Written by Andrea Shalal-Esa

Photographed by David H. Wells / Aurora Photos

|

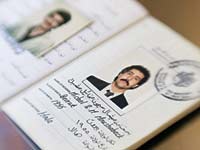

| Founder and publisher Michel Moushabeck came to New York from Lebanon in 1981, and founded Interlink six years later. |

ushly illustrated travel and history books, novels translated from Arabic, lavish cookbooks, a swirl of non-fiction works and even a book of political cartoons by an American Muslim all crowd the small table at the American–Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee convention. The venue is a swanky Washington, D.C. hotel, but with vendors wedged in narrow hallways, selling literary wares amid the chatter of old friends

ushly illustrated travel and history books, novels translated from Arabic, lavish cookbooks, a swirl of non-fiction works and even a book of political cartoons by an American Muslim all crowd the small table at the American–Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee convention. The venue is a swanky Washington, D.C. hotel, but with vendors wedged in narrow hallways, selling literary wares amid the chatter of old friends  and new acquaintances, there is a decidedly Middle-Eastern, suq-like atmosphere to the place.

and new acquaintances, there is a decidedly Middle-Eastern, suq-like atmosphere to the place.

Interlink publisher and founder Michel Moushabeck, dressed all in black, has lugged in enough books to fill much more than his single table, and he is replenishing, stacking and rearranging to show off as many titles as possible. He pauses to answer questions, chat with writers and make recommendations to the undecided. One Iraqi–American customer eagerly snaps up the last five copies of Iraq: An Illustrated History, a 240-page color guide that Booklist called “an absolutely riveting excursion” that leaves the reader “enlightened and awestruck.”

Over the past 20 years, Moushabeck and his staff—which now numbers 10—have built Interlink Publishing into one of the fastest-growing independent publishers in the US. From its converted warehouse in Northampton, Massachusetts, Interlink releases about 50 titles each year, including many award-winners, and it counts more than 500 titles on its backlist. Two new fiction titles out this fall are Everything Good Will Come by Sefi Atta of Nigeria, which won the Wole Soyinka Prize for African Literature, and The Image, the Icon, and the Covenant by Palestinian writer Sahar Khalife, which won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature.

“Like music and art, literature is the doorway to a country’s soul. It speaks to the heart, tells you what history books hide, what mindless media do not reveal, what mainstream tourist guidebooks cannot possibly capture,” says Moushabeck, whose parents fled Palestine for Lebanon in 1948. “It will give you insight into the way of life, the customs and traditions of the society, but it will also fill baffling silences and take you on a journey into the minds and hearts of the people.”

Interlink’s World Fiction series, which was launched in 1988, just a year after the press’s founding, now comprises 85 titles and includes authors from all over the Middle East: Syria, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Libya, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Palestine and Iran.

Interlink’s cookbooks—64 of them now—also span the globe, each a feast for the eye, beautifully written and illustrated to whet the reader’s appetite. These titles, Moushabeck explains, often sell better than fiction, and thus their revenues help support Interlink’s fiction list. This fall, Sur la Table, one of the largest kitchenware chains in the US, plans to feature two Interlink titles—Modern Caribbean Cuisine and Moroccan Modern—in its stores and catalog and on its Web site, providing a visibility that most independent presses only dream of. In 2006, three of The Los Angeles Times’s 10 “cookbooks of the year” were Interlink titles: Cucina Romana, India with Passion and Moroccan Modern.

Interlink’s cookbooks—64 of them now—also span the globe, each a feast for the eye, beautifully written and illustrated to whet the reader’s appetite. These titles, Moushabeck explains, often sell better than fiction, and thus their revenues help support Interlink’s fiction list. This fall, Sur la Table, one of the largest kitchenware chains in the US, plans to feature two Interlink titles—Modern Caribbean Cuisine and Moroccan Modern—in its stores and catalog and on its Web site, providing a visibility that most independent presses only dream of. In 2006, three of The Los Angeles Times’s 10 “cookbooks of the year” were Interlink titles: Cucina Romana, India with Passion and Moroccan Modern.

In non-fiction, several titles—including A Taste of Lebanon, Interlink’s very first cookbook—have sold more than 100,000 copies. This is a rare feat in the US non-fiction market, where only a handful of the 175,000 books published each year sell more than 5000 copies and the average book sells an extremely modest 99!

aving completed his bachelor’s degree in international business at New York University in 1981, Moushabeck founded Interlink six years later. Coming to America from war-torn Beirut, he says he embraced freedom, democracy, education and free speech, but he was shocked at how little people knew about his homeland.

aving completed his bachelor’s degree in international business at New York University in 1981, Moushabeck founded Interlink six years later. Coming to America from war-torn Beirut, he says he embraced freedom, democracy, education and free speech, but he was shocked at how little people knew about his homeland.

The new press started small. Some early titles, such as The Quranic Art of Calligraphy and Illumination by Martin Lings, showcased the cultural heritage of the Arab world; others critiqued US policy in the Middle East and other world hot spots. He and his first wife, Ruth Lane Moushabeck—today vicepresident of Interlink—rented a basement in Brooklyn’s Arab neighborhood on Atlantic Avenue, and there they stored the first shipment of books—much to the chagrin of the delivery driver.

“I still remember the face of the 18-wheeler truck driver when he showed up at the sidewalk of the address he was given,” Moushabeck remembers. “He looked mortified.” With no loading dock and no forklift, Moushabeck unloaded the 20 pallets of books himself, one carton at a time.

They had no experience as publishers, but they had a vision. “We knew we wanted to publish books that had an international perspective, books that enhanced people’s understanding of the Middle East, books that we believed in—books that inspired us,” he says.

But the Moushabecks, by then with two young children, were soon nearly penniless as the debts started mounting. They realized they needed to differentiate their books from those already on the market.

“I recall thinking to myself, ‘If you genuinely want to learn about another culture, you must read its history written from the perspective of the people of that country; you must travel there independently and not on a pre-packaged tour; you must share their food and learn how to cook it; and you must—and this is an absolute must—read the literature of leading novelists in the country,’” he says.

Moushabeck spent a week scouring the shelves at one New York bookstore after another to see what was already available on the US book market—and what was missing. He soon hit on the idea of developing specialized travel guides for history buffs, art lovers, bird watchers, divers, wine enthusiasts and other niche readers. For cookbooks, he decided to focus on world cooking, “the type of cookbooks that double as cultural guides— those that you can read in bed as well as in the kitchen.”

In fiction, “the door was wide open,” he says, noting there was very little translated fiction from the Middle East, Africa, Latin America or the Caribbean available in the US at that time. Moushabeck became determined to publish the best of the world’s contemporary fiction and introduce North American readers to the many writers who had achieved wide acclaim in their home countries, but who remained largely unknown beyond those borders.

he formula has worked remarkably well, aided in large part by the timely advent of Amazon.com and other Internet-based sales outlets, which offset the advantages that bigger publishers have in chain bookstores. More recently, in a post-9/11 world hungry for information about Arabs and Muslims, Interlink has become the publisher of Middle Eastern literature. This summer it sold the millionth copy in its travelers’ history series, and its books have become standard texts at universities around the country.

he formula has worked remarkably well, aided in large part by the timely advent of Amazon.com and other Internet-based sales outlets, which offset the advantages that bigger publishers have in chain bookstores. More recently, in a post-9/11 world hungry for information about Arabs and Muslims, Interlink has become the publisher of Middle Eastern literature. This summer it sold the millionth copy in its travelers’ history series, and its books have become standard texts at universities around the country.

|

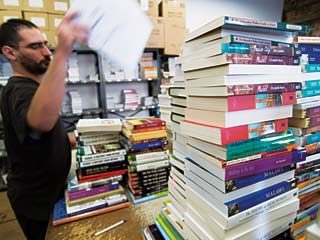

| Derin Stevens prepares an order in Interlink’s shipping department. The press publishes some 50 new titles a year, maintains 500 on its backlist and has become the leading publisher of literature translated from Arabic into English. |

“What Interlink has done is revolutionary. There’s nothing else quite like it,” says Steven Salaita, a professor at Virginia Tech who also serves as executive director of the Radius of Arab–American Writers, Inc. (RAWI), a professional organization for writers and scholars. “Nobody has brought so many voices to an American readership,” he says, adding that he often uses Interlink books to help his students see the heterogeneity of the Arab world and the influence of Arab women.

To introduce its books to new audiences and place them “in the hands of educators, teachers—people who make a difference,” Moushabeck says, Interlink attends nearly 40 trade, academic and international conferences each year.

Palestinian–American poet and playwright Nathalie Handal, who tried for years to interest larger publishers in an anthology of poetry by Arab women writers, lauds Moushabeck’s courage. When Interlink published her book The Poetry of Arab Women: A Contemporary Anthology in 2001, it promptly collected several awards, including the pen Oakland– Josephine Miles 12th Annual National Literary Award, and it became an Academy of American Poets bestseller. It has sold more than 10,000 copies—a phenomenal achievement for any book of poetry.

Retired professor of mass communications Jack Shaheen, who has published extensively on media images of Arabs, says he feels comfortable working with Interlink because he trusts Moushabeck and Interlink’s editors not to fiddle with his basic message.

|

| Since 1994, Interlink’s headquarters in Northampton, Massachusetts have been in this renovated 19th-century factory. |

Shaheen’s Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People came out in July 2001 and has since become a key reference in film studies. Late this year, Interlink will publish Shaheen’s analysis of post-9/11 film and television trends that continue to cast Arabs in stereotypical roles.

“Interlink is to be applauded for revealing Arab humanity, in all different kinds of publications, and shattering stereotypes, especially of women,” says Shaheen. “It fills a gap.”

Moushabeck says he enjoys working with authors and launching the careers of bright young writers, but he considers his job “literary midwifery—helping bring great literary works out into the world.”

Interlink has grown into a “cultural and literary bridge” between western readers and the Middle East, he says, noting that books translated from Arabic often present viewpoints rarely heard in western media, and that Interlink books by westerners, when translated into Arabic by Middle Eastern publishers, also offer readers there new insights into western culture and political thinking.

“Our books are valuable because they enhance and broaden people’s understanding of other cultures,” Moushabeck says. “They contribute to a debate on important social and political issues both in the West and in the Arab world.”

|

Andrea Shalal-Esa is a correspondent for Reuters in Washington, D.C. Her essay on Arab–American writers was published in Etching Our Own Image: Voices From Within the Arab American Art Movement (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007) and her entry on Arab–American literature will appear next year in Greenwood’s Encyclopedia of American Literature. |

|

David H. Wells (www.davidhwells.com) is a free-lance documentary photographer affiliated with Aurora Photos (www.auroraphotos.com). He specializes in intercultural communications and the use of light and shadow to enhance visual narratives. |