|

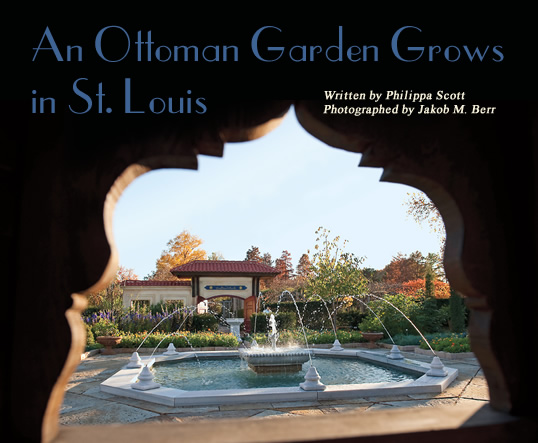

| As in historic Ottoman gardens, at the center of the Bakewell Ottoman Garden is a shallow pool (havuz), with a fountain. |

here is something about a walled garden that suggests a world set apart, special and secret. Enclosed, inward-looking, the walled garden lends itself to poetic imagery and metaphors for the spiritual world: Here is a safe place for introspection. Birdsong, the sight and sounds of water, the sweet smells of flowers—all have powerful and beneficial effects on our minds and emotions: The garden offers us its haven.

here is something about a walled garden that suggests a world set apart, special and secret. Enclosed, inward-looking, the walled garden lends itself to poetic imagery and metaphors for the spiritual world: Here is a safe place for introspection. Birdsong, the sight and sounds of water, the sweet smells of flowers—all have powerful and beneficial effects on our minds and emotions: The garden offers us its haven.

Gardens, like nature, are never static. They change not only with weather and seasons, but also with the vagaries of human tastes and fashions from age to age and place to place. From the 17th to the 19th century, some of the world’s most renowned gardens were created by the Ottomans in Turkey.

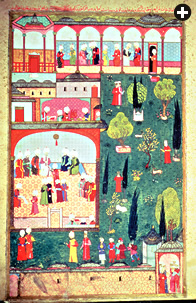

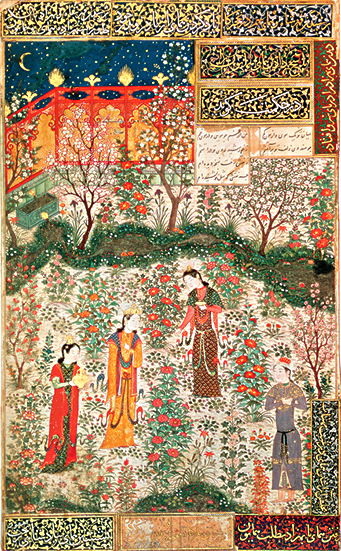

Paintings, manuscripts, palace records, travelers’ descriptions and merchants’ account books all provide much information about them. Travelers especially marveled at the Ottomans’ love of gardens, remarking that, at court, to be presented with a choice bloom was deemed a high compliment, and the flower itself was worthy to be worn with, or instead of, a turban jewel. Visitors described the abundance of flowers in the Ottoman market gardens, and one source warned that selling tulip bulbs anywhere but in the capital, or exporting too many, were offences punishable by exile.

Paintings, manuscripts, palace records, travelers’ descriptions and merchants’ account books all provide much information about them. Travelers especially marveled at the Ottomans’ love of gardens, remarking that, at court, to be presented with a choice bloom was deemed a high compliment, and the flower itself was worthy to be worn with, or instead of, a turban jewel. Visitors described the abundance of flowers in the Ottoman market gardens, and one source warned that selling tulip bulbs anywhere but in the capital, or exporting too many, were offences punishable by exile.

hen he died in December 1993, Edward L. Bakewell, Jr. of St. Louis, Missouri left funds to his heirs to create in his name a public garden within the city’s Missouri Botanical Garden. In planning to carry out his wishes, his sons Ted and Anderson remembered their father’s fascination with a family legend that connected them to the Ottoman world, rekindled by his visit to Istanbul many years ago. They felt that this offered both a fitting theme for their father’s bequest as well as a practical complement to the Botanical Garden’s existing horticulture.

hen he died in December 1993, Edward L. Bakewell, Jr. of St. Louis, Missouri left funds to his heirs to create in his name a public garden within the city’s Missouri Botanical Garden. In planning to carry out his wishes, his sons Ted and Anderson remembered their father’s fascination with a family legend that connected them to the Ottoman world, rekindled by his visit to Istanbul many years ago. They felt that this offered both a fitting theme for their father’s bequest as well as a practical complement to the Botanical Garden’s existing horticulture.

The legend had endured through the family’s maternal line, which counts among its ancestors Marie Marthe Aimée Dubucq de Rivéry, who lived in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and—if the story is to be believed—became not only a wife of an Ottoman sultan, but also the mother of another. (See “The Legend of Aimée,” opposite.) Because of this, the Bakewell Ottoman Garden, dedicated in May 2008, was inspired by descriptions and images of gardens from this era. Together with the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Japanese and Chinese gardens, the Ottoman Garden enables the Botanical Garden to present experiences in both Far Eastern and Near Eastern gardens, in addition to its American and European traditions.

|

| bibliothÈque nationale / giraudon / bridgeman art library |

| Depicting a late 17th-century Ottoman garden party hosted by the Queen Mother (Valide Sultan) for Madame Girardin, wife of the French ambassador, paintings such as this provide valuable insight into Ottoman garden design. |

n Istanbul, the first three decades of the 18th century, under the reign of Ahmet iii, became known as the “Tulip Era.” Tulip festivals grew in popularity, and the influence of French rococo spread through the decorative arts and architecture, a result of the sultan’s embassy to the French court at Versailles. Called lâle in Turkish, tulips are the most famous Turkish flower, long popular as a design motif in textiles, ceramics, paintings and even architecture. In Ottoman calligraphy, the word Allah was often written in the shape of a tulip. At the zenith of their horticultural art, the florists of the Ottoman court bred delicately colored tulips with long, slender petals and an elongated almond shape, and these refined flowers earned display singly, each in its own long-necked vase.

n Istanbul, the first three decades of the 18th century, under the reign of Ahmet iii, became known as the “Tulip Era.” Tulip festivals grew in popularity, and the influence of French rococo spread through the decorative arts and architecture, a result of the sultan’s embassy to the French court at Versailles. Called lâle in Turkish, tulips are the most famous Turkish flower, long popular as a design motif in textiles, ceramics, paintings and even architecture. In Ottoman calligraphy, the word Allah was often written in the shape of a tulip. At the zenith of their horticultural art, the florists of the Ottoman court bred delicately colored tulips with long, slender petals and an elongated almond shape, and these refined flowers earned display singly, each in its own long-necked vase.

Europeans were fascinated by this new flower from the East, which they first classed as a sort of red lily. There are several claims regarding the tulip’s introduction to European gardens. When extraordinary streaked tulips first appeared in Dutch gardens, the result was “tulipmania,” and the Dutch turned the Ottoman love of flowers into an obsession in which fortunes were made and lost. (There was no way of telling whether a tulip bulb would result in a single-color bloom or a far more valuable one with color breaks. We now know that Potyvirus creates the streaked, feathered appearance, and today’s tulips have been extensively hybridized to make the most of this effect.) A school of Dutch flower painting developed, and portraits of these new flowers themselves became symbols of wealth. To the Dutch, the flowers resembled the exotic sea shells, minerals and marbles that wealthy collectors sought to display in the “cabinets of wonders” popular at the time.

he creation of an Ottoman garden in Missouri is possible because of the general similarity of St. Louis’s climate to that of northwestern Anatolia, especially the cities of Bursa, Istanbul and Edirne. Each was at one time the capital of the Ottoman Empire, and each had extensive imperial gardens, as well as scores of others that provided places of intimate association with nature and family within the confines of domestic complexes.

he creation of an Ottoman garden in Missouri is possible because of the general similarity of St. Louis’s climate to that of northwestern Anatolia, especially the cities of Bursa, Istanbul and Edirne. Each was at one time the capital of the Ottoman Empire, and each had extensive imperial gardens, as well as scores of others that provided places of intimate association with nature and family within the confines of domestic complexes.

Both Istanbul and St. Louis lie at approximately 40 degrees latitude, although Istanbul enjoys milder Mediterranean weather, while St. Louis endures a more extreme continental climate. Although many of the same plants will flourish in each, a few substitutions had to be made for the Bakewell garden. For example, the Mediterranean cypress (Cupressus sempervirens) does not flourish in continental climates, and so, to achieve an Ottoman “alley” or arboreal passageway, Jason Delaney, Missouri Botanical Garden’s senior horticulturist, planted a row of red cedar along the pathway, unified, in the Ottoman manner, by rosemary between and at the bases of the trees.

|

| The inscription above the garden’s entrance translates, “Praise to the Benefactor, praise.” |

Covering some 1000 square meters (1/4 acre), and designed around a traditional Ottoman reflecting pool, the Bakewell

garden is a window into the gardens and gardening practices that evolved across the Islamic world. From its inception, this has been the heart of the Bakewell Ottoman Garden project, and the garden’s educational focus fosters understanding of Turkish history during an era when many now-familiar plants, shrubs, trees and flowering bulbs were first introduced to the West. Not only plants, but some familiar

garden and park architecture also has Ottoman origins: Bandstands in many a park, including Henry Shaw’s gazebos in St. Louis, New York’s Central Park and London’s Hyde Park, all owe their designs to Turkish

Covering some 1000 square meters (1/4 acre), and designed around a traditional Ottoman reflecting pool, the Bakewell

garden is a window into the gardens and gardening practices that evolved across the Islamic world. From its inception, this has been the heart of the Bakewell Ottoman Garden project, and the garden’s educational focus fosters understanding of Turkish history during an era when many now-familiar plants, shrubs, trees and flowering bulbs were first introduced to the West. Not only plants, but some familiar

garden and park architecture also has Ottoman origins: Bandstands in many a park, including Henry Shaw’s gazebos in St. Louis, New York’s Central Park and London’s Hyde Park, all owe their designs to Turkish

garden kiosks (köşks), which in turn derive from tents and pavilions. The 18th-century European fashion for turqueries included garden follies in the form of Ottomanesque tents and tented “smoking rooms” with Ottoman-style divan seating. Still today, throughout even rural Anatolia, simple kiosks—small, raised, roofed structures, open-sided, built of stone and wood—offer any passing shepherd or wanderer a place to rest, enjoy a view or picnic.

|

| TopkapI palace museum / dost yayInlarI / giraudon / bridgeman art library |

| An Ottoman miniature by Lokman, from the late 16th century, shows a council of ministers in an elaborate palace garden. |

stanbul was built on the hills of what is today the European side of the city. The other shore marks the beginning of Asia, and between these flows the Bosporus, whose waters allow ships from the Mediterranean and beyond to sail via the Marmara Sea to the Black Sea. The Byzantine city was in disrepair long before 23-year-old Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror besieged and captured it in 1453. Travelers describe scenes of sad desolation, and even the Great Palace, built when Constantine first founded his city, lay in ruins. Once resplendent, with palaces, villas and terraced gardens sloping down the hillsides to the Bosporus shore, and market gardens inside the city walls, it never recovered from its sacking and occupation in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade, spearheaded by the Venetians. After 1453, the Ottoman Empire lasted some 500 years until 1923, when the modern Republic of Turkey was established.

stanbul was built on the hills of what is today the European side of the city. The other shore marks the beginning of Asia, and between these flows the Bosporus, whose waters allow ships from the Mediterranean and beyond to sail via the Marmara Sea to the Black Sea. The Byzantine city was in disrepair long before 23-year-old Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror besieged and captured it in 1453. Travelers describe scenes of sad desolation, and even the Great Palace, built when Constantine first founded his city, lay in ruins. Once resplendent, with palaces, villas and terraced gardens sloping down the hillsides to the Bosporus shore, and market gardens inside the city walls, it never recovered from its sacking and occupation in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade, spearheaded by the Venetians. After 1453, the Ottoman Empire lasted some 500 years until 1923, when the modern Republic of Turkey was established.

The last contemporary historian of medieval

Byzantium, Michael

Critobulus, tells us that,

in the course of Mehmet’s rebuilding, “Around the palace he laid out a circle of large and beautiful gardens, burgeoning with various fine plants, bringing forth fruits in season, with abundant streams, cold, clear and good to drink, studded with beautiful groves and meadows, resounding and chattering with flocks of singing birds that were also good to eat, pasturing herds of animals both domesticated and wild.”

|

| The garden’s St. Louis-based lead architect, Fazil Sütşü, was born and educated in Turkey. |

|

| The garden’s Ottoman sundial is calibrated to show Islamic prayer times. |

A portrait of Mehmet by Siblizade Ahmet, now in the Topkapi Palace collection, depicts him not as a warrior or a ruler, but peaceably seated, delicately inhaling the scent of the rose he holds in his hand.

All Islamic gardens share an underlying theme of Paradise, nourished by the River of Life. Thus in a garden, a fountain and pool symbolize the pool in Paradise into which the celestial rivers flow. The basic elements—an open pavilion, a geometric layout and a water system that both nourished the garden and produced sound—were all familiar to most peoples of the greater Middle East. The climate of Anatolia did not demand the same rigorous irrigation practices as, for example, Iran. There the qanat system of underground

water channels developed, which was well suited to the formal

garden, with four sections divided by straight water courses; nonetheless, in certain parts of Anatolia settled by Seljuk Turks, who arrived by way of Iran, the influence of this type of garden may

be traced to that country.

ttoman gardens developed in roughly three categories: those dominated by a pavilion and closely associated with water; those geometrically laid out, usually around a fountain; and informal gardens that emulated nature with minimal human contrivance, or natural situations discreetly adapted to enhance human enjoyment.

ttoman gardens developed in roughly three categories: those dominated by a pavilion and closely associated with water; those geometrically laid out, usually around a fountain; and informal gardens that emulated nature with minimal human contrivance, or natural situations discreetly adapted to enhance human enjoyment.

|

|

|

|

| The garden is designed to harmonize relationships among flora, architecture, color, light, scent and sound. Frescos, top, use motifs taken from Ottoman manuscripts. The crescent-shaped finials atop both the pavilion’s copper dome (top right) and the kuşevi (birdhouse, above right) open upward to evoke tulip petals. Above: A detail of one of the garden’s main doors highlights the rich red ochre, or “Ottoman rose,” that was the royal color of the Ottomans. |

An ideal Ottoman garden, given the space to do so, would incorporate each of these aspects. The Ottomans and their Turkic cousins, the Timurids, harking back to their nomadic ancestry, cherished no less the informal, natural-style garden. These often shared elements with game parks, and in the larger ones, gazelles, rabbits, birds and other creatures were hunted, and archery was practiced. Ottoman paintings show gazelles and rabbits—the original lawn mowers—cropping the grass in gardens that combine fruit trees, flowers grown alongside vegetables, shade trees and the ubiquitous cypresses that stretch skyward like slender Ottoman minarets. Meandering paths led to benches and other places for repose, and where these seemed appropriate—for instance, next to a palace, pavilion, road or canal—more formal, well-ordered plots of flowers, shrubs and trees were planted. Sometimes a vine-covered pergola provided shade. If the space was enclosed with a trellis, this was most frequently painted in red ochre, or “Ottoman rose.” Whereas purple had been the royal color of the Byzantines, it was red that held significance for the Turks, even before their conquest of the city they nicknamed “the Red Apple.” Constantine’s great Church of Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, was converted into a mosque and painted in red ochre, as were many of the wooden water-side mansions, or yalıs, built along the Bosporus, some of which can still be seen today.

An ideal Ottoman garden, given the space to do so, would incorporate each of these aspects. The Ottomans and their Turkic cousins, the Timurids, harking back to their nomadic ancestry, cherished no less the informal, natural-style garden. These often shared elements with game parks, and in the larger ones, gazelles, rabbits, birds and other creatures were hunted, and archery was practiced. Ottoman paintings show gazelles and rabbits—the original lawn mowers—cropping the grass in gardens that combine fruit trees, flowers grown alongside vegetables, shade trees and the ubiquitous cypresses that stretch skyward like slender Ottoman minarets. Meandering paths led to benches and other places for repose, and where these seemed appropriate—for instance, next to a palace, pavilion, road or canal—more formal, well-ordered plots of flowers, shrubs and trees were planted. Sometimes a vine-covered pergola provided shade. If the space was enclosed with a trellis, this was most frequently painted in red ochre, or “Ottoman rose.” Whereas purple had been the royal color of the Byzantines, it was red that held significance for the Turks, even before their conquest of the city they nicknamed “the Red Apple.” Constantine’s great Church of Holy Wisdom, Hagia Sophia, was converted into a mosque and painted in red ochre, as were many of the wooden water-side mansions, or yalıs, built along the Bosporus, some of which can still be seen today.

|

| Under the hand-painted dome sits a wooden “throne,” carved in Turkey for the garden, based on historic designs of seats that were easily transportable for use at events held in gardens. |

In capturing Byzantine territories, the Ottomans also inherited Byzantine gardening customs, which had in turn developed from the classical world of Greece and Rome. Conversely, in Renaissance Italy, gardens that attempted to recreate classical tastes ended up sharing much in common with Ottoman gardens. In this way, Byzantium provided a connection among such different cultures and periods as ancient Greece and Rome, Persia and the world of Islam, as well as serving as a bridge between late antiquity and the Renaissance. Although it has been argued that much of the Renaissance built upon the splendors of the Islamic East, history is rarely so simple, as the arts of the Renaissance would not have been possible without the Chinese technologies, such as silk and papermaking, introduced to the West by way of Muslim cultures along the Silk Roads.

The Ottoman regard for gardens and flowers ultimately extended far beyond the garden walls. The great buildings of Sinan, the most renowned architect of the Ottoman era, are decidedly Ottoman not only in their form but also in their decorations, which rely often on floral motifs. Similarly, flowers shimmer on tiled surfaces on the walls of mosques, palaces and public baths; huge tulips undulate on caftans of silk and gold; steel armor and horse trappings gleam with damascened blossoms. Foreigners remarked, in letters home, on the Turks’ love of flowers. Several varieties of narcissus (nergis) are native to Ottoman lands, and these, as well as roses (gül), carnations and pinks (karanfil), hyacinth (sümbül) and almond blossom (badem), came to comprise the Ottomans’ “four-flower” motif in the mid-16th century.

|

| bibliothÈque nationale / bridgeman art library |

| For all their later influence on the West, Ottoman gardens themselves had been much influenced by both Byzantine gardens and gardens from other Islamic lands—notably Persia, where this miniature shows a walled garden in the 15th century. |

he entrance to the Bakewell Ottoman Garden is through double doors surmounted by a gabled terra-cotta roof. Beneath this are panels of specially made Iznik tiles bearing calligraphic inscriptions. Facing the approaching visitor, Ottoman script proclaims Al hamd li wali al hamd, “Praise to the Benefactor, praise.” Then, as the visitor completes a visit and approaches the gateway to leave, the interior panel offers the last line of a contemporary poem by Turkish musician and writer Kudsi Ergüner, which translates, “The Benefactor awaits the reach of your memory within the garden.”

he entrance to the Bakewell Ottoman Garden is through double doors surmounted by a gabled terra-cotta roof. Beneath this are panels of specially made Iznik tiles bearing calligraphic inscriptions. Facing the approaching visitor, Ottoman script proclaims Al hamd li wali al hamd, “Praise to the Benefactor, praise.” Then, as the visitor completes a visit and approaches the gateway to leave, the interior panel offers the last line of a contemporary poem by Turkish musician and writer Kudsi Ergüner, which translates, “The Benefactor awaits the reach of your memory within the garden.”

Facing the entrance stands an Ottoman sundial whose calibrations also indicate Islamic prayer times. Beyond this, a shallow reflecting pool, or havuz, has a central fountain and small jets of water along its edge. Many old Ottoman houses were built with special rooms known as havuz odası, literally “pool room,” in which a large raised pool in the center was surrounded by divans along the walls. This is, of course, a pleasant and practical form of natural air conditioning.

|

| Plantings mix trees, shrubs, herbs and flowers to create a naturalistic appearance adapted to St. Louis’s climate. |

To the right stands a pedestal fountain (çeşme), which invites visitors to rinse their hands in its cool water. Similarly, on the back wall of the raised patio, opposite the entrance, a wall fountain (selsebil) adds further soft tinkling sounds as water drops from its tiers. All were made for the Bakewell garden by Turkish craftsmen using Turkish marble. It was the custom in Turkey for people to be greeted on arrival and blessed on departure with water, and in Ottoman times, every house and garden had fountains at entrances and exits.

Opposite the garden’s entrance, in the spirit of a kiosk or pavilion, stands a covered, raised, paved patio with a wooden grape arbor (çardak). Its roof has a copper-topped central dome, intricately painted inside. Outside, it is surmounted by a brass finial (alem), in this instance not a crescent, which is reserved for mosques, but a stylized tulip. From here, the visitor looks down on the reflecting pool and across to the entrance, viewing the garden from a raised perspective.

Several stone birdhouses invite feathered visitors to rest and linger, and at the back of the covered arbor, to either side of the wall fountain, painted panels, with floral designs copied from Ottoman manuscripts, decorate the wall. Ottoman interiors were often decorated with painted scenes, murals of flowers, like these, or views of terraced gardens with kiosks, seascapes, imaginary scenes or versions of what might in fact be seen outside.

Several stone birdhouses invite feathered visitors to rest and linger, and at the back of the covered arbor, to either side of the wall fountain, painted panels, with floral designs copied from Ottoman manuscripts, decorate the wall. Ottoman interiors were often decorated with painted scenes, murals of flowers, like these, or views of terraced gardens with kiosks, seascapes, imaginary scenes or versions of what might in fact be seen outside.

Under the dome, in front of the gently dripping wall fountain and at the top of the patio steps, stands a wooden throne with gilded details, which is quickly appreciated by visitors who enjoy being photographed “like a sultan.” This too was handcrafted in Turkey, where wooden thrones such as these were transportable items, set out in kiosks and pavilions, along with rugs and pillows, so the sultan and members of the court could enjoy music and poetry, picnics and feasting in comfort outdoors.

|

| Leaving the garden, visitors pass under the inscription that translates, “The Benefactor awaits the reach of your memory within the garden.” |

Many of the flower species commonly known to Ottomans are recognized today in subspecies or hybridized forms, and the garden includes plants known to be the closest to their Ottoman varieties. Huge “Ali Baba” earthenware pots are planted with tender shrubs, pomegranate, jasmine and lemon, so that they can be taken indoors in winter, just as in Ottoman gardens tender plants wintered inside the limonluk, or conservatory, which was also used for forcing spring bulbs. The garden’s size dictates certain limitations, and so columnar fruit trees have been planted here, their upright growths echoing the cedar alley that flanks the walkway opposite. The plants will mature, growing and spreading; the architectural elements will mellow; and season to season, the garden will whisper its perennial invitation: The Benefactor awaits the reach of your memory within the garden.

|

Philippa Scott (philippa.scott1@gmail.com) is a freelance author and journalist specializing in the arts and cultures of the Middle East. She is the author of Turkish Delights (Thames & Hudson, 2001) and a contributing editor to Hali, the magazine devoted to Islamic textiles and art. She lives in London. |

|

Jakob M. Berr (www.jakob-berr.com) is a freelance photo-journalist and Fulbright scholar finishing a master’s degree in photojournalism at the University of Missouri School of Journalism in Columbia, Missouri. |