|

BRITISH LIBRARY

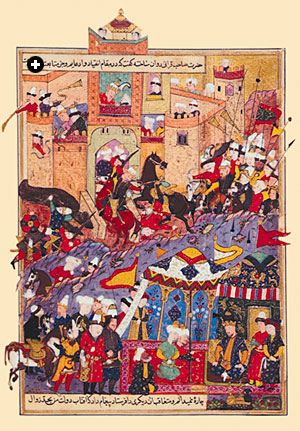

This painting from a 16th-century copy of the Persian historian Mirkhvand’s Rawzat al-Safa (Garden of Purity) shows Timur receiving envoys during his 1370 attack on Balkh, now in northern Afghanistan. It was a far larger embassy that came to him 25 years later, bearing the first of two letters from the Ming court of China that Timur found profoundly insulting.

|

Written by Caroline Stone

t was the year 1404. Timur, who had conquered Asia from Egypt and Syria to the borders of China, was poised to march his armies on the Ming emperor of China. Timur was known in the West as Tamerlane. In his own realms, he was called Sahib-i-Qirani, “Lord of the Fortunate Conjunction of the Planets.” The reason he was prepared to go to war was the way he was referred to in a letter that had arrived eight years earlier, in 1395, carried by an official embassy of more than 1500 men from Hung Wu, the first Ming emperor.

t was the year 1404. Timur, who had conquered Asia from Egypt and Syria to the borders of China, was poised to march his armies on the Ming emperor of China. Timur was known in the West as Tamerlane. In his own realms, he was called Sahib-i-Qirani, “Lord of the Fortunate Conjunction of the Planets.” The reason he was prepared to go to war was the way he was referred to in a letter that had arrived eight years earlier, in 1395, carried by an official embassy of more than 1500 men from Hung Wu, the first Ming emperor.

There had been a number of similar missions in previous years between the Ming court in Khan Baliq (modern Beijing) and that of Timur, in his new capital of Samarkand. Timur’s realms had engaged in a lively trade in horses, highly desirable to the Chinese, and one chronicle put the annual export figure at 1000 head, which Timur found “satisfactory.”

In the provocative letter, however—as was Chinese custom—Timur was addressed as a vassal, his “submission” to Hung Wu was graciously accepted, and he was invited to pay homage to the Dragon Throne and, furthermore, to send tribute. Timur was enraged at the idea that he could be considered anything but sovereign and—to him —the insult was worse coming from a ruler he considered an infidel.

Timur loved war and conquest as much as his Mongol forebears, and war was his response to the insult—but slowly. His sack of Delhi in 1398 and his capture of the Ottoman Sultan Bayazit at Ankara in 1402, as well as other campaigns, preoccupied him over the following years, though he never took his eye off China. When a second letter arrived from Hung Wu inquiring why he had not paid tribute for the past seven years, he mobilized some quarter of a million men and set out for China.

It is unclear just how seriously the Chinese took the threat Timur represented. They could face him with their standing army of more than a million men, and they were long accustomed to trouble on their western border. There is no evidence, however, that they were expecting anything on the scale of the Mongol invasions of 1279, which had overthrown the Chinese Sung Dynasty for the Mongol Yuan, and yet such an overthrow is almost certainly what Timur intended, although he did not issue an explicit threat to the Ming emperor.

|

PAUL LUNDE

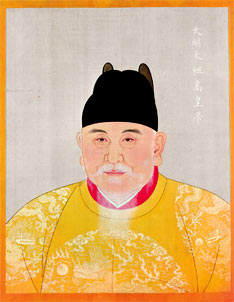

A statue of Timur, known in the West as Tamerlane, stands in the main square of Shakhrisabz, the town where he was born, about 160 kilometers (100 mi) from Samarkand in today’s Uzbekistan. Below: Founder of the Ming Dynasty in 1368, Chu Yüan-chang is commonly known by his regnal title, Hung Wu. He was born a peasant in 1320 near Nanking. |

NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM, TAIPEI / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

NATIONAL PALACE MUSEUM, TAIPEI / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

The two letters followed Chinese protocol, without a scrap of concern for the recipient’s sensibilities, and set in opposition two great empires, threatening perhaps 20 percent of the world’s population with the shockwaves of war.

Then, on February 18, 1405, leading his army toward China, Timur died at Otrar, in today’s Kazakhstan, aged approximately 68.

In China, too, not long after the second letter was sent, the Dragon Throne stood empty with the death of Hung Wu and the country was embroiled in the turmoil of succession.

s so often in history, the conflict was a matter of cross-cultural misunderstanding, a collision of worldviews. The Chinese believed absolutely in their national superiority (even in periods when the ruling class was not actually Chinese); China, they repeatedly claimed, needed nothing from anyone else. Countries beyond the Chinese borders were, by definition, inferior. Ambassadors and other emissaries bringing gifts and trade goods were understood to be vassals offering tribute to a superior power, for which the superior power—noblesse oblige—graciously rewarded them.

s so often in history, the conflict was a matter of cross-cultural misunderstanding, a collision of worldviews. The Chinese believed absolutely in their national superiority (even in periods when the ruling class was not actually Chinese); China, they repeatedly claimed, needed nothing from anyone else. Countries beyond the Chinese borders were, by definition, inferior. Ambassadors and other emissaries bringing gifts and trade goods were understood to be vassals offering tribute to a superior power, for which the superior power—noblesse oblige—graciously rewarded them.

From Samarkand’s point of view, however, the horses and other items sent to China were trade goods politely disguised as diplomatic gifts. Timur’s intention was to encourage good relations and do business. He had no doubt of his personal superiority to any ruler on earth, nor, furthermore, of every ruler’s duty to show submission and obedience to him as a representative of Islam. From its earliest times, the merchant has had a high place in the Muslim social hierarchy—the Prophet Muhammad was himself a merchant—and hence the Timurid ambassadors to China were essentially perceived as being on trade missions, opening up new markets and establishing new relationships along the Silk Roads, as well as finding out what they could of military and practical use about their powerful neighbor.

And so, each convinced of its own self-evident superiority, neither side was the slightest bit interested in the other’s culture or religion.

One early account of these events comes to us from Ruy González de Clavijo, an ambassador to the Timurid court from that of Henry III of Castille, Spain. He was there because Timur had recently returned to Spain a number of Christian women liberated from Bayazit’s harem at the fall of Ankara. Henry saw this as a good occasion to thank Timur and to cement good relations with a power that Europe hoped might prove an ally against the dreaded Turks. In addition, the 15th century was a time of broadening horizons in Europe and deepening curiosity about the world. Clavijo left a detailed account of his mission, including a description of the reception of the Chinese legation at Timur’s court. (See “Clavijo’s Account of Timur’s Displeasure.” page 9.)

he struggle for the Timurid succession began immediately after Timur’s death and lasted several years, but by 1409, Timur’s son Shah Rukh had emerged as the undisputed heir of his father’s empire. In China, major changes were also under way: After dynastic fighting, Yung Lo, son of Hung Wu, had taken the throne as the third Ming emperor in 1403.

he struggle for the Timurid succession began immediately after Timur’s death and lasted several years, but by 1409, Timur’s son Shah Rukh had emerged as the undisputed heir of his father’s empire. In China, major changes were also under way: After dynastic fighting, Yung Lo, son of Hung Wu, had taken the throne as the third Ming emperor in 1403.

The sons were very different from their fathers. Shah Rukh was married to one of the most remarkable women of the age, Queen Jawhar Shad, with whom he shared wide cultural interests. He largely eschewed military exploits. Herat had long been his personal capital, and under his rule it became a city of great beauty, a center of the arts and learning famed for its cosmopolitanism. Shah Rukh was curious about foreign lands, and he encouraged ambassadors and foreign missions. Clavijo records that he was invited to visit Shah Rukh while en route to see Timur in Samarkand, but could not make the detour to Herat for fear of displeasing Timur.

|

BRITISH LIBRARY

Fourth among Hung Wu’s 26 sons, the third Ming emperor is known as Yung Lo or “eternal joy”; his given name was Chu Ti. His 22-year reign was the pinnacle of Ming power. Below: Likewise a fourth son, the infant Shah Rukh is presented to his father, Timur, in this painting from the 17th-century Zafarnama by Sharaf al-Din Yazdi. |

BRITISH LIBRARY |

Yung Lo was the son of a man who had been born a peasant but had risen to overthrow the Yuan Dynasty that had ruled China for a century. A military man, Hung Wu had also been concerned with the restoration of traditional Chinese Confucian values, including the neo-Confucian view that the emperor of China was ordained by heaven to rule the entire world, Chinese and non-Chinese alike. He fostered agriculture, and China’s standard of living rose dramatically; he legislated against merchants, whom he perceived as parasites and exploiters. Under his rule, foreign traders could only enter China with special permits—essentially in the company of diplomatic missions.

Yung Lo had spent his youth on China’s northwest frontier engaged in forestalling any repetition of the Mongol invasions from the direction of the Gobi desert. After his father’s death, he fought his nephew for the throne and won. Yung Lo was interested in extending China’s power both militarily and diplomatically: He tried to capture Annan—approximately coterminous with modern Vietnam—which led to years of guerrilla warfare; he was also the only Chinese emperor ever acknowledged as overlord by Japan. Yet like Shah Rukh, Yung Lo also passionately wanted to know more about foreign countries, and it was under his rule that the famous voyages of Zheng He were sent out to research and trade beyond the maritime boundaries of China. His was a bold approach to the outside world.

In both countries, the succession struggles were costly, especially for Shah Rukh. The turmoil depleted the energy and resources needed to resume the hostilities that had loomed in 1405. While Timur or Hung Wu might have fought anyway, regardless of the further, possibly disastrous, costs, the fact that their sons found a path away from war marks them as men of distinctly different character and temperament from their fathers. Signs of rapprochement began early: In 1407, Shah Rukh’s rival Khalil Sultan returned the surviving members of the Chinese missions of 1395 and 1397, who had had to remain in Samarkand, dispatching them together with escorts and gifts. These gifts were, inevitably, perceived by Yung Lo as tribute, but nonetheless his reciprocal gesture was much appreciated: He sent back envoys with instructions—among other things—to offer sacrifices at Timur’s tomb.

After Shah Rukh came to the throne, the flow of embassies continued, most setting out from Samarkand (and a few from Herat) along the Silk Roads. Most would stop and pray for a good journey at the Mosque of the Travelers, today known as the Mosque of Khidr, built on the site of an ancient fire-temple overlooking the Iron Gates of Samarkand.

The Chinese remained particularly keen on western horses and falcons and other birds of prey, as well as leopards and other exotic beasts, jade, sal ammoniac and various native products. The return gifts were almost invariably different kinds of silk, robes, silver and paper money, and occasionally porcelain. It suited the Chinese to have these exchanges, as they enabled China to obtain foreign luxuries while maintaining the myth of Chinese self-sufficiency. Central Asia was more frankly interested in commerce. It seemed that the relationship was stabilizing and would continue to do so as long as each side remained free to misinterpret the other in its own way.

But in 1411, trouble arose again. Yung Lo, acting on out-of-date information, ordered Shah Rukh and Khalil Sultan to stop fighting. But Khalil Sultan was already dead, and Yung Lo’s letter, like that of his father 16 years earlier, took an offensively arrogant tone: Yung Lo styled himself “Lord of all the Realms of the Face of the Earth” and addressed Shah Rukh as his vassal. Shah Rukh, for all his cosmopolitanism, was furious, and is said to have sent a rejoinder to the effect that the sooner the emperor of China converted to Islam the better it would be for all concerned.

|

|

Clavijo, too, evidently misunderstood the nature of Timur’s relations with China, for Timur never for one instant considered himself a vassal of the Chinese emperor.

Those lords now conducting us began by placing us in a seat below that of one who it appeared was the ambassador of Chays Khán, the emperor of Cathay. Now this ambassador had lately come to Timur to demand of him the tribute said to be due to his master, and which Timur year by year had formerly paid. His Highness at this moment noticed that we, the Spanish ambassadors, were being given a seat below that of this envoy from the Chinese Emperor, whereupon he sent word ordering that we should be put above, and that other envoy below. Then no sooner had we been thus seated than one of those lords came forward, as from Timur, and addressing that envoy from Cathay publicly proclaimed that his Highness had sent him to inform this Chinaman that the ambassadors of the King of Spain, the good friend of Timur and his son, must indeed take place above him who was the envoy of a robber and a bad man, the enemy of Timur, and that he his envoy must sit below us: and if only God were willing, he Timur would before long see to and dispose matters so that never again would any Chinaman dare come with such an embassy as this man had brought. Thus it came about that later at all times during the feasts and festivities to which his Highness invited us, he always gave command that we should have the upper place. Further on the present occasion, no sooner had his Highness thus disposed as to how we were to be seated than he ordered our dragoman to interpret and explain to us the injunction given in our behalf. This Emperor of China…[rules] an immense realm, and of old Timur had been forced to pay him tribute: though now as we learnt he is no longer willing, and will pay nothing to that Emperor.

—Clavijo: Embassy to Tamerlane, translated by Guy LaStrange (London, 1928) pp. 222–3.

|

|

|

|

On Islam

Aperson who understands the interpretation of the classics of the Muslim religion is called a man-la [mulla] and is revered by the common people. In the mosque the man-la sits on the right side of the common people. Even the ruler of the state honours him. When they pray, only the man-la chants. …In the capital there is a big earthen building called a mo-te-erh-sai [madrasah]. The verandas are broad on all four sides of the building. In the small courtyard, there is a copper vessel similar to a cooking pot several chang in circumference [possibly containing water for ritual ablutions]. Writing is engraved on its top and it is similar in form to a ting tripod. In every direction the rooms are beautiful, and many contain roaming students and people who truly understand the classics. They are similar to China’s great schools.

—Rossabi pp. 51–53

On Horses On Horses

Many people produce fine horses and love to shelter them carefully. All the horses are kept in earthen buildings underground where they are fed and nourished. Wind and sun does not, in this way, bother them; in winter, they are warm and in summer they are cool.

—Rossabi p. 55

On Windmills

The water mills are similar to those in China. They also have windmills which are fashioned after the walls of buildings. On the top of the walls are four sides with open doors, and outside the doors are screens which welcome the wind. On the wood all around are blades to take advantage of the wind. At the bottom of the wood, there is a millstone. When the wood blows from any direction, the poles revolve and move. From any direction, these poles catch the wind.

—Rossabi p. 55

|

There is no record in China of the receipt of Shah Rukh’s letter, however, and scholars have suggested that the envoys and translators may have—wisely—suppressed it, or modified it upon delivery, in effect giving it a different “spin.” If the letter had been delivered as written, it is unlikely that Yung Lo would have ordered a major mission to set out for Central Asia in 1413, led by Ch’en Cheng, a Chinese civil servant with wide experience of foreigners. By great good fortune, two documents of Cheng’s relating to his journey survive: one a rather uninformative diary, which breaks off suddenly; the other a fascinating account of his experiences. Central Asian envoys accompanied this mission back to China with, among other gifts, a white horse for the emperor.

|

ALEXANDER STONE LUNDE

Near the Timurid eastern gate of Samarkand stands the Mosque of Khidr, also known as the Mosque of the Travelers, where it was customary for Muslims to pray for safety on their journeys. |

In 1417, another Chinese embassy arrived at Shah Rukh’s court with lavish presents and a letter from Yung Lo. In it he wrote that “[f]rom both sides they [the Ming emperor and the Timurid sultan] should lift the veil of difference and disunity and order the opening of the door of agreement and unity, so that subjects and merchants may come and go at will and the roads may be secure.”

This was an extraordinary perception of the realities of the situation and showed an unprecedented willingness by Yung Lo to modify his approach. At a more personal level, he sent to Shah Rukh a portrait of the white horse, indicating it was a gift that had been unusually appreciated. The Chinese ambassadors were lavishly received and entertained— in striking contrast to the experiences of Chinese envoys described by Clavijo little more than a decade earlier. Again, Central Asian delegates accompanied the mission’s return to China.

In 1419 and 1420, large-scale missions again set out in both directions. The delegation from Central Asia was of particular significance in that not only Shah Rukh but also five other princes and local rulers sent representatives. As in the case of the 1413 embassy from China, we are extremely fortunate in having an account of the journey, which has been preserved by the historians of the period:

|

PAUL LUNDE The decoration of the ceiling of the Rukhobad Mosque, built about 1380, shows strong Chinese influence. |

“In the year 822 [1419] his…Majesty Mirza Shah Rukh appointed a group, at the head of which was Shadi Khwaja, on a mission to Cathay. Along with them Prince Mirza Baysunqur sent Sultan Ahmad and Khwaja Ghiyathuddin Naqqash, who was an artist of no mean talent. He established with the Khwaja that, from the day they returned, they would record on the pages of their notebooks, without addition or deletion, all they witnessed—events, condition of roads, construction of towns, description of garrisons, situations of buildings, condition of kings, and so on. When the emissaries returned, Khwaja Ghiyathuddin, in compliance with the order, presented written down in the form of a journal all he had seen, the choicest marvelous tales and rare stories of which will be quoted from his report, for the verity of which he is responsible.”

Unfortunately, none of Ghiyathuddin’s sketchbooks, which must surely have accompanied the written text, are known to have survived.

What is so remarkable about Ghiyathuddin and Ch’en Cheng’s narratives, and indeed also that of Clavijo, is the wide-ranging intellectual curiosity they exhibit and their generally tolerant attitudes. Although we know that two of the writers were, respectively, a devout Muslim and a devout Catholic, and that Ch’en Cheng, as a Chinese civil servant, must have been deeply imbued with Confucian ethics, in their accounts, interest overcomes prejudice. Obviously, there were things of which they must have disapproved: Clavijo, a teetotaler, did not much enjoy the partying at the Timurid court; Ghiyathuddin was disturbed by the implications of the kowtow. But on the whole, they were much more concerned with observing and comparing than with criticizing.

|

A Conversation With Yung Lo

The emperor asked, “In your country, is grain expensive or cheap? Is welfare for the privileged few or widespread?”

“Grain is beyond the boundaries of perfection,” [the emissaries] replied. “And welfare is more inexpensive and more widespread than can be imagined.”

“Yes,” he said, “when the ruler’s heart is with the Lord, the Creator bestows bountiful welfare.” Then he said, “I have in mind to send an emissary to Qara Yusuf [ruler from Iraq to Anatolia] and request from him some good-tempered horses, for I have heard that in his realm there are excellent horses.” Then he asked, “Are the roads safe?”

The emissaries answered, “Within the realm under Shah Rukh Sultan’s command, people come and go with utter peace of mind.”

“So I understand,” he said. “Now, you have come a long way. Arise and have some food.”

—Thackston p. 289

Yung Lo’s Secretaries

On either side of the emperor’s dais were seated two girls with faces like the moon and countenances like the sun, hair of ambergris knotted on top of their heads, their faces and necks exposed, and lustrous pearls in their ears. They held paper and pens in their hands and waited to write down what the emperor said in order to report when he went into the private quarters. If a correction or change was to be made, they sent the writing out to the clerks to implement the order.

—Thackston p. 288 |

|

|

The Chinese official histories recorded important letters—but did they record them accurately? There are elements in this letter of 1394 that suggest it is based on a genuine document, but neither the extreme humility nor the statement that the emperor, a non-Muslim, was bringing enlightenment to the world sound like anything Timur could conceivably have said or ordered written. Did Chinese clerks do a little rewriting? Or—less likely—was it Timur’s own Persian scribes who discreetly rewrote the text before it was sent out? In either case, it is possible that the humble tone of this letter evoked the arrogant tone of Hung Wu’s 1395 letter to Timur—the letter that so enraged him that it nearly precipitated a war.

I respectfully address Your Majesty, great Ming Emperor, upon whom Heaven has conferred the power to rule over all countries. The glory of your charity and your virtues has spread over the whole world. The people prosper by your grace and the kingdoms lift up their eyes to you gratefully. All they know is that Heaven wishes to regulate the ruling of the people, and ordered Your Majesty to arise and accept the fate of the throne and be Lord over the myriads…. The nations which never had submitted now acknowledge your supremacy, and even the most remote kingdoms, involved in darkness, have now become enlightened…. Whereby have we merited such favor? …I see with deference that the heart of Your Majesty resembles the vase which reflects what is going on in the world [a reference to the Vase of Jamshed, an image much used by the Persian poets]…. I can only return Your Majesty’s kindly disposed feelings by praying for your happiness and long life. May they last eternally like heaven and earth.

—From the Ming Shi (Ming Chronicle), adapted from the translation quoted in E. Bretschneider, Medieval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources, Vol. II

(London, 1888) pp. 258–260. |

Their accounts are widely different in style: Ch’en Cheng is extremely informative, but rather dry and impersonal; Ghiyathuddin describes with an artist’s eye the buildings and spectacles, and his pleasure at the lavish receptions and a wealth of visual details is obvious.

Of course, the emissaries were, in some sense, spies, or at least “intelligence operatives,” and their diaries were intended to provide information and guidelines for subsequent missions, which may explain the detailed descriptions of architecture and entertainments, as well as data of use to merchants, details on the communications and postal systems, and the workings of the bureaucracy and law, in addition to general geographical and sociological information.

There is very little evidence of direct military reconnaissance, except in Clavijo, who was caught up in Timurid dynastic wars on his way home and who found military matters laid out before his eyes. Yet it is difficult to believe that such information would be absent from the reports of such embassies. Perhaps the ambassadors were closely guarded and unable to learn much, or, more probably, the classified information was reported only orally or in top-secret “burn after reading” reports that have not survived to this day.

|

ALEXANDER STONE LUNDE

Timur and his descendants, including Shah Rukh, are buried in the Shahr-i-Zindah complex in Samarkand. Below: The Hall of Supreme Harmony in Beijing’s Forbidden City was built by Yung Lo in 1406.

|

CLAUDIA URIBE TOURI / ESTOCK PHOTO / ALAMY |

Envoys continued to be exchanged until the death of Yung Lo in 1424. His successor once again withdrew China from contact with the outside world: The voyages of exploration—notably those of Zheng He—were, like the embassies, felt to be extravagant and dangerous, potential sources of cultural, political and religious pollution by non-Chinese. This was a strict Confucian view, and the swiftness of China’s withdrawal highlights the degree to which the voyages and contacts of Yung Lo’s reign were due to the emperor’s personal interest and intellectual curiosity. Shah Rukh lived considerably longer, until 1447. After his death, things changed in Central Asia, too. Timur’s empire fragmented, Uzbek invasions altered the cultural frames of reference, shifting trade patterns decreased Silk Roads trade and, increasingly, the area became a geopolitical and cultural backwater. Shah Rukh’s intellectually curious, tolerant heirs looked southward and built another empire: that of Mughal India.

The events of these years marked an evolution in international relations. No doubt the changes were born of expediency. Shah Rukh’s refusal to subscribe to the Chinese worldview forced the Chinese to approach him by a new path, as the shift in tone of the letters from China between 1410 and 1418 shows. And he, too, moved on a long way, in terms of openness and political sophistication, from the brutal methods of his father. Like Yung Lo, through effort and repeated contact, Shah Rukh had clearly come to realize that he was dealing with a complex culture, one that was as deep-rooted as his own and which could not be altered simply by threats. Both rulers learned how to adapt to another’s point of view.

Each could have chosen war. Either could have cut off all relations, for neither empire needed the other in any vital way. But instead, Shah Rukh and Yung Lo both chose the long, slow path of compromise and diplomacy, thus earning peace and prosperity for their people and, for themselves, a historic reputation as rare rulers who were both wise and virtuous.

|

|

In the late 14th and early 15th centuries, there were some 30 recorded diplomatic missions between China and Central Asia; two-thirds of them took place in the first quarter of the 14th century.

| C.1330–1340 |

Timur born. |

| 1395 |

Embassy from China brings letter to Timur. |

| 1397 |

Another mission from China to Central Asia. |

| 1398 |

Timur sacks Delhi. |

| 1402 |

Timur captures Ottoman Ankara and sends embassy with freed Christian women to Henry III of Castile. |

| 1403 |

Yung Lo comes to the throne in China. |

| 1403–1406 |

Timur’s envoy returns to Samarkand, and Henry III sends Clavijo with him. |

| 1405 |

Timur dies at Otrar. |

| 1405–1408 |

Timur’s heirs struggle for supreme power. |

| 1407 |

Khalil Sultan, one of Timur’s heirs, returns members of 1395 mission. |

| 1408/1409 |

Shah Rukh emerges as heir to Timur’s empire. |

| 1411 |

Yung Lo orders Shah Rukh to stop fighting members of his family; diplomatic relations are again jeopardized. |

| 1413/1414 |

Major mission from Yung Lo headed by Ch’en Cheng. |

| 1417/1418 |

Another large Chinese mission to Central Asia. |

| 1419/1420 |

Large mission from Central Asia to China accompanied by writer and court painter Ghiyathuddin Naqqash. |

| 1424 |

Yung Lo dies. |

| 1426–1435 |

Hsüan Re closes China to the outside world. |

| 1447 |

Shah Rukh dies. |

|

VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

|

Caroline Stone (stonelunde@hotmail.com) divides her time between Cambridge and Seville. She is currently working with Paul Lunde on a book about the journeys of Ibn Fadlan and other Arab travelers to the north, scheduled to appear in 2007. |