![Saturday, December 26, 1914: Behind [the Prince] stood the Emir Nawwaf, extending both his hands to me; followed by a long line of my old, loyal friends, all of whom I embraced and kissed before entering the tent. Nawwaf seated me between himself and his father and from all sides there poured upon me greetings and inquiries after my health. Among these good people I felt at home—among brothers. —Alois Musil, In the Arabian Desert](/issue/200906/images/musil/intro-text.gif)

|

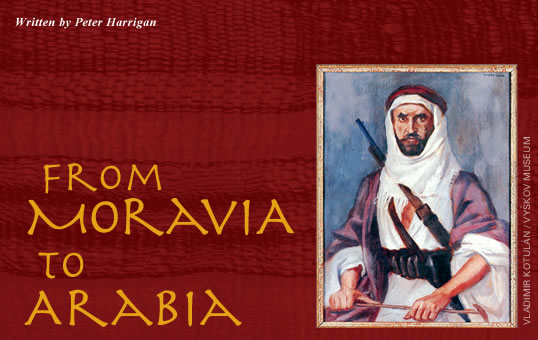

| VYŠKOV MUSEUM |

| Musil traveled with a glass-plate camera, and he made this image of Ruwala Bedouin while the tribe rested in Wadi Sirhan, near the modern border of Jordan and Saudi Arabia. In the center is Prince Nuri ibn Hazza ibn Sha‘lan, who became one of Musil’s closest friends. |

started out collecting beetles in Czechoslovakia and ended up a professor of Arabic,” says Rudolf Veselý, explaining his career shift from entomologist to orientalist half a century ago. “The adventures of a certain remarkable Austrian–Czech inspired me.”

started out collecting beetles in Czechoslovakia and ended up a professor of Arabic,” says Rudolf Veselý, explaining his career shift from entomologist to orientalist half a century ago. “The adventures of a certain remarkable Austrian–Czech inspired me.”

|

| PETER HARRIGAN |

| This bust and plaque commemorating Musil as a professor and orientalist hangs on the wall outside the Vyškov Museum. |

I am with Veselý and his longtime colleague, emeritus professor Luboš Kropáèek, in Prague, in the library of the Institute of Near Eastern and African Studies at Charles University, on Celetná Street near the historic heart of the Czech capital. Veselý and Kropáèek are sharing their recollections of Alois Musil, explorer, professor, author, prelate, general and honorary tribal shaykh, whose 72-year life ended in 1944. Though Musil was broadly, even spectacularly, accomplished, he remains among the least known of the 19th and early 20th centuries’ explorer-scholars of Arabia and the Levant—though that may be about to change.

Today, even most Czechs are unaware that, in addition to his almost monumental scholarly output, Musil penned more than 20 popular books for young people about desert adventures in Arab lands. Veselý remembers being one of his avid young readers. “I was enthralled by his vivid descriptions and thought, ‘What a region to collect beetles from!’ Then I happened to meet a Czech entomologist who had collected beetles from Palestine,” he recalls. “We collaborated, and I found that, having read Musil’s books, I already knew the areas where he had collected. My interest in the Middle East took off, and I decided to study Arabic.”

Musil’s books similarly inspired Kropáèek, especially during the dark days of World War II and the onset of the Communist regime in 1948, when Musil gave his young readers an unbounded world brimming with adventure. Kropáèek believes that Musil’s “accurate and culturally sensitive accounts of Arabs…pushed fantasy pictures of the Arab East to the margin” and “contributed to the growth of sincere interest in Oriental studies among young Czechs.”

The professors reel off highlights of Musil’s achievements: 21,000 kilometers (13,000 mi) of desert journeys on camelback; more than 50 books, including six illustrated tomes published by the American Geographical Society; some 1200 scholarly articles; more than 500 transcribed, translated tribal poems and songs; thousands of photographs of archeological sites, landscapes, people and Bedouin encampments; topographic maps and surveys of territories previously unseen by westerners; the sensational discovery of Qasr ‘Amra, now a World Heritage Site; and—not least—a plant named after him: Thymus musilis. They add that if scholastic integrity was the warp of his work, then his respect for Arab people was the weft, and today, Musil’s sense of the value of understanding among nations, cultures and religions still feels fresh, even prescient. In a paper published in Archiv Orientalni, Kropáèek wrote, “Virtually all that [Musil] has written…on various aspects of Muslim culture attests to a great deal of sympathy. Those who remember him confirm that in private conversation also he used to speak well of Islam.” Indeed, Musil himself wrote, “I have met people of different professions, nationalities and religions. I considered all to be good, and trusted everyone.”

|

|

| VYŠKOV MUSEUM (2) |

| Left: Musil’s portrait of Emir Nawwaf, who, with his father Ibn Sha‘lan, gave Musil the tribal title “Sheikh Musa Rweili.” Right: Musil recorded countless details of daily life, including the making of adobe bricks in Al-Jawf, in northern Saudi Arabia.

|

The professors welcome the new interest in Musil, as shown especially by recent international scholars’ conferences in Prague and Vienna and the 2008 founding of the Academic Society of Alois Musil. In a more popular vein, the Moravian town of Vyškov, near his birthplace, five hours by train southeast of Prague, celebrates “Alois Musil Days” each year with lectures, reenactments on horseback and plenty of Arab food and music.

It was in a farm cottage that still stands near Vyškov, in the village of Rychtářov, that Alois Musil was born in 1868, the oldest of a peasant couple’s five children. He did well in school, studied theology at Olomouc University—where he took an interest in Near Eastern languages and Old Testament studies—and at 23, like many peasant sons in Hapsburg lands, entered the Catholic priesthood. Two years later, in 1895, he received a doctoral degree and left for further studies at the new École Biblique et Archéologique Française de Jérusalem (the French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem). There, during long treks in and around the city, he came to realize that his plans for study in archeology, geology and the origins of monotheistic religions could not be fulfilled without better understanding of the land and people—the topography and ethnography—of the region. In 1897 Musil left for Beirut, where the library at Saint Joseph University was attracting students of the region’s history, languages, literature, geography and archeology.

But the lure of the desert meant that Musil frequently skipped lectures. His fascination with field studies caused so much tension in the Catholic hierarchy back home that, after failed attempts to recall him, his financing was withdrawn. Musil turned to other sources for support, first to Vienna’s Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften (Imperial Academy of Sciences), which thus became the first of a long list of patrons that eventually included Hapsburg royalty, Bedouin tribal leaders, the first president of Czechoslovakia (and his American wife), Austro-Hungarian and Czechoslovak academics, Ottoman functionaries and a Chicago industrialist.

The year 1898 marked the start of what became the first of Musil’s three long phases of travel. He explored the eastern shores of the Dead Sea and the plateau region of Moab as well as Petra, Palmyra, Sinai and Gaza. In Madaba, Jordan’s “City of Mosaics,” he heard that, in the lawless country to the east, there stood a ruined building filled with magnificent early-Islamic frescoes. The Bani Sakhr tribe, headed that way to raid the Ruwala, offered to take him there.

What followed was his most acclaimed achievement as an explorer: The modern discovery of the eighth-century Umayyad lodge Qasr ‘Amra and the frescoes that indeed covered its plaster walls and triple-domed ceilings.

But his visit was brief: Attack was imminent. “I enter and see remnants of paintings everywhere. I run from room to room; all are painted. I understand the importance of my discovery and thank God,” he wrote in Tajemná Amra (Mysterious Amra), published in Prague in 1932.

“I want to take pictures and I take the first photograph. My companion, lying on the roof, shouts, ‘Our foes, Musa, our foes.’ I hide my camera and we gallop toward the east. Three or four riders pursue us from the north.”

“Musa”—as he was called by the tribesmen, who changed “Musil” to the Arabic name for Moses—managed to take fuzzy photographs, but the plates were lost in his flight. Despite the risks he had taken, when he returned to Vienna his report of frescoes that showed a ruler on a throne and Arcadian scenes of plants, animals and hunting provoked incredulity: Representation, his skeptics argued, was an unlikely element of early Islamic art. There were no known references to these frescoes in Arab literature, and no other western travelers who had been in the area had even heard of the site or anything like it. “Not even my priesthood or my academic titles could save me

from accusations of being a liar,” Musil wrote.

It took two subsequent visits, in 1900 and 1901, and more than 100 photographs, to vindicate his claims and set right his reputation. On the 1901 trip, he was accompanied by the Austrian artist Leopold Alphons Mielich, who copied the frescoes, and he also brought back plaster fragments removed from the walls, some of which are now in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

Back in Vienna from his third visit to Qasr ‘Amra, Musil started writing up his journeys. In 1907 the Imperial Academy of Sciences published Kuseyr Amra in two lavish elephant-folio volumes. Musil also published maps with some 3000 toponyms from Petra and the surrounding area.

The next year, again under the auspices of the Viennese Academy, Alfred Hölder published Musil’s four-volume, 1633-page Arabia Petraea, containing ethnological observations, hundreds of illustrations, an extensive bibliography and a map supplement. It was the fruit of Musil’s observations made on camel- and horseback as he traveled to Sinai, Aqaba, Gaza, across the plateau of Moab and south to Petra, the Nabataean capital that lends its name to the region of the title.

The next year, again under the auspices of the Viennese Academy, Alfred Hölder published Musil’s four-volume, 1633-page Arabia Petraea, containing ethnological observations, hundreds of illustrations, an extensive bibliography and a map supplement. It was the fruit of Musil’s observations made on camel- and horseback as he traveled to Sinai, Aqaba, Gaza, across the plateau of Moab and south to Petra, the Nabataean capital that lends its name to the region of the title.

As well as writing in German, Musil wrote and was published in Czech, English and Arabic. By his own count, he was fluent in 15 modern and classical languages, including Greek, Syriac, Aramaic and Hebrew, and from his long desert journeys he had an intimate grasp of tribal vernacular. His skill came from tireless study and practice, and Musil expected the same from others. Kropáèek tells a story of Musil interviewing Anna Blechová, who would become his dedicated personal assistant until his death. ”How many languages do you have?” Musil asked Blechová. “Six,” was her reply. “Six is not enough,” retorted Musil. “You will have to study harder”—but he hired her.

Veselý laughs as he continues the theme: “Musil was a captivating lecturer, a methodical scientist and ethnographer, but when it came to actually teaching Arabic to his students, he was just too demanding. He would chalk up the Arabic alphabet, tell his students to learn what he had written and then leave. Next session he would carry in Arabic tomes and expect students to read from them. No wonder they complained!”

|

|

|

| VYŠKOV MUSEUM (3) |

| Far left: The popular Czech painter Zdeněk Burian illustrated the cover of Musil’s Syn Pouště (Desert Son), published in Prague in 1933, a year after Tajemná Amra (Mysterious Amra), whose cover shows the eighth-century Umayyad

lodge Musil “discovered” in 1898. Above, right: Arabia Petraea, published in four volumes in 1908, helped Musil win recognition as an explorer, geographer, ethnographer, scientific observer and cartographer. |

With his first works published, Musil’s reputation grew beyond German-speaking continental Europe. He was now recognized as an accomplished explorer, geographer, ethnographer, scientific observer and cartographer. Recognition enabled him to continue to cultivate as patrons an assortment of institutions, intellectuals and luminaries, Catholic clerics, military officials of the Austro-Hungarian establishment and aristocrats of both Europe and the desert.

At 40, he embarked in 1908 on his second phase of exploration. Over the next decade, five journeys would take him into deserts from the Tigris to settled Syria, east to Baghdad and into the northern parts of Najd and the Hijaz in what is now Saudi Arabia. Many of the areas were cartographic blanks, never before traversed by occidental explorers.

With a surveying assistant, Rudolf Thomasberger of the Military Geographical Institute of Vienna, Musil sought out the Ruwala tribe in its often-contested domains that now sprawled across the boundaries of emerging states. Just as in his first series of journeys, when he cultivated the friendship and support of the Bani Sakhr, Musil now gained the trust of the Ruwala paramount chief—Prince Nuri ibn Hazza ibn Sha‘lan—and formed a friendship that would endure a lifetime and win him the honorary title “Shaykh Musa al-Ruwayli.”

During his journey in the winter of 1909, Musil accompanied the migrating Ruwala under Ibn Sha‘lan. “A strange dispensation of Allah,” Musil commented, “for a Bedouin prince to be riding beside a Czech at the head of a big tribe!” He later wrote that, when he reminded the prince of this, he received Ibn Sha‘lan’s reply: “Allah has willed it. I never thought I should make friends with a man whose blood is not mine. Do not forget me, Musa, when you ride at the head of your tribe!”

Musil did not forget. The last and crowning title in his series of six English-language volumes, Oriental Exploration and Studies, is The Manners and Customs of the Rwala Bedouins. In his six-paragraph preface to the 712-page ethnography, Musil thanks Ibn Sha‘lan alongside barons, archbishops and professors.

Despite his own responsibilities for the welfare of his community, Ibn Sha‘lan showed remarkable patience toward Musil’s constant photographing, surveying and notetaking, and his penchant for spending days writing in his tent, which more than once delayed the tribe’s migration. Musil described how, one evening in the prince’s tent, dining on hares coursed by a saluki and killed by his falcon, Ibn Sha‘lan, in the customary manner, tossed Musil the best pieces of meat. Musil wrote: “When I urged him not to forget himself since he, as our head, must keep himself strong in order to take care of us all, he replied that he cared most for his best freebooter, that is, his brother Musa. He called my scientific expeditions ‘raids.’” Since raiding was a favored sport among the Ruwala, the comment revealed both Ibn Sha‘lan’s wit and his tolerance toward what likely appeared to him to be Musil’s noble yet obsessive quest.

Maps were a major fruit of Musil’s “raids”—sketch maps, horizon profiles and larger folding maps separately cased are the distillate of his tireless topographical investigations. He and Thomasberger deployed their equipment at regular intervals to establish latitude and to

Maps were a major fruit of Musil’s “raids”—sketch maps, horizon profiles and larger folding maps separately cased are the distillate of his tireless topographical investigations. He and Thomasberger deployed their equipment at regular intervals to establish latitude and to

survey from vantage points. Then, to fill in the detail of areas not covered on the ground, Musil would interview guides and those familiar with the territory, crosschecking so as not to rely solely on a single informant. (See “Equipment and Observation,” sidebar above.)

In the desert, Musil was never far from danger, and he was forthright with his companions. Challenged by a youthful chief famous for courage as to whether he had fears rambling alone in the desert, Musil answered, in the presence of other chiefs, “What is fear, O Mamduh? What is the unknown desert? I was roaming through it on a camel’s back when you were being carried through it in a saddlebag.” The face of his youthful interrogator flushed and he retreated, recalled Musil, explaining for the reader that young boys rode in saddlebags until they were old enough to sit on a camel. Later, Ibn Sha‘lan would recognize Musil’s courage with lines in an ode composed in his honor:

… a hero who fears not vast deserts

Who is to carry word to countries far and distant

After his adventures with the Ruwala, Musil returned to Europe and took up a professorship at the University of Vienna. But he was soon back in the camel saddle, making good use of his desert connections in what became the third phase of his travels. He set out in 1910 under Ottoman authority to focus on geological and hydrological surveys east of the Jordan River and along the Hijaz Railway. Two years later, in 1912, he again set off from Austria to Mesopotamia, ostensibly on a grand tour and hunting expedition, accompanied by Prince Sixtus

Bourbon-Parma, whose sister Zita was later to become the wife of Emperor Charles, the last ruler of the Hapsburg Empire. Sixtus made Musil an honorary general, and on this trip they were in fact searching for mineral deposits and other resources in connection with a planned railroad link from Berlin to Basra. Back in Vienna, Sixtus confessed that he had traveled into the desert with Musil as a prince, but returned as a man. For Musil, friendship with Sixtus became another deeply personal connection: Musil’s niece—mother of Jana Štelclová—was named Zita, after Sixtus’s sister.

As World War I broke out in 1914, Musil became increasingly embroiled in his sponsors’ foreign-policy interests. That year, at the request of Emperor Franz Josef, he undertook a diplomatic mission to Arabia. In 1917, he made his last expedition to Turkey, Asia Minor, Syria and Palestine with Archduke Hubert Salvator, a medical doctor and cavalry general in the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Army. Their official purpose was to inspect field medical units and check on the safety of Austro-Hungarian citizens in Ottoman territories. But with the imminent collapse of both the Hapsburg and the Ottoman Empires, there are differing interpretations of Musil’s role: One is that he went to dissuade Arab tribes from fighting against the Ottoman occupation; another, more nuanced, view is that he sought to strengthen the Austrian position within the Ottoman provinces as the Turks shed territory and to actually encourage the Arabs in their uprising against the Ottoman occupation (famously aided in the field by T. E. Lawrence). His loyalty, it seemed, was to neither the Germans nor the Ottomans, but to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and specifically to the Hapsburgs.

Although these efforts proved futile, given the outcome of World War I, Kropáèek asserts that Musil was ahead of his time, because in addition to being “a tireless driving force in encouraging commercial ties,” he was committed to “developing relationships and cultural links between the West and the Arabs based on trust and mutual respect.” This, he maintains, was “very farsighted.”

In 1918, his desert journeys over, Musil left Vienna, opting for citizenship in the new Czechoslovakia, and with it a new post as professor of Oriental studies and Arabic in the department of philosophy at Charles University, where Veselý and Kropáèek work today.

|

| PETER HARRIGAN |

| In 1918, Musil returned to his native village of Rychtářov, to a house he named “Villa Musa,” which remained his home until 1938. |

There followed 25 years of prodigious scholarly output, drawing on his journeys as well as Arabic literature and western scholars. Musil made trips to America (see “The American

Connection,” sidebar above) to prepare his books in English. It was during this time that he wrote his

popular adventure titles in Czech, as well as a scholarly series dealing with the national

awakening in the new Arab states. All his writings show a strong anticolonial stance and

support for genuine Arab independence and autarky.

By 1938, the area around Musil’s home, “Villa Musa,” in Rychtářov was occupied by German troops. Musil retired from academia, left his country home and relocated to a small farm near Otryby. There he remained largely secluded, absorbed in studies, writing and tending his smallholding.

By 1938, the area around Musil’s home, “Villa Musa,” in Rychtářov was occupied by German troops. Musil retired from academia, left his country home and relocated to a small farm near Otryby. There he remained largely secluded, absorbed in studies, writing and tending his smallholding.

“He particularly loved fruit trees and beekeeping,” says Štelclová, who, like her great-uncle, spends time gardening when not in her practice or preparing her lectures. “On all his journeys he carefully observed desert plants, collected botanical specimens and was concerned about problems of desertification. In his later years he wrote regularly on farming in the Czech agricultural press.”

Musil’s secretary, Anna Blechlová, tracked all the books, journal and newspaper articles and maps that he published, as Musil kept writing until his death. In Blechlová’s 50-page list of his publications, running from 1896 to 1944, only 1919 lacks an entry: a brief period immediately following the founding of the Republic of Czechoslovakia in October 1918.

|

|

|

| VLADIMIR KOTULÁN (2) |

| The Academic Society of Alois Musil was established in 2008, and in April of this year, a plaque was erected (top) on the house in Otryby, near Prague, where Musil spent his last days in 1944. Above: Few of Musil’s belongings survive from his desert journeys, but among the few is his treasured camel saddle, displayed in the Alois Musil Hall at the Vyškov Museum. |

Today, nearly 66 years after his death, with attention focused on dialogue between the West and the Arab world, there is new interest in the legacy and work of Alois Musil.

In July 2008, Abdullah Al-Askar, professor of history at King Saud University in Riyadh, presented a paper on Musil and cross-cultural understanding in which he argued that Musil should be given greater prominence as a role model for positive dialogue between nations. “Those around him did not have to be replicas of himself and his society before he could see, recognize, talk and be at ease with them,” says Al-Askar, who is also a member of the Saudi Majlis al-Shura (Consultative Council). “He wanted what was good for them—self-determination and modernization—first and foremost if not exclusively.”

Garth Fowden, author and researcher at the Institute of Greek and Roman Antiquity in

Athens, offers another modern perspective in his recent account of research at Qasr ‘Amra: “Born a Moravian Czech, and always aware of belonging to a subject people, [Musil] was able

to see himself as a devoted Austrian or, once the Austro-Hungarian Empire broke up, a loyal citizen of Czechoslovakia—but above all, and always, as an Arab,” he wrote. “And an Arab, for Musil, was one who lived in everyday communion with the realities of human existence, from the struggle for survival in a hard land to the intuition, in the desert’s abstract landscape, of God’s simplicity.”

To Al-Askar this makes Musil not just a “prolific intellectual”

to be admired in one of history’s spotlights, but a man whose work and attitudes are “of immediate relevance today and into our futures.”

|

Peter Harrigan (harrigan@fastmail.fm) is a visiting researcher for the “Maritime Ethnography of the Arabian Gulf and Red Sea” project at the Institute of Islamic and Arab Affairs at Exeter University. For this article, he visited Prague and Moravia in the Czech Republic as well as Jordan, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, remarking that “even using motorized transport, following Musil’s 21,000 kilometers of saddleback desert travel would be next to impossible.” |