n late September, the seaside town of San Vito lo Capo, on the westernmost tip of Sicily, becomes a culinary center of the Mediterranean world. Against a backdrop of serrated mountains, its streets of dazzling whitewashed buildings fill for a week with the aromas of the Orient and the rhythms of the Maghreb. Stalls draped with multicolored banners line boulevards and alleyways, displaying steaming mounds of that tiny-grained, wheat-based North African staple, couscous.

n late September, the seaside town of San Vito lo Capo, on the westernmost tip of Sicily, becomes a culinary center of the Mediterranean world. Against a backdrop of serrated mountains, its streets of dazzling whitewashed buildings fill for a week with the aromas of the Orient and the rhythms of the Maghreb. Stalls draped with multicolored banners line boulevards and alleyways, displaying steaming mounds of that tiny-grained, wheat-based North African staple, couscous.

|

| Food stalls line the streets during the weeklong Cous Cous Fest. This one offers couscous from North Africa as well as organic couscous. |

The only global event of its kind, the Cous Cous Fest has been held in San Vito lo Capo annually since 1998 to celebrate the peoples, traditions and flavors of the Mediterranean. In addition to crowds of local and foreign aficionados, it brings together chefs from around the region who vie to create the year’s top couscous dish. The adjudicators of the contest, who usually include cookery writers, restaurateurs and the director of the prestigious Gambero Rosso food guide, look for the best blend of colors and tastes, which this year they found in the lamb couscous of the Tunisian delegation.

For Girolamo Turano, president of Sicily’s Trapani province, which includes San Vito, the Cous Cous Fest means more than food. It’s “a symbol of peace, brotherhood and integration among ethnic groups across the Mediterranean,” he says. And he doesn’t mean just a European Mediterranean: Chefs from Italy, France, Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Palestine and Israel—as well as from Senegal and the Ivory Coast—all come together in San Vito. Alongside the formal competition is a cultural festival, a carnival of music, dancing and eating celebrating Sicily’s place at the crossroads of the Mediterranean.

|

| Winner of the festival’s culinary contest in 2006, local chef Domenico Castiglia prepares one of his gourmet seafood couscous dishes by first hand-rolling durum wheat into tiny grains. |

|

| Later, he gets ready to steam it over a fish broth and serve it with a stew of local fish and vegetables, left. His finished dish appears at the top of the article. |

To modern European eyes, Sicily is on the margins of the continent, an island outpost. But throughout most of its history, Sicily was a hub of the Mediterranean world, invaded and settled successively by Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Normans and Spaniards, each attracted by the island’s climate and fertility, who came, saw and conquered in their turns before Sicily’s unification with mainland Italy in 1860.

The Arab invaders and settlers were, specifically, Aghlabids from the north coast of Africa. Arriving first in 827, they landed at Mazara del Vallo, not far south of San Vito along the island’s western coast. From Mazara they gradually spread east, and in 965 they established the independent Muslim emirate of Sicily. Until the Normans invaded in 1061—and even afterward, thanks to the Normans’ open-minded recognition of Arab accomplishments —the island was a center of Arab science, medicine, philosophy and law, and a conduit through which cultural, artistic and culinary influences flowed throughout the continent.

Even today, the west of Sicily is where the Arab influence is most strongly felt. The Sicilian dialect of Italian contains numerous words of Arabic origin, and it’s no accident that many of them relate to food or agriculture, such as zibbibbu (a grape variety, originally zabib in Arabic) and cafisu (a liquid measure, originally qafiz). Some words have passed via Sicily into standard Italian, such as zaffarana (saffron), sorbetto (sorbet, originally sharbaat), carciofi (artichoke, from al-khurshouf) and zucchero (sugar, from sukkar). Sugarcane was one of the crops the Muslims introduced to Sicily, along with the citrus fruits that flourish here today.

Besides crops, the Muslims introduced better methods of cultivating them. They improved the island’s irrigation systems with techniques developed in their drier homelands, and created intensively farmed smallholdings. The ensuing fertility was noted by one of Sicily’s first travel writers after the Norman invasion: Andalusian civil servant and chronicler Ibn Jubayr.

|

| “Land... such as we had never seen before for goodness, fertility and amplitude,” was how Ibn Jubayr in 1185 described the

Sicilian interior. |

Ibn Jubayr was shipwrecked off Sicily’s east coast in 1185, on his way back from the pilgrimage to Makkah. He traveled through the island to the west, from where he eventually caught a boat back to Spain. First noting Sicily’s “Mountain of Fire” (the volcano Etna), he wrote that “the prosperity of the island surpasses description. It is enough to say that it is a daughter of Spain in the extent of its cultivation, in the luxuriance of its harvests, and in its well-being, having an abundance of varied produce, and fruits of every kind and species.”

Ibn Jubayr was shipwrecked off Sicily’s east coast in 1185, on his way back from the pilgrimage to Makkah. He traveled through the island to the west, from where he eventually caught a boat back to Spain. First noting Sicily’s “Mountain of Fire” (the volcano Etna), he wrote that “the prosperity of the island surpasses description. It is enough to say that it is a daughter of Spain in the extent of its cultivation, in the luxuriance of its harvests, and in its well-being, having an abundance of varied produce, and fruits of every kind and species.”

He marveled at the mountains “covered with plantations bearing apples, chestnuts and hazelnuts, pears and other kinds of fruits,” and when nearing Trapani on the west coast he observed “land, both tilled and sown, such as we had never seen before for goodness, fertility and amplitude.” Ad-mirers of the civilization they inherited, the Normans had adopted and preserved many of the Arab agricultural techniques, some of which are still apparent in the Sicilian landscape today.

|

| Though seafood remains central to Sicily’s economy and cuisine, these boats have lain idle since the imposition of restrictions on tuna fishing. |

It’s likely that couscous formed part of the Sicilian Muslim diet, as well as its better-known close cousin, pasta, which is thought to have been developed by the Arabs and brought to the Italian mainland by way of Sicily. The earliest known mention of large-scale pasta production is found in Al-Kitab al-Rujari (Roger’s Book), written in 1154 by the geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi. Surveying Sicily, he noted “a fertile plain and vast farms, where they manufacture itriya [thin strands of pasta] in such great quantity as to supply both the towns of Calabria and those of the Muslim and Christian territories as well, to where large shipments are sent.”

The word couscous derives from the Maghrebi Arabic kuskusu, and the Sicilian cuscus has long existed in both folk memory and the kitchens of Sicily’s western Arab heartland. It is via the Maghreb, however, that couscous is flourishing again in Sicily, reintroduced by migrants from North and West Africa who have settled on the island during the last few decades. Sicilians have enthusiastically revived the dish, cooking it more often with fish than with meat (usually mutton), which would be more usual in the Maghreb.

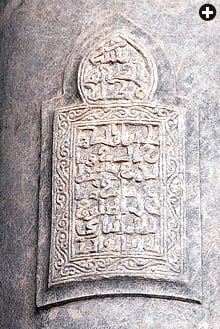

|

| One of the few concrete reminders of what were once more than 300 mosques, a lone Arabic inscription of the Fatihah, or opening verse of the Qur’an, remains on a pillar in Palermo’s cathedral. |

Domenico (“Mimmo”) Castiglia is one of the younger generation of chefs who have embraced the new fare. Now 39, he became interested in couscous when traveling in North Africa, even venturing as far afield as Brazil, where a couscous is made with cassava, or manioc-root, flour—a legacy of the African slave trade. But it was from a vechietta (“an old lady”) back in Mazara del Vallo that Mimmo first learned to make the dish that is now the specialty of his restaurant and that in 2006 won him first prize in the Cous Cous Fest.

In the spotless kitchen of his Ristorante da Mimmo in the north coast town of Finale di Pollina, Mimmo is busy preparing the ingredients to make his signature prize-winning fish couscous. He does this in the time-honored—and very time-consuming —way, as learned from the households of North Africa, where making couscous can take all day, from first rolling out the grains to putting the finishing touches on the plate, the women lightening their work with conversation.

It takes Mimmo most of a day, too. First he puts the durum wheat flour (semola di gran duro, also thought to have been introduced to Sicily by Arabs) into a bowl and adds water. He begins to mix it with his hands. “It’s like a meditation,” he says as he blends, adding more water a little at a time. “You have to do it slowly—piano, piano—until the pieces separate and become grains of the same size.”

|

| Hot peppers, called pipareddù in Sicilian, at the market in Palermo, Sicily’s capital, are popular throughout Sicilian cuisine. |

Then he lays the couscous grains on a wooden board to dry. Later, he adds them to a pan suspended above a simmering fish broth, where they steam for two hours, expanding and absorbing the fish flavors. Finally, he drains away the broth and covers the grains with a wool blanket for a further six hours. Only then does he add a zuppa di pesce (fish stew) and serve it with a salsa piccante on the side. It’s clear from the precision with which Mimmo works that he loves couscous and that he’s absorbing new culinary practices as readily as the grains soak up

his broth.

|

Couscous, traditionally, is a dish for sharing. It is a carbohydrate into which proteins and vegetables are mixed, depending on the fare available locally. In Sicily’s past, as still in many regions of Africa, it was a staple of the everyday diet—filling, nutritious and economical, humble or festive depending on which ingredients accompany the base. In Sicily, it has moved from the tables of contadini (peasant farmers) and migrants to the most sophisticated of restaurants, becoming a truly cross-cultural dish.

|

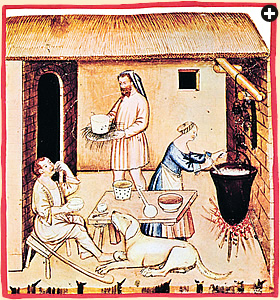

| Wikimedia Commons |

| The making of ricotta cheese, which may have begun in Sicily, is shown in this 14th-century illustration. |

A few miles along the coast from Mimmo’s restaurant is the fishing town of Cefalù. Dominated by a huge crag known as La Rocca, the town has ancient origins: On La Rocca’s summit are the remains of a Greek temple, which later became a Byzantine fortress and then an Arab citadel. It was the Normans who built the duomo, the Romanesque cathedral that squats under La Rocca and forms a focal point for Cefalù’s citizens and tourists alike. Each evening at sunset, they gather in the Piazza del Duomo to eat a gelato, or sip a caffè or aperitivo under the palms.

On the corner of the piazza is the Bar Duomo, which sells a large selection of another of Sicily’s specialties: the hand-made paste (pastry biscuits) that are also such a feature of Italian life. Like Greeks and Levantines, Sicilians are known for their partiality to sweet foods, a fondness with its origins among the Arabs, who introduced sugarcane to the island. When the Normans arrived, the confectionery industry was so well established that it was deemed in need of regulation, and from then on, Sicily became associated with the production of sweets—especially those made with ricotta, pistachio and marzipan, such as are on display in the windows of the Bar Duomo.

|

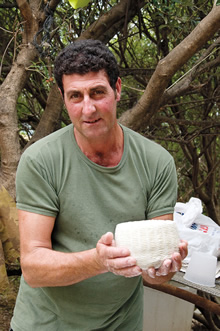

| Today, handcrafted ricotta, left, is the base for one of Sicily’s Arab-rooted sweets, cassata siciliana. |

Gleaming under the spotlights, the paste di mandorla (marzipan candies) are delicately fashioned in the shapes of pears, apples, peaches and even watermelon slices. The Italian word marzapane (marzipan) is of Arab origin (marsaban), and the sweet itself is thought to have been invented in Persia, arriving in Europe via the Mediterranean to Sicily, or via North Africa to Spain—or both. In Sicily, it’s a recipe that has been passed down from generation to generation.

Indeed, the owner of the Bar Duomo, Giovanni Serio, learned how to fashion the paste from his father, making the marzipan in his kitchen using almonds grown in Sicily’s south and flavored with extracts of fruits and flowers. He shapes the almond paste by hand or presses it into molds before painting each one with natural food colorings and glazing them with gum arabic.

Now Serio has taught his own son the family recipe, as well as that for another characteristically Sicilian dessert with

Arab roots that sits chilling in the bar’s cool cabinet. Cassata siciliana is a rich, creamy confection that takes its name from the Arabic qas’aht, the word for a large bowl. It’s in this bowl that a sponge cake, sweetened ricotta cheese and marzipan are molded before being iced and decorated—with a rather baroque flourish—with pieces of

candied fruit.

|

| A creamy, molded confection of ricotta mixed with sweetened almond paste, or marzipan. |

|

| Pure marzipan comes in shapes and sizes limited only by the confectioner’s imagination. These are shaped like bite-sized tomatoes. |

Like the paste di mandorla and cannoli—another celebrated dessert of Arab origin (a brittle shell of fried dough filled with sweetened ricotta cheese and candied fruit)— it’s likely that cassata passed from the households of Muslim Sicily into the island’s Norman monasteries and aristocratic houses as a treat to be shared at holidays. In the convents of Palermo, the recipes were carefully preserved and refined, providing the nuns with a profitable sideline in sweets for the households of wealthy merchants or aristocrats.

In both cassata and cannoli, the main ingredient is ricotta, a soft, creamy goat or sheep cheese made from re-cooked whey (hence the name ricotta); it is thought to have been invented in Sicily by either Greeks or Arabs. There are what may be mentions of ricotta in Greek literature, though the first more certain reference to making ricotta appears in the illustrated manuscript Tacuinum Sanitatis (The Maintenance of Health), a 14th-century Latin translation of the 11th-century Arabic Taqwim al-Sihha by physician Ibn Butlan of Baghdad.

In both cassata and cannoli, the main ingredient is ricotta, a soft, creamy goat or sheep cheese made from re-cooked whey (hence the name ricotta); it is thought to have been invented in Sicily by either Greeks or Arabs. There are what may be mentions of ricotta in Greek literature, though the first more certain reference to making ricotta appears in the illustrated manuscript Tacuinum Sanitatis (The Maintenance of Health), a 14th-century Latin translation of the 11th-century Arabic Taqwim al-Sihha by physician Ibn Butlan of Baghdad.

Quite apart from the medical and dietary advice, the manuscript comes alive through its vivid portrayals of scenes from medieval domestic life. In the depiction of ricotta-making, a woman stirs milk in a blackened cauldron with a long wooden spoon, while a bearded man carries a finished cheese to a circular basket on the table. A seated man samples the cheese as a hungry dog looks on. It’s a scene still played out today in the pastures of the Madonie Mountains of central Sicily, some 700 years later.

|

|

| Lemons, another staple crop first cultivated by Arabs, are so popular that they are not only a top granita ingredient, but a popular symbol of Sicily itself. |

In a meadow near the village of Sant ’Ambrogio, a shepherd named Giulio Cangelosi comes every morning to tend his goats. When there is enough grass for them to eat, he makes ricotta in the old way, milking the goats by hand and heating the milk in a large smoke-blackened pot over a wood fire. The tuma (curds) are the product of the first cooking process, which he ladles into baskets—just as in the Tacuinum Sanitatis.

Next, he reheats the remaining siero (whey), adding more milk and stirring the liquid with a wooden stick until it solidifies: This is the re-cooking, the ricotta. He was taught the method by his parents, but nowadays, he explains, people are not interested in learning. “You have to get up very early to make ricotta,” he says, “and you make hardly any money.” Giulio says he makes it because he loves the freedom of being in the countryside, selling a few cheeses to local shops and giving the rest to his friends.

Giulio’s ricotta is made with the same attention to detail that Mimmo gives to his couscous, and that Rosario (“Saro”) Garbo gives to the granita at his restaurant not far down the road. Granita is a slushy concoction based on finely ground ice, making it a close relative of another Arab legacy, sorbetto (sorbet). Until the invention of the refrigerator, the main ingredient in Sicilian granita was the snow from Mount Etna, pockets of which endure throughout the hottest of Sicilian summers, sweetened with fruit syrups.

The name granita is widely believed to be due to its granular consistency. It can be flavored with coffee, almond, cinnamon, mulberry or that Arab favorite, jasmine. By far the most popular granita, though, is made with lemons. Saro only uses the best for his recipe—a greenish variety called verdello, one of the citrus varieties introduced by the Arabs and now grown so extensively in Sicily that the lemon has become a symbol of the island. It and other picturesquely named citruses—femminello, monacello, sanguinella—are sold in the markets of each village and town, above all in the street markets of Palermo, the ancient capital of the Sicilian Muslim emirate.

The name granita is widely believed to be due to its granular consistency. It can be flavored with coffee, almond, cinnamon, mulberry or that Arab favorite, jasmine. By far the most popular granita, though, is made with lemons. Saro only uses the best for his recipe—a greenish variety called verdello, one of the citrus varieties introduced by the Arabs and now grown so extensively in Sicily that the lemon has become a symbol of the island. It and other picturesquely named citruses—femminello, monacello, sanguinella—are sold in the markets of each village and town, above all in the street markets of Palermo, the ancient capital of the Sicilian Muslim emirate.

For Ibn Jubayr, traveling through Norman-ruled Sicily, Balarm (Palermo) was “the metropolis of these islands … combining the benefits of wealth and splendor,” he wrote. “It dazzles the eyes with its perfection.” In its heyday, Palermo was said to have 300 mosques, and although the only trace of a mosque now is a single inscription in Arabic on a single pillar at the cathedral’s entrance, in other ways, Ibn Jubayr might still feel at home here today.

|

| Now resonant with voices from North Africa as well as the island itself, Sicily’s markets continue to be hubs of the cultural exchanges that are celebrated each September at the Cous Cous Fest. |

Even now, the markets of Capo, Vucceria and Ballarò feel more Arab than European, and they have occupied these same Palermo streets for the past 1000 years, filling the Sicilian air with the sights, smells and sounds common in the suqs from Syria to Morocco: the same kaleidoscopic patchworks of colorful vegetables, pungent spices, peppery herbs and glittering fish; the same shadowy workshops with their craftsmen tapping metals and planing wood; the same urgent calls of the market traders with goods to sell before the day is done.

And among their calls are words that Ibn Jubayr would surely have recognized: Mixed with the Sicilian dialect are words in throaty Arabic, for a new generation of North Africans is settling here, bringing with them old and new traditions, old and new ingredients to mix into the cultural and culinary stew that Sicily was, and still is. Exactly like a steaming plate of couscous, in fact.

|

Historian and travel writer Gail Simmons (www.travelscribe.co.uk) holds a master’s degree in medieval history from the University of York. Before becoming a full-time travel writer for British and international publications, she surveyed historic buildings and led hikes in Italy and the Middle East. |

|

A photographer and writer, Tor Eigeland (www.toreigeland.com) has covered assignments around the world for Saudi Aramco World and other newspapers and magazines, and has contributed to 10 National Geographic Society book projects. |