For students:

We hope this guide will help sharpen your reading skills and deepen your understanding of this issue's articles.

For teachers:

We encourage reproduction and adaptation of these ideas, freely and without further permission from

Saudi Aramco World, by teachers at any level, whether working in a classroom or through home study.

— THE EDITORS

Jump to McRel Standards

Activities

We humans have many ways of saying things. Sometimes we say them in words, but there are lots of other

ways to say things. The activities in this Classroom Guide will help you explore different ways that we communicate

with each other. You will find Visual Literacy activities embedded in them.

Theme: Ways of Speaking

How do you “speak” without talking? Why do you do so?

There are things you say in words and things you don’t. For example, when you roll your eyes in response

to something someone has said, you’re not saying anything in words, but you’re communicating a message

nonetheless. Think for a minute about this: If you’ve ever rolled your eyes, what did you mean? Jot down

one sentence that puts into words what you were “saying” when you rolled your eyes. (If you’ve never rolled

your eyes, you’ve certainly seen other people roll theirs. Write a sentence that summarizes what you

understood them to be saying.) Now share your sentence with a partner. Discuss with your partner why

someone might choose to roll his or her eyes rather than speak the sentence in words.

How do objects “speak”? What do they say?

In addition to facial expressions conveying meaning, objects can communicate meaning too. Have you seen

anyone wearing a pink ribbon? The ribbon, in a way, is speaking: It is communicating a message from the

person who is wearing it to whomever that person sees. What does it mean to you when you see the pink

ribbon? If you saw someone wearing one and didn’t know what it meant, would you ask? Why or why not?

“For My Children” includes a discussion of pink ribbons. Look at the photos on page 9 and read the captions,

in which Dr. Samia Al-Amoudi writes about pink ribbons. How does she describe what the pink ribbon is “saying”?

Think about other objects that convey meaning—such as ribbons of other colors. With your partner, join

another pair and brainstorm a list of such objects. Write them in the left column of a T chart. In the right

column, write a tweet that expresses what the object is saying. Be specific. For example, for the pink ribbon,

don’t just write “breast cancer.” Write something more thorough (but still brief), such as, “I support research

that will end breast cancer,” or “I am aware that some women get breast cancer, and I support efforts to find

a cure.” When you’ve completed your T chart, discuss, as you did regarding rolling your eyes, why someone

might prefer to communicate a message with an object like a pink ribbon rather than to say something in words.

Like pink ribbons, sculptures can communicate meaning. Read “Egypt’s Granite Garden.” Then look at the

photos of the sculptures and read the captions, many of which simply name a sculptor and identify the year

in which he or she created the art. Choose one of the sculptures to focus on. Write a few sentences that

summarize what the sculpture says to you. Then find another person in the class who has looked at the

same sculpture. Read aloud to each other what you have written. Did the sculpture say the same thing to

both of you? If not, explain to each other how you “heard” what you did from the sculpture. Does it matter

to you that you heard something different than your partner? Why or why not? Have a few pairs share their

descriptions with the rest of the class. As a class, discuss differences in how different people understand

what a sculpture is saying.

|

As a way to think more about non-verbal ways of “speaking,” look at the photographs that accompany

“Kazan: Between Europe and Asia.” With your partner, look at facial expressions, gestures, objects and

actions in the photos. Discuss what they say to you. Keep in mind that they may communicate different

things to different people, which raises the question you also considered when looking at sculpture:

How important is it that people accurately receive the message that someone intends? Think again about

the example of rolling your eyes. What if you were in a place where that facial expression meant that

you were feeling ill? Or maybe it was considered a prayerful expression. Or maybe it had no meaning

at all. In a situation in which you were rolling your eyes, how important would it be to you to have

someone understand your meaning? How important do you think it is to Dr. Al-Amoudi that people

understand what a pink ribbon means? In short, in what kind of situations does accurately understanding

the meaning of a gesture or an object matter? In what kinds of situations doesn’t it matter? What accounts

for the difference?

How do photographs speak?

You’ve just looked at some photographs to see how expressions, objects and actions convey meaning.

If you think about it a little more abstractly, sometimes people use photographs to say things, rather

than saying them in words. If you post pictures on Facebook, for example, why do you choose the

photos rather than describing some things in words? Again, think back to the example of rolling your

eyes. Are there times when it’s better not to say something out loud? Are there some things that are

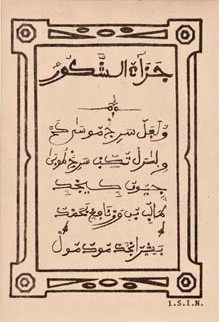

too complicated to say in words, that photos communicate more efficiently? “From Africa, in Ajami”

includes photographs of pages written in Ajami. Read the article, underlining parts that describe what

Ajami is and what it looks like. Then look at the photos and read the captions. Why do you think the

editors of Saudi Aramco World decided to include photos of these pages? What, if anything,

do the photos convey that the words of the article do not?

When might you prefer not to speak about something? Why?

Read “For My Children.” In it, Dr. Al-Amoudi discusses how difficult it was for her to talk with her children

about her illness, but that she did so anyway. Think about why it was difficult for her to speak about it,

and why she did anyway. Then think about things you find difficult to talk about. In a journal, find a way

to express this. You might choose to write about it, but you might prefer to draw, take a photo, or use

some other medium. You don’t need to show this to anyone.

Theme: Reading, Writing and Speaking

Now that you’ve thought about different modes of communicating, turn your attention to what is more

typically associated with communication: reading, writing and speaking.

What’s in an alphabet?

“From Africa, in Ajami” provides a rich example of a written form of communication. Read

the article and highlight or underline the answers to these questions: What is Ajami? What

analogy does writer Tom Verde use to help readers understand what it is? How did Ajami

develop? Where did it develop? How did it spread? Think about who uses Ajami and what

they use it for. Write a sentence or two about what you think might make Ajami important.

Why do people have power struggles about a form of script? What is at stake?

The answers you’ve highlighted are fairly

straightforward, and yet there’s more to the story of Ajami. Maybe you find it surprising

that a form of script can be controversial. After all, how controversial is the English alphabet?

Even young schoolchildren see it every day on charts around their classrooms! But Ajami

is controversial. Let’s take a closer look to find out why. First, look at how you know that

Ajami is controversial. Using a different color highlighter or pen, mark the parts of the

article that present evidence that shows that some people reject the use of Ajami. Then

go through and mark the parts that explain who—past and present—has opposed the use

of Ajami, and why. Write a sentence that summarizes their perspective(s).

|

On the other side of the issue are those who believe that the acceptance of Ajami could

empower the people who read and write it. Who are these people? Underline the names

and jobs of those who believe that official recognition of Ajami could be important. Then

mark their explanations of what that recognition could provide and what it could reveal.

When historians study a time period, they use artifacts, including writings, from that time period.

The way they understand the past hinges on what kind of documents they look at. Take the

example of the industrial revolution. If you read business documents from early textile mills, you

would get a story about industrialization from a businessman’s perspective. You might learn about

production methods, the cost of materials, the quantity of output and the profits earned. But if you

read the diaries of young women who worked at the mills, you would learn about how difficult the

work was, how long the workday lasted, how much—or how little—money workers earned, what

they did in their spare time, and so on. The documents you read, in other words, shape the story that you learn.

Think about Ajami in that context. What kind of documents—analogous to the workers’ diaries—can

you imagine might be available in Ajami that are not available in other forms of writing? As a class,

brainstorm examples of such documents. Then imagine what kind of information such documents

might provide. What kind of story might they tell—and most importantly, how might it differ from

the stories people know now?

Why do people have power struggles about a language? What is at stake?

“Kazan: Between Europe and Asia” reports that the Tatar language, like Ajami script, has been the object

of power struggles. There are parallels between the experiences of the Tatars and those of Africans who

read and write Ajami. Mark the places in the article that show that there are power struggles involving the

Tatar language and Tatar culture. With a partner, make a list of similarities between the power struggles in

Tatarstan and those regarding Ajami.

Think about other current examples of conflict over language and identity. For example, in the parts of the

United States that border Mexico, the use of Spanish in public schools is often controversial. Do some

research to find out why. What is at stake when people use a language that is not the officially recognized

language in a place? Why does the language people use become important and controversial?

Finally, reflect on what you’ve learned. What surprised you most about what you’ve read and done? Why was

it surprising? Did it contradict something you thought before? Is it something that had never occurred to you?

As a way of concluding these activities, write an email to your teacher answering these questions.

From Africa, In Ajami

Geography

Standard 9. Understands the nature, distribution and migration of human populations on Earth's surface

Standard 10. Understands the nature and complexity of Earth's cultural mosaics

Standard 11. Understands the patterns and networks of economic interdependence on Earth's surface

World History

Standard 13. Understands the causes and consequences of the development of Islamic civilization between the 7th and 10th centuries

Standard 18. Understands major global trends from 300 to 1000 CE

Standard 30. Understands transformations in Asian societies in the era of European expansion

For My Children

Behavioral Studies

Standard 3. Understands that interactions among learning, inheritance, and physical development affect human behavior

Standard 4. Understands conflict, cooperation, and interdependence among individuals, groups, and institutions

Health

Standard 2. Knows environmental and external factors that affect individual and community health

Standard 8. Knows essential concepts about the prevention and control of disease

In Melville’s Shadow

United States History

Standard 12. Understands the sources and character of cultural, religious, and social reform movements in the antebellum period

Language Arts

Standard 6. Uses skills and strategies to read a variety of literary texts

Kazan: Between Europe and Asia

Theatre

Standard 6. Understands the context in which theatre, film, television, and electronic media are performed today as well as in the past

Geography

Standard 10. Understands the nature and complexity of Earth's cultural mosaics

World History

Standard 13. Understands the causes and consequences of the development of Islamic civilization between the 7th and 10th centuries

Standard 45. Understands major global trends since World War II

Egypt's Granite Garden

Visual Arts

Standard 4. Understands the visual arts in relation to history and cultures

Geography

Standard 10. Understands the nature and complexity of Earth's cultural mosaics

World History

Standard 6. Understands major trends in Eurasia and Africa from 4000 to 1000 BCE

| Julie Weiss is an education consultant based in Eliot, Maine. She holds a Ph.D. in American studies. Her company, Unlimited Horizons, develops social studies, media literacy, and English as a Second Language curricula,and produces textbook materials. |