|

| Above,

threads of silk and cotton seem to pour

and swirl in intricate, hand-stitched

embroidery designs of beads, disks,

sequins, glass, crystals, lace and their

own patterned and built-up stitching:

It's all "precious goods"—maal. |

edrolls and suitcases line the workshop's walls, but their owners are

not likely to get much sleep, nor will they be visiting their families

back in West Bengal and Bihar anytime soon. Nor is the

overhead television turned on, as it might be if a cricket match

were being played and work were slow. Only the day's several

tea breaks interrupt the breakneck schedule.

edrolls and suitcases line the workshop's walls, but their owners are

not likely to get much sleep, nor will they be visiting their families

back in West Bengal and Bihar anytime soon. Nor is the

overhead television turned on, as it might be if a cricket match

were being played and work were slow. Only the day's several

tea breaks interrupt the breakneck schedule.

In coming weeks, brides, grooms and their extended families

from many of India's top socialite families will depend

on these men to finish bedecking their wedding garments in

a manner that, in a former time, would have well pleased even

the most demanding prince or rajah. For design partners and

workshop owners Abu Jani and Sandeep Kholsa, this is as

it should be: Indian pride in the famous Indian art of embroidery, which they

have done much to foster.

Abu and Sandeep have placed Indian

embroidered garments, such as the shervani (knee-length coat fitted closely at the

waist), the gote (wide, flared pajama pants),

the ghagra (multi-panel wedding skirt), the

dupatta (stole-like head covering) and the

kurta and kurti (long and short tunic), on

Hollywood red carpets and Mayfair runways—

not to mention in Bollywood itself and

at the lavish parties of New Delhi industrialists.

Their Mumbai shop, in smart Kemps

Corner, sells saris for $9000 and shervanis

for $16,000. For a single wedding, some 50

garments might be sold to one family for the

several daytime and nighttime appearances

|

|

The art of Mughal-style embroidery starts

with an abundance of raw materials, from

a profusion of ornamental maal above to

thread, below, that varies by material, weight

and color. |

|

Yet for 37-year-old embroiderer Rehmat

Shaikh, a married man with a young son

in his West Bengal village four hours from

Calcutta, his monthly salary of 8000 rupees

($200) seems like decent pay. His brother

working on the railroad back home makes

much less, he says, and risks his life every

day. Shaikh meanwhile takes pride in his

precise and artful work. "I know no less

than 1000 different designs," he says, not an

unreasonable number given the great variety

of embroidery pieces—in metal, cotton,

silk, plastic, glass and Swarovski crystal, all

known collectively as maal, literally meaning

"material" or "stuff," but here with

the connotation of "precious goods"—that

he applies to the fabric with different stitches

and knots.

François Bernier, the French physician in Mughal emperor

Aurangzeb's court, wrote of much the same work 300 years

ago in his Travels in the Moghal Empire:

"Large halls are seen in many places, called

karkanahs, or workshops for the artisans. In

one hall, embroiderers are busily employed,

superintended by a master." He continued,

"[M]anufactures of silk, fine brocade, and

other fine muslins, of which are made turbans,

girdles of gold flowers, and drawers

worn by females, so delicately fine as to wear

out in one night" might cost up to 10 or 12

crowns, "or even more when embroidered

with fine needlework."

But in at least one way, things have

changed. Bernier noted, "In this quiet and

regular manner, their time glides away, no

one aspiring to any improvement in the condition

of life wherein he happens to have

been born. The embroiderer brings up

his son as an embroiderer." No more: Shaikh's

father was a farmer, and Shaikh wants

his own son to grow up to work as an

it

man in an office in Bangalore. Perhaps due

to the globalized garment trade and to the

growth of India's middle class, both at home

and abroad, whose members can afford

fine embroidery work, many more workers

have entered the embroidery trade than

in previous generations, and it seems likely

that many kinds of office work will be available

to the generation that will follow.

|

|

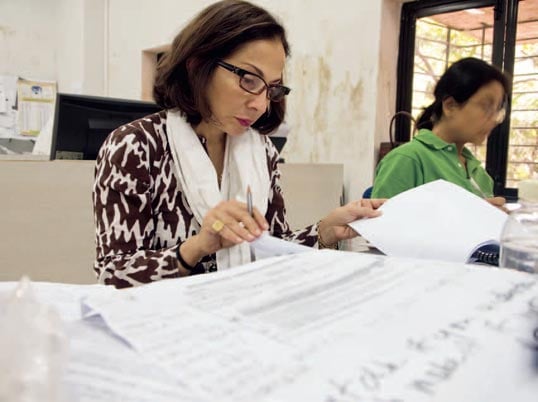

| Shamina Talyarkhan,

founder of Shameeza Embroideries, reviews

orders from New York, which are then listed

on an erasable board. |

Shaikh's specialty is zardozi. This uses

a straight needle with cotton or silk thread

in a cross-stitch, often to apply all varieties

of maal, frequently in gold and silver, to the

fabric. Zardozi is a highly creative art and

may use nothing more than colored threads

to create organic or geometric designs,

sometimes couched over a paper cutout

called a wasli to raise the pattern or runstitched

along the folds of a pleated metallic

ribbon, called gota, to create the veins and

ribs of a leaf or petal. The craftsman can

also freely modulate both the length of the

stitch and its orientation on the fabric, crosshatch

the stitching alternately on the diagonal

or use French knotting to vary shimmer

and smoothness.

|

|

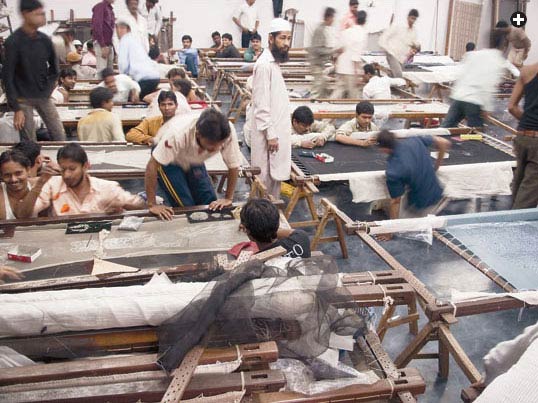

Working four, five or six to a frame, young craftsmen often choose the embroidery

trade in pursuit of upward mobility. |

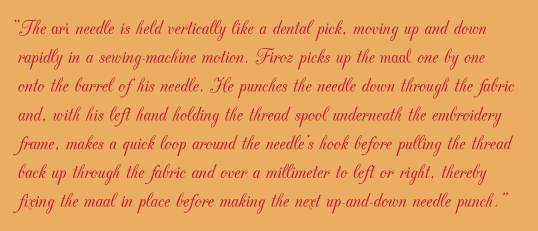

Abu's and Sandeep's 33-year-old floor

supervisor is soft-spoken Firoz Malik, who

can lend a hand with the workshop's other

main embroidery technique, ari, which is done with the same

kind of hooked needle used in French tambour lace-making,

itself a craft of Eastern origin. Firoz's eighth-grade education is

considered advanced for a man in the needle trade.

The ari needle is held vertically like a dental pick, moving

up and down rapidly in a sewing-machine motion. Firoz

first picks up the maal one by one onto the barrel of his needle.

He punches the needle down through the fabric and, with his left

hand holding a spool of thread underneath

the embroidery frame, makes a quick loop

around the needle's hook before pulling the

thread back up through the fabric and over

a millimeter left or right, thereby fixing the

maal in place before making the next upand-

down needle punch. The ari needles are

of different sizes, depending on whether the

thread is single, double or triple, and according to

the diameter of the holes in the sequins and beads

that are being attached.

|

|

During the height of the wedding season,

many sleep in the shop at night and each

morning place their bedrolls on overhead

shelves. |

Ari work goes faster than zardozi, but if it's

done carelessly, the chain stitch on the underside

of the fabric can unravel if the thread is broken in

any one place. Having to tie stop knots to mend it

breaks the rhythm and jars the smooth, fast lines

that ari is known for, so embroiderers must get

it right the first time. A flower pattern measuring

10 by 25 centimeters (4 x 10") might take an ari man

15 hours, which is about half the time of a zardozi

job of the same area.

Both ari and zardozi embroidery work are said

to be of Persian origin and were perfected under the

Mughals. An even finer Persian embroidery called

chikan kari reached nearperfection

under the nawabs of Awadh in

the 19th century; that has been revived and

brought to an even higher level by Abu and

Sandeep. Using untwisted cotton thread on

cotton fabric in white and off-white tones,

chikan work is known for its 35 unique

stitches, including shadow (applied underneath

the fabric, so the top side is smooth

yet shaded from below); jaali (separates the

warp and weft threads into bundles of four

within a reinforced perimeter, thereby making

screen-like perforations in the fabric);

and murri (shaped like grains of puffed rice).

Each one is simple yet very elegant. The

chikan workers are all village women, and

they do not work with the men in Mumbai:

They work in a haveli, or country house,

outside Lucknow.

|

Abu and Sandeep's design department is

staffed with recent graduates of India's top

fashion institutes, all with a practical, problem-

solving outlook. One recent project was

to lighten a Rabari-style coat—traditionally

made by that tribe in the Kutch area of Gujarat—

which uses glass mirrors stitched into

place in a mosaic pattern. But such work is

impractical for modern wear and impossible

to drape attractively. The designers replaced

the glass with metal foil in different hues,

thus achieving the same reflective quality,

broadening the color palette and at the same

time lightening the wearer's shoulder load

enormously.

In the 16th century, in the time of the

Mughal emperor Akbar, his vizier Abu al-

Fazl ibn Mubarak wrote in the Ain-i Akbari,

a logbook of his emperor's reign:

His majesty pays much attention to

various stuffs; hence Irani, European,

and Mongolian articles of wear are

in much abundance…. The imperial

workshops in the towns of Lahore,

Agra, Fatehpur, Ahmedabad and

Gujarat turn out many masterpieces

of workmanship, and the figures and

patterns, knots and variety of fashions

which now prevail astonish experienced

travelers.… [A] taste for fine

material has since become general,

and the drapery used at feasts surpasses

every description.

|

In central Mumbai, Shamina

Talyarkhan has long astonished even the

most experienced travelers with her eye for

fashion. Recently named by Time magazine

as one of the world's top businesswomen in

the luxury trade, she remembers how she

started in the 1970's. Freshly arrived in

New York, wearing saris and lugging suitcases

of embroidered dresses up and down

Fifth Avenue, she found disappointment.

"They didn't buy," she says, "but I learned

something important—how to design and

sell embroidered pieces to famous couturiers—

people like Valentino, Yves Saint

Laurent, Escada, Ralph Lauren and Reem

Acra—so they could fit them into their

own creations."

|

|

Now, her busy workshop in Mumbai's

Worli district turns out swatches, samples

and full production runs for these and other

top designers. "We start with pure ideas,"

she says, "playing back and forth with mood

prompts and word associations. Then I turn

them into a swatch, and I get feedback, then

into a full size sample, and get more feedback.

Only then do I go into production."

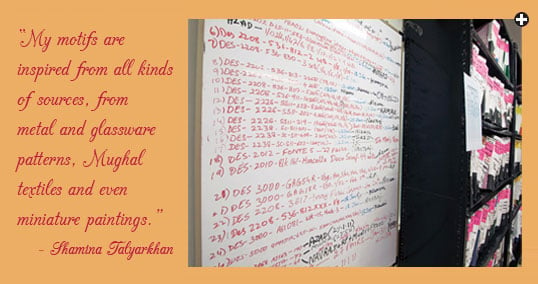

The order board hanging near the supervisors'

station lists current and upcoming

jobs by level of urgency. Today, all of them

seem to need to be finished and shipped

by tonight.

|

Her men embroider Mughal-style elements

onto panels of western fabrics like

tulle, georgette and chiffon, which are then

re-sewn into garments ranging from ball

gowns and wedding dresses to fancy sweaters

and casual jackets. At first, it seems

strange to see fine Indian stitchery combined

with suede, or crushed and coiled crepe, or

tiger-stripe-printed silk, pleated and covered

with peekaboo black netting. But then

it all makes perfect fashion sense: Just as in

Akbar's time, it is an amalgam of diverse

tastes and traditions.

"My motifs are inspired by all kinds of

sources," says Shamina, as she points to

her library of pattern books and museum

catalogues, "from bidri, or inlaid metal, and

glassware patterns, Mughal textiles in the

V&A's collection, even miniature paintings.

But I had to educate my workers too about

quality control. My fabrics are mostly pale

greens and pinks, lavenders and peach tones,

and their hands were often soiled from long

bus commutes. Luckily, soap flakes usually

did the job. My biggest problem was

the apprentices' reluctance to use thimbles.

Blood dripping from pricked fingers just

doesn't wash out!"

The process of arranging an embroidery

frame is almost as complicated as setting

up a loom. Cloth must be stretched

tight to be embroidered, but Shamina's fabrics

are usually too delicate to be stretched

and embroidered directly; they must first

be stitched flat onto a stronger nylon-mesh

backing. The backing is then stretched over

the frame by a cord with multiple loops.

The desired patterns are then pounced

onto the stretched fabric using chalk powder

and paper templates perforated with pinholes.

Four to six men can work comfortably

around one frame, sometimes working

on a single large pattern, more frequently working

on multiple smaller pieces to be cut out

and sewn individually onto sleeves, backs and bodices.

The needle must be pushed firmly through both the

base fabric and the nylon-mesh backing.

When the job is complete, the mesh threads are

unraveled and pulled away one by one, leaving the

fine fabric free with the embroidery work intact.

|

|

|

Haze silhouettes skyscrapers in Mumbai, top; in New York,

above, a shipment of embroidery awaits unpacking at Shameeza Embroideries,

where other finished dresses, below, await their clients. |

Twenty-six-year-old Muhammad Khalid

from Bihar is working on a painstaking

four-handed job with his bench-mate

Tasleem Muhammad, shaping and holding

down the pleats of a flower design to

be sewn tightly in place. If it is not done

right and consistently, the quality controllers

who inspect each piece will send it back

to be redone. Muhammad and Tasleem are

part of a larger production team responsible

for a six-week job: 270 pieces of four panels

each, later to be cut out of the fabric and

tailored individually into each dress.

At another frame, ari workers are fixing

five different kinds of blue beads as

well as square and round sequins onto the

fabric. A needleman picks up each shape

in a repeated sequence, sometimes stacking

two of the same shape at a single position

in order to add a third dimension to the

design. To save time and motion, an expert

might pick up multiple beads onto his needle,

which he can drop one by one into each

chain stitch without having to pick them

up individually. A needleman's eyes are the

first thing to deteriorate in this work—not

backs or legs as in Mumbai's unskilled

trades—and threading a needle is easy in

comparison to stitching tiny beads into a

perfect line with zero tolerance for disorder.

|

Shamina's best workers, she says, are her

swatch makers, because it is the swatches

that are scrutinized back in the New York or

Paris design studios before approval for full

production. Even so, swatches sometimes

go through several versions, sent back and

forth to Mumbai with cryptic comments

handwritten on the order card, like something

on a doctor's prescription pad: "Only

1 and 3 dot rows, no 4 dots," or "Add space

between floating fade out beads," or "Fewer

sequins per dot," and on and on.

When jobs back up in Shamina's workshop,

she sends them out to her subcontractor,

Muhammad Muazzam Siddiqui, one of

Mumbai's many start-up embroidery entrepreneurs

who are satisfying the demand

for handmade pieces, which has exploded

thanks to Internet-based marketing and

sales. Any Web site selling low-end Indian

garments offers much the same kind of ari

and zardozi stitchery, but the difference is

not only that the maal is plastic and glass

rather than gold and crystal, but also—and

critically—that the detail, the quality control

and the overall coverage of the cloth

is far less than what Shamina, Abu and

Sandeep produce.

Among Siddiqui's 40 employees, all

clustered around 15 embroidery frames,

is 22-year-old Mustaqim Shaikh, from

Mednapur village in West Bengal. Shaikh

started as an apprentice near his home

after finishing fourth grade and, ever since

coming to Mumbai six years ago, has felt

that he made the right decision. Looking

over at his boss, he says he sees himself

wearing those shoes in the not-so-distant

future. After all, he explains, in a prospering

country that adds hundreds of thousands

of cars to its roads every month, it is

only natural that more people than ever are

buying the most finely embroidered kurtas

and kurtis, saris and dupattas.

|

Louis Werner (wernerworks@msn.com)

is a writer and filmmaker living in New York City.

|

|

David H. Wells (www.davidhwells.com)

is a freelance documentary photographer

affiliated with Aurora Photos.

He specializes in intercultural

communications and the use of light and

shadow to enhance visual narrative, and has

twice won Fulbright fellowships for work in

India. His photography regularly appears in

leading magazines. A frequent teacher of

photography, he publishes The Wells Point

at www.thewellspoint.com. |