|

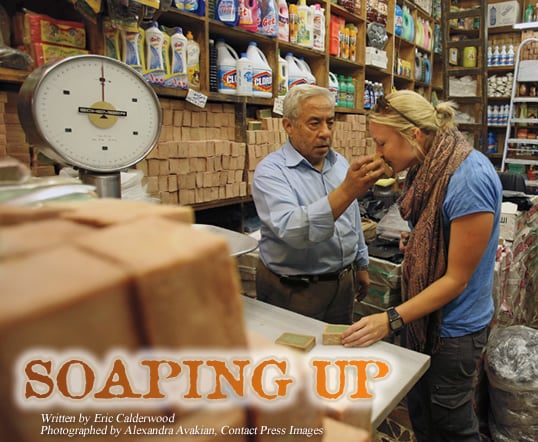

| A customer savors the smell of handmade soap in Mohamed Adel Qaymuz’s shop. Tourists are an important market for traditional soaps in Aleppo. |

|

|

| Olives from groves around Aleppo provide most of the oil essential to traditional soap-making. The best soaps tend to have high percentages of laurel oil as well. |

Colorful stalls packed high with traditional yellow and green bars—soap made from olive and laurel oil—punctuate the madinah's streets. And while many of Aleppo's traditional soap factories have either closed or moved to industrial areas on the city's outskirts, those that remain are easy to locate. Just ask any of the soap vendors for directions, or follow your nose: The overpowering smell of laurel leaves should lead you there.

A great place to start learning about Aleppan soap is the Qaymuz family's famous stall, located in the Suq al-'Attarin (the perfumers' market), the madinah's main commercial thoroughfare. When I visited in January, I was greeted by Aladdin Qaymuz, the owner's son.

Aladdin is 25 and has been working in his family's store since he was nine. "Arabs, Syrians, Aleppans and foreigners" buy his family's soap, he said, specifying that most of the latter are French or Asian, members of the large tour groups that pass through the Aleppo suq.

"Do you still use the soap?" I asked. "I love this soap!" Aladdin exclaimed, but then added that he uses it only to bathe and that—unlike his grandmother—he uses a mass-produced shampoo to wash his hair. "We are the new generation," he explained. "But Momma still uses only the laurel-oil soap for her hair and body."

|

| Omar Joubaili’s family’s factory in Aleppo is a former caravansarai. Here, olive- and laurel-oil soaps dry and ferment. |

Aladdin is not the only member of his generation whose preference for traditional Aleppan soap is on the wane. Throughout my visits to factories and stores in the soap-making capitals of the Levant, I heard the same lament: Sales of traditional soap are declining. Prices and mass marketing are the most important reasons.

It's an uphill battle for traditional soap-makers: Mass-produced soap, which contains cheaper ingredients such as palm oil, has become more affordable than the handmade olive- and laurel-oil soap used by Aleppo's older generation. Companies are able to use the money they save on cheaper ingredients to invest in more expensive ad campaigns instead. In addition, soap stores in the Levant traditionally arrange bare bars in colorful stacks and sell them by weight, a method that consumers are finding less appealing than the attractively wrapped and advertised western-style brands. Amid changing market conditions, the future of traditionally made soap, once a staple good throughout the Levant, is in doubt.

In response to this challenge, many traditional soap-makers in both Syria and Lebanon have developed a new marketing strategy: First, they have adopted the packaging practices used for western bath and beauty products. Then, they are marketing their soaps as "natural" and "organic," hoping to meet growing demand for this type of product in Europe, the us and the nearby Gulf countries. Finally, a number of traditional soap-makers are also taking to the Internet to tout their products' qualities.

|

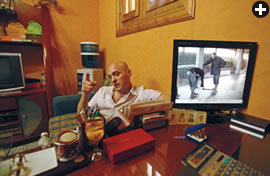

| As a video showing traditional soap-cutting at his father’s factory plays on his desk, Mohammed Jameel Kurdi, another professional in a changing industry, talks about the modern soap-manufacturing company he’s built to bring his family’s products from Aleppo to the global marketplace. |

The Qaymuz family's store, like the family itself, exemplifies the tensions in Aleppo's soap industry. To remain profitable, the family has had to diversify the shop's product line. Juxtaposed with stacks of olive- and laurel-oil soap are packaged European soaps and cleaning products. Indeed, I had the impression that the shop's multitiered soap display, showing all the possible shades of green and yellow, was meant to attract foreigners like myself rather than local buyers. Aladdin confessed that his Aleppan customers are purchasing more of the "modern" products and less laurel-oil soap these days. Even his regular patrons are buying around half of what they used to, he said.

Aladdin reminisced about his childhood, remembering when the store sold only laurel-oil soap: the lowest quality for washing clothes, the middle quality for hand-washing, and the highest quality for the body and hair. Two factors determine the overall quality of the soap: the percentage of laurel oil it contains and the length of time it has been aged.

The Qaymuz shop carries the Joubaili brand of soap, which features an eight-star rating system that reflects the percentage of laurel oil in each soap bar. Soaps with a higher percentage of laurel oil are more expensive because laurel oil is harder to acquire than olive oil, the main ingredient; they are more desirable because laurel oil gives the soap additional moisturizing and antiseptic properties. At the Qaymuz shop, one-star soap costs 250 Syrian pounds a kilo ($2.36/lb), and the highest-quality, eight-star, variety costs 450 pounds a kilo ($4.23/lb).

The Qaymuz family also classifies its soap by how long it has aged: from three months to eight years. Olive- and laurel-oil soap improves with time because the aging process allows it to ferment and dry. As it dries, the soap loses up to 30 percent of its moisture content, and its color changes gradually from green to golden yellow. The aged soap has a darker and rougher surface, but, when cut open, its aroma is more complex and herbal, lingering in the nose for several seconds. The more aged soap is also better for the skin.

To understand the challenges and costs involved in producing traditional soap, you can visit the Joubaili family's factory. On a clear day last October, I tracked it down in the madinah and met the manager, Omar Joubaili. His great-grandfather had been a merchant who made his fortune in Egypt and then returned to his native Aleppo. In the late 19th century, he partnered with Marco Pli, the Italian ambassador to Syria, to buy a khan, or caravansarai, in the old city and convert it into a soap factory. The Joubaili family has been one of the major soap producers of Aleppo ever since. Omar's name is actually 'Amr, but he told me that he had changed his name in English to Omar—"like Omar Sharif," he said with a laugh—because his American friends couldn't pronounce his real name. He told me that I was the first American to visit his factory, and he was thrilled to talk about soap.

|

| One handcrafted bar at a time, Mahmud al-Sharkass plies his trade at his family’s 200-year-old soap workshop in the Khan al-Masriyyin (Egyptians’ Khan) in Tripoli, Lebanon. He and his family make both bar soap—shown stacked in drying towers all around him—and “ball soap,” each ball shaped by hand, some in plain colors, and some marbled with two or more colors. |

When I visited, soap production had not yet begun because the two main ingredients, olive oil and laurel oil, had not yet arrived. The production cycle of traditional Levantine soap is linked to the olive harvest, which extends from September to March. The first pressing of olive oil is used for eating and cooking; the second pressing is for soap. The olive oil used for Aleppan soap comes from the groves surrounding the city, but the laurel oil comes from the mountains of southern Turkey—a few hours' drive north of Aleppo. Omar invited me to return in two weeks to watch the beginning of the soap-production season. "Once we start," he warned, "we work around the clock."

But when I called Omar from Damascus on the prescribed day, I could tell by his voice that he was stressed: Neither the olive oil nor the laurel oil had arrived, even though he had pre-ordered—and paid for—both. He assured me that production would start soon and asked me to postpone my trip by a few weeks. When I contacted him again in early December, he told me that the olive oil had arrived but the laurel oil had been held up at Turkish customs. When I finally returned to Aleppo in mid-December—normally well into the production cycle—Omar's laurel oil shipment still hadn't cleared Turkish customs. Omar had made numerous trips to the Turkish border to try to resolve the problem and had even brought along his brother, who had studied in Turkey and spoke Turkish, to help with the negotiations. Omar never explained the problem to me, but I got the sense that it involved a bribe he didn't want to pay.

But when I called Omar from Damascus on the prescribed day, I could tell by his voice that he was stressed: Neither the olive oil nor the laurel oil had arrived, even though he had pre-ordered—and paid for—both. He assured me that production would start soon and asked me to postpone my trip by a few weeks. When I contacted him again in early December, he told me that the olive oil had arrived but the laurel oil had been held up at Turkish customs. When I finally returned to Aleppo in mid-December—normally well into the production cycle—Omar's laurel oil shipment still hadn't cleared Turkish customs. Omar had made numerous trips to the Turkish border to try to resolve the problem and had even brought along his brother, who had studied in Turkey and spoke Turkish, to help with the negotiations. Omar never explained the problem to me, but I got the sense that it involved a bribe he didn't want to pay.

In the end, Omar didn't start soap production until February this year, early enough to fill his pre-orders from France but too late to match last year's production volume. He gave priority to his European orders, since foreign contracts are more lucrative than the business he does in Aleppo's Old City, so in the end, this year's batch of Joubaili soap would make its way to the French market, but would be surprisingly harder to find in Aleppo's soap stalls. With these delays, the Joubailis only escaped financial ruin because they were cushioned by their savings—an example of the reasons why soap-making in Aleppo is increasingly a gentleman's occupation.

oap producers in Tripoli, Lebanon face similar challenges, but have adopted an aggressive new business strategy to meet changing market conditions. Tripoli is only 85 kilometers (50 mi) north of Beirut, but it feels worlds away from Lebanon's cosmopolitan capital. Along with Aleppo and Nablus (in Palestine), it is one of the three historic centers of Levantine soap production.

oap producers in Tripoli, Lebanon face similar challenges, but have adopted an aggressive new business strategy to meet changing market conditions. Tripoli is only 85 kilometers (50 mi) north of Beirut, but it feels worlds away from Lebanon's cosmopolitan capital. Along with Aleppo and Nablus (in Palestine), it is one of the three historic centers of Levantine soap production.

While Tripoli's soap stalls aren't as prominent as those lining the main streets of Aleppo's Old City, the city boasts more soap-makers than its Syrian sister. And, unlike the relative monochrome of Aleppo's traditional soaps, those in Tripoli are a rainbow of vivid colors. This is just one of the ways in which Tripoli's soap producers are adapting tradition to the modern marketplace.

Tripoli's 16th-century soap market, Khan al-Sabun, is an obligatory first stop in any soap itinerary of the Old City. The industry in Tripoli took off in the 17th and 18th centuries, when, according to the historian Antoine Abdel Nour, the Ottoman Empire, of which Tripoli was a part, established favorable financial regulations mandating the transport of ash, the essential alkaline ingredient in soap, from the desert of Homs and Hama (in present-day Syria) to Tripoli. Two-thirds of this ash shipment was allocated, by law, to the four state-run soap factories that the Ottomans set up in Tripoli. During this boom, Tripoli's Khan al-Sabun became the heart of the local soap industry. From here, Tripoline soaps traveled to points outside the Levant—and even beyond the Ottoman world. In recent years, Badr Hassoun, the scion of one of Tripoli's great soap families, has refurbished the khan and made it the symbolic and commercial center of his multinational soap company—itself named Khan Al Saboun. Although the company's main factory is now in the suburb of Abou Samra, its main offices are still in the khan.

The day I visited, Ahmad Hassoun, Badr's oldest son and Khan Al Saboun's general manager, was testing new facial washing solutions with Dr. Fayek Minkara, the company's chief chemist. Minkara, a portly fellow in his 50's, emphasized the importance of developing new products. He had lived in the uk for nine years, where he completed a master's degree and a doctorate in biochemistry. When he returned to Lebanon, he couldn't find an appropriate job in the academic world, so he joined Khan Al Saboun and taught himself the science of soap. Today, he is in charge of production, innovation and quality control.

Khan Al Saboun's motto is "Tradition and Success"—and that means success in the 21st century, or, as Minkara puts it, making "a family business into a company business." Unlike other soap-makers I met, who seemed to relish the family-sized dimension of their cottage industries, Hassoun's company has bigger goals. Throughout our meeting, Minkara emphasized the word "worldwide." Hassoun pointed out that Khan Al Saboun owns 10 stores in Lebanon and more than 100 outside the country, and has some 1500 franchised dealers worldwide, as well as an ever-expanding Internet presence. The Gulf states are the company's most important foreign market, representing almost 80 percent of its total sales, but it also has major contracts in Russia, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and New Zealand.

|

| Whimsically made to resemble Arab pastries, specialty soaps highlight a storefront in Tripoli’s Khan al-Sabun (Soap Market). |

|

| At the Sharkass workshop, soap made in the form of prayer beads dries on a line. |

|

| Schoolchildren on a visit to the Musée du Savon see some of Sharkass’s carefully crafted soaps sculpted as grapes. |

Nothing could be farther from the Qaymuz family's Aleppan soap stall than the Hassoun family's flagship store in the Khan al-Sabun in Tripoli. There, the bars of soap are individually wrapped in attractive plastic packages or wooden gift boxes rather than displayed in colorful stacks—and one or two bars sell for the price of an entire kilo of Aleppo's finest laurel-oil soap. The store has a more diverse selection of soap shapes and sizes than you'll find in other Lebanese or Syrian soap shops. And a number of perfumed soaps—scented with rosewater, jasmine, lemon, honey and anise—are on display. Despite their stylish presentation, however, the quality of many of Khan Al Saboun's products doesn't match the best of Aleppo's, for they contain palm oil while Aleppan bars are made with olive and laurel oil only.

This underscores the dilemma facing many Levantine soap-makers: Rather than "Tradition and Success," they often have to decide between tradition or success. Omar Joubaili chooses to follow traditional practices and use traditional ingredients; in return, he must deal with declining demand and problems of supply. The Hassoun family has accepted the fact that traditions must adapt to the market. The ends justify the means, says Minkara: "This enterprise is for the Lebanese. We want them to get something out of their culture."

ahmud al-Sharkass, the seventh generation of an illustrious line of Tripoline soap-makers, represents another path for the Lebanese to "get something out" of their soap culture. I first encountered Sharkass's work at the Musée du Savon (Soap Museum) in Sidon, Lebanon, just south of Beirut. This wonderful little museum, established by the Audi Foundation, is housed in a building that used to be a soap factory.

ahmud al-Sharkass, the seventh generation of an illustrious line of Tripoline soap-makers, represents another path for the Lebanese to "get something out" of their soap culture. I first encountered Sharkass's work at the Musée du Savon (Soap Museum) in Sidon, Lebanon, just south of Beirut. This wonderful little museum, established by the Audi Foundation, is housed in a building that used to be a soap factory.

|

| Handmade soaps, elegantly wrapped and displayed in glass cases, make for high-end trade at Hammam (“Bath”), the shop at the Musée du Savon (Soap Museum) in Sidon, Lebanon. The museum occupies a former soap factory, and it traces the history of Levantine soap as both craft and commerce. |

The Audi family bought the factory in the late 19th century, and it remained one of the most important soap factories in Sidon until the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war in the mid-1970's, when the ground floor was occupied by refugees. In 1996, banker Raymond Audi transformed his family's old soap factory into a museum about the history of Levantine soap. It features a 12-minute educational video that follows the journey of a young boy through the streets of Tripoli, where he meets soap-makers, buys soap and returns home to bathe. The video includes beautiful images of Mahmud al-Sharkass at work in his factory in Tripoli, and the museum shop, called Hammam ("Bath"), carries Sharkass's signature product: shiny, multicolored, marbled soap balls.

|

| Soap stamps, each carrying its maker’s branding mark, hang in front of a soap wall at the Musée du Savon. |

Sharkass's store is in Tripoli's Khan al-Khayyatin (Tailors' Khan), which has been beautifully restored by the Spanish government, but his workshop is in the nearby Khan al-Masriyyin (Egyptians' Khan). This khan also houses Tripoli Soaps, run by Abdoulwahed Hassoun, a relative of Badr Hassoun.

Such a concentration of master soap-workers undoubtedly makes the Khan al-Masriyyin the best place in Tripoli—and perhaps in the whole Levant—to learn about soap. Sharkass works in cramped quarters on the khan's second floor, where his family has been making soap since 1803. He sits on a small stool set among the "drying towers" of yellow soap being aged.

|

| Flanked by soap-drying towers, students learn about Levantine soap-making at the museum. |

Sharkass and his family were gracious hosts, but they never stopped working throughout my visit. Sharkass produces about a hundred multicolored soap balls a day, some of which he sells in his store and some of which he sends to Hammam. The soap balls are labor-intensive creations, requiring two days of molding. Sharkass's son, Ahmad, and his daughters use large basins at the back of the workshop to cook olive oil and caustic soda into soap paste. Sharkass injects this paste with food coloring that he buys from pastry chefs. Then he takes a fistful of the paste and molds it in the hollow of his hand, forming a ball. He gives each ball a uniform shape and leaves them to dry overnight. The next day, he scrapes the soap balls with a polishing tool (called a shafrah), giving them a bright, shiny finish. He also molds small, plates of soap on which he displays the soap balls at the front of his shop.

Sharkass, who was born into the soap-making business like Badr Hassoun and his son, showed me pictures from the 1940's of his father making soap balls in the same workshop. Likewise, Sharkass is training his son to take over the store when he retires.

In fact, I soon learned that the whole family—including his wife and daughters—works in the shop and knows how to make the colored soap balls. Nevertheless, when I asked the mother and youngest daughter for their names, they told me that I should only write down the names of the father and the son because "the shop is theirs." Soap-making is a vocation that consumes the whole family, but the title of "soap-maker"—like most artisanal titles in the Levant—is passed down from father to son.

I was struck by the immense differences between the Sharkass and the Hassoun families, despite the similarities in their family histories. In a single generation, Badr Hassoun has turned his company, Khan Al Saboun, into a multinational corporation, while Sharkass's workshop remains very much a "family business" in scale and ethos. The Hassoun family has moved its soap production out of the Old City to a large factory, while Mahmud Sharkass continues to labor in the workshop he inherited from his father. Finally, the Sharkass family has continued to work with soap on a daily basis, molding multicolored soap balls by hand. The Hassouns, in contrast, administer their soap empire from offices located symbolically in the historical soap-making khan.

|

| Soaps in brightly colored wrappers light up the Sabunna soap shop in Sidon. Although that city’s heyday as a soap-making center has passed, it still offers traditional soap for sale. |

The two families do, however, share a common goal: They're both looking for new markets for a traditional product. The Hassouns have a network of dealers outside Lebanon and increasingly look to make their profit in the Gulf countries and in Europe. The Sharkass family sells its wares directly from its workshop, but they also have a contract with the Audi Foundation, which is able to market their products in an upscale tore—Hammam—designed to attract tourists. Thus both families have, to some extent, accepted the transformation of Levantine olive-oil soap from a staple good, bought and used by Lebanese families of all classes, to a luxury good intended for affluent customers.

While the Hassoun family has moved soap production out of public view, Mahmud al-Sharkass relies on the artistry of his craft, displayed in his workshop and in the Soap Museum video, to attract customers. The question for both families, however, remains: Will customers continue to pay more for such products, particularly when they are increasingly difficult to distinguish from the mass-produced "natural" soap and beauty merchandise that is taking up more and more shelf space in the market?

|

Eric Calderwood ([email protected]) has written on the Middle East, North Africa and Europe for The American Scholar, McSweeney’s and the Boston Globe. He traveled to Syria with the support of a Fulbright-Hays grant from the us Department of Education. He is a doctoral student at Harvard University, where his research focuses on the literature and history of Spain and Morocco. |

|

As a senior photographer at Contact Press Images, Alexandra Avakian (www.alexandraavakian.com) has photographed for leading world publications since the 1980’s. Her book Windows of the Soul: My Journeys in the Muslim World was published in 2008 by National Geographic/Focal Point. |