|

|

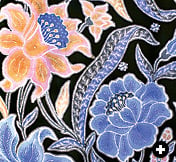

| Detail of a finished Oey Soe Tjoen tulis sarong, in which each dot and line is applied freehand in hot wax. |

Written and photographed by Eric Hansen

In 1975 I made my first visit to the sprawling public market of Jogjakarta on Indonesia’s third-largest island, Java. I was looking for a simple plaid cotton sarong to sleep in during the hot tropical nights, but as I wandered the dim and crowded aisles of the covered market, I found myself lost in a section devoted to second-hand batik sarongs. A woman held up an old one that caught my eye. The design, of butterflies and flowers, was entirely unlike the plaids and traditionally patterned batik sarongs common in central Java.

|

|

| At his home in Kudus, Pa Haji Maksum wears a pelicat sarong. |

I sat down to look through her collection. I noticed that many of these flowered sarongs were signed. She told me that most of her inventory came from Pekalongan, a medium-sized city on the north coast. For a few dollars each, I bought several, choosing the ones with the most distinctively bright yellows, blues, reds and soft pastels. They all used designs with floral borders, birds and butterflies, and one of the sarongs had a patterned background that looked very much like a wall of Delft tile.

These, I thought, seemed more like collector’s items than sleepwear. Later, I found a plainer, pelicat (plaid) sarong in a different part of the market, and an old man showed me several ways to tie it. (See below.)

Then about a year ago, on the western end of Sacramento Street in San Francisco, I discovered Indoarts, a shop that specializes in Indonesian fabrics and artifacts. The owner, Noeleke Klavert, has a collection of rare sarongs and an encyclopedic knowledge of the designs and famous workshops from the early 1930’s. We fell into conversation about the sarongs from Pekalongan. He showed me examples of hokokai, the brightly colored floral style that was developed for the Japanese market during World War II, and a much older, classic diagonal design known as parang rusak that arose in the royal courts of central Java. A few days later, I brought him one of the sarongs that I had bought in Jogjakarta more than a quarter-century earlier. He unfolded it, held it up, turned it around and then closely examined the signature.

|

|

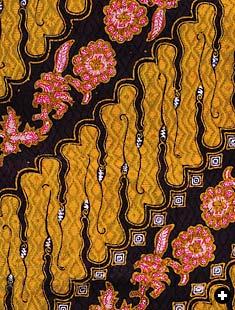

| The kepala (“head”) section of a traditional Javanese pasisir (north-coast) sarong. |

“Oey Soe Tjoen,” he read. “You know who this is, don’t you?”

I didn’t, of course. All that I knew was that in 1975 I had paid $2.50 for it, that it has a small tear, that the colors, executed with both natural and chemical dyes, have not faded and that the design is a classic from the late 1930’s. Klavert told me more: A serious collector would pay from $1800 to $3000 for an Oey Soe Tjoen sarong like mine. He lent me several books on the history of Indonesian sarongs, and three months later I was driving on my way to Pekalongan in hopes of finding the workshop of the late Oey Soe Tjoen.

arongs are the most important articles of clothing in Indonesia, and they are worn by men, women and children. They are simply the most comfortable garments to wear in hot, humid weather. As a general rule, cotton pelicat sarongs, with their woven plaid designs, are the choice for men, while women often wear machine-printed cotton with batik designs. (Batik is a general term that refers to a wax-resist fabric-dyeing technique; tulis is the name of the highest quality freehand batik, whose makers use a hot-wax applicator known as a “canting.” Hand-blocked designs are called cap, and the most common batik fabric is mass-produced.) The most finely executed tulis sarongs can take nine months or more to produce, and these indicate wealth, social rank and style.

arongs are the most important articles of clothing in Indonesia, and they are worn by men, women and children. They are simply the most comfortable garments to wear in hot, humid weather. As a general rule, cotton pelicat sarongs, with their woven plaid designs, are the choice for men, while women often wear machine-printed cotton with batik designs. (Batik is a general term that refers to a wax-resist fabric-dyeing technique; tulis is the name of the highest quality freehand batik, whose makers use a hot-wax applicator known as a “canting.” Hand-blocked designs are called cap, and the most common batik fabric is mass-produced.) The most finely executed tulis sarongs can take nine months or more to produce, and these indicate wealth, social rank and style.

A sarong is made from a length of fabric slightly less than two meters (6' 4") in length by about one meter (39") in width. The far ends are brought together and stitched to create a tube-like garment that is tied at the waist. A typical sarong, whether batik or plaid, has two parts. The kepala (“head”) is a vertical panel that takes up about one-quarter of the fabric. The badan (“body”) fills the remaining area, usually with a repeating pattern that serves to highlight the kepala.

|

|

| Bolts of machine-woven plaid fabric known as pelicat are ready to be cut and stitched at the Gajah Duduk factory. |

|

|

|

| A billboard in Pekalongan advertises Gajah Duduk (“Seated Elephant”) brand sarongs. |

|

|

|

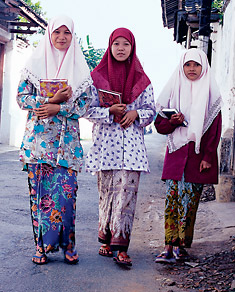

| Schoolgirls in the town of Kudus walk home wearing machine-printed batik sarongs. |

Formal batik sarongs, printed on high-quality cambric cotton fabric, are worn by both men and women at weddings, circumcision ceremonies, funerals or other important occasions. A formal sarong is always carefully tied full length. The more utilitarian batik sarongs, known as batik kampong (“village batik”), or sarong sehari-hari (a generic term for everyday sarongs such as pelicats), are worn as casual dress at home. A sarong mandi is a bath sarong, generally made of lighter, quick-drying fabric. These sarongs are casually tied at the waist by men or under the arms by women. Men often shorten the length of an everyday sarong by turning down the hem at the top before tying it. A sarong shortened in this fashion allows for comfort in hot weather as well as greater ease of movement while working. A sarong permits good air circulation around the legs and is thus far more comfortable to wear than long pants. In terms of practicality, the only drawback to wearing a sarong has to do with the fact that it must be constantly tied and re-tied throughout the day.

After nearly three decades of traveling and living in Southeast Asia, I have concluded that the sarong is one of the world’s most versatile garments: By tying together the four corners, it becomes a carrying sack. Turned sideways, gathered at the top and hung from a flexible sapling or a hook on a spring, it forms a gently bouncing cradle-like sling for a sleeping baby. In a similar fashion, the sarong can be knotted to a shorter length, then draped over a shoulder and hung at the opposite hip to form a baby carrier. To create a private changing room at home or when bathing in public, the upper edge of the sarong is held in the teeth while the tube of fabric encircles the body with a privacy screen. Worn over the shoulders and head, a sarong functions as a wind-breaker; wrapped around the neck, it becomes a muffler or scarf. Men, women and children use sarongs as pajamas or, when necessary, as a lightweight, open-footed sleeping bag.

ecause fabric is not as long-lasting as stone or even wood, it is impossible to establish with any degree of certainty when sarongs were first used in Java, but one of the earliest historical records of sarongs can be seen on the bas relief stone figures of the temple complex at Borobudur, built in the eighth and ninth centuries of our era in central Java.

ecause fabric is not as long-lasting as stone or even wood, it is impossible to establish with any degree of certainty when sarongs were first used in Java, but one of the earliest historical records of sarongs can be seen on the bas relief stone figures of the temple complex at Borobudur, built in the eighth and ninth centuries of our era in central Java.

North from there, the entire north coast of Java is known as the pasisir, an Indonesian term meaning “coastal area.” Trade between ports of this coast and India and China started as early as the fifth century and increased greatly from about 1400, when Arab Muslim traders from Gujarat and the Coromandel coast of India, as well as Chinese ones, set up more permanent trading ports. Like the nearby Straits of Malacca, the north coast of Java was ideally positioned to take part in the spice trade that connected the Indonesian archipelago with the Middle East, India, China and Europe.

|

|

| Detail of a freehand tulis sarong made by Ibu Djogo Pertiwi of Imogiri Village. |

Starting in the early 1500’s, the spice trade attracted the Portuguese, Dutch and, eventually, the British East India Company. There were seven principal pasisir trading ports: Cirebon, Pekalongan, Semarang, Demak (the birthplace of Javanese Islam in the late 15th century), Lasem, Gresik and Surabaya. In their markets, fine batik sarongs from central Java as well as pelicat sarongs—originally imported from India—were exchanged for cloves, nutmeg and other spices from the Moluccas. The pelicat sarongs were very popular, and they quickly caught on as everyday wear for the seagoing traders of the time. According to the venerable Hobson Jobson: The Anglo-Indian Dictionary, the pelicat sarong gets its name from Pulicat, the first Dutch possession on the Coromandel coast of South India, just north of Madras, from where a Dutch cotton factory exported both checked and plaid sarongs to the pasisir and other points in Southeast Asia as early as 1611.

The intermingling of cultures along the pasisir eventually led to distinctively regional styles of batik sarongs that flourished from approximately 1800 until the mid-1940’s. Fusions of Islamic, Javanese, Chinese, Dutch and Indo-European designs, pasisir sarongs used color more freely as well as new motifs, layouts and patterns—including European wallpaper designs—all of which stood in contrast to the more formal and subdued classical patterns. The center of pasisir batik sarongs was Pekalongan. By the 1880’s, the workshops of Indo-Europeans such as Eliza Van Zuylen were experimenting with new aniline chemical dyes in combination with traditional vegetable dyes; these latest sarongs were traded throughout Southeast Asia and eventually became part of an Indo-Malay-Chinese style.

y the time I arrived in Jogjakarta, I had a long list of sarong makers that I wanted to visit. One of the first was Apip’s Batik, a high-end family operation on the outskirts of the city. Apip and his workers specialize in fashionable batik designs on silk. I looked at this beautiful work briefly, but my primary interest lay in his collection of traditional freehand batik tulis sarongs. I was not disappointed: An entire room of his home was lined with glass-faced cabinets that held thousands of sarongs. For more than an hour, I learned about such little-known designs such as tiga negiri (“three countries”), and within minutes of hearing about it, one of Apip’s assistants would bring me several examples to inspect. While he was showing me a particularly fine Oey Soe Tjoen sarong, I asked Apip whether the old workshop was still open. Apip knew the village near Pekalongan where Oey Soe Tjoen had originally worked, but he didn’t have a phone number nor a street address, and he was not sure if the family were still in business.

y the time I arrived in Jogjakarta, I had a long list of sarong makers that I wanted to visit. One of the first was Apip’s Batik, a high-end family operation on the outskirts of the city. Apip and his workers specialize in fashionable batik designs on silk. I looked at this beautiful work briefly, but my primary interest lay in his collection of traditional freehand batik tulis sarongs. I was not disappointed: An entire room of his home was lined with glass-faced cabinets that held thousands of sarongs. For more than an hour, I learned about such little-known designs such as tiga negiri (“three countries”), and within minutes of hearing about it, one of Apip’s assistants would bring me several examples to inspect. While he was showing me a particularly fine Oey Soe Tjoen sarong, I asked Apip whether the old workshop was still open. Apip knew the village near Pekalongan where Oey Soe Tjoen had originally worked, but he didn’t have a phone number nor a street address, and he was not sure if the family were still in business.

|

|

| An artisan applies a hot wax pattern using a hand block at Apip’s Batik in Jogjakarta; other blocks hang on the louvered wall. |

|

|

|

| A master at batik tulis sarongs, Ibu Djogo Pertiwi, 96, applies wax using a pencil-like canting. |

|

|

|

| To complete the manufacture of this Oey Soe Tjoen sarong, the two ends will be stitched together to form a tube. |

|

|

|

| A pattern from Apip’s Batik. |

The following afternoon I met an expert in fine batik sarongs, Pa Sumarwoto, or Pa Woto, as he is more commonly known. (In Indonesian, “Pa” is an honorific meaning “father”; its female counterpart is “Ibu.”) He suggested that to know sarongs best, we drive first to the northern edge of town to visit a madrasa where we could photograph boys wearing the pelicat style.

That afternoon we met with the director of the madrasa, who led us to the mosque where the boys, dressed in a beautiful assortment of pelicat sarongs, were seated in pairs, face to face, as they took turns reciting passages of the Qur’an. The recitation went on for nearly two hours and during that time the boys took hardly any notice of me or my camera.

The next day, Pa Woto took me to Imogiri Village to visit Ibu Djogo Pertiwi, a 96-year-old batik master. Ibu Pertiwi has been practicing batik since she was 13. She still works every day, but she also employs approximately 100 women who work from home on a piecework basis. Ibu Pertiwi knows most of the intricate designs by heart, and she no longer needs a printed master pattern to trace from. Working with sure strokes of her canting, she started drawing a complicated design without any sort of guide or measurement. She began in one corner of the fabric and then steadily filled in the intricate pattern until she reached the far end. During the process she paused only briefly to refill her canting with hot wax. When I asked if she ever made mistakes, she told me that after 83 years of experience, mistakes were infrequent.

On the far edge of Imogiri Village, we visited an older couple by the names of Pa and Ibu Muchtar. Ibu Muchtar wasn’t working that day, but she pulled out several sarongs that were at different stages of completion. She specializes in expensive, fine batik sarongs for weddings. Each pattern had a name, such as sido luhur, “will be respected.”

After looking through Ibu Muchtar’s collection, her good-natured husband obliged my request to photograph him tying a plaid sarong. This request was somewhat similar to asking a stranger to demonstrate getting dressed in pajamas, so ordinary were the actions for him. Then we all sat down for tea, coconut-sugar sweets and stories about their recent pilgrimage to Makkah. Before we left, Pa Muchtar brought us two very small cups with a few sips of water in each: a souvenir from Makkah’s holy spring, Zamzam.

he following day, a driver took us north along winding, two-lane roads through terraced rice fields and coffee plantations in the central mountains. We arrived in Pekalongan late in the afternoon. As we eased our way into the city center through a crush of trucks, buses, private cars, bicycles, pedal cabs and pedestrians, I noticed a billboard that read: “Gajah Duduk.” Seeing these words, I could hardly contain my excitement. Gajah Duduk may mean “seated elephant,” but it is also the brand name of my favorite pelicat sarongs. I was taken by surprise because I had had no idea that the company was located in Pekalongan.

he following day, a driver took us north along winding, two-lane roads through terraced rice fields and coffee plantations in the central mountains. We arrived in Pekalongan late in the afternoon. As we eased our way into the city center through a crush of trucks, buses, private cars, bicycles, pedal cabs and pedestrians, I noticed a billboard that read: “Gajah Duduk.” Seeing these words, I could hardly contain my excitement. Gajah Duduk may mean “seated elephant,” but it is also the brand name of my favorite pelicat sarongs. I was taken by surprise because I had had no idea that the company was located in Pekalongan.

We decided to set aside our quest for Oey Soe Tjoen temporarily, and the next morning it took Pa Woto and me the better part of an hour to explain ourselves to the security guard and public relations office of the Gajah Duduk sarong factory. By mid-morning we entered a textile mill illuminated from all sides by natural light, where thousands of power looms were pounding out miles of pelicat sarongs, a full seven million every year. The sharp clack of flying shuttles and the pounding of the weft threads were deafening, and the humidity and temperature stifling.

Each loom was making a continuous piece of sarong fabric approximately 183 meters (nearly 600') long. After sizing the fabric with a dilute solution of tapioca, drying it, ironing it and checking it for flaws, workers cut the fabric by hand, with scissors, into individual lengths measuring 130 centimeters by 200 centimeters (51" by 78"). These pieces were then stitched into sarongs in a vast room full of young women. The man who guided us through the factory explained that pelicat sarongs had been mass-produced in Pekalongan since the middle of the 19th century. It was also his opinion that the local pelicat industry had helped to set the scene for Pekalongan’s rise as a producer and exporter of the much finer batik sarongs.

|

|

| As with a turban, a ghutra, a sari or a shawl, there is a fine art to tying a sarong. Men and women fasten them differently and there are regional styles that, in combination with specific designs, will identify where a person comes from and what his or her social class is. Throughout Southeast Asia, there is great importance placed on getting the hem perfectly straight and making sure that the kepala is properly centered either in the front or back. Women often fold a sarong in such a way as to display the entire kepala, while men frequently conceal this section with two overlapping front folds. Beyond these aesthetic considerations, it is essential to carefully position the spacing and angles of the front folds to allow for ease of walking. The most common and useful tying technique is a side-to-side, overlapping front fold with a flat roll, as shown here. |

a Woto and I eventually found our way to the rambling neighborhood of Kedungwuni. We drove by the workshop of Oey Soe Tjoen several times before Pa Woto finally saw a nondescript storefront with a small, hand-painted sign that read simply “Batik Art.” Glancing up and down the street, I found it hard to believe that I had just traveled halfway around the world to visit a workshop in this inauspicious place.

a Woto and I eventually found our way to the rambling neighborhood of Kedungwuni. We drove by the workshop of Oey Soe Tjoen several times before Pa Woto finally saw a nondescript storefront with a small, hand-painted sign that read simply “Batik Art.” Glancing up and down the street, I found it hard to believe that I had just traveled halfway around the world to visit a workshop in this inauspicious place.

We pounded on the front door for several minutes and eventually a woman unlocked the door and invited us in. Oey Soe Tjoen’s middle-aged son, Pak Muljadi Widjaja, soon joined us. Oey Soe Tjoen had died years earlier, but Pak Muljadi and his wife were carrying on the business and maintaining the same high standard of work. Batik Art is probably one of the last master batik workshops in Indonesia.

|

|

| Design on a silk sarong from Apip’s Batik. |

We were served tea. We sat in the sparsely lit reception area, where we looked at old pattern books. The son talked about the history of the pasisir sarong style, and he showed us original pencil sketches that his father had copied or adapted from Dutch postcards and horticultural books from the 1930’s. Chinese designs included peacocks and leaves, as well as Feng-Huan, the mythical phoenix bird. But as interesting as this background information was, what I really wanted to do was visit the workshop in the back.

The sweet smell of beeswax and dye permeated the place. After more tea and more talk, we were led down a narrow hallway toward the back of the building. We passed through a storage room, then the dyeing section. We arrived at the edge of a circle of young women. Each was seated on a low stool as she worked on her piece of fabric. With delicate strokes and holding the tool like a pen, the women used very finely tipped cantings to apply hot wax to the cloth, which was supported on a hardwood frame.

Natural light flooded the tall workroom from two sides. The corrugated metal roof creaked in the midday heat, roosters crowed, cauldrons of hot water that kept the wax liquid sent up billows of steam, and the gentle buzz of conversation gave me a profound sense of timelessness. The astonishing detail of the handwork was mesmerizing. Within minutes I understood why the Oey Soe Tjoen workshop had a reputation for batik tulis of the highest quality. After our mind-pounding tour of the Gajah Duduk factory, it was reassuring to know that a small workshop, specializing in highly skilled, labor-intensive handwork, could still thrive.

The canting, with its reservoir of liquid beeswax and its fine applicator, works like a cross between an old-fashioned oil can and an airbrush. The women dipped their cantings in the hot beeswax to refill the reservoirs, blew on the tips to stimulate the flow, and then leaned forward to continue applying row upon row of thin lines, squiggles and barely noticeable wax dots. Their concentration was intense, and the entire process of waxing would be repeated for each new color. One woman was working on a tiny portion of a voluptuous peony in full bloom, and I couldn’t help wondering how much time it would take her to complete one petal or a single flower. From what I had been told, I knew the entire process of producing an Oey Soe Tjoen sarong could take anywhere from six to nine months.

|

|

| The Oey Soe Tjoen workshop in Pekalongan is home to some of the finest batik tulis artisans in Indonesia; each sarong takes as long as six to nine months to complete. |

The Oey Soe Tjoen workshop is a modern survivor: It saw the Japanese occupation and the struggle for independence from Dutch rule following World War II, and it has dodged the greater threat of cheap, machine-printed sarongs. Experts still claim that Oey Soe Tjoen sarongs are the finest produced in Java, and perhaps in all of Indonesia.

Before I left, I asked if I could buy a sarong; I was told that there was a nine-month backlog of orders. The price for a new sarong with one of their traditional flower, bird and butterfly designs was around $450. They had several older pieces for sale, but I didn’t ask the prices. It seemed unlikely that I would be able to find anything as reasonably priced as the Oey Soe Tjoen for which I had paid $2.50 30 years earlier.

Driving back to Jogjakarta, I looked at people in the villages and at work in the fields. A few were dressed in shorts and T-shirts, but many still wore everyday cotton sarongs tied so the bottom hem reached just below their knees. In the city, I caught sight of people on the street wearing sarongs: an older man riding a bicycle, a women carrying a baby on her hip, schoolgirls returning home and groups of boys walking to the mosque. I saw pelicats and mass-produced floral-print batik sarongs—nothing of significant value, but every time I spotted one, I thought about the history of this garment and how sarongs seemed so comfortable, dignified and timeless.

|

Eric Hansen is a writer and photographer who lives in San Francisco and specializes in the traditional cultures of Southeast Asia and the Middle East. His most recent book is Orchid Fever (Vintage Books); he can be reached at ekhansen@ix.netcom.com. |

|

|