|

|

| |

At Mazayin al-Ibl, spectators admire a prize-winning herd. |

Written by Peter Harrigan and photographed by Lars Bjurström

riving across the empty, flat, sandy plain of Um al-Rughaiba, about 320 kilometers (200 mi) north of Riyadh, with 160 more sandy kilometers (100 mi) to go to the town of Hafr al-Batin, there is little to reveal that, for a few weeks each year, this featureless area hosts one of Saudi Arabia’s largest festivals.

riving across the empty, flat, sandy plain of Um al-Rughaiba, about 320 kilometers (200 mi) north of Riyadh, with 160 more sandy kilometers (100 mi) to go to the town of Hafr al-Batin, there is little to reveal that, for a few weeks each year, this featureless area hosts one of Saudi Arabia’s largest festivals.

Several recently laid asphalt roads intersect the straight, two-lane highway, and they look as though they might lead off to settlements over the eastern horizon. But no: After a few kilometers, they end in the sand. They mark the perimeter of the temporary city that springs up here each November, a city of tents and trucks and livestock that covers about 100 square kilometers (39 sq mi)—an area more than one and a half times the size of Manhattan Island. There is nothing to hint that one of these side roads will become a main street, or that another will lead past a row of impromptu buildings and tents to an arena that sprawls over the equivalent of two US football fields.

It begins in the months after high summer, when drovers of more than 100 camel herds, comprising roughly 10,000 camels, begin journeys that last days or weeks and culminate here before the practiced eyes of camel judges. In one sense, it’s a migration built on tradition: Since long before modern nations drew borders in the Arabian Peninsula’s deserts, in years with good early rains, the Um al-Rughaiba region has been a fall grazing magnet for herds from throughout the northern, central and eastern provinces of Saudi Arabia as well as from Kuwait and as far off as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. But these days, the November gathering occurs regardless of the rains, and it is taking on a new international significance.

In Arabic, this is Mazayin al-Ibl, “The Best of the Herds,” a vast camel show that attracts more than 160,000 people, from unschooled Bedouin herders to the private-jet set. All come to show, admire—and sometimes buy—the finest specimens of Camelus dromedarius, and to celebrate a resurgent Arabian heritage now in modern trappings. At its height,

on the eve of the weekend when the winners are announced and paraded in the main arena, and the owners collect prizes worth some $2 million, the views and sounds from the fringes of the vast encampment are mesmerizing.

|

| Set up to accommodate more than 160,000 participants and spectators—and some 10,000 camels—the tent city at Um al-Rughaiba covers an area half again as large as New York’s Manhattan Island. |

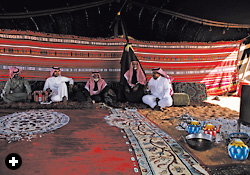

As dusk falls over the desert and the day’s final call to prayer, al-‘isha, rolls across the plain, hundreds of small

generators begin whirrs and chatters that will last till dawn. In the light of the lamps and campfires that brighten the tents, trailers and canopies, patches of glowing orange

reflect from the copper sides of coffee pots, and the rough bell tones of mortars grinding coffee ring out amid random bellows, roars, growls and grunts from camels. Pickup

trucks bounce and rattle across the sand, their red tail-

lights bobbing and their headlights sweeping, picking out white canvas marquees and long, low-slung, traditional

tents made of camel-hair cloth.

As night draws in, the movement quiets, dust settles and a sky of stars stretches down to the horizon. Songs, laughter and chatter rise with the smoke of campfires. Fireworks arc into the sky from soirées that go into the wee hours.

As night draws in, the movement quiets, dust settles and a sky of stars stretches down to the horizon. Songs, laughter and chatter rise with the smoke of campfires. Fireworks arc into the sky from soirées that go into the wee hours.

Despite 21st-century mechanical intrusions, the scene evokes the often greater pre-industrial gatherings of tribal confederations in the northern Arabian Peninsula. In 1912, Carl Raswan, a young German traveler and Arabian-horse breeder, after journeying through empty desert for weeks, wrote in awe of such an encampment: “Scattered across the desert rose seven thousand tents and thousands of camels; tens of thousands were cropping the miniature plants. Never could I have imagined such as sight as these congregations of camels spreading out towards the rising land.” He describes a city of tents: “Smoke rose from thousands of black dwellings, and in between large camel herds, hundreds of them, were wending their way home.” Such gatherings often numbered more than 100,000 nomads, with even greater numbers of livestock, but, unlike Mazayin al-Ibl, they often took place over the parched summer months,

when the tribes gathered their herds around wells.

Today, Mazayin al-Ibl is the signature event in

a series of roughly a dozen smaller provincial shows, loosely referred to in English as “camel beauty pageants” or even “Miss Camel competitions.” But such flippancy does scant justice to

the events. These are Arabian camel shows, where camel connoisseurship is refined and handed down over generations. Unlike at horse, cattle or other stock shows in the West, the camels here are considered not only for individual qualities of breeding, form, character, coat, grooming, color, posture, gait and so on, but also for their qualities in a herd as a whole.

|

| Adorned with tassels and embroidered strapping,

a herd of black camels

marches toward the arena. According to breeding standards, the ears of a fine black camel will be distinctly upright. |

From his wood-paneled library in a quiet Riyadh suburb, linguistic anthropologist and ethnographer Saad Abdullah Sowayan expounds on the virtues of the dromedary with enthusiasm and eloquence. “The Arabian camel is the strongest yet most tender, patient and beautiful of animals. It’s a fantastic example of adaptation with dignity, mansuetude, nobility and high standards.”

Sowayan focuses on the significance of the camel in Arabic language, culture and literary heritage. Understanding this, he says, is a clue to understanding today’s rising interest in camel shows throughout the Arabian Peninsula. “Once you have delved into the rich corpus of poetry where camels feature, you have a reference point, and you know what to look for. There is a deep attachment and a concept of beauty. You have to study and understand the literature as well as the animal

in order to be able to fully appreciate it,” says Sowayan, who has spent several decades in the field researching, recording and writing on the cultural elements, poetry, language and symbolism associated with the Arabian camel.

|

| A poster announces the grand prize award and royal sponsorship of Mazayin al-Ibl. |

Sowayan explains that, metaphorically, the animal that was first domesticated some 4000 years ago became “the means of transmitting the oral tradition,” for Bedouin poems typically opened with phrases like “I send this poem to you on so-and-so camel,” and in the poem’s prelude, the poet demonstrated his literary artistry and encyclopedic knowledge with an elaborately lyrical, expert description of a fine mount. After the recitation, the hearer would memorize it, and his own camel would then carry him, and the poem, to another community.

“Camels are an inexhaustible source of Bedouin lore. Conversation always leads back to them,” Sowayan says. Culturally, he argues that the camel is “more important to us than the Arabian horse. A good part of the imagery, metaphor, motifs, and much of the esthetic and linguistic repertoire of Arabian oral literature relates to the camel. Since it can do just about everything a horse can do and then more, the camel still deserves a lot more credit than it is getting.”

Regional and especially international media coverage of Mazayin al-Ibl and other camel shows reinforces Sowayan’s point, as reporting often ignores this tradition and focuses instead on the exotic and the quirky, reinforcing a condescending, comic stereotype of the camel as a symbol of cultural backwardness. Articles that acknowledge the complexity, nuances and underlying historic significance of the event are rarely seen in western coverage.

It doesn’t help, however, that, though the name “Mazayin al-Ibl” has the right ring to it in Arabic, “The Best of the Herds” so far defies an English translation that conveys

the appropriate gravitas. English-language signs around the awards arena can be even less helpful: One declares, “Increasing interest in Arabian Camels as a result of the King Abdulaziz Prize of Fancy Camels.” For an event comparable to the Arabian Breeders World Cup horse show in Las Vegas, the Crufts Dog Show in the UK, or the National Western Stock Show in Denver (the self-proclaimed “Super Bowl of cattle shows”), it can almost seem, well, unfair.

|

| Displaying the discipline that won it "Best of the Herds," a herd of white camels stands at attention. |

As in all such competitions, picking out prize animals is serious business. Over early-morning mint tea, Arab coffee and steaming glasses of fresh camel milk served in his camel-hair tent near the main enclosure, Abdullah bin Jilawi shares his insights into camel judging. A keen camel breeder from the Al-Hasa Oasis in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, Bin Jilawi is president of the Mazayin al-Ibl’s seven judges, tasked with selecting prize animals from among males, females, several color categories, different

age groups and, finally, the best in show.

I had hoped that he would whisk us off to one of the many nearby herds and demonstrate his judging technique, but, with traditional Arab politeness, he quietly explains that this will not be possible: For the president of judges, or indeed any of the judges, to home in on

one herd, or even a single camel, outside his official rounds could immediately set off rumors among dealers and breeders, for once

a camel is announced

as a prize-winner, its value skyrockets. As an example, Bin Jilawi tells of one winning camel in 2003 that was valued at roughly half a million US dollars before the event; after winning best in show, it commanded a price seven times greater. Others seated in the tented majlis are quick to agree with Bin Jilawi, and they all have anecdotes of similar cases.

|

| Judges evaluate both individuals and herds. |

The judging actually takes several weeks, with the judges making their way among the herds scattered widely across the desert around Um al-Rughaiba. They carefully look first at the herds for their general qualities, narrowing contenders into groups of 10 and then assessing individuals within the group.

“As well as physical features, we also assess the gait of the camels, we pick out the strong in groups, and we view the way the whole herd moves, looking for a unified, orderly and naturally relaxed movement. Then we home in on individuals,” says Bin Jilawi.

He goes on to explain how judges assess characteristics differently within the main color categories. “On a camel from a black herd (mijaheem), we expect larger feet with upright ears. On the light brown gold breed (sha’al), we look for medium-sized feet and ears that are raked back and not upstanding.” Camels from a white herd (maghathir), highly valued and generally the most popular with spectators, should have ears that are low set and well raked back.

He explains how competitions were once oriented to families, clans and tribes. Now, he explains, they have become increasingly geographically based, broadly regional and more inclusive, as entrants to the Saudi contest increasingly make the trek from home ranges in Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman—four of the other five Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states. There were some two dozen GCC entrants last year. “In just a few years, we have made huge strides with this show. Foreign countries are now approaching us from outside the GCC to ask if they can enter camels. We are planning to internationalize the event beyond the region,” says Bin Jilawi.

|

| Another carefully groomed herd awaits a judge's eye. The herd's drover is mounted, in the background. |

Another change, he says, has come in recordkeeping. Until recently, owners and breeders relied on memory for every detail of the genealogies of their individual camels. Now, technology is lending a hand, as high-bred camels are increasingly registered on computer databases. Similarly, a new wireless, handheld scoring device is automating the calculation of the judges’ results, allowing judges to maintain greater anonymity.

Logistics at Mazayin al-Ibl are managed by Mohammed Abdullah Fallaj, a former football player from the Riyadh Hilal team. He speaks of the plans under way to improve the festival’s facilities: zoning to ensure that camels are separated from the main market area and clear avenues within the encampment for fire safety. “Traffic management is one of our biggest challenges. Thousands of vehicles converge on the site. We have plans to mark out and surface an expanded grid system of roads,”

he says, adding that plans also include a hard helicopter landing pad for medical emergencies, an airstrip upgrade

and improved fire, police, civil-defense, ambulance and

veterinary stations.

|

|

| Top: Top prize for the finest camel is the ’Abd al-’Aziz Award, given here by

HRH Prince Meshal ibn ‘Abd al-’Aziz, who has been the leading developer of Mazayin al-Ibl in recent years.

The award is named for the prince’s father, founder of the modern state of Saudi Arabia. Above: After the

ceremonial plaque, the second part

of the grand prize award is keys to this Hummer H2. In addition, there are more than 70 smaller vehicles awarded as prizes, from pickups

to SUV’s. |

Government support for Mazayin al-Ibl and many of

the country’s smaller camel festivals lies largely with the Supreme Commission for Tourism (SCT). To provide a field visit for the judging of camels, the SCT’s Ali al-Ambar, who holds a Ph.D. in ethnology, takes me on a tour of herds that are slowly heading toward the show area, their owners hoping for prizes.

He spots a herd of white camels moving as a train, and

we stop as they approach. Their strides are graceful, even

languid. “What a beautiful herd!” he exclaims. Al-Ambar explains that judges look at such individual traits as the frame and overall configuration; the head, neck, face, eyes, ears, mouth, lips; legs, joints and feet; coat texture; and shape of the tail. The members of this herd, he points out, are impeccably groomed: Camels are often washed, and even shampooed, in preparation for the show.

Back in the exhibit area, al-Ambar introduces Ghaeed al-Mutairi, whose family has kept prize camels for generations. Al-Mutairi has lost exact count of prizes he has won at provincial competitions, but he believes he and his 21-year-old son Ahmed have picked up at least 10 vehicles in the last 18 months. After winning first prize—a Toyota Land Cruiser

—in the dark brown (safir) category in 2006, al-Mutairi was offered more than $1 million for the camel, but he refused, preferring to keep it for breeding. Ahmed, he says, has developed an eye for winning camels, and he believes the youth has the skills to become a judge one day.

Al-Mutairi is on the lookout for new breeding stock from other herds, and once he has spotted a prospect, he sends a proxy to make an offer and negotiate. In this way, he recently bought a three-year-old camel which—after several years of care and feeding on a diet that includes whole-grain wheat bread, camel milk and dates—he expects will bring a price that will repay his outlay a hundredfold.

Al-Ambar goes on to introduce judge Jasser al-Mutairi

(no relation to Ghaeed), who appears not to share Bin Jilawi’s concerns about describing his job in situ. On a nearby specimen,

al-Mutairi uses his long cane to rapidly point out attributes of

the well-bred camel. “The coat

is important. We look for curly hair, like coiled springs. The tail should not be too long, wide at the root, tapering to its end and edged with an attractive mane. The back legs should have smooth, curved contours, nicely rounded at the joints to the fore with the two legs widely spaced apart.” And what of the all-important food

store, the iconic hump? “That’s simple,” he replies, tapping the mound of fatty tissue: It needs to be high, well-placed and upright on a long back. That takes him down to the animal’s side, which needs

to be in perfect proportion to an attractive sweeping undercarriage housing the animal’s three stomach compartments.

Bedouins developed a wide range of vocabulary to differentiate camels according to sex, color, age, size, fitness, habits, qualities, defects and other distinctive features. They also developed specific words for camels when in a group, camels loose

at pasture, camels organized in caravans, camels grouped for raiding parties and camels in other circumstances.

The 19th-century orientalist scholar Baron J. F. von Hammer-Purgstall, who served as Austrian ambassador in Constantinople, published numerous texts and translations of Arabic, Persian and Turkish authors. He also enumerated the various names for the camel in

Arabic, counting 5744 different names and epithets.

Today, poetry retains enormous

popular appeal in the Arabic-speaking world, as evidenced by shelf space given over to displays of poetry titles in bookstores and by the weekly prime-time tv show “Poet of the Millions,” beamed throughout the Arabian Peninsula from Abu Dhabi. The program, in which contestants’ skill at extemporizing

and reciting verse is judged by audience voting via text message, American Idol–

style, commands the highest rating in the Arab world, with a regular audience of 70 million. Topics and themes have included parental respect, Arab coffee

—and, of course, the camel.

|

|

| Stalls in the market area offer camel paraphernalia and accessories. |

“And,” al-Ambar adds, “there’s so much more to it. Small details are vital. He hasn’t even begun to explain what’s expected from the feet or the features and positioning of the head.”

On awards weekend, the herds congregate around the public arena, which is bounded by earthen berms some 3.5 meters (12') high. At one end, there are bleachers for the public, with seating capacity of more than 5000, and at the other end is an open-sided marquee with seating for about 500 people. Next to that is a giant tent set with dining tables for a similar number of invited guests. Handlers lead the winning animals into the arena, where they are paraded before the audience and presented with ribbons. The owners receive commemorative shields and trophy cups, and the grand prizes come from a lineup of more than 70 new, desert-ready vehicles, from Nissan pickup trucks to the grand prize, a Hummer H2.

The economics of camel dealing are no less intricate than the judging. There are critics who complain that camel prices have been inflated by speculators or, worse, wealthy dilettantes dabbling in a kind of retro fashion. But experienced owners and breeders know that a good eye is just the beginning: Constant attention, feeding and expert care are all required to develop and keep a prize camel.

The opportunity for trading creates a busy camel market with live auctions and discreet private deals. Other stalls in the market area do a brisk trade in camel consumables, camel paraphernalia and camel accessories: saddles, bridles, decorative jackets, neck bands, silver

tassels and bells; feed, salt licks and veterinary remedies

(both traditional and patented pharmaceutical); as well

as dvds, audio cassettes, books and pamphlets on poetry, Bedouin songs, camel folklore and specialist academic subjects. There are also stores that sell peripherals to modern “SUV nomads”: camping equipment, handicraft items and bulk foodstuffs, including varieties of rice, grains, dates and herbs. And for those who just want

to relax and enjoy the atmosphere, watch life go by and chew the cud, there are fast-food stalls and coffee shops serving espresso and cappuccino.

It was not camel shows, however, that began the cultural rescue of the camel from precipitous decline: Camel racing did that. Beginning in the 1950’s as oil revenues rose, nomadic populations moved to settled communities and motorized vehicles took over the camel’s once-essential role in transport. In 1964, with the support of King Faisal ibn ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, Saudi Arabia held its first major organized national camel race, which was also the first in the larger region. In the coming decades, throughout the country, camel racing over prepared courses became one of the few active reminders of the heritage associated with the animal.

In 1985, what had by then become Riyadh’s prestigious annual royal camel race spurred interest in wider heritage activities, and the first Janadriyah Heritage and Culture Festival was inaugurated north of the city. Today, this annual festival, one of the largest in the Arab world, still opens with a camel race that now attracts more than 600 contestants. Similarly, in the 1980’s and 1990’s, the sport

also took off in Qatar, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates and Oman. It has grown into a full-blown modern sporting business, now making use of microchips, computerized records, camel drug testing, research and breeding centers using artificial insemination and embryo transfer, camel hospitals, dedicated training and exercise facilities and “robot jockeys,” introduced in 2004 in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

The popularity of racing helped bring about the demise of one camel stereotype—that of the plodding beast of burden

—as it helped promote the more alluring qualities of speed, endurance and grace. This in turn heightened interest in breeding and in the definition of the camel’s archetypal characteristics in much the same way as horse racing spurs interest in horse shows.

|

| In his traditional Bedouin black camel-hair tent, partitioned by hand-woven divider walls, a Riyadh breeder serves coffee with dates, tea and fresh camel milk to a steady flow of visitors. |

Nearly 60 years ago, H. R. P. Dickson, long-time British resident representative in Kuwait, mentioned thoroughbred horses in an analogy designed to help westerners appreciate the variety among camels. After numerous journeys into the deserts of northern and eastern Saudi Arabia, he wrote in The Arab of the Desert: A Glimpse into Badawin Life in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia that “the difference between a good riding camel and the ordinary pack camel is as marked as the difference between a thoroughbred racehorse and an ordinary carthorse. Like the thoroughbred horse, [the riding camel] possesses a small head, wide forehead, small nostrils, longish ears and large eyes, and is wonderfully gentle and understanding. In body she is slightly built with thin legs, giving the appearance of fine lines. Her movements resemble those of the gazelle, whether she is at rest and grazing or moving at full speed.” And he adds, “the chief characteristic of the well-bred camel… is its staying power.”

Today, as corporate sponsors increasingly line up to support Mazayin al-Ibl and other contests alongside government backing, the event is moving into the mainstream of regional attractions.

Other Gulf states are organizing camel shows, too: In Abu Dhabi, the Authority for Culture and Heritage (ADACH) held the Mazayin Dhafra Camel Festival in April. Mohammed Khalaf al-Mazrouei, director general of ADACH and deputy head of the festival’s committee, sees the event as part of his country’s efforts to promote local folklore through cultural events. “Purebred camels have been part of Arab cultural, social and economic life, and they will remain so to future generations as young participants take part in this festival,” he says.

In Riyadh, Sowayan hopes this will be so. “Since its domestication, Arabs have developed a symbiotic relationship with the camel. Those that live in close harmony with

it can readily appreciate it both esthetically and materially,” he says. “And for all of us,” he adds, “the richness of Arab poetry continues to set and provide a perfect template for assessing the fine and beautiful qualities of a prize camel. The Arabian camel is not just surviving. It’s surviving with its head high.”

|

| A mother shades her calf, born during the festival. |

The most celebrated poems of the pre-Islamic period were known

as the mu‘allaqat (“suspended”). They earned this name because they were considered sufficiently outstanding to be hung on the walls of the Ka’bah in Makkah for public display. The typical poem of this period is the qasidah, or ode, which normally consists of 70 to 80 pairs of half-lines. Traditionally, qasidahs describe the nomadic life, and they open with a lament at an abandoned camp for a lost love. The second part praises the poet’s camel (or, in some cases, his horse) and describes a journey and the hardships it entails. The third section contains the main theme of the poem, and finishes by extolling the poet’s tribe and vilifying its enemies. The excerpt that follows is from the qasidah by Tarafah ibn al-‘Abd, who

is regarded as the greatest pre-Islamic Arab poet, if not the greatest of all time.

Ah, but when grief assails me, straightway I ride it off

mounted on my swift, lean-flanked camel, night and day racing,

sure-footed, like the planks of a litter; I urge her on

down the bright highway, that back of a striped mantle;

she vies with the noble, hot-paced she-camels, shank on shank

nimbly plying, over a path many feet have beaten.

Along the rough slopes with the milkless shes she has pastured

in Spring, cropping the rich meadows green in the gentle rains;

to the voice of the caller she returns, and stands on guard

with her bunchy tail, scared of some ruddy, tuft-haired stallion,

as though the wings of a white vulture enfolded the sides

of her tail, pierced even to the bone by a pricking awl;

anon she strikes with it behind the rear-rider, anon

lashes her dry udders, withered like an old water-skin.

Perfectly firm is the flesh of her two thighs—

they are the gates of a lofty, smooth-walled castle—

and tightly knit are her spine-bones, the ribs like bows, her

underneck stuck with the well-strung vertebrae,

fenced about by the twin dens of a wild lote-tree;

you might say bows were bent under a buttressed spine.

Widely spaced are her elbows, as if she strode carrying the two

buckets of a sturdy water-carrier;

like the bridge of the Byzantine, whose builder swore

it should be all encased in bricks to be raised up true.

Reddish the bristles under her chin, very firm her back,

broad the span of her swift legs, smooth her swinging gait;

her legs are twined like rope untwisted; her forearms

thrust slantwise up to the propped roof of her breast.

Swiftly she rolls, her cranium huge, her shoulder-blades

high-hoisted to frame her lofty, raised superstructure.

The scores of her girths chafing her breast-ribs are water-courses

furrowing a smooth rock in a rugged eminence,

now meeting, anon parting, as though they were

white gores marking distinctly a slit shirt.

Her long neck is very erect when she lifts it up

calling to mind the rudder of a Tigris-bound vessel.

Her skull is most like an anvil, the junction of its two halves

meeting together as it might be on the edge of a file.

Her cheek is smooth as Syrian parchment, her split lip

a tanned hide of Yemen, its slit not best crooked;

her eyes are a pair of mirrors, sheltering

in the caves of her brow-bones, the rock of a pool’s hollow,

ever expelling the white pus more-provoked, so they seem

like the dark-rimmed eyes of a scared wild-cow with calf.

Her ears are true, clearly detecting on the night journey

the fearful rustle of a whisper, the high-pitched cry,

sharp-tipped, her noble pedigree plain in them,

pricked like the ears of a wild-cow of Haumal lone-pasturing.

Her trepid heart pulses strongly, quick, yet firm

as a pounding-rock set in the midst of a solid boulder.

If you so wish, her head strains to the saddle’s pommel

and she swims with her forearms, fleet as a male ostrich,

or if you wish her pace is slack, or swift to your fancy,

fearing the curled whip fashioned of twisted hide.

Slit is her upper lip, her nose bored and sensitive,

delicate, when she sweeps the ground with it, faster she runs.

Such is the beast I ride, when my companion cries,

“Would I might ransom you, and be ransomed, from yonder waste!”

— From “The Ode of Tarafah” in The Seven Odes,

A. J. Arberry, translator. 1957, Allen & Unwin.

|

Peter Harrigan (harrigan@fastmail.fm) lived in Saudi Arabia for more than 20 years, where he taught English and served as an editor and reporter at several publications. He currently divides his time between Jiddah and his home in the Isle of Wight.

|

|

Lars Bjurström (larsbjurstrom@hotmail.com) is a dentist at King Faisal Specialist Hospital in Riyadh. He has a

special interest in photography of Saudi wildlife and culture, has contributed to several books on these subjects and has produced a film, “Travels in the Sand.” |