Written by Christopher Walker

Photographed by Thorne Anderson

|

Detail of a portrait of Alexander

Hamilton by John Trumbull(1806). |

| NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY / SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION / ART RESOURCE |

Of all the confederacies of antiquity,

which history has handed down to us,

the Lycian and Achaean leagues,

as far as there remain vestiges of them, …

were … those which have best deserved,

and have most liberally received,

the applauding suffrages of political writers.

—Alexander Hamilton,

Federalist No. 16

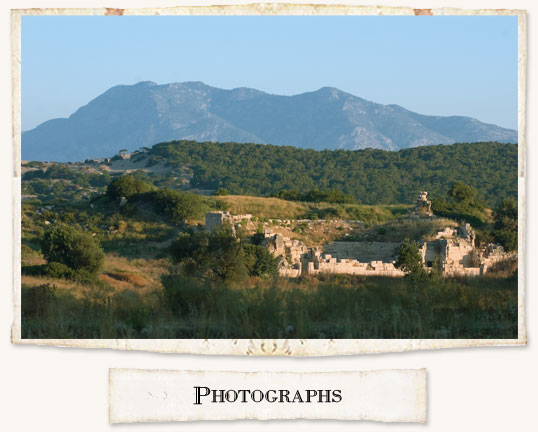

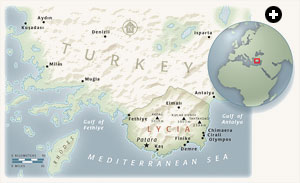

with their picturesque covering of pine and juniper forest, and overlooking Turkey’s “Turquoise Coast,” a long-silent bouleuterion, or council chamber, once held the proceedings of the Lycian League, considered to be history’s earliest example of the republican form of government. With its rows of stone seats set out in a semicircle around a raised dais, it looks uncannily like the chambers of modern legislatures and parliaments.

|

The historical significance of the Lycian League was its uniquely federal character. Whereas other “leagues” and alliances in the Hellenistic world were often simpler bands of city-states united against common foes, the Lycians of southwestern Anatolia shared a racial and cultural lineage that helped set them apart from other proto-nations of the Mediterranean world.

Until the American model was forged half a world away and nearly 2000 years later, no other legislative body had apparently considered the Lycian example. The senate of Rome was a unicameral oligarchy, made up of those who were rich, noble and old enough to qualify. Britain’s parliament, although bicameral and representative in many ways, was not developed according to

a federal model.

At one time, the Lycian bouleuterion housed the elected representatives of the 23 city-states that first came together in approximately 205 BC and formally confederated in 168 BC. The resulting League not only kept its often squabbling members united, but also managed to exert authority over individual citizens of

its constituent states.

|

The world’s first recorded example of representative democracy had its capital in the port city of Patara, first mentioned by the Greek historian Herodotus, who described it as

the cult center of the god Apollo.

Both Horace and Virgil gave the city greater importance, referring to Patara (rather than Delos) as Apollo’s birthplace.

The Lycians, according to their most respected modern chronicler, the British archeologist Geoffrey Bean, “among the various races of Anatolia, always held a distinctive place. Locked away in their mountainous country, they had a fierce love of freedom and independence, and resisted strongly all attempts at outside domination; they were the last in Asia Minor to be incorporated as a province in the Roman Empire.”

The Lycians had their own language and alphabet, although following the conquests of Alexander in the fourth century BC, those gradually gave way to Greek. Historians have likened them to the Swiss today: a hard-working and prosperous people,

neutral in international affairs but fierce in their defense of freedom and conservative in their attachment to ancestral tradition.

The Lycian League flourished both in the Hellenistic period, when the harbor was used as a naval base by Alexander’s successors, and during the Roman Empire, when, against the odds,

Lycia continued to function as a

largely autonomous province.

In that turbulent period, the

parliament building was joined by such impressive monuments as the amphitheater, the ornate city gate, baths, temples, a lighthouse—now claimed as the world’s oldest—and a huge granary dedicated to the Emperor Hadrian, who in the year 131 visited with his wife Sabina. Before that,

Lycia had been a stopping-off point for St. Paul during his missionary journey from Rhodes to the Phoenician port of Tyre. Patara’s influence began to wane in the seventh century, after the Arab conquest, by which time its harbor had become almost totally silted up. By the 15th century it was entirely abandoned.

he city remains in

that condition today,

although the swarms

of mosquitoes that molest archeologists and tourists alike on its spectacular 18-kilometer (11-mi) sandy beach are no longer malarial. The remote spot provides nesting places for the endangered hammerhead turtle and is home to legions of snakes and scorpions. It features swampy terrain and rampant vegetation, which strict Turkish conservation laws will not permit the use of pesticides to combat, partly explaining why the 100-hectare (250-acre) archeological site remained largely neglected until the late 1980’s.

he city remains in

that condition today,

although the swarms

of mosquitoes that molest archeologists and tourists alike on its spectacular 18-kilometer (11-mi) sandy beach are no longer malarial. The remote spot provides nesting places for the endangered hammerhead turtle and is home to legions of snakes and scorpions. It features swampy terrain and rampant vegetation, which strict Turkish conservation laws will not permit the use of pesticides to combat, partly explaining why the 100-hectare (250-acre) archeological site remained largely neglected until the late 1980’s.

“When we first started digging, our tents were burned down by angry local people, who were convinced that we were responsible for the government restrictions that prevented them from building any type of tourist infrastructure,” says Gül Işin, an archeologist with Akdeniz University and a leading member of the joint Turkish–German excavating team.

Although the Patara ruins were buried under thousands of tons of windblown sand at the time that the US Congress came into being

in the late 18th century, the once unique elected-representative

system practiced by the Lycian League for at least 300 years was

a formative influence on the framing of the US Constitution.

It was the structure of the

central Lycian authority and the responsibilities it was given that made it attractive to the framers of the US Constitution. The Lycian model provided a formula that permitted the framers to compromise the interstate rivalries that endure to this day: Whereas the “upper house” would be made up of an equal number of senators from each state, the “lower house” would be made up of representatives elected in proportion

to each state’s population. In addition, the Lycian executive was not hereditary: The Lycian League was headed

by an annually elected president known as the lyciarch—and, intriguingly, possibly also the lyciarchissa.

Sitting in the lyciarch’s throne-like seat today, it is possible to imagine the representatives of the League sitting

in the 13 semicircular rows of seats, holding debates on military and political affairs, making and breaking legislative alliances, in much the modern way.

“Among classical federations, its structure was unique,” says Işin. “Of course, there are design differences between this building and the American House of Representatives, which was discussed and founded when this was hidden under the sand.” But the federation is mentioned three times

in the Federalist Papers, the series

of 85 seminal essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison in 1787 and 1788,

the years when ratification of the US Constitution was being debated.

What particularly caught the eye

of political commentators, stretching back to the Roman geographer and man of letters Strabo, was the way

the League devised its system of proportional representation to distribute power among its differently sized members. According to Strabo, the member cities sent one, two or three representatives to the assembly, with the six largest members (including the capital, Patara), having the right to

the maximum three votes.

According to James W. Muller, a constitutional scholar and professor

of political science at the University of Alaska, the Lycian confederacy made three contributions to the US Constitution. First, he says, “it was a model of

a federal union the strength of whose parts in the national councils was proportionate to their size. Second, it showed the possibility of popular government that was representative. Thirdly, it offered the example of a strong national government with its own strong officers and the power to make laws that applied directly to individual citizens.”

Explaining the global influence of

the League, he adds that, since 1787, “the American Constitution has drawn the attention of constitution-makers,

not the Lycian League. Before that,

I am not aware of other governments

that hearkened to the example of Lycia in drawing up constitutions.”

Muller, who first visited Patara three years before the excavations began to reveal what lay under the thousands

of truckloads of sand that have since been removed, is also an admirer of the 18th-century French political philosopher Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu. Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws was the most popular political book in America in the 1780’s.

Observing that in Federalist No. 45, James Madison qualified his reference to the Lycian confederacy by explaining that it provided an example “as far as its principles and form are transmitted,” Muller added, “There were limits to the knowledge of Madison, Hamilton, Montesquieu and Strabo about how the Lycian confederacy actually worked. But those limits are being rectified by the current excavation in Patara. We are much indebted to the painstaking work there, which is deepening our understanding of the antecedents of the American Constitution.”

“The celebrated Montesquieu,” as Madison described him in 1787, was a French philosopher admired by people on all political sides of the Constitutional Convention. (“S’il falloit donner un modèle d’une belle république fédérative,” he said, “je prendrois la république de Lycie.” “If one had to propose a model of

an excellent federal republic, I would choose the republic of Lycia.”) It was this remark that directed so much attention to the political arrangements of the people who had lived in 23 city-states along the southern coast of Turkey during the last two centuries BC.

t the foot of the evocatively

preserved bouleuterion,

where visitors can wander and climb to their hearts’ content

during opening hours, there is a room archeologists believe once housed the archives of the League. In keeping with the theme of Apollo that dominates the Patara ruins, on the room’s entrance stone are carved the three symbols of the god: a baby turtle,

a lizard and a grasshopper.

t the foot of the evocatively

preserved bouleuterion,

where visitors can wander and climb to their hearts’ content

during opening hours, there is a room archeologists believe once housed the archives of the League. In keeping with the theme of Apollo that dominates the Patara ruins, on the room’s entrance stone are carved the three symbols of the god: a baby turtle,

a lizard and a grasshopper.

On the other side of the outer wall lie hundreds of large, recently numbered stones among a whispering carpet of daisy-like yellow and white camomile flowers. When more funds have been raised for the excavation work, the stones will be put into their original positions as part of an ambitious

historical reconstruction.

“The different political weights of cities in the common assembly of the Lycian confederacy showed the possibility of a federation in which members of different sizes came together in a way which reflected their real strength,” Muller explains.

“This was the idea for Congress in James Madison’s Virginia Plan, which proposed a bicameral legislature—two houses—both of which gave the states representation in proportion to their population, as in Lycia. Madison then had to compromise with his opponents and accept the equality of states in

the Senate, but the American House

of Representatives, where states have representation in proportion to their population, is founded, as Madison urged, on the principle of the Lycian confederation.”

The framers had more to say than this, too. In Federalist No. 9, Hamilton explained that in Lycia, the common council had the power to appoint all judges and magistrates for the confederated cities. In Federalist No. 16, he pointed out that in Lycia, federal laws applied not only to cities, but

also directly to individuals. In Federalist No. 45, Madison referred specifically to the “degree and species of power” of the national government in Lycia, which he welcomed as the model for the stronger national government established in the Constitution.

Although the largely unspoiled site

of present-day Patara provides insight into the setting where Lycians lived and governed, there are as yet few clues about much else—for example, how they lived, and how they looked

—beyond the hints on some reliefs and coins that they wore their hair long.

Herodotus claimed that the Lycians had a different appearance from other troops in Asia Minor, who commonly wore Greek armor. As the earliest author to ever mention Patara, he wrote this description of a Lycian naval crew in 480 BC, as they joined Persian King Xerxes’ invasion of Greece with 50 ships: “They wore greaves (shin protectors) and corselets (body armor); they carried bows of cornel wood, cane arrows without feathers, and javelins. They had goatskin slung around their shoulders, and hats stuck round with feathers. They also carried daggers and rip-hooks.”

One of the most fascinating finds at the site is the “Stadiasmus Patarensis,”

a monument that shows firsthand and in detail how the Lycian League grew, giving the names and distances of member cities—just as a sign in Los Angeles today might read “Las Vegas: 237 miles, Boise: 682 miles, Spokane: 944 miles; San Francisco: 354 miles.” One of the inscriptions states that the Lycians were “the friends of the Romans” and another that “a consultative parliament was established by the best men of Lycia.” The monument consisted of 53 large inscribed stones, of which 41 have been found; finding the rest and rebuilding the structure will have

to wait for more funding.

In the ruins of Patara, archeologists have also

found hints of the power and influence of at least certain Lycian women. Inscriptions found in the remains of the bouleuterion show that at least two women, named Marcia Aurelia and Crision Nemeso, were using the title lyciarchissa. But there is as yet no proof whether they were actually elected in their own right to run the assembly or whether they were using the feminine of lyciarch because that was their husbands’ title.

“Nothing uncovered so far can yet solve this fascinating mystery one

way or the other,” says Işin. “We

are hoping that something not as

yet unearthed will one day be able

to provide an answer.”

However, on the entrance wall to the impressive 10,000-seat amphitheater, whose ruins tower next door to the much smaller bouleuterion, the female name Velia Prokla is clearly carved into the stone, recording that she was the benefactor who put up

the money to construct the building. “Either she was extremely rich in her own right, or it was family money,” Işin explains.

Herodotus had already noted that Lycians have “customs that resemble no one else’s. They use their mother’s name instead of their father’s.” As excavations continue, more than just a prototype for American democracy may yet emerge from the sands of Patara.

|

Christopher Walker, now a London-based free-lance journalist and broadcaster, was Middle East correspondent of The Times of London for 15 years, based in Jerusalem and Cairo. He was also head of The Times’ bureaus in Moscow and Belfast.

He can be reached at [email protected]. |

|

Thorne Anderson (thornephoto@ gmail.com) has covered Europe and the Middle East for numerous newspapers and magazines. His collabo-

rative book, Unembedded: Four Photojournalists on the War in Iraq, was published in 2005 by Chelsea Green. He lives in Amsterdam. |