|

| ROBERT GRUTZ |

| Juanita is a pure Spanish Barb living outside Tucson, Arizona. Her ancestors were the Barb horses that crossed into Spain from North Africa in the eighth century with the Arab–Berber invasion, and from there traveled with the Spanish conquistadors to the New World. |

Written by Jane Waldron Grutz

In the year 715, the first Muslim governor took office in southern Spain, a land of verdant valleys, rich pastures and seemingly unlimited possibilities—the land the Arabs called al-Andalus.

After the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632, the message of Islam had swept out of Arabia, eastward as far as the Punjab and west into North Africa. The old Byzantine provincial capital at Carthage fell to the Muslims in 698, and a dozen years later, a combined Muslim army of Arabs and Berbers entered the Iberian Peninsula.

|

| AMERICAN NUMISMATIC SOCIETY |

| A Carthaginian gold coin, struck in about 260 BC, depicts a Barb of the Numidian cavalry, which fought both for and against Carthage in its long struggle with Rome. |

There were many reasons for the Muslim successes in what is now Spain and Portugal. The Visigoth rulers were divided over their own succession, as apt to fight on one side as the other. The disenchanted slaves, serfs and freemen of Iberia easily succumbed to a force more motivated than their own. But there was a military reason as well: The Visigoth knights, weighed down by heavy armor, were no match for the highly mobile Arab and Berber cavalry, which was mounted on exceptionally swift, agile horses known as “Berbers” or, more commonly, “Barbs.”

|

| FROM ARTE DA CAVALLARIA DE GINETA E ESTRADIOTA, ANTONIO GALVANI D’ANDRADE (1677) |

| When the Muslims rode into Spain in the year 711, they did so on Barbs fitted with short stirrups and neck bits, a riding style later called jineta that gave the rider great maneuverability. Spanish riders adopted the style and carried it to the New World. |

The Barb was an important component of the Arab–Berber armies that entered Spain. During the early years of Islamic expansion, Arab forces had moved on foot and fought as infantry accompanied by small contingents of camel cavalry, for the Arabian horse was too highly valued to use as a cavalry mount. The Barb, the native horse of North Africa, was a breed especially well suited to the so-called “jineta” style of riding, in which the rider relied on his horse to place him in position to throw, thrust, parry or dodge as required. Named after the Zanatah tribe of what is today Algeria, this style required a steed trained to anticipate the rider’s actions and obey without hesitation. Seldom taller than 14 hands, Barbs were nimble and responsive to the slightest touch of the reins. They were accustomed to harsh environments, strong, surefooted, fleet yet smooth. Their strong loins and quick intelligence enabled them to master and perform the quick turns and elevated positions required in close combat. Most of all, the Barb had extreme courage, and was unfazed by blows and wounds. To the contrary, Barbs often seemed to relish a fight.

|

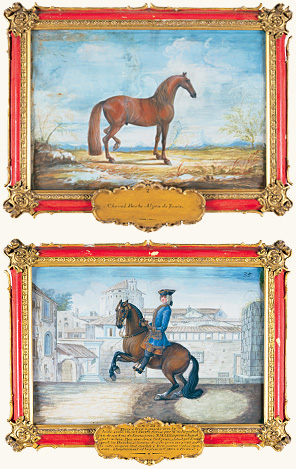

| COLLECTION OF THE EARL OF PEMBROKE, WILTON HOUSE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY (2) |

| Two watercolor portraits of horses at the Spanish Riding School show “Alzan de Tunis” and an unnamed horse performing a levade in St. Mark’s Square, Florence. “Without doubt, the Spanish Horse is the best horse in the world for equitation,” wrote Baron Reis d’Eisenberg, a prolific painter of horses and author in 1759 of l’Art de monter à cheval (The Art of Horsemanship). |

o one can say exactly where or when the Barb originated. Like most horses of the ancient world, the Barb was the result of years of crossbreeding by peoples who migrated from one land to another. By Roman times, however, the Barb seems to have taken its basic form, already very similar to that of its Iberian cousin, separated as they were only by the Strait of Gibraltar.

o one can say exactly where or when the Barb originated. Like most horses of the ancient world, the Barb was the result of years of crossbreeding by peoples who migrated from one land to another. By Roman times, however, the Barb seems to have taken its basic form, already very similar to that of its Iberian cousin, separated as they were only by the Strait of Gibraltar.

“They are small and not very beautiful,” commented the second-century writer Claudius Aelianus of the Barb, then known as the Numidian horse. But to their credit, he added, they were “extraordinarily fast and strong and withal so tame that they can be ridden without a bit or reins and can be guided simply by a cane.”

It appears the Romans first came in contact with Barbs as the mounts of the Numidian cavalry during the Second Punic War. (The Numidians were a Berber tribe occupying an area now in Algeria.) The Romans noticed their qualities and, after Rome destroyed Carthage at the end of the Third Punic War (149–146 bc), Numidian horses became an important part of the Roman cavalry.

Many of the Roman Numidians, however, came not directly from North Africa, but from the Iberian Peninsula, which the Carthaginians had invaded in 238 bc to establish a base from which to launch the Second Punic War. The Carthaginians brought large numbers of Barbs into Iberia, and it seems likely that they were later cross-bred with native Spanish horses at the many Roman stud farms whose remains archeologists have found throughout southern Spain and Portugal.

Under Muslim rule in al-Andalus, an important new fusion of Barb and Spanish blood took place. The result was the Andalusian, which nearly 300 years of Umayyad patronage refined in the grasslands around Córdoba to become one of the most beautiful horses of all time.

As the years went by, the Andalusian was periodically refreshed with new Barb blood, especially after 930 when Ceuta and other North African cities entered the Umayyad orbit. “Horses of the highest quality” were transported to Cordoba, wrote scholar Maribel Fierro. By the end of the 10th century, al-Mansur, regent and de facto ruler of al-Andalus, had become famous throughout the Muslim world for his stud and his special strain of Barb warhorses. The later Almoravid and Almohad Dynasties (1090–1145 and 1145–1212 respectively) were both Berber in origin, and it must be assumed that the northbound traffic in Barb horses continued during the years of their rule.

|

| FROM NIHAYAT AL-SUL (A MANUAL OF HORSEMANSHIP AND MILITARY PRACTICE) / BRITISH LIBRARY / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| A 1371 Mamluk cavalry manual shows training exercises using Barb mounts. |

As a result, there can be little doubt that the Muslim rulers of al-Andalus rode the finest horses of their time. Unfortunately, no prints or paintings of any of these rulers are known to exist. Today, we can imagine the medieval Andalusian horses only by looking at their successors, as painted for the Spanish royal family by Diego Velázquez.

The stallion ridden by Philip III shows clear Barb characteristics: the luxuriant mane and tail, the proud arched neck, even the so-called “Roman” nose. But there are differences too: The horse pictured by Velázquez is broader in the chest and hips than the typical Barb and, as R. Cunninghame Graham points out in Horses of the Conquest, there is “not too much space between its belly and the ground.”

As was often the case in 16th-century equestrian portraits, the horse of Philip III is shown performing the levade, a dressage movement greatly admired at that time, which demands exquisite balance, strong loins and a willingness to perform. Although these qualities are present in the Barb, they may be present to an even greater degree in the Andalusian.

Baron d’Eisenberg, author in 1759 of l’Art de monter à cheval, wrote that “without doubt, the Spanish Horse is the best horse in the world for equitation, not only because of his shape, which is very beautiful, but also because of his disposition, vigorous and docile, such that everything he is taught with intelligence and patience he understands and executes perfectly.”

|

|

| DIEGO RODRIGUEZ DE SILVA VELÁZQUEZ / MUSEO DEL PRADO / ERICH LESSING / SCALA / ART RESOURCE (2) |

| Interbreeding Barb and Spanish horses, the Umayyad court at Córdoba developed the Andalusian, which later became the

preferred mount of much European royalty, including Isabella of Bourbon and Philip III of Spain, whose Andalusian stallion is posed executing the levade. |

In the late 15th century, there was a strong influx of Andalusian blood back into North Africa as Muslims, forced to leave Spain by the Christian reconquest, took their beloved horses with them. Around the same time, Italy fell into the grip of “palio fever.” Often conducted around or through the city piazza, palios were races held on feast days. So often did imported Barbs win these races that in time the word barberi came to mean simply “race-horse.” Many of the Italian nobility began to acquire Barbs: Cosimo de’ Medici of Florence, Federico da Montefeltro of Urbino, the Duke of Ferrara and, not least, the Gonzaga family of Mantua.

The Gonzagas’ stables had long been among the best in Europe. Records from 1488 indicate that Francesco Gonzaga (1466–1519) owned some 650 horses, and the privileged position of his Barbs is evidenced by the Codice dei Palii Gonzagheschi, an illuminated manuscript that showed off his beloved barberi to peers and clients. His son Federigo (1500–1540) went further: He had portraits of his four top barberi painted nearly life-size on the walls of the grand reception room of his beautiful new Palazzo Té in Mantua, where they remain to this day.

|

| GIULIO ROMANO / ERICH LESSING / ART RESOURCE |

| In the 16th century, Gonzaga Barbs imported from Algeria won many palio races in Italy. Today, four portraits of top racers adorn the walls of the reception room in the Palazzo Té in Mantua. |

The Gonzagas entertained there some of the most influential figures of the day, including, twice, the Hapsburg Emperor Charles v. Although Henry VIII of England never journeyed to Italy, he knew about the barberi: When Henry explained he wished to begin a stud in his own country, Federigo dispatched a gift of seven Barb mares and a magnificent Mantuan Barb stallion, said to be literally worth his weight in silver. In response, Henry graciously replied that the horses were “not only beautiful but of surpassing excellence,” adding that he had never ridden a horse that pleased him more. Indeed, so taken was Henry with the Gonzaga Barbs that he went on to obtain as many fine additional Barbs as he could, along with a few Andalusians.

The English Royal Stables continued to grow under Elizabeth i, who appointed the Earl of Leicester to the coveted position of Master of the Horse. Leicester soon obtained even more Barbs, though Elizabeth I discouraged the purchase of Andalusians, as she was not then on friendly terms with Spain.

The Gonzaga mystique affected Charles I as well. Less interested in horses than art, he acquired the fabled Gonzaga collection of paintings for a vast sum that he might better have used to support his ill-equipped armies—an example of the profligacy that in 1649 would cost the king his head.

It was not long until England also lost its royal stud. The cost of maintaining it was prohibitive, and in 1651 Oliver Cromwell ordered the king’s horses sold to the highest bidders. Unfortunate as this may have seemed to royalists, it contributed to the quality of England’s northern horses generally. As Sylvia Loch points out in The Royal Horse of Europe, the descendents of Henry VIII ’s “imported coursers were to constitute the foundation lines for the Royal Mares, destined to be served by oriental stallions a century and a half later, making England the home of the finest racing horse in history.” She refers, of course, to the English Thoroughbred, descended from three 18th-century foundation stallions: the Darley Arabian, the Byerley Turk and the Godolphin Barb, sometimes called the Godolphin Arabian. Although the Godolphin never raced, many great champions were numbered among his offspring.

But speed and stamina, critical as they are for a race- horse, are not the Barb’s only qualities. It is also known for its strong, short- coupled body, perfect for “collection”— the posture that makes weight-bearing easiest for the horse—its eagerness to learn and its gentle nature. These qualities came into play in dressage, the art of horse-and-rider performance.

|

| EUGÈNE FROMENTIN / MUSÉE D’ORSAY / ERICH LESSING / ART RESOURCE |

| The Falconer, which Eugène Fromentin painted in Algeria

in 1863, is one of his numerous works from that period that include Barb horses. |

In the 1530’s Federico Grisone established the first great school of dressage in Italy. This was followed in 1594 by that of Antoine de Pluvinel in Paris, whose most famous pupil was Louis XIII, performing with his Barb stallion Bonnitte. The English royalist William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle, established his own school while in exile in Holland, and his best-known royal pupil was Charles II. Cavendish wrote of Barbs: “I freely confess they are my favourites…. The best stallion is a well chosen Barb, or a beautiful Spanish horse.”

For the most part, however, Andalusians and Barbs continued to serve widely as popular riding and warhorses. And so it was that these were the horses that Isabella of Castille directed Columbus and his followers to take aboard when they set out to seek gold in the New World.

Beginning with the second voyage of Columbus in 1493, horses in their hundreds were shipped out in the flimsy cockleshell boats of the time, a journey of two to three months. The losses were severe. If the ship were becalmed too long in the appropriately named Horse Latitudes, the horses were thrown overboard for lack of water.

But for all the horses that were lost, many survived. Of these, most thrived in the rich grazing lands of the West Indies. In 1609, Inca Garcilaso de la Vega wrote in his General History of Peru that “the first horses were taken to the islands of Cuba and Santa Domingo and then to the other Windward Islands, as these were discovered and conquered. Here they bred in great abundance and were taken thence for the conquest of Mexico and Peru.”

Horrific as the deeds of the conquistadors seem to modern sensibilities, it should be remembered that, outnumbered by thousands, they most certainly would have faced defeat if it were not for their horses, which presented a terrifying and novel sight to the Native Americans. This fact was not lost on the conquistador Pedro de Castaneda de Nagera, who stated that “horses are the most necessary things in the new country because they frighten the enemy most.” Indeed, in report after report back to Charles v appears the phrase, no doubt deeply felt at the time, “After God, the victory belongs to the horses.”

|

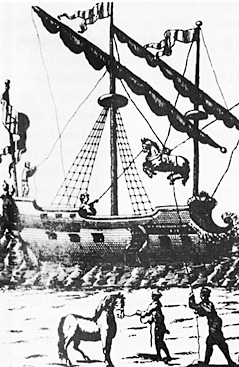

| FROM MANEJO REAL EN QUE SE PROPONE LO QUE DEBEN SAVER LOS CAVALLEROS, MANUEL ÁLVAREZ OSSORIO Y VEGA, 1769 |

| The first horses in the Americas arrived having survived the three-month voyage suspended in canvas slings. Near shore, they were hoisted outboard by gun tackle. |

By the end of the 16th century, the Spanish had fanned out north and south in the Americas, establishing not only missions, but also stud farms. Native Americans often served as grooms at these farms. Although at first the Spanish forbade natives to ride, in time horses came into native hands—a few as gifts, some by theft, and others after escaping into the wild. Great herds soon spread, and by the 18th century some Native American tribes owned these horses by the thousands.

The very best were reserved as buffalo-hunting horses and warhorses. In the early days, most of these “wars” were in fact raids on rivals, and the Native Americans—particularly in what became the central us—liked their horses to be in paint and feathers. The horse that to many looked best in this regalia proved to be a bright pinto or a colorful Appaloosa or “Medicine Hat” horse. (See “The Medicine Hat Barb”)

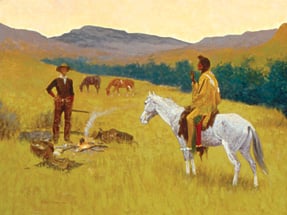

In the 19th century, these horses were immortalized and romanticized in paintings by Charles Russell and Frederick Remington. Their work closely mirrored that of such earlier French artists as Eugène Delacroix and Eugène Fromentin, who traveled to North Africa following the arrival of French rule in Algeria in 1830. In both the American West and North Africa, the painters often showed these Barbs and their western descendents in action or even in combat.

|

| FREDERIC REMINGTON / FUNDACIÓN COLECCIÓN THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA / ART RESOURCE |

| Barb and Spanish horses were prized by North Americans of

the Plains and Southwest, and their horses could often outrun those of the European settlers—including US cavalry mounts. |

In Algeria, the French military established the spahi, or local cavalry, mounted exclusively on Barb stallions. The most famous unit, the Seventh Spahi, fought bravely for France in both World Wars. After Algeria won her independence in 1962, many departing spahi officers brought their Barbs back to France. One was a veterinary surgeon named Jean Deveaux, who in 1978 established l’Association Française du Cheval Barbe, which has grown to more than 2000 members, so popular has the breed and its variations become in France. More recently, similar associations have been organized in Belgium, Germany and Switzerland, and all are allied with the Algiers-based Organization Mondiale du Cheval Barbe. (See “The French Barb”)

Likewise, there are Barb associations in the United States—but it took tragedy to bring them about. As European settlers moved westward and clashed with Native Americans, the Europeans noticed that the native horses were often superior in combat. In reprisal, the US cavalry not only destroyed many Native American horses, but also deliberately crossbred them— particularly the Appaloosas—with larger, less nimble, horses.

Likewise, there are Barb associations in the United States—but it took tragedy to bring them about. As European settlers moved westward and clashed with Native Americans, the Europeans noticed that the native horses were often superior in combat. In reprisal, the US cavalry not only destroyed many Native American horses, but also deliberately crossbred them— particularly the Appaloosas—with larger, less nimble, horses.

The situation was worse for the wild horses, the mustangs whose herds were the gene pool from which the Native Americans drew their steeds. It is widely believed that at one time more than two million mustangs roamed North America. Settlers, however, often regarded them as grazing competition for cattle.

|

| GEORGE CATLIN / SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM / ART RESOURCE |

| A portrait of Sauk and Fox chief Keokuk from 1835 shows him mounted on a Spanish horse in a pose that recalls European royal mounted portraiture. |

And so began a great slaughter, second in bloodiness only to that which befell the buffalo. Beginning early in the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of mustangs were systematically killed, and many were sold for pet food. Today, an estimated 50,000 mustangs survive; roughly half roam government lands, protected, since 1971, by the Bureau of Land Management.

Since the 1950’s, private associations such as the Spanish Mustang Registry, the Spanish Barb Breeders Association and the Horse of the Americas Registry have drawn attention to the heritage and endangered status of the Spanish mustang. The US organizations share the goals of their North African and European counterparts: the preservation of a breed that, for more than 2000 years, has served in war and competition and—perhaps most important—has proved a comrade and companion to generations across continents.

In his 18th-century writing on dressage, Baron d’Eisenberg lauded the Barb as “one of the most beautiful amongst all horses in the world.” He went on to note that because the Barb is docile and has a good memory, he is “easy to train, as long as it is done with kindness and discretion, and with delicate aids; but never with harshness, or long lessons, which wear out his good will, or stifle his disposition, which is in fact the best among all horses in the world.”

Courageous, intelligent, companionable: It is easy to see why the Barb would elicit the effusive sentiment posted by one French breeder on his Web site: “The Barb is more than a horse,” he wrote, “It is a friend for life.”

|

The Rancher Barb

|

| ROBERT GRUTZ |

In North America today, descendents of the Spanish horses are known variously as Spanish Barbs, Spanish Mustangs or Colonial Spanish Horses. The differences, explains Silke Schneider, who works to preserve rare breeds on her Desert Heritage ranch outside Tucson, lie less in the horses themselves and more in the goals of the horse registries that employ the terms.

“By selecting the horses that best typify the Spanish Barb type, the Spanish Barb Breeders Association is trying to bring the horse back to the way it was when it arrived in the 16th century,” Schneider says. “The Spanish Mustang Registry is trying to preserve and perpetuate the last remnants of the true Spanish Mustang. The Horse of the Americas is trying to bring all these horses under one umbrella.” Hence the term “Colonial Spanish Horse,” which she says was coined as a generic term for all American horses of Spanish descent. Perhaps more significant are the strains within these types: Any horse may come from a feral strain, a rancher strain or a tribal strain. (Ranchers and tribal horses must be shown to be descended from confined, unadulterated herds.)

Schneider’s two Spanish Barbs, Juanita and Pilar Wilbur, are ranchers whose forebears lived for more than 120 years on the Wilber-Cruce ranch in Arivaca, Arizona. When they came to her in 1989, they had never been ridden. “They had never even seen anyone riding a horse,” she says. Yet just nine weeks later, Schneider—who does not consider herself a trainer—was able to ride Juanita in the Tucson Rodeo parade.

Schneider believes that Barbs often learn simply by watching and imitating.

“Normally, you have to teach a horse to align himself with a gate so you can open it,” she says. But after a few minutes watching other horses perform the task, Pilar Wilbur took her cue and sidled up close to the gate so Schneider could easily unlatch it.

She is also quick to note that successful owners of Barbs do not “break” wild horses; rather, because it is the spirit and companionable nature of the animal that so enchants them, they treat those qualities with respect.

The horses respond in kind. When Schneider visits Spanish Barbs running free on a nearby ranch, they rush over, anxious to greet her, to be petted and perhaps to enjoy a treat.

“They love people,” she says, pointing out what may be the most engaging quality of any Spanish Barb. “They just love people.”

Contact: www.horseweb.com/desertheritagebreeds |

|

The Medicine Hat Barb

|

| ROBERT GRUTZ |

To Native American warriors, the markings of a “Medicine Hat” pony were auspicious: a warbonnet on its head, a shield across its chest, a shield of brown to protect its rump and shields on its sides to protect its flanks.

Alan Bell’s 11-year-old mare Mariah is such a horse. Taller than most Barbs, she looks as if she has just stepped out of a painting by Remington or Russell.

“She’s a granddaughter of San Domingo,” says Bell, referring to the famous Medicine Hat stallion that belonged to Robert Brislawn, who in 1957 founded the Spanish Mustang Registry, the first of its kind in the us. San Domingo was named after the Navajo pueblo in New Mexico whose residents brought the stallion in from the wild.

Though San Domingo had many offspring, authentic Medicine Hat markings are rare, and he never sired a Medicine Hat colt, though he did sire several fillies. One of these fillies, Pepita, came to live in Iowa, where Bell, who raises horses near Dallas, found her and brought her home to his El Rancho Wakan. Some time later Pepita gave birth to her Medicine Hat look-alike, Mariah.

Bell soon discovered his little Pepita had the courage of a lion. When another horse entered Bell’s compound, he was amazed to see Pepita herd the other mares into a corner and sally out. The fray was brief, and it was the intruder who ran off with a bite in his backside.

Courage is one Barb attribute. Intuition is another. “You can take a Spanish Barb down a trail, and a couple of miles before the end, he’ll start to fidget and want to turn around. It will turn out that the trail ahead is washed out. I don’t know how he knows it,” says Bell, “but he knows it.

“The Barb is not a push-button horse,” he adds.

Some people find such independence in a horse annoying, but for breeders like Bell, it’s all part of the charm of their beloved Spanish Barbs.

Contact: www.bellsspanishbarbs.com |

|

The French Barb

|

| ROBERT GRUTZ |

The hilly green country north of Valence is a land of horses. At one farm, racers train on a makeshift track; further along, Percherons graze in tall grass. At Les Balmes there are Barbs—more than 80 of them, all belonging to Philippe Jacquelin, organizer of trail rides, trainer of Barb circus horses and since 2000 president of l’Association Française du Cheval Barbe.

Originally planning a teaching career, Jacquelin made the national rugby team and later played for the team in Romans, a town near Les Balmes. He fell in love with the area and decided to establish an equestrian academy to offer long rides through the countryside. Though at first he used many breeds of horses, he soon discovered that the one his customers preferred was the easily controlled, smooth-gaited Barb.

He tells one story of a 72-year-old woman who came to him to buy a horse. Sensing she wanted an animal of quality, he brought out a beautiful, spirited three-year-old Barb stallion. After one look, she stated flatly, “I cannot ride this horse.”

Jacquelin replied, “You must try.”

She did, and some time later she returned and declared, “I will buy this horse.”

“Seventy-two years old,” Jacqueline repeats. “She did not ask the price. She did not ask his pedigree. She simply said, ‘I will buy this horse.’”

Jacquelin shrugs, pleased but hardly surprised that the woman would take such a fancy to his well-mannered Barb.

Most of Jacqueline’s Barbs were raised at Les Balmes, but he has a special place in his heart for the Algerian national stud at Tiaret, birthplace of Lahdjar des Balmes, his champion Barb stallion, five-time champion of France and 2005 European champion, listed in both the French and Algerian studbooks. One look at Lahdjar’s refined head, luxuriant mane and tail and fluid movements, and you are left with no doubt as to why he has won the judges’ favor.

By any standards, Lahdjar is a horse of impeccable manners and great beauty. And, as usual, Jacquelin knows exactly why this is so. “Lahdjar is Barb,” he explains. “Pure Barb.”

Contact: http://elevagedesbalmes.com |

|

Jane Waldron Grutz, a former staff writer for Saudi Aramco, is now based in Houston and London, but spends much of her time working on archeological digs in the Middle East. Recently her interest in history has broadened to include North Africa, Spain and the Americas, and the Barb horses that link those regions. |