Written and Photographed by Michael R. Hayward

|

|

single species of intensely perfumed, delicate pink flower annually transforms the rural communities of al-Hada (“Tranquility”) and al-Shafa (“The Edge”) into fragrant, roseate splendors. For three centuries, the oil-rich, 30-petal damask rose (Rosa x Damascena trigintipetala) has been cultivated here and processed into precious attar of roses and its popular—and even older—counterpart, rose water.

single species of intensely perfumed, delicate pink flower annually transforms the rural communities of al-Hada (“Tranquility”) and al-Shafa (“The Edge”) into fragrant, roseate splendors. For three centuries, the oil-rich, 30-petal damask rose (Rosa x Damascena trigintipetala) has been cultivated here and processed into precious attar of roses and its popular—and even older—counterpart, rose water.

Blessed with a climate that makes it a refuge from the heat of nearby Jiddah and Makkah, the highland haven of Taif is one of Saudi Arabia’s fruitbaskets, as well as a popular summer resort. West of the city, the land rises above 2000 meters, and it is here that favorable temperatures, plentiful groundwater, well-established irrigation systems and fine topsoil have combined to earn the region the name “Arabia’s Rose,” ever since roses began to be cultivated here in the Ottoman era.

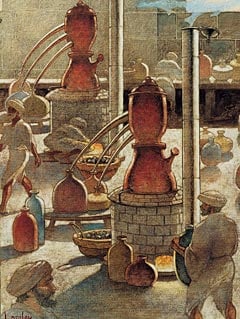

The word attar, which is today a synonym for rose oil, comes from the Arabic ‘itr, meaning “perfume” or “essence.” The first description of the distillation of rose petals was written by the ninth-century philosopher al-Kindi, and more sophisticated equipment was described in the 10th century by al-Razi; one of the earliest centers of rose-water production was in southern Persia. Later, in the 13th century, rose water was produced widely in Syria, and the name of the oil-bearing rose genus Damascena may trace its origins to the city of Damascus. But true attar—rose oil as we know it today—was not produced until the late 16th century, when the double-distillation technique was developed.

No one is certain how the 30-petal damask rose first came to Taif. The impulse for its cultivation, however, assuredly lay in Taif’s proximity to Makkah. That the rose of Taif is virtually identical to the famous Bulgarian “kazanlık” strain suggests that Taif’s roses may have been transplanted from the Balkans by the Ottoman Turks, who occupied that area from the mid-14th century and the Hijaz from the 16th century. However, the kazanlık rose—its Turkish name means “suitable for the [distiller’s] kettle”—has its own roots in the Persian rose plantations around Shiraz and Kashan, which in turn supplied fields in Syria. A legend among the growers of al-Hada says that the flower originally came from India.

|

| Throughout the April rose harvest, pickers rise early

to pluck the blossoms just after they open and before the day’s warmth evaporates their fragrant and volatile oil. |

|

Today, Taif’s production, though high in quality, is modest when compared to the quantities produced by larger, export-oriented operations in Turkey, Bulgaria, Russia, China, India, Morocco and Iran. But the market is not oversupplied, for, now as always, attar is painstakingly obtained, and both its potency and its price remain so high that a gift of this precious oil is one of the highest compliments that can be paid to anyone.

In the early days, up to 200 years ago, Taif’s rose petals were collected and sealed into sacks for transport by camel roughly 65 kilometers down to the holy city of Makkah. There, Indian pharmacists distilled attar from them, using a process not unlike that used today. These artisans became masters of one particularly fine type of attar that they produced by infusing rose distillate into sandalwood oil, resulting in a blend with refreshing floral and woody notes. Interestingly, this blend can still be found in India, though it is now rare in the Saudi Arabian market.

About two centuries ago, the distillers brought their craft to Taif itself. Here, closer to the rose fields, the manufacture of rose oil was more efficient, because the volatile rose oils evaporate rapidly from harvested petals. Soon after the establishment of these distilleries, Taif rose oil began to win acclaim from all over the Muslim world. Any pilgrim who could afford it bought at least one vial—called a tolah for the weight of its contents—of the celebrated perfume as a souvenir of the Hajj. Pilgrims traveling overland from the east would often take the route through Taif specifically to purchase rose oil. To the present day, Taif rose oil is the variety preferred by the authorities of Makkah, where attar is used to perfume the the so-called Yemeni Corner of the holy Ka’bah in Makkah’s Grand Mosque.

But while a well-stoppered bottle of attar endures for years, perhaps indefinitely, the glory of Taif’s roses themselves is ephemeral. Their flowering lasts only the month of April, and each day’s harvesting begins at dawn and is over by 7:00 a.m. But during this harvest, open any window in al-Hada or al-Shafa and savor the fragrance that permeates the still mountain air at daybreak. From any vantage point, vistas of pink unfold as the rising sun spills over the ridges.

|

| Roomfuls of blossoms

are distilled to produce minute quantities of precious attar, or rose oil,

the most widely used ingredient in the world’s commercial perfumes. |

For the pickers, there is no time to lose. Down in the fields, the light of the new day illuminates the early risers, baskets in hand, some still clad in nightshirts.

Collect an empty basket and join the bands of laborers, for rose growers on the region’s nearly 2000 family-owned farms now need all the help they can muster. The pink, cupped blooms unfold only at dawn, and as the sun moves higher, the oils evaporate until, by midday, unpicked blossoms contain only about half the oil they had at daybreak.

|

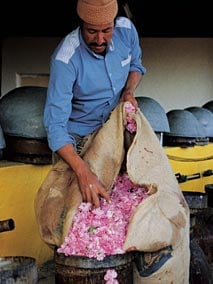

| Above: Loading the still promptly after harvest. Below: The two-part distillation process begins in a copper still topped with an alembic whose spout guides the distillate through a cooling tank, a technique developed at least a thousand years ago. |

|

At the peak of the crop, roughly the third week of April, an established bush, which can be head-high, could be topped with up to 200 roses each morning. A fully mature bush, perhaps 15 to 20 years old, heavily manured and judiciously pruned back each December, can produce more than 3000 roses during the season.

Once the picking basket is brimming with blossoms, damp and sparkling with dew, join the procession to one of the nearby distilleries. In al-Hada, one is owned by the al-Ghashmari clan who, passionately fond of perfume and flowers, still practice the craft of two-step distillation as it has been done for centuries.

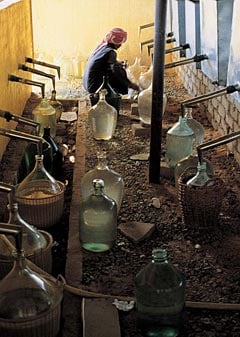

Attar and rose water are produced using 120-liter tin-lined copper boilers. Today they are heated by gas rather than by wood or, as they sometimes were, by smokeless and odorless cakes of camel dung. Into the copper boilers are poured about 50 liters of water and roughly 10,000 rose blossoms. This simple mixture is allowed to simmer gently for up to six hours. The steam is collected by an alembic, a mushroom-shaped helmet that fits tightly on the boiler and has a tube that angles down from the top. This tube directs the steam through a zinc cooling tank filled with tepid water. There, the distillate condenses and runs down into a large glass carboy, where it begins to separate into rose water and attar.

But the yield of attar from this first distillation is low, as most of the volatile oil is still dispersed in the rose water, which is known as al-arus, or “the bride.” The arus must be redistilled, a process called cohobation. There are two types of cohobation: arus can either be poured onto a batch of freshly picked flowers—from which it dissolves a higher proportion of the volatile oils than hot water can—and then redistilled with care, avoiding excessive heat, or it can be distilled a second time on its own, again very slowly. Either method produces an enriched rose-water condensate called al-thino or “second cut.” Once cohobation is complete and the product has cooled, there is great excitement as the richly-perfumed globules of attar coalesce and rise to the surface of the rose water. From there they are decanted. Only by the added effort and expense of cohobation can the highest yield of oil be obtained.

|

| Rose water, product of the first round of distillation, can flavor tea if fresh roses are not at hand. |

The freshly distilled attar is then allowed to stand for several days to permit impurities and colloidal matter to precipitate and the remaining water to separate. The clean essence is then carefully syringed away and stored in vials, each of which holds one tolah, or 11.7 grams. On the market, the price of each tolah will vary with the season and with local demand, but it will usually sell for between 2000 and 3000 Saudi riyals—$530 to $800.

This price is more understandable when one considers that it takes between 10,000 and 15,000 hand-picked roses to manufacture a tolah of attar, depending upon climatic conditions. Well-defined night-to-day temperature fluctuations, relative humidity above 50 percent, calm air and clear skies all lead to the formation of early-morning dews which encourage the rose’s buildup of ample, high-quality oil. Because these conditions are sufficiently consistent in Taif, the quintessential aroma of Taif rose oil is warm, highly tenacious, immensely rich, deeply rose-floral—truly redolent of damask roses—and embellished with spicy and occasionally honey-like notes. Its qualities easily match—some say exceed—those of rival products from other lands.

|

| Some of the 60 stills in the al-Qadhi factory. |

By contrast, the highly regarded rose essence from southern France is liberated by an alcohol-based process. It expresses its essence more consistently and completely, but this softer-toned absolute lacks the prominent, spicy topnote offered by traditionally hydrodistilled attar of roses.

For its part, rose water is not merely a by-product. It is in fact the reason that roses were first distilled at all, and today it is a popular, relatively inexpensive product sold for medicinal, culinary and celebratory purposes. It enjoys wide popularity throughout the Middle East, and is a must in every kitchen—though Taifi rose water specifically is rarely found even in Riyadh or Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. Tradition maintains that arus rose water is beneficial for the heart and stomach. This primary condensate is particularly sought-after during Ramadan, when it is used in preparing the fast-breaking meal, and during the ‘Id al-Fitr that follows Ramadan, when it is often employed as a flavoring in custards, jellies, sweets and other desserts. Rose water offers a way to refine the socially ubiquitous glass of tea, and it is now often offered as a healthful caffeine-free “white coffee.” It also finds a place in the preparation of traditional cosmetics. For example, the black kohl (powdered antimony sulfide) that is used like eyeliner throughout the Arabian Peninsula is often mixed into an applicable paste by adding rose water, which is said to aid impaired vision and combat eye infections.

|

| Some of the 60 stills in the al-Qadhi factory. |

Hand-held rose-water sprinklers, traditionally made with long straight necks and bulbous bottoms, have a time-honored role in festivities in much of the Muslim world. To mark the end of a wedding feast, rose water is sprinkled on the hands and faces of guests. Aesthetic appreciation and commercial demand have encouraged silversmiths and other artisans to develop exceptionally beautiful sprinklers, examples of which can be found in museums throughout the Arabian Gulf region. In the home, a precious rose-water sprinkler is a symbol of hospitality and, incidentally, a demonstration of social standing and affluence.

Within Taif’s rose industry, there is a spirit of competition between the districts of al-Hada and al-Shafa, and local connoisseurs can debate endlessly the relative merits of attar produced from the roses of the two areas. The majority of al-Hada’s growers cultivate and process their crop individually; the bulk of the al-Shafa harvest, however, is trucked to the al-Qadhi family’s Taif factory.

Until recently, the al-Qadhi establishment was located amid a maze of alleyways in the heart of Taif’s old suq. For two centuries, the family had operated their perfume factory there, and it was reputed to be the oldest functioning perfumery in Saudi Arabia. Following the 1990 harvest, however, the al-Qadhis packed up their stills and moved to the al-Salamah district, on the periphery of the suq. Nearly eight years later, the thick stone walls of the old factory are still suffused with fragrant “essence of Taif.”

|

| A Bahraini shopkeeper daubs a gentleman’s blend on the top of a customer’s ghutra in the traditional fashion. |

Since the move, the company has doubled its capacity with 30 new, shiny aluminum vats. Together with their traditional copper ones, still in use, the al-Qadhis now boast 60 anbiqs, or distillation units. However, Hasan al-Qadhi, who directs the family business, admits that the new boilers do not perform as well as the traditional copper ones, the oldest of which dates back to 1816.

Nonetheless, under favorable conditions a staggering 35 million al-Shafa roses are distilled there each season, and they surrender 25 kilograms of attar. Including the production from al-Hada, Taif perfumers thus produce an annual bounty of around 75 kilograms of pure oil each year—one twenty-fourth as much as Turkey does.

Naturally, they also produce millions of cooked flower heads. Most of this mash is sold to cattle farmers, who feed the spent flowers to their cows. In return for this delicacy, the cows produce a mildly rose-flavored milk! The pulp residue is also used as a fertilizer and an organic mulch.

For al-Hada’s part, entrepreneurs there have recently pooled their resources and invested in modern stainless-steel hydrodistillation equipment imported from Grasse, in southern France, the world center of perfume production. Over several seasons, this state-of-the-art equipment has delivered a superlative attar of consistent nuance and without off-odors, though at the cost of diminished quantity when compared to the traditional stills. This innovation in al-Hada signals a break with the past, and it seems possible that precious Taifi rose water may become more widely available. An enduring scent that breathes of long tradition, the essence of Taif is likely to remain an evocative and timeless fragrance.

|

| Several of the Taif-area rose distilleries market their own brands of rose water, shown here with a traditionally shaped hand-held silver sprinkler. |

|

In the eighth century BC , Homer described how the goddess Aphrodite anointed Hector’s corpse with rose oil. In our era, the first-century Greek physician and pharmacologist Dioscorides, in his De Materia Medica, mentioned a rose product called rhodium, from the Greek word rhodon, meaning “rose.” But when classical writers spoke of “rose oil” they undoubtedly referred not to the attar we know today, but to fatty oils heavily perfumed with rose by the technique called “enfleurage.”

|

BOB LAPSLEY |

As used by the ancient Egyptians, enfleurage involved steeping flower petals in purified animal fat and replacing them as soon as their perfumes had penetrated it. (A similar process, called “maceration,” uses hot oil instead of fat.) The perfumed fat was used to make a scented ointment, or unguent. These fragrant balms became known as “pomades,” a term which includes aromatic fatty oils employed both for remedial and for aesthetic purposes.

Egyptian wall paintings show cones or balls of pomade atop the heads of Egyptian ladies. Today, small quantities of pomade are still manufactured by virtually the same methods in the region of Grasse, in France.

Rose water was distilled by the Arabs at least as early as the ninth century, when al-Kindi wrote his Kitab Kimya’ al-‘Itr wa al-Tas‘idat (Book of Perfume Chemistry and Distillation), but the earliest source that claims to document the origin of attar as a derivative of rose water comes from India. The 17th-century Mughal emperor Jahangir, in his memoirs, credits the discovery of attar of roses to his mother-in-law, Salima Sultan Begum. “This ‘itr is a discovery which was made during my reign by the mother of Nur Jahan Begum,” he writes. “When she was making rose water, a scum formed on the surface of the dishes into which the hot rose water was poured from the jugs. She collected this scum little by little; when much rose water was obtained a considerable quantity of the scum was collected. It is of such strength in perfume that if one drop be rubbed on the palm of the hand it scents a whole assembly and it seems as if many red rosebuds had bloomed at once. There is no other scent of equal excellence to it. It restores hearts that have gone and brings back withered souls. In reward for that invention, I presented a string of pearls to the inventor. Salima Sultan Begum—may the light of God be upon her tomb—gave this oil the name ‘itr-i-Jahangiri.”

We have no such documentation on the origins of cohobation, the technique that is the key to maximizing the yield of attar. There are no certain reports of its use by the early Muslim alchemists, no mention in literature, and no description of it in any travel account earlier than the second half of the 16th century. We have only one clue, from etymology, that the technique may be of Arab origin. The word kohob was used by Paracelsus to mean “repetition,” and that word may derive from Arabic ka‘aba, “to repeat [an action].”

My belief is that cohobation was developed independently in Europe, India and the Arab world, probably—in the case of Europe—in the mid-16th century: A European source dated 1574 names Geronimo Rossi of Ravenna as the first to accomplish cohobation, and oleum rosarum distillatum—distilled oil of roses—appears in German apothecaries’ price lists of the 1580’s.

There is also a theory that places the invention in Bulgaria, an important rose-growing country for the past 350 or 400 years. Its adherents point out that multiple distillation was already a well-understood technology in Bulgaria by the time the Ottomans brought the oil-bearing rose there in the first half of the 17th century. To the north of what is now known as the Rose Valley, in the villages around the towns of Gabrovo, Sevlievo and Troyan, plum brandy had been produced for years, its strength and quality increased by repeated distillation. The Ottomans discouraged the production of alcohol, but the distilleries, and the technique of cohobation, were easily adapted to the production of attar of roses.

In my opinion, the world’s most beautiful attars today come from Bulgaria, Saudi Arabia and Russia, each with a subtle yet distinctive nuance: of spice, honey and softer-hued tonalities respectively. To the many successive generations of inventors who made the production of such beauty possible, we owe our thanks. |

|

|

Michael R. Hayward is a dental surgeon who works in Saudi Arabia and has a special interest in perfumes. He lives in Dhahran. |

—Adapted from the book Saudi Aramco and Its World (1995)