Photographed by Stephanie Keith

Written by Sarah Gauch

| |

|

|

On the set of Kanaria and Company, Lucy plays Madiha, who in this scene waits to meet her husband for the first time since he was jailed for counterfeiting—and sets in motion a great deal of scripted intrigue. |

|

|

or the cast and crew of the new television serial Kanaria and Company, the day is not going well. They were supposed to shoot street scenes, but the cars arrived two hours late. The star didn’t show at all because he hadn’t been paid. Now they’ve been thrown off their location—the driveway of a glitzy, five-star Cairo hotel—for not getting permission to film there.

or the cast and crew of the new television serial Kanaria and Company, the day is not going well. They were supposed to shoot street scenes, but the cars arrived two hours late. The star didn’t show at all because he hadn’t been paid. Now they’ve been thrown off their location—the driveway of a glitzy, five-star Cairo hotel—for not getting permission to film there.

The crew and their equipment move to the sidewalk and spill over into a street of honking cars. A rickety donkey cart veers frighteningly close to the female lead, who is wearing a sleek black pantsuit and sunglasses encrusted with faux diamonds.

Every television production has its delays, but Kanaria and Company has had more than its share. As one of about 60 Egyptian musalsalat—television serial dramas—vying for 12 local airtime slots during Ramadan, plus several more schedule slots on pan-Arab satellite channels, Kanaria and Company’s star cast, top scriptwriter and noted director—all Ramadan television “regulars”—face their stiffest competition ever. With less than three weeks to go until the Islamic holy month begins and only about five of its 34 episodes ready, Kanaria and Company is feeling the heat.

Musalsalat have long been a staple of television production in Egypt, historically the Arab world’s capital of film and television, and in many other Arab countries. However, the most and the best have always been produced for Ramadan. Just a decade ago, there were only about 12 productions annually. The five-fold increase is largely due to the proliferation of satellite outlets, as well as the migration of talent from the movie industry to television as Egypt’s film industry falters for technical, logistical and financial reasons in the context of the country ’s overall economic woes and the increasing dominance of the ubiquitous tube.

|

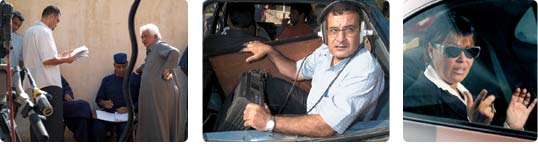

| The popular director of the series, Abdel Hafez, with his signature white hair and galabiyah (robe), discusses a scene with his crew. For a car shot, the sound man rides under the hatchback; for another car shot, Lucy practices a final line from the back seat. |

The past decade has also witnessed the resurgence of new and improved musalsalat from other Arab countries—especially Syria, Lebanon and Jordan—as well as pan-Arab productions for which, for example, a producer from the Gulf may bring together a writer from Jordan, a Syrian director, actors from Lebanon, Syria and Morocco and technical specialists from all over the Arab world, or even from Europe, to produce serials of impressively high quality. In the past five years in particular, these have started to outshine the dominant Egyptian dramas—but they have followed the pattern of their Egyptian counterparts by saving the best of their productions for Ramadan broadcast, thus making the fight for airtime and audience attention during that month even fiercer.

These Ramadan serials, wherever they are produced, range in their subject matter from contemporary social stories to historical epics to comedies. Some people call them soap operas, because they can be excessively melodramatic, with cliffhanger endings in each episode. But unlike America’s never-ending and sometimes tawdry soaps, Arab musalsalat, and Egypt’s in particular, show little skin, have a limited number of episodes and sometimes include a serious message for the country’s—and the Arab world’s—mass audience. And over the years they have grown so popular that they have become for many the favorite entertainment during the devout month of sunrise-to-sunset fasting and prayer.

|

|

|

|

Left: Working as extras on the set of Man of Destiny, a historical drama of the conquests of ‘Amr ibn al-‘As, the general credited with bringing Islam to Egypt in the seventh century, a band of “Roman soldiers” takes direction as they prepare to deal with a group of “Egyptian prisoners,” above. The musalsalat are a boon to part-timers seeking cash as extras, and the same extra may work in any number of Ramadan productions. |

Highlighting the role of these serials as entertainment during Ramadan, Hassan Hamed, chairman of the Egyptian Radio and Television Union, says, “You can’t think of Ramadan without thinking of the television serials. So many people are gathered to break the fast at the same moment, so many pray all in unison. Then comes the television, and everyone gathers together to watch.”

The musalsalat are the best of Egypt’s yearly television offerings. They become the topic of national conversation and they garner the highest advertising revenues. What makes the competition among the programs and the anticipation of the viewers more intense than in any western counterpart is that no one—neither the public nor the stars nor the directors nor the broadcasters—knows which serials will show on the mass-appeal local stations until the government-run Policies Planning Committee announces its decisions, sometimes only a couple of days before Ramadan begins. Although Egyptian, Arab and other satellite channels also broadcast the dramas, only 20 percent of Egyptians have access to satellite television, and thus the greatest popular renown is still won through the four local government-run channels.

| |

|

|

Man of Destiny extra Nisreen Dashoush works most of the year as a model; here she relaxes in Media City’s cafeteria after a shoot. |

|

|

For Kanaria and Company and some other serials, though, the Policies Planning Committee’s decision may be moot if they can’t finish shooting in time for Ramadan. Ideally, a Ramadan serial needs six months to shoot, but the Kanaria and Company crew is trying to do it in four. There have been constant delays and money problems, in addition to the simmering chaos typical of any film or television production in the world.

|

| From left to right: An animal wrangler prepares for a scene in which a poor farming couple discovers riches in their barn. ‘Amr ibn al-‘As is played by Nour El Sherif, one of the country’s best-known actors, shown here among extras portraying Romans. In the series Women of Islam, actor Nabil El Hograssy takes a break from his 13th-century role. |

|

|

|

Well-known comic actor Ashraf Abdel Baky practices lines with star actress Rugina in Tales of a Modern Husband, set in a suburban Cairo apartment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Abdel Baky meets a young fan outside the set. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“You see how we’re sitting here,” says the female lead, who is known only by her first name, Lucy. She is sitting nonchalantly on the sidewalk as cars and minibuses careen past, her rhinestone sunglasses still wrapping her eyes. “The shooting was supposed to start two hours ago.” Eventually she does see some action: She drives off in a white Hyundai piloted by a man in a purple suit and tie, camera crew trailing.

Everyone on the set agrees that it’s non-negotiable: Kanaria and Company, with its

million-dollar budget, must finish on time. After all, it would be very awkward for the musalsalat to launch without a serial scripted by Osama Okashah, who since 1976 has authored some 40 musalsalat—or without one by director Ismail Abdel Hafez, who since 1986 has directed some of the best of all time—or without Farouq Fishawi, the series’ lead and a popular film and television star. Besides, Kanaria and Company is potentially a real money-maker. According to Emad Abdullah, general manager of its production company, the show has already signed a contract with one Arab satellite station, and it could sign with a dozen more. And if it can earn a top local-channel slot, there’s more money to be made from advertising. And ultimately, it’s a good story: A counterfeiter discovers after getting out of prison that the justice system is far more forgiving of his past crimes than Egyptian society.

Unfortunately, if Kanaria and Company doesn’t finish on time, there are plenty of others to fill its slot. In Egypt, there’s Malak Rohi, with Egypt’s leading female star, Yosra. There is Come, Let’s Dream of Tomorrow, featuring superstars Leila Elwi and Hussein Fahmi. And there is respected film director Khairy Bishara’s first try at television, It’s a Matter of Principle. From other Arab producers, there are the historical serials Rabi’ Gharnatah (The Spring of Granada), Al-Hajjaj and ‘Umar al-Khayyam and the social drama Al-Liqa’ al-Akhar (The Other Meeting), among many others.

In any case, Kanaria and Company’s cast and crew aren’t the only ones worried about finishing on time. Similar concerns haunt their counterparts in the historic-religious serial Man of Destiny, in which superstar Nour El Sherif plays the lead role of ‘Amr ibn al-‘As, the seventh-century Arab general largely credited with bringing Islam to Egypt.

“We’re all nervous,” says actor Yaser Maher, who plays a friend of the lead. “Because the Islamic stories have their biggest audience during Ramadan, we’ll probably have to wait another whole year if this serial doesn’t air.”

During Ramadan, which is also the most social month of the year, the musalsalat run from the morning to the wee hours of the following day. And they run everywhere. Television sets are not only in homes, but also in public places—restaurants, hotels, stores and even outdoor sports clubs. According to Nabil Dajani, professor of communications at the American University of Beirut, television allows a family-centered culture to entertain

in their own homes for free. Friends and families gather to surf channels in search of the best programs, to discuss the characters and to debate the wisdom of their decisions.

|

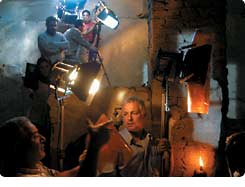

| Actors prepare for a night scene in Media Production City. On screen, their melodrama and the cliffhanger endings of episodes lead some to call the musalsalat “soap operas,” but the English term is too narrow for all that the musalsalat offer. In the control room, an editor assembles footage for Women of Islam. |

| |

|

| |

top: Nermeen Abdallah readies her family’s table for iftar, the post-sunset meal that breaks the daily Ramadan fast. Later, bottom, her husband Aziz and other family members relax at home for the evening with a few musalsalat.

|

| |

|

| |

Young men do their watching into the wee hours at a café. |

|

|

The musalsalat’s popularity, says Dajani, lies in their portrayal of problems and concerns that could easily be those of the average person. People also learn from them: The government has long used them to educate the public and shape public opinion. Although there is less state control of Egyptian television today than in the past, the producers, to varying degrees, are still aware of the serials’ didactic power. “I think these soap operas are absolutely terrific, the way they get their message across indirectly,” says Dajani. He describes one that sent a positive message about Muslim-Christian relations by showing a Muslim man who had gone bankrupt being deserted by all his friends but one, a Christian. Others depict the evils of greed, denounce religious militancy or extol hard work and patriotism. With the largest number of viewers being women, there is an abundance of strong female characters, and there are frequent allusions to women’s rights.

Of course, some say the stories are largely hack work. “There’s nothing interesting,” says Summer Said, who writes on culture for the English-language weekly The Cairo Times. “I’m really fed up with the same themes. They’re either about Egyptians 50 years ago, or love stories, or very rich people. I’d like to see something new. Or maybe keep the old theme, but deal with it from another angle.”

Cutting edge or blunt instrument, three days before Ramadan Kanaria and Company has more immediate concerns. In the last two weeks, it has completed only two more hours of finished production, and it has eight to go. Things are not looking good. Gathering on today’s set, the “villa”at Media Production City outside Cairo, cast and crew show the pressure and exhaustion in the deep circles around their eyes and their dark, furrowed brows. At five p.m. director Abdel Hafez, immediately recognizable by his white mane of hair, arrives and struggles out of his silvery turquoise car. After shooting until three that morning and editing until seven, he is tired, his eyes are puffy, and white bristles dot his chin. “He’s 64,” a crewmember says. “His health won’t take this.”

Abdel Hafez walks onto the roof-top set in his trademark galabiyah, the traditional full-length robe, barely greeting the crowd that soon gathers around him. The cast and crew now know that the Policies Planning Committee didn’t pick Kanaria and Company for a local channel because production was so far behind schedule. Still, the series can still show on the local channels after Ramadan, and on Arab satellite stations during Ramadan—if they can finish. The crew says they’ll work 20 hours a day, maybe even until the last day of Ramadan, toward the end of the month airing at night what they shoot during the day.

The mounting pressure makes Abdel Hafez nervous, however. “The closer Ramadan gets, the faster we work, and any mistake can lead to a disaster,” he says. “There’s always the fear that we won’t finish, but what scares me the most is that the quality of the work will suffer.”

|

|

|

| Khalid Gabry, lighting director of the historical television series “Man of Destiny,” discusses light placements for a scene on a barnyard set in Cairo’s Media Production City. A Ramadan series has 28 episodes, each usually 45 minutes long—an amount of footage that makes for considerable hustle on the set: This scene took only 15 minutes to light. Photograph by Stephanie Keith. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The following day, on the set of Man of Destiny, a row of Roman soldiers stands in a turreted “fort,” pointing bows and arrows at a motley group of Egyptian “prisoners” in chains. Although all is not well for the Egyptians in this scene, the situation is looking up for this serial: The Policies Planning Committee chose it to run at midnight on local channel one.

“That’s the best time,” says Moutaz Metawi, the director’s first assistant, who is clearly pumped at the news. “People will see it. They’ll be up to see it.”

The origins of musalsalat in Egypt and the rest of the Arab world go back centuries, some say, to storytellers and shadow-play performers who told serial tales in cafés during Ramadan nights. Others say the origins lie in the classic format of The Arabian Nights, known in the Arab world as One Thousand and One Nights, the famous Arabic series of “to-be-continued” stories. Other scholars see modern connections. “I see them harking back to modern film and somewhat to modern literature,” says Lila Abu-Lughod, professor of anthropology at Columbia University in New York. “It’s a modernist genre with its own conventions of narrative and acting.”

In the 1920’s, radio serials began transfixing Ramadan fasters. The television musalsalat began to appear in the 1960’s, and since the 1990’s revolution in satellite broadcasting, they have become only more popular. In recent years Egyptian and Arab private investors have joined the Egyptian government in financing them, though private money still makes up only an estimated 10 percent of the total.

Other Arab countries produce musalsalat for Ramadan too, but they sometimes attract fewer viewers and are often of lesser quality. However, Egypt’s main serious rival, Syria—where the shows’ political and social messages are surprisingly bold—has presented a consistent string of very high-quality, serious social and historical productions in recent years. Pan-Arab productions have also been on the rise and compete fiercely in terms of quality and audience attraction. In any case, whether one prefers Egyptian or Syrian musalsalat, or perhaps an upstart show from, say, Lebanon—or even something from the long list of special Ramadan shows of other types—it is all part of the sociable debate that flourishes every Ramadan.

But this year there is series that nobody is talking about: Kanaria and Company is not even showing on a satellite channel. It was just too far from done. It’s not the only upset of this season. Star actor Yosra’s frontrunner serial Malak Rohi only made it to a satellite channel, and her personal complaint left the Policies Planning Committee unmoved. But Kanaria and Company crewmembers are sorely discouraged. “The series was really good,” says camera engineer Ahmed Moustafa. “We worked so hard and exhausted ourselves.”

As for the public, with so many serials to choose from, it surely doesn’t know what it’s missing. By mid-November, halfway into Ramadan’s month-long television binge, 21-year-old Islamic philosophy student and night-shift baker Ahmed Abdel Aziz says he’s following six musalsalat, watching 10 hours a day. “This is the chance to see the serials,” he says. “There are so many—religious serials, social serials. During the rest of the year, there’s only one a day.” He’s standing in a narrow bakery on a noisy street in the working-class neighborhood of Imbaba. Fresh loaves of bread are stacked in a tall rack of metal sheets. Above them on a shelf sits his small television, blasting superstar Nabila ‘Ubaid’s musalsal Aunt Nour. After that, he says, there’s The Night and Its End, with Egypt ’s famous physician-turned-actor Yahya El Fakhrani, and then, at midnight, Man of Destiny—and more, almost until sunrise.

|

Stephanie Keith ([email protected]) lives in New York, where she is a free-lance photojournalist. Free-lance news and magazine feature writer. |

|

Sarah Gauch ([email protected]) has written for Saudi Aramco World, Newsweek, Business Week, The Christian Science Monitor and other publications. She has been based in Cairo since 1989. |

|

|

Related articles have appeared in these past issues of Aramco World and Saudi Aramco World

Ramadan: J/F 02, M/A 90, M/A 92

Ramadan entertainments: M/J 96, M/A 99