|

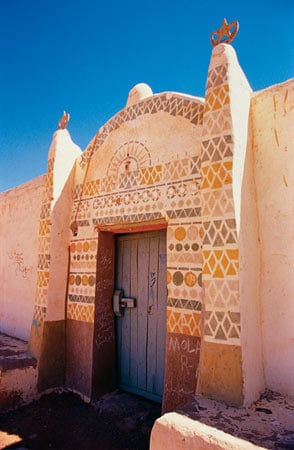

| Ornamentation typically focuses on the home’s exterior doorway, which may open on an interior courtyard or lead directly into a reception room. |

Written by Louis Werner

Photographed by Michael Nelson

he region of Upper Nubia in Sudan, lying between the Nile’s Second Cataract near the Egyptian border and the river’s distinctive S-bend some 350 kilometers (200 mi) to the south, is a land where the clock ticks to non-Arab time. Within Upper Nubia, north of the Third Cataract near Kerma, where the Mahas district begins and the asphalt and electricity end, Nubian villagers maintain their linguistic and cultural differences with great pride. To be Mahasi means to be a true Nubian, to speak a pure Nubian language and to live in the Nubian heartland.

he region of Upper Nubia in Sudan, lying between the Nile’s Second Cataract near the Egyptian border and the river’s distinctive S-bend some 350 kilometers (200 mi) to the south, is a land where the clock ticks to non-Arab time. Within Upper Nubia, north of the Third Cataract near Kerma, where the Mahas district begins and the asphalt and electricity end, Nubian villagers maintain their linguistic and cultural differences with great pride. To be Mahasi means to be a true Nubian, to speak a pure Nubian language and to live in the Nubian heartland.

But Mahas was recently spared a project whose benefits would surely have despoiled it, a project aimed dead center at the village of Kajbar at the Third Cataract and the Nubian fields and homesteads upstream. The government had planned a hydroelectric dam at Kajbar that would have flooded out tens of thousands of families and covered countless archeological sites in and around Kerma, the ancient Kushite capital. This, all agree, would have been a tragic reprise of the losses in Lower Nubia, on the Egyptian side of the border, with the building of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960’s.

Luckily, the Kajbar dam never got past the blueprint stage. An international campaign publicized the threat and successfully petitioned the Sudanese government to reconsider. A dam now under construction at an alternative site, at the Fourth Cataract of the Nile near Karima, will displace fewer non-Nubian farmers and will not disturb the archeological sites at Napata and Jebel Barkal.

If the Kajbar dam had been built, perhaps its saddest casualty would have been not a site but a type: the Nubian house, a mud-walled, stand-alone family compound centered on a courtyard and surrounded by an extensive layout of men’s and women’s quarters. The Sudanese novelist Tayyib Salih has compared such a house, often built on heights above the flood plain, to “a ship that has cast anchor in mid-ocean.”

|

|

|

| Above: Dried crocodile heads, one dried and one painted fish and geometric plaster-carving decorate the doorway and wall of a home in the village of West Sahel, near Abu Simbel in Egypt. In the courtyard of another home, top left, the wings of a dried pelican echo the arches behind it. Top right: The village of West Sahel hugs the bank of the Nile. Many of its residents, ethnic Nubians, were displaced during the building of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960’s. |

Even more distinctive than the floor plan of a Nubian house is the decoration of its exterior doorway, or bawaba, which mixes vivid color, adobe brick filigree, figurative and geometric images in mud and white lime-plaster relief, and wall-mounted objects like ceramic plates, automobile headlights, mirrors, cow horns and dried crocodiles. While the full range of these decorative materials has shrunk in recent years, the impulse to draw attention to one’s home, and to its doorway as a symbol of the family, remains strong.

Farther north, this homegrown architecture did not survive the displacement of the Egyptian Nubians. Relocated into concrete, common-walled shells in a new-lands development at Kom Ombo, north of Aswan, this change in architectural space, more than anything else that happened to them in their move, has been a main reason for their gradual “arabization” over the last 40 years. Something similar has happened to a smaller number of Sudanese Nubians relocated from Wadi Halfa, at the southern reaches of Lake Nasser, to Khashem al-Girba east of Khartoum on the Atbara River.

Because of the clear demarcation of cultivable and uncultivable land along the Nubian Nile, houses there can be built right at the edge of the green fields, taking advantage of the view and the cooling humidity. Unlike, say, in the Nile Delta or in a new agriculture development off-river, a Nubian house could be amply proportioned and comfortably situated because it did not occupy otherwise productive land.

Abdallah Salih Suleiman, age 75, lives in such a house near Kerma. He was born on Badeen Island in mid-channel and remembers his old home’s outer wall adorned with a white lime-plaster image of a lion holding a sword, surrounded by sunbursts. “Whenever a child in the family lost a tooth, he would throw it at the wall, and where it struck, in that place we would then paint a sunburst as a wish for a new tooth. Our doorway also had a plaster cattle egret, which we call here sadeeq al-mazreeq, or friend of the fields, because it is always a welcome guest.” Egrets eat insect pests and make the farmer’s job that much easier.

|

| Painted motifs, plaster carving and—in the blind arch above the door—a crocodile head decorate this home. |

As do many people his age, Abdallah regrets that times seem to change for the worse. “Before, we put a lot of effort into our house designs and into things around the house, like pottery and floor mats. But now we think we can buy beauty, so we stop making it—but we are wrong. There is nothing better than something homemade.”

A Nubian proverb has it that “one man cannot build a house, but 10 men can easily build 20 houses.” This sense of the collectivity of household architecture, both for those who build and those who dwell within, remains valid today. Extended families live under one roof, and houses are expanded when newly married couples take up residence and require their own private room.

|

| Nubian houses today increasingly resemble Arab ones in the use of separate men’s and women’s rooms built off a central shaded courtyard. Both painted and three-dimensional objects, here fans and baskets woven of palm fronds, are part of the decoration. |

The late art historian Marian Wenzel was a member of a multidisciplinary team that documented Nubian life and culture in the mid-1960’s, before it was submerged by Lake Nasser. Her book House Decoration in Nubia (1972, University of Toronto Press), which applied the methods of art criticism to social anthropology, established the chronology of design motifs and techniques in Upper Nubia during the 20th century. Starting with the supposition that no artwork is anonymous and no folk tradition is truly timeless, she determined that the iconography of Nubian house décor was a 20th-century phenomenon, traceable to the handiwork of a few known builders-turned-artists.

A primary demand for decorated walls was created because of a new building material suddenly available—the iron railroad rail—which increased the practical dimensions of interior rooms, and thus the length of otherwise plain exterior walls. The rails were salvaged from a British railroad extended from Wadi Halfa to Kerma as part of Kitchener’s campaign to reconquer Sudan. It was abandoned in 1905 when construction began on the direct line from Halfa to Khartoum via Abu Hamid.

|

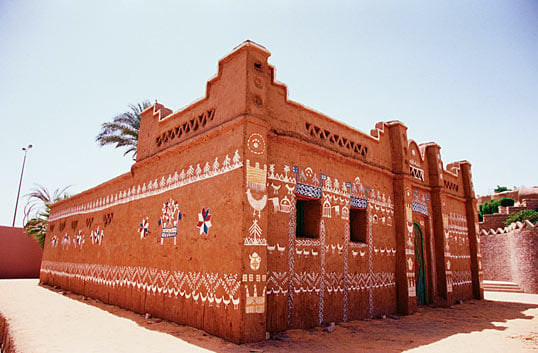

| While many motifs recur frequently, the differences in decoration from one house to another are often lively. The home at right has an all-geometric decoration. Much of the Nubian style is attributed to a builder-artist of the early 20th century named Ahmad Batoul, whose iconography has become “traditional.” |

Wenzel found that what once had been an anonymous profession of masons and plasterers became, through the work of a house builder named Ahmad Batoul, an artistic specialization. Batoul, who was born in Lower Nubia before moving to Sudan in the 1920’s, established the accepted images and treatments for decorating exterior walls, and his style became so recognizable that, decades later, Wenzel could spot his handiwork throughout the Halfa and Mahas districts.

At the same time, the intrusion of the import market economy, in the form of product advertising and logos brought home by Nubian laborers returning from domestic-service jobs in Egypt, provided Batoul with his imagery. The sword-carrying lion that is such a common sight on Nubian houses represents Ali, son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad. The image arrived in the form of tin cutouts tacked onto wedding chests imported from Egypt and stuffed with the consumer goods of Cairo and Alexandria.

Huntley & Palmers brand tea-biscuit tins, imported into Sudan from the famous Reading firm from the 1880’s onward, were decorated with images of flowers and Art Deco geometrics; those later ended up as standard design motifs on the walls of houses. The tins were ubiquitous throughout the country by the turn of the 20th century. After the 1898 Battle of Omdurman, an abandoned Mahdist sword scabbard was found that had been repaired with strips cut from such a tin.

By far the most distinctive materials, however, were ceramic plates and saucers. Adhered to the wall, they were believed to guard the house against the evil eye, superceding the earlier reliance on shiny pebbles and shells. Nubians returning from hotel work in Egypt brought with them these icons of the western, individually served meal. (Many Nubians still eat their food communally, and in earlier days served it on woven reed disks, which are still used as tray covers.)

|

|

Muhammad al-Shazali, president of Khartoum’s Nubian Club, is particularly proud of the club’s own doorway, a freshly painted assemblage of semiabstract zoomorphic images—crocodiles, hippos and egrets—in two-tone stucco. “For guests,” he says, “it is a sign that they have come to Nubia. For Nubians, it is a sign they have come home.” Like similar clubs in Aswan, Cairo and Alexandria, the Khartoum club caters to nostalgic Nubians, living far from their home villages, who yearn to gather regularly among compatriots.

Kerma is the site of ancient Deffufa, a settlement dating from Nubia’s First Intermediate Period (2500–2050 bc), which had trade relationships with Egypt from the Middle Kingdom onwards. The site has been excavated over the last 25 years by a Swiss team led by Charles Bonnet. Deffufa consists of a 50-foot-high mud-brick citadel, a landmark for miles around, surrounded by cemeteries and residential quarters.

The German Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius visited Deffufa in 1842 and called it “an extensive city spread wide over the plain in which two large monuments were conspicuous. They are not pyramids but oblong squares quite massive and strong and built of good firm unburnt Nile bricks.” His book Discoveries in Egypt, Ethiopia, and the Sinai… (1852) contained a good color lithograph of the citadel.

Bonnet’s excavation of a modest dwelling in the residential quarter shows architectural parallels to contemporary Nubian houses, with their buttressed and pilastered doorways and courtyards—and probably also with their geometric wall decorations, which Bonnet postulates because of similar designs he found on Deffufan pottery.

The decorative use of ceramics and white lime-plaster decreased as colored paints became available on the market. In the rocky parts of northern Mahas, yellow and red stone-based pigments had made possible a broader palette, but the introduction of brighter artificial pigments in the first decades of the 20th century quickly pushed out the monochromatic look. As wooden doors gave way to sheet metal, oil-based paints could be applied to their best reflective, smooth-coated effect. Today, the art of polychrome doors with tinted stucco on their flanking pilasters has reached its own pinnacle of inventiveness.

Yet Nubians are nostalgic for their lost wooden doors. Salih Ibrahim Ahmad, a Halfawi now living in Khartoum, remembers the Nubian exodus from his homeland when neighbors could salvage only their doors and their personal effects. In Khartoum’s Ethnographic Museum, the only Nubian artifacts on display are two old doors (kobid, in Mahasi Nubian) with their wooden locks (dogul) and keys (kushar)—symbols, says Salih, of male and female fertility.

Osman Muhammad Orsud, a 50-year-old Mahasi living in the hamlet of Buyud (“Eggs”) near Argo, offers a tour of the old gateways near his house. “Most face south,” he notes, “in order to stay clear of the north wind. That also helped them to survive as long as they have. Otherwise, the wind would have erased them completely.” Osman’s house may be freshly plastered and painted, but every day he takes time to admire the old details.

|

| The “chicken-and-shrub” design becomes a frieze that defines the bottom of a band of decoration that goes all around this house; the top is marked by a repeated “tree-and-grass” pattern. Color marks the door and windows on the front. |

The same architectural finishes on 20th-century walls and gateways—blind arches over doors, openwork in the shape of tented bricks as a running wall cornice, and square cross reliefs—were also found north in Faras and south in Old Dongola in houses dating from Nubia’s Christian period (sixth to 14th centuries). Some historians say that many elements of Nubian folklore, such as immersing newborns in the river, crossing their foreheads with kohl, and rattling a copper mortar and pestle in their ears, also date from this period.

The Nubian crowns found painted on Christian-era tomb frescoes at Faras West, merging upturned cow horns with a crescent held aloft on a stem, were adapted in the 20th century as a purely decorative motif on household walls, both in whitewash and as actual horns set over doorways. Such imagery predates even the medieval era. Under New Kingdom pharaohs and then under the Ptolemies, Nubians were permitted to take statues of the cow goddess Hathor and moon goddess Isis from the Philae temple to their own sanctuaries south of Abu Simbel each year in a pilgrimage.

In the river town of Kerma al-Nuzl (“the Alighting”), named for the former train terminal built here, two traders nearing 70 years of age remember the days gone by. Kamil Hamid Harun, a Mahasi, and Abd al-Latif Abaa Yazeed, a Kenzi Nubian from Aswan who came here as a boy, reminisce about how they had to learn Arabic because Kenzi and Mahasi dialects are so different, how the first automobiles that came to town had headlights brighter than the moon, and how the Nile flood of 1946 changed their childhood. “The waters stayed high for 20 days,” says Kamil, “and then came the disease and the dying—malaria.”

Many houses were destroyed then, especially the grandest ones because they were closest to the water, they recall. Abd al-Latif mentions how a boat carrying the umda’s (town leader’s) mother away from her flooded home capsized; she drowned, but 30 other passengers swam to safety. Kamil’s father rebuilt his house on Simit Island but did not stay. “Our fields were full of sand.” Kamil did go back to the house four years ago, just to see. “It was partly collapsed,” he said. “But it was still beautiful, and big, just as I remember it.”

“A maze of a house,” as the author Tayyib Salih remembered it from his own childhood, “cool in summer, warm in winter…. Somehow, as if by a miracle, it has surmounted time.”

|

Louis Werner (wernerworks@msn.com) is a free-lance writer and filmmaker who lives in New York. |

|

Michael Nelson (masrmike@gmail.com) is the Middle East regional photo manager for the European Pressphoto Agency (EPA) in Cairo.

|