah mosque, on the Great Trunk Road between Pshawar and Islamabad, exemplify the Indo-Islamic style. |

Fate did not stay its hand for long. In 1398 the famous Muslim warrior Timur the Lame (Tamerlane) stormed through the Khyber Pass, devastated Sind and Punjab and sacked Delhi. Timur did not try to maintain control of these vanquished lands -his empire already stretched from the Great Wall of China to the Black Sea - but returned instead to his capital, Samarkand. There, with the loot from his Indian conquests, and using 95 Indian elephants to drag materials into place, he built Central Asia's most magnificent mosque.

The enormous star-spangled portal and colossal blue dome of Timur's tile-covered mosque - named after his favorite wife, Bibi Khanum - prompted one chronicler to write, "Ifc dome would have been unique had it not been for the heavens, and unique would have been its portal had it not been for the Milky Way." And although time and history have been merciless - an avaricious Uzbek amir melted down its metal gates to make coins, and a Russian cannon shell shattered its enameled dome - the mosque's gauntly beautiful ruins still dominate Samarkand's skyline, and are slowly being restored.

From Samarkand, Venturi and I had followed the route of the Muslim armies south to the Afghan border, where, at Shahrisabz, near Timur's birthplace, stand the ruins of the crippled king's White Palace. All that remains are two giant fragments of what was the largest man-made arch of its time: 50 meters (165 feet) high, with a span of 22 meters (74 feet). But even in decay, the tiles adorning the ruined palace portal are a tribute to 15th-century ceramists. Their luster has outlived the empires of Timur's Central Asian successors, the Uzbeks and the czars, and even though, when we were there, Lenin struck a defiant pose in bronze in the adjacent square, it has now managed to outlive Communism too.

It was impossible then to cross Afghanistan because of the civil war there, but several months later, having circumnavigated that country, Wheeler and I reached the Khyber Pass, throughout history Central Asia's main gateway to the subcontinent, and again picked up Islam's path east.

A young soldier with an aging rifle, who was fortunately not called upon to protect us from the Kalashnlkov-carrying Pathans who control the semi-autonomous Tribal Areas of northwest Pakistan, escorted us through the Khyber Pass, which in places narrows to as little as 16 meters (52 feet). From the headquarters of the colorful Khyber Rifles, near the head of the pass, the road first snakes through craggy canyons beneath armor-plated watchtowers manned by Pakistan's Frontier Force. It then descends in wide sweeps,

|

| Pathan mountain men in rolled felt caps and woollen shawls shop for produce from the Punjab plains in the Peshawar bazaar. |

|

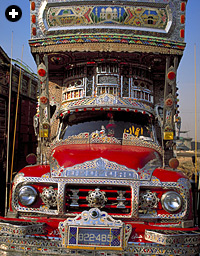

| A gaudy goliath of the Great Trunk Road features, amoung other decorations, a painting of the Ka'bah at Makkah above the driver's cab. |

past fortified Pathan compounds with high mud brick walls, menacing gun turrets and massive iron gates, to the Punjab plain below.

Meter for meter, this is possibly the world's most heavily defended stretch of road.

A sign near the foot of the Khyber Pass proclaims, "Anybody who was ever anybody passed this way." Among the "anybodies" was Rudyard Kipling, who wrote, "The snowbound trade of the north comes down to the market square of Peshawar town." It still does. And although, when we arrived, Peshawar's market square, Chowk Yadgar, was being torn up to build an underground parking garage, Peshawar's bazaars are still among the most exotic in Asia. Here, from shoe-box-sized shops, carts and stalls squeezed into a maze of alleys, all manner of merchandise is bought and sold - from elaborately constructed bouquets of bank notes for newly-weds to bullet-studded bandoliers and Stinger missiles. Now, as always, Peshawar is very much a frontier town, where turbaned Punjabi farmers from the plains rub shoulders with Pathans from the hills in rolled felt caps.

Traffic on the Great Trunk Road south to Rawalpindi and Lahore cannot be said to be organized, but the trucks and buses that bore down on us three abreast were colorful, covered as they were from bumper to bumper with paintings of Muslim shrines, landscapes and wildlife, intricate patterns and portraits of film stars and politicians.

Leaving the traffic and its unique art at Pakistan's purpose-built capital, Islamabad, Wheeler and I skimmed by propeller plane over a sea of snowy peaks, stretching range after range as far as the eye could see, to Gilgit, near Pakistan's border with China. We then jeeped into the lovely Hunza Valley, set amid the gleaming glaciers of the Karakorum Range.

Said to be the model for James Hilton's fictional Shangri-La, Hunza has no written history - mostly songs and tales of brave battles and great polo matches. Polo, in fact, originated in the region and was brought to the West by the British, who also played their own "great game" - espionage - with the Russians in these mountains.

How Islam reached here is not well documented, but it was probably Hunza's economic and strategic value astride the Silk Road from China to India which led to Pathan invasions in the eighth, ninth and 13th centuries before their Muslim forces finally captured the valley and made it possibly the world's highest outpost of Islam.

|

| Delhi's green lungs, the Lodi Gardens are landscaped around the tombs of the Lodi Dynasty, which ruled Muslim India from the warrior-king Timur's incursion, in 1398, until the invasion of his grandson Babur, founder of the Moghul Empire, in 1526. |

|

| Dating from the onset of Muslim rule in India in 1193, the massic Qutb minaret and the Quwwat al-Islam, or Might of Islam, mosque are symbols both of Muslim victory and of the fruitful interaction of Islamic and Hindu architectural styles. |

It was also the Pathans who, in 1313, introduced Islam to Kashmir, in the neighboring Himalayan range, although it was not until the late 14th century that the Delhi Sultan Sikander - commonly called But-shikan, or idol-breaker - made it a predominantly Muslim state. And it was the Pathans too, who restored order to Muslim India after Timur withdrew, leaving it in anarchy. The Pathan Lodi Dynasty ruled from Delhi until 1526.

It was at this stage that Babur, founder of India's most celebrated Muslim dynasty, the Moghuls, marched through the Khy-ber Pass. A descendant of Timur on his father's side and of Genghis Khan on his mother's, and a self-described "itinerant emperor," Babur became ruler of the Central Asian principality of Ferghana at age 11, and conquered Samarkand at 14. He then lost both and went off to Afghanistan, where he seized Kabul. Finally he invaded India, defeating Ibrahim Lodi, the last Sultan of Delhi, and established his own capital there.

Employing Hindu artisans, the early sultans had built mosques, palaces and elaborate mausoleums in Delhi, best evidenced by the Quwwat al-Islam mosque and the large, domed Lodi tombs. The earliest extant mosque in India, the Quwwat al-Islam stands at the foot of the mighty Qutb minaret, started by Qutb al-Din Aybak in 1193, after he defeated the last Hindu kingdom of Delhi, and completed by his successors. The mosque's rectangular courtyard is enclosed by cloisters lined with carved stone columns, and although a massive screen of five lofty arches gives the front of the prayer hall an Islamic flavor, the carved calligraphic inscriptions betray the hands of Hindu craftsmen in their naturalistic, curving lines.

|

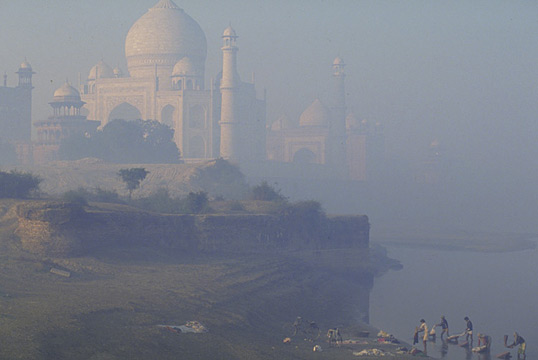

| The Taj Mahal. |

Under the sultans of Delhi, Muslims and Hindus had deeply influenced each other's way of life: Turkic and Pathan dynasties adopted Indian-style dress, while Hindu intellectuals were introduced to Persian literature. Nonetheless, it was interaction between India and Islam under the Moghuls which produced the most creative encounter between the two cultures. By blending elements from Persia and India, the Moghuls created one of the most sophisticated civilizations in history, and fashioned a new, distinctive Indo-Islamic architectural style epitomized by the Taj Mahal.

|

| Living in the shadow of the opulent past, Agra's poor wash their clothes in the yamuna River below the Taj Mahal, and eke out a living farming nearby land. |

Babur's son Humayun was more of an intellectual than a statesman. He spent most of his life in exile in Persia and, shortly after regaining the Delhi throne in 1536, died in a fall down his library stairs. He did, however, introduce the art of miniature painting into the Moghul court, where it reached an excellence which has rarely been surpassed.

The real establishment of Moghul rule over India was the achievement of Babur's grandson Akbar, called "the Great." His empire stretched from Afghanistan to central India, and from Sind to Kashmir. Akbar built Fatehpur Sikri, near Agra, as his capital, but, despite the splendor of the imperial city, abandoned it after 14 years - some say because of lack of water, others because of troubles in the north. Akbar did, in fact, move north to Lahore, now in Pakistan, where he built the solid sandstone citadel of Lahore Fort.

Akbar's pleasure-loving son Jehangir built a beautiful palace within the fort's walls, and his extravagant grandson Shah Jahan added the famed Naulakha Pavilion, made of marble studded with semi-precious stones. Aurangzeb, the last and most pious of the great Moghul rulers, built the massive Alamgiri Gate and, opposite it, the enormous Bad-shahi Mosque, large enough for a congregation of 66,000.

|

| Children leaving a Qur'an class file across the courtyard of Dargah Mosque, built by the Moghul emperor Akbar at his short-lived capital of Fatehpur Sikri. |

Moghul art and architecture reached its height in the 17th century under Jehangir, who laid out the Shalimar Gardens in Kashmir, and later under Shah Jahan, during whose reign (1627-1658) some of the most vivid reminders of Moghul glory were constructed, including the Red Fort at Delhi and, at Agra, the Taj Mahal. Indeed, some say that it was Shah Jahan's passion for building that led to his downfall and that his son, Aurangzeb, deposed his father in part to put a halt to his architectural extravagances, which were bankrupting the empire.

In fact, the Taj Mahal's unerring symmetry and perfectly proportioned lines may be sublime, but the marble mausoleum that Shah Jahan built for his queen, Mumtaz Mahal, was indeed an extravagance. Spotless white marble was brought from Makrana, precious and semiprecious stones were collected from within and without the empire, and the legendary imperial coffers never ceased pouring forth money as more than 20,000 architects, craftsmen and laborers toiled for 22 years to complete the mausoleum, whose doors were of silver and vaults lined with gold.

Such opulence seems even more extravagant when measured against the grinding poverty prevalent throughout India today. And although some people argue it is best seen under a full moon, arid others insist it is more sensuous by sunset, my own most lasting impression of the Taj Mahal is at dawn, when it looms out of the mist over the Yamuna River and over the paupers of Agra washing their clothes in the filthy river water.

From Agra, Wheeler and I drove along roads clogged with bicycle rickshaws and buffalo carts -with the occasional dancing bear among the pedestrian traffic - to the former imperial city of Fatehpur Sikri, whose red sandstone palaces and audience halls remain almost as perfectly preserved today as when Akbar abandoned them over 400 years ago.

|

| Rising from the eerie, boulder-stren landscape of the Deccan, Golconda fortress, near Hyderabad, was the capital of the Qutb Shahis - a dynasty of Muslim poet-sultans that ruled southern India in the 16th century. |

Our journey along Islam's path east next took us to the medieval citadel of Jaisalmer, near where Akbar was born as his parents fled into exile across the Thar Desert, and in Akbar's footsteps across Rajasthan to one of India's most renowned mausoleums: the tomb of the 14th-century Muslim cleric Khwaja Muin al-Din Chisthti, at Ajmer. Akbar used to travel to Ajmer every year from Agra, and Chisthti's marble-domed tomb, which stands in the heart of the old city surrounded by shops selling floral wreaths and other offerings, still attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors a year.

|

| Hyderabad's Makkah Mosque took nearly 60 years to build. Begun in 1618 by the Qutb Shahis, it was not finished until 1687, by which time the Moghuls had annexed the Golconda kingdom. |

Our next destination was another popular, and unusual, site: the offshore mosque and tomb of Hajji Ali, who drowned in Bombay harbor. The buildings are reached by a long causeway which can only be crossed at low tide. It is lined with beggars, and since the giving of alms is one of the five pillars of Islam, the visitors are an easy touch.

South of Bombay lies India's central plateau, the Deccan, which for centuries was an arenaof Hindu-Muslim power struggles. Even today the region's capital, Hyderabad, with its almost equally divided population of Muslims and Hindus, is frequently the scene of intercommunal strife; during our visit, for example, a dusk-to-dawn curfew was in force in parts of the city following sectarian violence.

|

| Hyberabad's Makkah Mosque took nearly 60 years to build. Begun in 1618 by the Qutb Shahis, it was not finished until 1687, by which time the Moghuls had annexed the Golconda kingdom. |

|

| Young girls from a Muslim village near Jaisalmer, in the Thar Desert, wear distinctive tonsures. |

Islam reached this far south in the 14th century, and Hyderabad's most famous Muslim monument, the Char Minar - a triumphal arch in the heart of the old city, surrounded by lively bazaars - dates from that period. The most impressive monument to medieval Muslim rule in the Deccan, however, is 11 kilometers (seven miles) from Hyderabad: Golconda, one of the largest fortress ruins in the world.

Protected by the ramparts of Golconda, and enriched by nearby mines that produced such world-famous diamonds as the Orloff and the Koh-i-noor, the Turkoman Qutb Shahi Dynasty ruled over part of the Deccan for a century and a half. Their wealth and liberality, however, attracted the unwelcome attention of Delhi, and in 1687 the devout Moghul emperor Aurangzeb, accusing them of "lack of piety," appeared with his armies at Golconda's gates.

From the fastness of their citadel atop Golconda's granite hill, ringed by battlemented walls, the Qutb Shahis held out for seven months before losing the fort through treachery: One of the defenders was bribed to leave a gate open at night. Ironically, however, their defeat also signaled the beginning of the long decline of the Moghul Empire itself. Finally, in 1858, the last of tne Moghuls, by then bereft of any real power, was deposed by the British.

Some nine decades later, when the British withdrawal from India became inevitable, intercom-munal strife posed the central, and most painful, political issue to be faced by both the departing empire and the newly independent state to be born. The optimum proposal from the Muslim point of view — partition — proved to be the only one that could be adopted. Thus, in 1947, Pakistan became an independent nation with a population that was 90 percent Muslim. Today, Pakistan has the second largest Muslim population, after Indonesia, in the world.

And India has the third.

|

Aramco World contributing editor John Lawton has eight other complete issues of the magazine to his credit, the first published in 1977. He is also the author of Samarkand and Mukhara, published in London by Tauris Parke Books. |