While in Egypt, I became interested in the cuisine of ancient Greece and Rome. I found that more than a few surviving recipes, such as Squash Alexandria-Style and Parthian Chicken, called for a gum resin taken from a plant called silphium. Silphium grew only in the region of eastern Libya known as Cyrenaica, and “Cyrenian silphium” was widely popular in Greece and Rome from the sixth century bc to the first century of our era, when it was believed to have become extinct. After that, Roman cooks turned to asafoetida as a substitute, a sufficiently similar spice that Persian traders brought to Rome.

|

Above: Most asafoetida on grocery shelves is a powdered compound with added gum arabic, flours and turmeric.

Below: Bulk asafoetida is bought and sold by spice wholesalers such as this one in Delhi.

|

|

TOP: SAWDIA; Above: MONEY SHARMA / DRIK INDIA /

MAJORITYWORLD |

To find some asafoetida in Cairo, I headed to the well-known Harraz Herb Shop near bustling Bab al-Khalq square. The shop resembled a medieval apothecary, with row upon row of seeds, powders and baskets of dried plants, and shelves filled with bottles of essential oils. I bought a fist-sized lump of brown-gray resin. Slightly sticky to the touch, it was as dense as a block of wood. Mostly, though, it was remarkable for its terrible, aggressive smell—a sulfurous blend of manure and overcooked cabbage, all with the nose-wrinkling pungency of a summer dumpster. The stench leached into everything nearby, too, which meant I had to double-wrap it and seal it in a plastic tub if I wanted to keep it in the kitchen.

Later, as cookbooks suggested, I unwrapped the lump, scraped off a pea-sized piece of resin and dropped it into olive oil to sauté. The transformation was astonishing: When heated, the asafoetida disintegrated in the hot oil and gave off a rich, savory scent, reminiscent of sautéed onions. It bestowed a delicate base flavoring to the dishes I made. It quickly became obvious why something that had at first seemed so repulsive proved so popular, first in the ancient world and up to the present day in a number of countries—especially India, where it is used in everything from pickled dishes, chutneys and curries to vegetarian dishes and lentils (dal). In the West, asafoetida remains virtually unused, with one exception: It’s an ingredient in Worcestershire sauce, which was based on a recipe from a British officer returned from colonial India.

|

he earliest mention of asafoetida in the historical record dates from the eighth century BC, when the plant was listed in an inventory of the gardens of Babylonian King Marduk-apla-iddina II. Not long after that, in Nineveh (near modern Mosul, Iraq), asafoetida was included in a catalogue of medicinal plants in the library of King Ashurbanipal.

he earliest mention of asafoetida in the historical record dates from the eighth century BC, when the plant was listed in an inventory of the gardens of Babylonian King Marduk-apla-iddina II. Not long after that, in Nineveh (near modern Mosul, Iraq), asafoetida was included in a catalogue of medicinal plants in the library of King Ashurbanipal.

From that beginning, the story of asafoetida reaches from ancient India and Persia to Rome, the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad, medieval Europe, India’s Mughal Empire and modern Afghanistan and Iran. Its story is also closely entwined with that of its mysterious lost cousin, silphium.

The word asafoetida is a linguistic meeting of East and West: aza means “resin” or “mastic” in Persian and foetida means “stinking” in Latin. While “stinking resin” seems adequately descriptive, other languages use colorful adaptations of the notion of “devil’s dung” for the spice: şeytan tersi in Turkish; Teufelsdreck in German; dyvelsträck in Swedish; merde du diable in French and esterco-do-diabo in Portuguese. In Afghanistan (where asafoetida grows widely today) and in India (its biggest modern consumer), its name is far simpler: hing, which derives from the Sanskrit han, meaning “kill”—likely another reference to its deadly uncooked smell.

The word asafoetida is a linguistic meeting of East and West: aza means “resin” or “mastic” in Persian and foetida means “stinking” in Latin. While “stinking resin” seems adequately descriptive, other languages use colorful adaptations of the notion of “devil’s dung” for the spice: şeytan tersi in Turkish; Teufelsdreck in German; dyvelsträck in Swedish; merde du diable in French and esterco-do-diabo in Portuguese. In Afghanistan (where asafoetida grows widely today) and in India (its biggest modern consumer), its name is far simpler: hing, which derives from the Sanskrit han, meaning “kill”—likely another reference to its deadly uncooked smell.

|

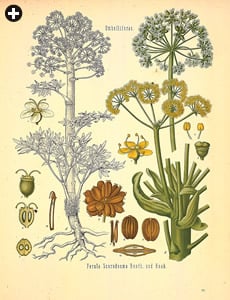

L. MÜELER AND C. F. SCHMIDT, PLATE 147 IN FRANZ EUGEN KÖHLER, MEDIZINAL-PFLANZEN IN NATURGETREUEN ABBILDUNGEN MIT KURZ ERLÄUTERNDEM TEXTE: ATLAS ZUR PHARMACOPOEA GERMANICA... (GERA, 1887)/

MISOURI BOTANICAL GARDEN LIBRARY |

| Although culinary use has been rare in the West since Roman times, asafoetida has held a place in medicine from the eighth century BC in Mesopotamia to a four-volume pharmaceutical atlas, above, published in Germany in 1887. The label uses the older species name, scorodosma, instead of assafoetida. |

Asafoetida is the exudate—technically a mixture of gum and resin—collected from the root of Ferula assafoetida, a relative of the carrot and fennel plants. Today, the plant grows only from eastern Iran to western Afghanistan and in parts of Kashmir, and it has never been successfully cultivated. Generally, a plant must be at least four years old before it will yield, and is tapped in the spring. On finding a suitable plant, a harvester digs away the soil and makes an incision in the top of the thick, carrot-like root, which then exudes, for up to three months, as much as a kilogram (35 oz) of milky resin. The exudate hardens on exposure to air and gradually turns brown. Chemically, the gum resin’s signature pungency is the scent of 2-butyl 1-propenyl disulfide and other disulfides, which break down when subjected to the heat of cooking. Its scent also contains the more pleasant diallyl sulfide, familiar from onions and garlic, which remains intact in cooking, giving asafoetida its distinct, leek-like flavor.

According to Mohammed Shah Rauf, a specialist in sustainable development in rural Afghanistan, much of the asafoetida collected in Afghanistan comes from Herat province near the border with Iran. In Herat, one of the largest asafoetida dealers is Mahmood, who goes only by his first name and who counts among his local customers the Indian consulate, which buys asafoetida from him in bulk. In total, he says his business is “around 2000 kilograms [4400 lb] of asafoetida per year.” Although there are no reliable national statistics, Rauf estimates that Iran and Afghanistan together annually produce approximately 500 to 600 tons of asafoetida. Most is exported to India, since in Iran and Afghanistan it is used only medicinally.

East of Herat, the other major center for asafoetida is in central Afghanistan, in the hills around the provincial capital of Chaghcharan. From there, it is delivered to Kandahar, Afghanistan’s second largest city, and transshipped overland to Quetta in Pakistan and on to India. In Iran, asafoetida is collected in the region around the city of Mashhad and in the rocky highlands southeast of the Dasht-e-Kevir desert.

Chef Yumana Devi mentions in her cookbook Lord Krishna’s Cuisine (1987, Dutton) that in Delhi’s historic Red Fort area, a district of spice-milling shops, “a cloud of the heady asafoetida smell pervades several blocks.” There, the dried asafoetida resin is ground into a powder and mixed with gum arabic and flour, which both keep it from lumping and dilute its intensity. The resulting compound is sold commercially as bandhani hing, several varieties of which can be found in almost any spice market in India, and in North America and Europe on shelves at international groceries, where jars cost a few dollars.

Asafoetida’s popularity in India is not just a matter of taste. Many followers of Jainism avoid eating root vegetables, so they use asafoetida in lieu of onions and garlic. Additionally, some Hindus abstain from onions and garlic, too, particularly in the south, where asafoetida is especially popular. There are also health reasons: Among its medicinal properties, asafoetida is believed to help digestion and counteract flatulence—which is why it is often used with legumes such as chickpeas and lentils.

ealth benefits have been attributed to asafoetida as far back as its culinary history reaches. In the early 11th century, the great physician Ibn Sina recommended it for treating indigestion. Much earlier, in the first century, in his authoritative work on botanical medicine, De Materia Medica, the Greek herbalist Dioscorides recommended it almost as a cure-all: Not only was it good for goiters, baldness, toothache and lung diseases from pleurisy to bronchitis, but asafoetida could also bring on menstruation—a characteristic also attested by Pliny. It could be applied to scorpion bites, and (if one dared) could even “cast[s] off horseleeches that stick to the throat” when “gargled with vinegar.”

ealth benefits have been attributed to asafoetida as far back as its culinary history reaches. In the early 11th century, the great physician Ibn Sina recommended it for treating indigestion. Much earlier, in the first century, in his authoritative work on botanical medicine, De Materia Medica, the Greek herbalist Dioscorides recommended it almost as a cure-all: Not only was it good for goiters, baldness, toothache and lung diseases from pleurisy to bronchitis, but asafoetida could also bring on menstruation—a characteristic also attested by Pliny. It could be applied to scorpion bites, and (if one dared) could even “cast[s] off horseleeches that stick to the throat” when “gargled with vinegar.”

|

Looks can be deceiving: To the uninitiated, the stench of uncooked asafoetida can be memorably revolting. The best way to reconcile with its odor is to learn to cook with it: Sprinkle it lightly—not the whole spoonful!—into warm water, as in the recipe above, or add it to hot oil in a frying pan. Either way, the heat breaks down the disulfides that won it the “devil’s dung” name—and the culinary results have been popular for more than two millennia. |

It is with Dioscorides that we also get the earliest hints of how closely related asafoetida was to my unobtainable Roman ingredient, Cyrenian silphium, because Dioscorides uses the word silphium interchangeably with asafoetida, as if they were varieties of the same plant: “Silphium grows in places around Syria, Armenia, Media [Persia] and Libya.... Though you taste ever so little of the Cyrenian, it causes dullness over your body, and is very gentle to smell, so that if you taste it your mouth breathes but a little of it. The Median and Syrian [varieties] are weaker in strength and they have a more poisonous smell.”

His “silphium” from Syria, Armenia and Persia is almost surely Ferula assafoetida, which does not grow in Libya but which may, in those times, have grown in Syria and Armenia as well as Persia, where it still grows today.

Similarly, the Roman historian Arrian, who is the source of much of our information about Alexander the Great’s expedition to Asia in the late fourth century BC, recounts that in the Hindu Kush mountains of Afghanistan, Alexander’s army found “silphium”—again presumably the ancestor of Ferula assafoetida. It is interesting to know that, 200 years earlier, part of the population of the Cyrenian city of Barce had been deported by the Persians to Bactria—a territory that overlaps the borders of modern Afghanistan, Turkmenistan and eastern Iran—and to speculate that the involuntary migrants might have taken with them the seeds of such a nourishing and medically valuable plant as silphium. In any case, once Libyan silphium ceased to be available, asafoetida from Central Asia turned out to be a convenient substitute.

Open the chicken from the back and arrange it in four sections. Grind pepper, lovage and a moderate amount of caraway seed: Pour fish sauce over them and mix with wine. Place the chicken in a Cumaean clay pot and pour the blended mixture over the chicken. Dissolve fresh silphium in warm water and pour on the chicken as you cook it. Season with ground pepper.

—De Re Coquinaria (On Cookery),

attributed to Apicius

The most likely trade route for asafoetida in Roman times ran from Herat (Roman Aria) northwest to Mashhad (in today’s eastern Iran), where it joined the Silk Roads to follow the southeastern shore of the Caspian Sea, across the Iranian plateau to Ctesiphon, near Baghdad, and then north along the Euphrates to Dura Europos in Syria’s eastern desert. From there, caravans traveled to the Mediterranean either by a northerly route to the port city of Antioch, or a southerly route, via Palmyra and Damascus, to Tyre. In the first centuries of our era, Rome’s new dependence on Asian asafoetida was part of a much greater Roman boom in imported spices. In the words of John Keay, author of The Spice Route: A History, “The spice trade in the early years of the Roman Empire probably exceeded anything seen in the West until the 15th century.”

The fact that Romans had access to Asian asafoetida at all highlights the transcendent economic importance of the spice trade, for the Parthian Empire, which controlled the regions where asafoetida grew, was hostile to Rome’s political ambitions in the East. Nonetheless, the Parthians refrained from disrupting the trade that was the source of their wealth.

With the arrival of Islam in the seventh century, the region where asafoetida grew came to be part of the Abbasid Empire’s Persian territories. Under the Abbasid caliphs, their capital, Baghdad, developed a cosmopolitan court culture. An emerging appreciation of haute cuisine led to a raft of Arabic cookbooks. Best known today is the encyclopedic Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Recipes), dating from the 10th century. Covering everything from condiments to stews, yogurt-based dishes and sweets (along with a chapter on vegetarian entrees), the recipes make use of all parts of the asafoetida plant. The resin (al-hiltit) and root (al-mahrut) are occasionally listed as ingredients, but it is the plant’s leaves (al-anjudhan) that seem to have been most popular in Abbasid cuisine: There is an entire chapter devoted to asafoetida-leaf stews (anjudhaniyya), such as the following:

“Cut meat into thin slices and chop onion and fresh herbs. Put them in a pot and add to them olive oil of excellent quality. When the pot boils and the meat browns, add black pepper, cumin, caraway seeds and a little liquid fermented sauce. Add to the pot crushed asafoetida leaves, as much as needed. Break eggs on the meat and let it simmer for as long as it needs, God willing.”

Asafoetida also appears in kebabs marinated in the ground leaves, along with a vinegar–caraway–asafoetida-leaf dipping sauce, and in a recipe for dried salt fish.

By the mid-13th century, the Mongols had toppled the Abbasids. Their unified rule, the pax Mongolica, guaranteed the relative safety of traders along the Silk Roads. Although there is little evidence that medieval Europeans inherited the Roman use of asafoetida in cooking, it was certainly imported, via Venice, to apothecaries and druggists. It is probably at around this time that the modern word asafoetida was coined by Italian merchants.

few centuries later, the rise of the Mughal Empire in India opened another trade route to another market. Indian food historian S. N. Mahindru points out that, between 1628 and 1658, during Shah Jahan’s rule, “the export trade attained great heights and was diversified. Turmeric, asafoetida and other drugs were the new merchandise that accompanied the earlier exports of pepper, poppy-seed and saffron.” In Agra and Delhi, court singers reportedly ate asafoetida to improve their voices: They would wake before dawn, eat a spoonful of it with butter, and go down to the banks of the river to practice their art at sunrise.

few centuries later, the rise of the Mughal Empire in India opened another trade route to another market. Indian food historian S. N. Mahindru points out that, between 1628 and 1658, during Shah Jahan’s rule, “the export trade attained great heights and was diversified. Turmeric, asafoetida and other drugs were the new merchandise that accompanied the earlier exports of pepper, poppy-seed and saffron.” In Agra and Delhi, court singers reportedly ate asafoetida to improve their voices: They would wake before dawn, eat a spoonful of it with butter, and go down to the banks of the river to practice their art at sunrise.

At that same time, one of the most astute observers of asafoetida’s use in India was Garcia da Orta, physician to the Portuguese governor of Goa for 30 years. A diligent student of botanical medicine, da Orta studied with Indian physicians and yogis as well as with traders who passed through Goa. In Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India (1563), called “the first scientific book on oriental spices published in the western world,” da Orta says:

“You must know that the thing most used throughout India, and in all parts of it, is that Assafetida, as well for medicine as in cookery. A great quantity is used, for every Gentio [Hindu] who is able to get the means of buying it will buy it to flavor his food.... These [people] flavor the vegetables they eat with it, first rubbing the pan with it, and then using it as seasoning with everything they eat. All the other Gentios who can get it eat it, and laborers who, having nothing more to eat than bread and onions, can only eat it when they feel a great need for it.”

Although da Orta was also honest enough to admit that asafoetida had “the nastiest smell in the world for me,” he was also wise enough to observe, “The truth is that there is a good deal of habit in the matter of smells.”

As for me, I still haven’t gotten used to the odor of the raw resin, although the promise of its almost buttery scent when cooked keeps me coming back to it. I still keep it double-wrapped, inside a plastic tub, on the shelf.

|

|

TOP: CHARLES O. CECIL; COINS (2): AMERICAN NUMISMATIC ASSOCIATION |

| Behind the Jabal al-Akhtar (Green Mountain) rising from the coast of northeastern Libya, the Greeks founded Cyrene, where silphium was important enough to earn depiction on the city’s coins. Although the plant resembles asafoetida, “What was silphium?” remains a botanical mystery. |

The disappearance of silphium, around the first century, from Cyrenaica, the promontory of eastern Libya that juts out into the Mediterranean, remains a botanical mystery. By all ancient accounts, the plant grew only there, in the hills and meadows rising from the coastal plain to Jabal al-Akhdar (Green Mountain). Behind the mountain, in 630 BC, Greek colonists founded Cyrene, the city-state that grew rich on its monopoly of silphium.

|

| KYLIX: BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE / ARCHIVES CHARMET / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| Arcesilas II, king of Cyrene from 560 to 550 BC, is shown watching the weighing and loading of silphium for export on a sixth-century BC Greek kylix, or drinking cup. |

Silphium had long been known to the local Amazigh (Berber) peoples of the region, and carvings and pictographs uncovered in Knossos, on Crete, suggest it was also known to the Minoans, probably as a trade good, as early as the second millennium bc. From the Greek nature writer Theophrastus, we know that silphium gum was collected much the same way asafoetida is collected today—by making incisions in the root or lower stalk and gathering the exuded gum.

Like the Greeks, the Romans too prized Cyrenian silphium, although it was clearly becoming a rare commodity. In an attempt to halt the decline, Rome had declared silphium an imperial monopoly, but by the end of the first century the science writer Pliny the Elder declared:

“For these many years past, however, it has not been found in Cyrenaica, as the farmers of the revenue, who hold the lands there on lease, have a notion that it is more profitable to depasture flocks of sheep upon them. Within the memory of the present generation, a single stalk is all that has ever been found there, and that was sent as a curiosity to the Emperor Nero.”

|

| CLASSICAL NUMISMATIC GROUP, INC / WWW.CNGCOINS.COM |

| This tetradrachm, dating from between 485 and 475 BC, shows Cyrene’s eponym, the nymph Kyrene, gesturing toward a silphium plant; her other hand is in her lap. Behind her is silphium’s heart-shaped seed. |

Romans craved silphium not only for its flavor. Historian John M. Riddle, author of Eve’s Herbs (1997, Harvard), cites another reason: “anecdotal and medical evidence from classical antiquity tell us that the drug of choice for contraception was silphium.” In an article with J. Worth Estes in American Scientist, Riddle argues that women in the ancient world regulated conception with drugs, and that this may even have been the most important use of silphium and the reason for its great value: “Silphium’s sap may have been the ancient world’s most effective antifertility drug.” In recent laboratory experiments, their article claims, some asafoetidas have inhibited conception in rodents.

The shape of the silphium seeds, which we know only from their depiction on Cyrene’s coins, reinforces this link to fertility: The seeds were distinctly heart-shaped—the same heart shape we see in modern western culture associated with romantic love, despite its lack of resemblance to the anatomical human heart. Thus, some researchers have speculated that this symbol of romance derives from the silphium seed.

One of our most important sources on Roman cuisine is a cookbook from the late Roman Empire titled De Re Coquinaria (On Cookery). Many of its recipes call for silphium as a base seasoning (see “Parthian Chicken,” page 41), and it includes instructions on “How to make one ounce of silphium last indefinitely.” (Store it in a closed jar with pine nuts, which absorb the flavor. Use and replenish the pine nuts, keep the silphium.) By then, Roman cooks must already have been using asafoetida as a substitute. Yet there are tantalizing hints that Cyrenian silphium in fact survived. For example, there is a letter written by the Christian bishop of Cyrene in the fifth century in which he thanks his brother for the silphium cuttings sent from his garden.

Some scholars have proposed that Ferula tingitana, a relative of Ferula assafoetida that grows wild across North Africa, the Levant and the Iberian Peninsula, is in fact silphium. (Cyrenian silphium is unrelated to the modern plant genus Silphium, which includes more than 400 species, mostly in North America.) However, in the early 1990’s, Italian archeologist Antonio Manunta of the University of Rome found in Cyrenaica specimens of Cachrys ferulacea, which grows wild from Sardinia to Uzbekistan. Bedouin in Cyrenaica believed it to be the same as silphium, based on the images on Cyrenian coins, and they took Manunta to a valley with abundant Cachrys ferulacea in the exact areas where silphium once flourished. Additionally, the oil from the seeds has a pleasant smell, which matches Dioscorides’ statement that Libyan silphium didn’t have the strong odor of asafoetida. But for Manunta, the strongest piece of evidence was the seed: Of all the seeds of plants hypothesized to be silphium’s descendants, it’s the only seed that is heart-shaped.

|

Chip Rossetti (jrosse@sas.upenn.edu) was a senior editor for the American University in Cairo Press and is now a doctoral student in Arabic literature at the University of Pennsylvania. His revised edition of the National Geographic Traveler Egypt guide will be published in October. |

|

Michael Nelson (masrmike@gmail.com) is the Middle East regional photo manager for the European Pressphoto Agency (EPA) in Cairo. |