n 2000, Okolo Rashid was as excited as most other Mississippians at the prospect of the upcoming blockbuster exhibition “The Majesty of Spain: Royal Collections from the Museo del Prado and Patrimonio Nacional.” The third in a series of biannual international exhibitions hosted by Jackson’s Mississippi Arts Pavilion, “Majesty” was expected to attract half a million visitors—including King Juan Carlos and Queen Sophia of Spain.

n 2000, Okolo Rashid was as excited as most other Mississippians at the prospect of the upcoming blockbuster exhibition “The Majesty of Spain: Royal Collections from the Museo del Prado and Patrimonio Nacional.” The third in a series of biannual international exhibitions hosted by Jackson’s Mississippi Arts Pavilion, “Majesty” was expected to attract half a million visitors—including King Juan Carlos and Queen Sophia of Spain.

A devout and well-read Muslim, Rashid knew that one of Spain’s most illustrious periods had been the roughly 800 years of Muslim rule in Al-Andalus, the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula. It was a time of productive and mostly peaceful coexistence among Spain’s Muslims, Christians and Jews, as well as among the many mixes of nationalities. As a leader in one of Jackson’s two mosques, Rashid welcomed the Spanish exhibition as an opportunity for showcasing the positive legacy of her faith.

But she had a surprise coming. “I was looking at all the marketing materials,” Rashid remembers, “and I realized they were going to leave out the important contributions of Muslims.”

|

| At first, “everyone we talked to said we were crazy, that it couldn’t be done.” |

“We’re talking about using history and culture to give you dignity and purpose.” |

Rashid is well-known and well-connected in Jackson, having spent more than 20 years in inner-city community development, organizing and historic preservation. She contacted people in touch with the “Majesty” organizers and was told that she was correct: There would indeed be no mention of the Islamic centuries in the exhibition. “The emphasis was to be European,” she was told.

Rashid was not, she says, “a museum person.” But faced with this significant gap in the coming exhibition, she conceived the idea of a companion exhibit to “Majesty,” one that would focus on the omitted material. She approached her mosque, the Masjid Muhammad, with the idea. The mosque’s economic development board decided to take it on, led by Rashid and the committee chair, Emad Al-Turk. The problem was, they only had five months.

“Everyone we talked to said we were crazy, that it couldn’t be done, that these projects take a couple of years to develop,” says Al-Turk, whose roots are Palestinian.

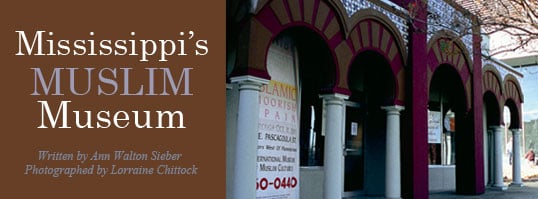

But as a longtime local businessman, as chief operating officer of a large engineering firm, and with decades of experience with interfaith nonprofit organizations, Al-Turk knew how to transform drawings on paper napkins into multistory buildings. The mosque leased a squat, dank, dilapidated building the size of a small house strategically located a block away from the Arts Pavilion and spent $60,000 to transform it with a façade modeled on the Great Mosque in Cordoba, a mosaic-tile floor and a small theater where an introductory video could be shown. A Moroccan fountain was imported to infuse the space with the sound of flowing water.

To produce the exhibit, Rashid and Al-Turk hired CommArts, a local design studio whose principals put other jobs on hold to meet the idealistic deadline. CommArts recreated a period marketplace, or suq, and a diminutive mosque with a 200-year-old minbar (pulpit), a mihrab (prayer niche) and a lofty, 200-year-old door painted with calligraphic motifs. By the time the job was done, mounting the companion exhibition cost $250,000 —more than two-thirds of which came from the mosque community—as well as the same amount again in materials and other donations in kind from the congregation, other religious and cultural institutions, businesses, and local and state governments.

“The Majesty of Spain” opened on March 15, 2001; “Islamic Moorish Spain: Its Legacy to Europe and the West” opened exactly one month later.

“The focus of Muslim Spain is very germane to humanities studies because it’s a case study of a tolerant society of high achievement and reciprocal scholarship among Christians, Jews and Muslims,” says Steve Smith, a professor of religious studies at Millsaps College, one of the several educational institutions aligned with the museum.

More than 30,000 people visited “Islamic Moorish Spain” that year, and half of them were students. And then there came 9/11, which brought a dramatically heightened sense of the need for education about Muslim culture—and also brought a brick, delivered through the museum’s storefront window two nights after the attacks. Instead of discouraging the exhibition’s organizers, the incident elicited support for them from civic leaders and the community.

Rashid and Al-Turk decided then to make their onetime exhibit into a permanent part of Jackson’s cultural landscape. They purchased the exhibit from the mosque and transferred it to a new nonprofit organization, with Rashid as executive director and Al-Turk as chairman of the board. Thus was founded the International Museum of Muslim Cultures—the first of its kind anywhere in the United States—in Jackson, Mississippi, a city with a population of 180,000.

“It kind of breaks a stereotype,” says William Winter, who served as Mississippi’s governor from 1980 to 1984. Winter later chaired President Bill Clinton’s town meetings on race and founded the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi. “It’s at odds with what the average American would think about Jackson, Mississippi. But the fact that [the museum] is located here says a lot about the old provincial stereotype: It’s not the same stereotype anymore.”

Just as the creators of the International Museum of Muslim Cultures put forth Muslim Al-Andalus as a historical model of intercultural cooperation, they hope the museum itself will also serve as such a model. Already it has forged new alliances across the divide that separates the immigrant Muslim community from African-American Muslims.

Masjid Muhammad was Jackson’s first mosque, founded as an all-Black institution. But times changed, and in 2000 the mosque restructured to reach out to the larger Muslim community, a move led in part by Rashid and her husband, Sababu Rashid. Al-Turk was elected to the mosque’s board of trustees, along with a Pakistani and a Sudanese. This step, says Rashid, laid the groundwork for the museum. “When we practice Islam, each culture brings a different aspect to the broader Islamic community,” says Rashid.

Rashid leads the museum with a genial, easygoing earnestness. (Her surname, which she chose when she embraced Islam in 1976, means “wise.”) She says she’s learned life lessons through Islam, and she teaches these through the museum: the importance of learning, self-empowerment and intercultural connection.

Rashid was one of 15 siblings (only 11 lived) who were raised sharecropping the Mississippi Delta in the harsh times of the 1950’s. “Any Black person around here, you say ‘the Delta’ and they know what you mean,” she says. It was so bad that once, for reasons she was too young to know, her father had to move the family to a new home under cover of darkness. She received little schooling as a young girl because she had to work through harvest time, which often stretched through December. When Rashid could finally enroll in school full-time, she never missed a single day thereafter, from fourth grade until she graduated.

|

| Couches, and a model tea set, lend atmosphere to the exhibit "Islamic Moorish Spain." |

“Once given an opportunity, any individual can learn, can excel,” Rashid says. “That is the whole concept behind Islam. The first revelation to the Prophet Mohammed is, ‘Read!’”

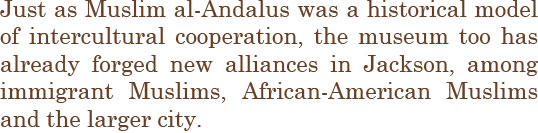

To help local students, the museum has conducted annual teacher-training workshops, and it has influenced the inclusion of Islamic materials in regional colleges and universities. Muslim educator Audrey Shabbas, who has taught tens of thousands of teachers nationwide, has been one of the museum’s consultants from the beginning, and the museum has made use of her curriculum “A Medieval Banquet in the Alhambra Palace.”

“We’re not trying to sell the religion here,” says Rashid. “We’re trying to educate.” But it doesn’t come easy, because neither mainstream Muslims nor African-Americans have much history of museum involvement.

“The focus of the immigrant Muslim community has been on mosques and schools,” Al-Turk says. “Historically they have not been as focused on cultural outreach. If you say you want to build a mosque, they’ll cut you a check right off. If you say you want to build a museum, they say, ‘What the heck do you want to do that for?’”

Even as the museum is devoted to the mainstreaming of Muslim culture, Rashid also sees its mission as part of the larger goal of Black empowerment for which she’s worked all her life. In particular, she hopes the museum’s second show, “The Legacy of Timbuktu: Wonders of the Written Word,” scheduled for this year, will serve this goal. Focus- ing on medieval scholarship in the West African city of Timbuktu, it will showcase manuscripts lent by the Mamma Haidara Memorial Library there that have only recently come to light after families hid them from centuries of colonial governments. In a curatorial coup, the International Museum of Muslim Cultures will be the first us museum to show the manuscripts. The show will also include background on Islam coming to Africa, as well as an unblinking examination of the Saharan slave trade.

Rashid sees in the manuscripts a profound rebuke to the common misconception that Africa had no written cultural history. Quite the opposite, she says: It boasted one of the leading centers of scholarship and learning of its time.

“We’re not just talking about a historical exhibit. We’re talking about using history and culture to give you dignity and purpose to move into the future,” Rashid says. “Studies have shown that if you raise someone up telling them that they came from zero, how are they going to garner the self-esteem to say they are the equal of all other cultures?

“I’d like to see this exhibition promote ideas that would make African-Americans feel more empowered. I don’t think reconciliation can take place until African-Americans feel whole and healed and empowered. For the general public, the exhibition is going to impact historical and cultural literacy. And for non-African-Americans, it’s important to know that not everything they’ve been told all these years is true.”

|

| Jackson health worker Janice Evans called her visit to the museum "my first experience with Muslim culture." |

|

| A qanum (harp), rikk or daff (tambourine) and 'ud (predecessor of the guitar) help highlight the diverse cultural legacy of Al-Andalus. |

To oversee development of the Timbuktu show, the museum has assembled scholars from institutions ranging from the Institute of Global Cultural Studies at Binghamton University in New York to Howard University in Washington, D.C., as well as professional, cultural and political advisors. “The true message we’re dealing with is bringing the other communities into the exhibit,” says Al-Turk. Among local educational institutions, Jackson State University and Tougaloo College, both historically Black institutions, have become extensively involved, as well as Millsaps College and the University of Mississippi.

“Exposure to the wealth of knowledge and the literary and scientific contributions of the Muslim cultures will inspire scholars,” says Beverly Hogan, president of Tougaloo. “Sharing this knowledge with African-Americans will give them a sense of their history and the magnificent contributions of their people. Thus their sense of self and purpose will become stronger, and their place in world affairs will be institutionalized in their minds and actions.”

Recent weeks have brought a setback to future plans— but one that Al-Turk and Rashid hope can be turned into an opportunity: The city has marked the current building for demolition to help make way for the capital’s new convention center. In response, the museum has launched a $15-million capital campaign to raise a building of its own. Meanwhile, the “Timbuktu” exhibition will tour sites around the country: Plans have already been made for it to visit the DuSable Museum of African-American History in Chicago.

“One principle of Islam is that God created all of us equal, teaching respect for all human beings,” says Al-Turk. “We are living in a world today where actual or perceived conflicts between Muslims and the West can only be addressed by peaceful cooperation and education.”

|

Ann Walton Sieber has worked as a writer and editor in Houston for more than 20 years. Her guidebook to vegetarian dining in Houston, VegOut Houston, will be published in 2006 by Gibbs Smith Publishers. |

|

Lorraine Chittock (www.onamissionfromdog.com) is a free-lance photographer and author of Cairo Cats, published by Abbeville Press. |