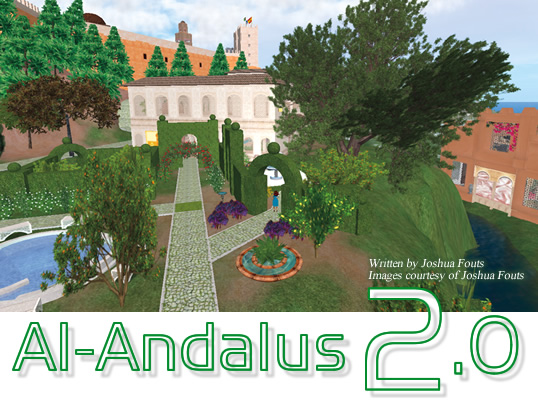

| Down to the details of flowers in bloom and fruiting orange and lemon trees, the gardens in the virtual community of Al-Andalus, below, have been “built” to resemble those of the Generalife in Granada, Spain. |

|

|

| The arch of red roses at the center of the topmost image is one of the contributions of Al-Andalus Project co-founder “Rose Springvale,” above. |

In 2008, my collaborator, Rita J. King, and I embarked on a study titled “Digital Diplomacy: Understanding Islam Through Virtual Worlds” to explore the potential value of on-line, digital environments in cultural dialogue. We spent a year researching communities across four continents in the physical world and throughout a number of on-line virtual worlds. We chose to focus on Second Life not only because it is by far the largest of the on-line virtual worlds but, most importantly, because it is created entirely by its users.

In our study, we learned that the more time that users invest in their Second Life experiences, the more they come to express high degrees of creativity and understanding of each other. In this and other ways, Second Life is more like the physical world than we had anticipated. Similarly, we learned that the commonplace distinction between a virtual experience and a physical experience is too sharply drawn: The virtual, we found, is psychologically quite real. People exchange real emotions and real ideas, experience real interactions. While this is what makes all social media tick, Second Life’s immersive qualities make it a truly new frontier for cultural relations.

|

| Viewed from the west, the walled center of Al-Andalus in Second Life contains, in the foreground, a virtual Alhambra and caliph’s palace and an auditorium. Behind them is La Mezquita (the mosque) with its square minaret, and to its right are residences and the suq, or market. |

|

| The entrance of the caliph’s palace. Since 2007, some 18 people have contributed virtual construction to the community. |

In Second Life (or sl, as users call it), we found dozens of virtual communities amid the several hundred “sim” locations. Among them, one stood out for its commitment to the exploration of cultural dialogue: Its name is Al-Andalus. The community occupies a group of virtual islands, and its virtual architecture and lush gardens are designed to resemble two of the great monuments of medieval Islamic architecture, the Alhambra in Granada and the Great Mosque in Córdoba. The virtual buildings were conceived and built to evoke a historical memory of convivencia, the Spanish term for the harmonious “living together” of Muslims, Christians and Jews in the southern Iberian Peninsula during the Islamic caliphate there.

In the sl community called Al-Andalus, several hundred people—from Singapore, St. Petersburg, Jiddah, London, Houston, and cities and towns across more than a dozen real countries—are beginning to explore what convivencia might mean today. In real life, some of the more active Al-Andalus members are accomplished professionals; they include a Russian ballerina, a Saudi accounting student, a retired British engineer and a Houston attorney.

Al-Andalus was founded in 2007, when a group of seven sl members from the “Confederation of Democratic Sims”—an experiment in the shared ownership and governance of virtual space—met to search for common ground and try to overcome the differences among Muslims, Jews and Christians. This globally dispersed group couldn’t afford to meet in person, let alone set up a real-world social experiment in intentional community. The founders were led by two attorneys, both of whom prefer to use their sl names in that context: “Michel Manen” is a Canadian academic and “Rose Springvale” lives in Houston, Texas. In July 2007 the Al-Andalus group purchased an island in sl, and together they began construction of virtual versions of rooms of the Alhambra palace, its neighboring Generalife gardens, a grand mosque called “La Mezquita” (the Spanish word for “mosque,” originally from the Arabic masjid), and dozens of apartments that they “built” in Muslim, Jewish, and Christian quarters. They added a bazaar for selling virtual goods, from home furnishings to both western and Arab attire. Part history and part fantasy, Al-Andalus is, above all, a metaphor for the future.

Al-Andalus was founded in 2007, when a group of seven sl members from the “Confederation of Democratic Sims”—an experiment in the shared ownership and governance of virtual space—met to search for common ground and try to overcome the differences among Muslims, Jews and Christians. This globally dispersed group couldn’t afford to meet in person, let alone set up a real-world social experiment in intentional community. The founders were led by two attorneys, both of whom prefer to use their sl names in that context: “Michel Manen” is a Canadian academic and “Rose Springvale” lives in Houston, Texas. In July 2007 the Al-Andalus group purchased an island in sl, and together they began construction of virtual versions of rooms of the Alhambra palace, its neighboring Generalife gardens, a grand mosque called “La Mezquita” (the Spanish word for “mosque,” originally from the Arabic masjid), and dozens of apartments that they “built” in Muslim, Jewish, and Christian quarters. They added a bazaar for selling virtual goods, from home furnishings to both western and Arab attire. Part history and part fantasy, Al-Andalus is, above all, a metaphor for the future.

|

| Clothing for sale in the shops in the Al-Andalus suq is sold for Linden dollars in amounts equivalent to one to five us dollars—payable through PayPal to the shop’s owner. |

|

| In a meeting hall in the village of Neufreistadt, which adjoins Al-Andalus in Second Life (sl), members of Al-Andalus join members of other communities to elect a chancellor of the Confederation of Democratic Sims, the governing body of sl’s more than 60 communities. |

In a note that they circulated to all sl residents, the members announced their intention to build “around this virtual space a community of individuals willing to explore the modalities of interaction between different languages, nationalities, religions and cultures within a political and juridical space shaped by authentic Islamic principles. Those principles include political participation, separation of powers, justice and the rule of law. Membership in the community is open to all.”

Three years later, the community is still expanding and, like any human community, is experiencing its growing pains.

To talk about it, Rose Springvale met me in Al-Andalus’s gardens. We walked along a well-groomed gray stone path lined with towering manicured hedges, which opened onto a circular reflecting pool flanked by lemon and orange trees, blue delphiniums, purple wisteria, pink rhododendron, black-eyed susans and climbing red rose bushes trained into arches. (“My contribution to Al-Andalus,” Rose said as we walked.) She invited me to sit on a bench under a giant cypress modeled after an actual tree in the real-world Generalife in Granada.

Down the hill I could see a river and some stucco homes, but—unlike in the real Granada or Córdoba—the backdrop was the ocean that lies beyond what are now actually six Al-Andalus islands. Each is fully occupied and has a waiting list of would-be residents. Each tenant pays rent ranging from l$1100 ($4) to l$7000 ($28) per week—money that covers the approximately $250 monthly sim-maintenance charge that Rose pays to Linden Lab.

In 2008, she explained, her cofounder had to leave sl because of real-world time demands. This left Rose to oversee management of the island, which she described as “a major challenge” for someone who, in the physical world, is an attorney with an international client base, a mother of two and the wife of a ceo husband.

To guide the community’s growth, member “Micael Khandr” hosted conversations among Al-Andalus’s members. They came to an agreement to create a collaborative, representative community government without regard to religion.

In the physical world, Khandr’s name is Michael Carey, and he is a professor of organizational management at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington. For Al-Andalus, he founded the “Convivencia Institute” to focus on promoting understanding among religions. “The earliest Muslim rulers of what was known as Al-Andalus created … convivencia through their liberal interpretation of dhimma, that part of the religious law of Islam that protects the other two ‘Peoples of the Book,’ i.e., Jews and Christians,” he stated in the Institute’s mission statement. “The consequence was the creation of a community of tolerance where the Jewish, Christian and Muslim communities of Spain became part of a larger culture that integrated elements of each tradition.”

When I first visited La Mezquita, it was midnight on a Saturday in New York City. Inside, the mosque is a visually stunning interpretation of the Córdoba original. On entering, one’s avatar is greeted with a stream of text in the chat window, the words unfurling like a scroll, making a request that visitors are free to accept or reject: “While the concept of holy places in a virtual world may stretch the imagination of some, tradition is a major part of history. There is an active Muslim community associated with the Mezquita in Al-Andalus. They have placed a basket with complimentary veils for ladies to cover their hair, and ask that all visitors to the mosque remove their shoes before entering. If you choose to honor this request, you may find your experience enhanced. However, this is strictly a personal decision and there is no requirement that you do so.”

|

| Three avatars meet for prayer, reflection or conversation in the mosque’s prayer hall, which is modeled after the Great Mosque in Córdoba, Spain. |

|

| Meeting in one of the rooms of La Mezquita, avatars Imotali Antiesse and Yekaterina Kalchek are creations of women living, respectively, in Singapore and St. Petersburg. |

I found about a dozen people in the midst of prayer services. (Since sl is accessible to anyone around the world, people participate when it is convenient for them, and because of this, there is an audio option in Al-Andalus that activates the adhaan, the Muslim call to prayer, based on the user’s time zone.)

![“SL is not a substitute for RL [Real Life], but a continuation of it.”](/issue/201004/images/andalus/callout2.gif) Inside the mosque, some avatars walked while some prostrated themselves in prayer. Virtual sunlight shone through latticed windows and reflected dramatically off the long rows of columns made of virtual marble.

Inside the mosque, some avatars walked while some prostrated themselves in prayer. Virtual sunlight shone through latticed windows and reflected dramatically off the long rows of columns made of virtual marble.

After prayers ended, I spoke to three avatars. Yekaterina Kalchek is the avatar of a ballerina in St. Petersburg, Russia. She was there for her morning prayer. Imotali Antiesse told me she was in Singapore, where she had come to pray at lunch time.

Khalid Easterling used a digital translation device to tell me that he was the avatar of an accounting student in Jiddah, Saudi Arabia. As he spoke, his greetings appeared as double-decker text, in Arabic and English, across my screen. “i am from kingdom saudi arabia ... jiddah city.”

Yekaterina explained that she came to sl after a dancing injury confined her to bed for a number of months. “I decided to do something before I went mad with boredom…. I kinda wandered around with the vague idea of writing a story about sl and then discovered Al-Andalus as a tourist. Loved it and discovered it had a Muslim community and so I bought a house and stayed.”

Imotali signed up for sl in 2009 as an assignment for a university course on information systems in Singapore. When she discovered Al-Andalus, she stayed beyond her class assignment. Now, she says, she prays in Al-Andalus’s mosque as a form of nawafil, the optional prayers performed outside the prescribed daily prayer times. She does this, she said, because her mosque in Singapore is very crowded, and women pray separately from men. In sl, however, she likes praying in the main hall in La Mezquita, where, she said, “I feel communication with Allah easier.” She also likes, she said, the “antique structures” of Al-Andalus’s mosque.

Imotali signed up for sl in 2009 as an assignment for a university course on information systems in Singapore. When she discovered Al-Andalus, she stayed beyond her class assignment. Now, she says, she prays in Al-Andalus’s mosque as a form of nawafil, the optional prayers performed outside the prescribed daily prayer times. She does this, she said, because her mosque in Singapore is very crowded, and women pray separately from men. In sl, however, she likes praying in the main hall in La Mezquita, where, she said, “I feel communication with Allah easier.” She also likes, she said, the “antique structures” of Al-Andalus’s mosque.

She was quick to point out that sl is not a substitute for “rl” (real life), but a continuation of it. While prayers in sl don’t fulfill the necessity to perform them physically, too, she said that she feels the spiritual presence of the mosque in the sl environment just as she does in the physical one. She described how much she enjoys being able to activate and listen to the call to prayer in a “place that looks so real.” Yekaterina agreed.

Imotali and Yekaterina simultaneously agreed that their sl experiences have changed their perspectives in the physical world. Imotali explained that “with the governance and community here, everyone is basically kind and respect one another…. Everyone wants to learn from each other…. That’s the most humble thing I see personally…. True, there might be some rudeness or harsh issues,” she added, “but everyone simply wants to try and get along well.”

Yekaterina substantiated this. “Part of the pleasure of sl is meeting people with other backgrounds and beliefs…. I pray with a lady who is Jehovah’s Witness and another lady who is from Church of England.” All three of us, she said, “share a love of God.”

And all of them, Yekaterina said, feel changed by the experience. “Because we share a love of God, and because they learn I am a normal, peace-loving woman.”

Later, I spoke again with founder Rose Springvale. “That’s the fascinating part,” she said. “The thing that attracts people to this project is a desire for understanding, communication and change. The premise is that it is much harder to drop a bomb on someone if you have looked them in the eyes and recognized them as human beings, with jobs and kids and worries of their own.”

|

Joshua Fouts is Senior Fellow for Digital Media and Public Policy at the Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress, a non-partisan ngo. His research, carried out with Rita J. King, was supported by the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, funded by a grant from the Richard Lounsbery Foundation. It can be accessed on the Web at http://dancinginkproductions.com/projects/understanding-islam-through-virtual-worlds/. |