"That's a

great story!" I thought. "But is that really how it happened?"

Activities

There are no

photographs of Ernest Hamwi. Nor is there any record of his booth or, for that

matter, of his existence in St. Louis. Indeed, says Ellen Thomasson, curatorial

assistant for the Missouri Historical Society, "There were several claims

to the invention of the ice-cream cone at the fair, all made many years after

the fact. As far as we can tell, not one has been definitely proved."

|

| "Come on over! Our ice-cream cones will melt in your mouth!" says 88-year-old Albert Doumar. He should know. He's been making zalabia cones for decades on the same machine his Uncle Abe built in 1905. |

Nor do zalabia hail from the Arabian Gulf region.

Historically, they are Levantine, popular in Syria, Lebanon and parts of Iraq

and Turkey. And they are not made on a waffle iron. Actually, they're flatter

than waffles and most resemble Italian pizzelle. Like the pizzelle, they have a grid pattern on their

surface. There is another, very different, zalabia that is served in North

Africa. It is made of looping, pretzel-like strands of deep-fried batter that are

smothered in honey or syrup and often tinted a garish orange.

But back to

Hamwi and his zalabia. He and his wife, the story goes, took their meager

life's savings and invested them in a zalabia booth at the Louisiana Purchase

Exposition, also called the 1904 World's Fair. The fair covered some 500

hectares (1235 acres) and highlighted recent inventions, including the

airplane, invented the year before; the radio; the telephone switchboard; and

the silent movie. It also housed palaces, halls and pavilions displaying the

wonders and delights of the world. More than 18 million visitors passed through

the Exposition during its seven-month run, and there were also scores of

vendors offering much to eat.

The Hamwis, like

many other immigrants from the Levant, were trying to bring to the US the

crisp, round, cookie-like snack that was so popular back home. The zalabia were

baked between two iron platens (flat metal plates), each about the size of a

dinner plate. The platens were hinged together and held by a handle over a

charcoal fire. Once cooked, the zalabia were sprinkled with sugar and served.

|

| "Quickly does it!" With a twist of the hand, a zalabia is rolled into a cone around a wooden form. Each thin pastry must be shaped while it is hot and pliable. As it cools, it hardens and is ready to hold a scoop of ice cream. |

Ernest Hamwi's

booth was next to one of the some 50 ice-cream stands at the fair. Just who

owned the stand is unclear, but whoever he was, his ice cream sold faster than

Hamwi's zalabia—so fast, in fact, that one day he ran out of clean glass cups.

At that moment, some say, the ice-cream man saw the possibilities of the

zalabia; others claim the zalabia man saw the possibilities of the ice cream.

Hamwi's story

is largely based on a letter he wrote in 1928 to the Ice Cream Trade Journal, long after he had established the

Cornucopia Waffle Company. By the late 1920’s, the ice-cream cone industry in

the US was producing some 250 million cones a year. Despite the lack of detail

in Hamwi's account, cookbooks today generally credit him as the first

ice-cream-cone maker. In fact, the International Association of Ice Cream Manufacturers

recognizes his claim.

There are,

however, other stories. All involve the same setting, characters and plot: a

1904 Exposition ice-cream vendor who runs out of cups and a vendor (Syrian or

Turkish—the terms were roughly interchangeable at the time) who saves the day

with a combination of zalabia and ambition.

One of these

stories is about Abe Doumar.

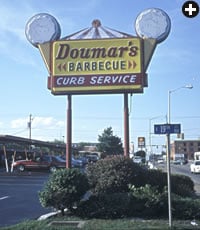

We know more

about Abe Doumar than about Ernest Hamwi, thanks to Abe's nephew Albert, who at

age 88 is the owner of Doumar's Cones and Barbecue in Norfolk, Virginia. Like

Hamwi, Abe Doumar came to the United States from Syria. At age 15 he sailed to

the US on a third-class ticket and soon found work as a souvenir salesman at

fairs around the country. In 1904, he was in his early 20's. At the Exposition,

he sold souvenirs by day and, at night, joined the zalabia salesmen along the

Exposition's entertainment promenade.

|

| "Welcome to Doumar's"―this restaurant has been welcoming visitors to Norfolk, Virginia, ever since Abe Doumar brought his cone-making machine to the Jamestown Exposition there in 1907. |

Abe told Albert

that it was at the fair that he took a zalabia and rolled it into a cone, much

as he had been accustomed to do with round pieces of flatbread in Syria when

making a sandwich. But instead of bread, this was zalabia, and instead of

filling the cone with slices of meat or falafel (fried balls of chickpeas or field beans), he added ice cream to make what he

called "a kind of Syrian ice-cream sandwich." Abe shared the idea

freely among the vendors, he said, and it was in this way that the "invention"

spread from stand to stand. If you travel to the Middle East today, you'll see

street vendors selling cone-shaped flatbread sandwiches that are eaten much

like ice-cream cones.

After the

Exposition, Abe went to North Bergen, New Jersey. There, he developed what he

believed was his invention into a four-iron machine that made zalabia that

could be rolled into cones. In 1905, he opened ice-cream stands at Coney Island

and "Little Coney Island" in North Bergen. Two years later, he left

others to operate them while he moved to Norfolk, Virginia, ahead of the 1907

Jamestown (Virginia) Exposition. As he prospered, he brought his parents and

three brothers to the US from Syria. Today, many family members still reside in

Norfolk, where Doumar's restaurant has become something of a local legend. In

2001, the website Citysearch.com named Doumar's Cones and Barbecue one of the

two best "comfort food" restaurants in Norfolk. Some mornings, Albert

still runs the more than century-old cone machine that cooks each zalabia for

one minute between the cast-iron platens. The zalabia is then removed, rolled

into a cone around a wooden form and allowed to cool and harden until

crispy—all at a speed of some 200 cones per hour.

|

| "It's a great family business, and I'm proud to be part of it," says Thaddeus Doumar. His great-uncle Abe claimed to have suggested the ice-cream cone in 1904. Today, Thaddeus helps manage the family cones and barbecue restaurant in Norfolk, Virginia. |

But Hamwi and

Doumar are not the only contenders for the title of Inventor of the Ice-Cream

Cone. Nick Kabbaz, president of the St. Louis Ice Cream Cone Company, claimed

to have worked for Hamwi years earlier and said that the invention was actually

his idea. David Avayou, a Turkish immigrant who owned ice-cream shops in

Atlantic City, New Jersey, said that he had seen paper ice-cream cones in

France and adapted the idea—but with edible materials—at the 1904 Exposition.

Charles

Menches, the ice-cream vendor who claimed to have worked in the stand next to

Hamwi's, said he was the first to have rolled zalabia cones, and that he made

two of them for a lady friend: one as a container for flowers, and the other

for ice cream.

|

| "Enjoy!" would be the first word Abe Doumar would say if could walk out of the picture and sit with this patron enjoying a zalabia ice-cream cone, just off the machine he invented. |

Finally, there

is Italo Marchiony of New York, who filed a patent for "small pastry cups

with sloping sides" the year before the 1904 Exposition. But the bottoms

of his cups were flat, not conical, and thus his post-Exposition claim that the

cone manufacturers were violating his patent melted under the hot gaze of the

law.

It is, in the

end, something of a toss-up. Alixa Naff, donor and archivist of the

Smithsonian's Naff Arab-American Collection, told The Virginia Post that

"there was no way I could literally refute Mr. Albert Doumar's statement

that his uncle invented the ice-cream cone. ...It is such a simple technique

that it may have occurred to other people at other places at about the same

time. I have accepted Mr. Doumar's statement, keeping in mind, however, that

possibility."

But, no matter

how you roll the zalabia, the

tales of its use as an ice-cream cone are now part of American folklore. Although

the historical accuracy of its invention may be in doubt, the creative

brilliance that joined two ideas from two parts of the world and made from them

a national cooking symbol is not. What could be more American than that?

click here to view the original article

| Jack Marlowe taught English

literature in California and Greece and served as a high-school administrator

in the San Francisco Bay Area and, under Fulbright sponsorship, in India and

Egypt. |

| David Alan

Harvey was National Geographic staff

photographer from 1978—the year he was named Magazine Photographer of the

Year—until 1986. Now a free-lancer, he is a member of the photographic

cooperative Magnum Photos. |

STANDARDS

This lesson correlates to the following national standards for world history and language arts, established by MCREL at http://www.mcrel.org/:

- Understands patterns of immigrant life after 1870 (e.g., where people came from and where they settled; how immigrants formed a new American culture; the challenges, opportunities, and contributions of different immigrant groups; ways in which immigrants learned to live and work in a new country)

- Gathers and uses information for research purposes

- Demonstrates competency in the general skills and strategies of the writing process