e are standing in the heart of the Latin Quarter of Paris. Famous landmarks, such as Nôtre Dame Cathedral, the

Luxembourg Gardens, the Cluny Museum, the Panthéon and the Sorbonne are within blocks. Yet hidden in full view

around us is another Paris that is often forgotten in the bustle: historic Arab Paris.

e are standing in the heart of the Latin Quarter of Paris. Famous landmarks, such as Nôtre Dame Cathedral, the

Luxembourg Gardens, the Cluny Museum, the Panthéon and the Sorbonne are within blocks. Yet hidden in full view

around us is another Paris that is often forgotten in the bustle: historic Arab Paris.

For many, an Arab Paris may seem of more interest to journalists than historians. After all, it's only relatively

recently that hundreds of thousands of Parisians speak Arabic as their first or second language, and that couscous,

mezze and shwarma have become as common as coq au vin. So it's all too easy to overlook a history that began some

500 years ago, when France became the first Christian nation to establish a diplomatic alliance with the Ottoman

Empire, initiating a flow of diplomats, intellectuals, tourists and students from the Eastern Mediterranean and

North Africa to the French capital.

"By the end of the 18th century, relationships with the Muslim world were so common as to have become banal.

People walked about Paris not even blinking when they saw someone wearing a turban, because they were so used to

it," says Ian Coller, history professor and author of the 2011 book Arab France. Turbaned figures were simply part

of the crowd in engravings, watercolors and oil paintings of the period—even in Jacques-Louis David's

early-19th-century "Coronation of Napoleon," where the Ottoman ambassador can be spotted among the dignitaries.

|

|

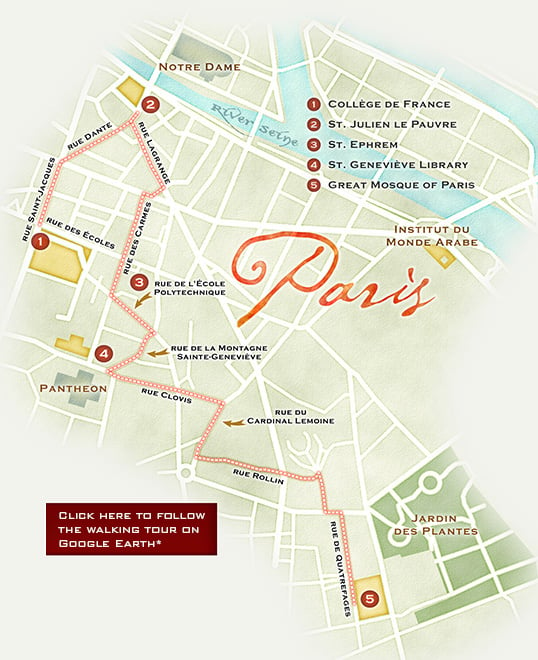

*This link requires that you have Google Earth installed on your computer. If you wish to install it now, go the

free installation site here. Tour producer: Ryan Petrie. |

When the Institut du Monde Arabe (ima, or Arab World Institute), a cultural partnership between France and 22 Arab

countries, launched its 2½-hour walking tour of Arab historic sites in Latin Quarter six years ago, its primary goal

was to educate the public by exploring France's historical links to the Arab world. "Now our mission is also to help

first- and second-generation French citizens to find and understand the roots of their grandparents' language and

civilization," explains Mona Khazindar, ima director general. Many participants

come on school field trips, and the

public tours are on Saturday afternoons from May to October, €16.70 ($21) a head. Individual visits can also be arranged.

On the spring Saturday when we set out to explore historic Arab Paris, we meet our guide under a tree by the iron gate

of the Collège de France, the Royal College until the French Revolution. François i

established the institution in 1530

to encourage independent thinking and break old modes of academic inquiry. An art collector, he also nudged France into

the Renaissance by bringing Leonardo da Vinci to Paris and, with him, the "Mona Lisa."

|

|

|

|

The ima begins its tour at the gate of the 482-year-old Collège de France,

where Arabic texts were among its first

library acquisitions and the Arabic language was first taught to Europeans. |

"The Collège was established as an alternative to the Sorbonne," explains our guide Anne Vincent, speaking in French.

"The king wanted to free scholars from controls on their research by both church and state and to allow students to

study without paying fees." It was at the Collège, she tells us, that Guillaume Postel introduced the first Arabic-language

courses in Europe. In the following centuries, the Collège would become the cornerstone for the study of Oriental languages

in France, and it would attract innovative scholars: Jean-François Champollion, who unlocked the Rosetta Stone's hieroglyphics,

was among them.

|

Until François i, Europe still viewed the Levant as a Crusader battlefield,

but François looked to the east primarily for

commercial and strategic partners. Ignoring criticism from his fellow monarchs, he was the first to exchange ambassadors

with the Ottoman Empire, which then stretched across North Africa to the Arabian Peninsula and north into Hungary. In 1536,

he and Suleyman the Magnificent established an alliance that would last nearly three centuries. About the same time, France

and Morocco also exchanged ambassadors.

In advance of the agreement with the sultan, Hayreddin Barbarossa, the powerful Ottoman admiral and governor of Algiers,

dispatched a delegation to France in 1533. Bearing a lion and 100 Christian slaves as gifts for the king, a second delegation

arrived the following year to coordinate Franco-Ottoman offensives against the Holy Roman Empire and to accompany the new

French ambassador to Constantinople. With the ambassador traveled Postel, the Arabic linguist who is sometimes called France's

first Orientalist. The king sent him along as an interpreter, but also with the assignment of bringing back Arabic manuscripts,

particularly scientific texts, to enrich the royal library. Among Postel's souvenirs was a thesis on Arab astronomy that is

still part of the French National Library collection.

|

|

Second stop on the tour is St. Julien le Pauvre, a 13th-century church whose current Melkite congregation claims roots

among Christian Arabs who followed Napoleon back from Egypt to France.

|

Before moving on from the Collège de France, Vincent nimbly fast-forwards to the 19th century by introducing us to

Jean-François Champollion, whose 1822 translation of the Rosetta Stone, found by Napoleon's troops in Egypt, opened

millennia of Egyptian history and created the scholarly discipline of Egyptology. An archeologist by training, Vincent

warms to her tale: Champollion had studied Arabic and other Oriental languages at the Collège de France, where he was

later appointed chair of Egyptian history and archeology. Also the first curator of the Louvre's Egyptian antiquities

department, Champollion was part of what became a mania for things Egyptian. Winged lions, scarabs and other Egyptian

motifs appeared in fashion, furniture and funerary art, particularly at Père Lachaise Cemetery, where Champollion

himself is buried under an obelisk-shaped tombstone.

"The French were mad about the Orient," Vincent says. "There were sphinxes everywhere." Not to mention the Luxor

obelisk at the Place de la Concorde, a gift in 1829 from Muhammad Ali, the Egyptian ruler who established a school

in Paris where Egyptian youth could study military science, mechanics, medicine and other practical skills. (He also

presented Charles x with a giraffe, a creature that hadn't been seen in Europe for over 300 years; an estimated

one-eighth of Paris's entire population came to see "Zarafa" after she was installed in the zoo at Jardin des Plantes,

the city's botanical garden.)

These were heady times in Paris. When a Moroccan delegation arrived in the winter of 1845-1846, the local press was

abuzz. One journalist reported that "the envoy from Morocco has caught the imagination of Paris. Everything about

him recalls the court of the Moorish kings of Granada and the brilliant Abencerrages of whom he is a descendant."

Muhammad as-Saffar, a scholar traveling with the ambassador, chronicled their social whirl of dinners, concerts,

balls, theater and tours around town. They received so many invitations that "we only accepted invitations from the

royal entourage or men of state."

|

|

|

|

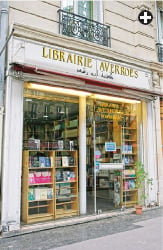

Along the way, the tour passes bookshops and cafés with long histories as gathering places for the Arab students

and writers who made the city an Arab capital. |

The glitter of that winter season was evident when as-Saffar described running into Egyptians, including two

grandsons of Muhammad Ali, at the king's New Year's party. "In all, there were about 60 people sent there by Muhammad

Ali to learn the sciences [that] one finds only there. These Muslims were not dressed like Christians, but wore long

gowns covered with so much gold embroidery, pearls and precious stones that the cloth beneath could hardly be seen.

Their buttons were studded with gems, and the girdles from which they hung their swords were heavy with gold. Their

splendor was indescribable."

But there was also a spiritual side to the Paris-Arab relationship. We dodge traffic as Vincent leads us down Rue

Saint-Jacques for our second stop: St. Julien le Pauvre, a tranquil spot on the banks of the Seine across from Notre

Dame. Outside this tiny church, which dates from the 13th century, a poster advertises classical music concerts.

The church is known for its superb acoustics, but we are here to learn about its historic Arab connection. At first,

it strikes us as strangely bare of the religious statuary so common in French churches, but Vincent explains that

we are not standing in a Roman Catholic church: St. Julien has been a Melkite (Byzantine rite) church since 1889.

Its congregation can trace its beginnings to Christian Arabs who were among the hundreds of refugees who followed

Napoleon back to France after his defeat in Egypt. She calls our attention to the iconostasis, the wall of icons and

religious paintings between us and the altar. Services, considerably lengthier than in the Roman tradition, are

conducted in Arabic.

|

|

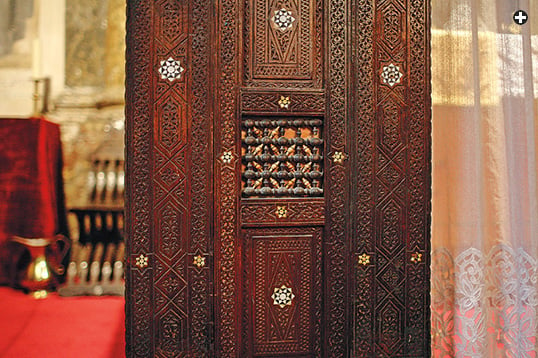

Fine woodwork reminiscent of the mashrabiyyah screens of Egypt and the Levant decorate the third stop on the tour,

St. Ephrem's Chapel, which since 1925 has offered rites in Aramaic and Arabic to France's Syrian Catholics. |

We take a break from history outside the church, although it is hard to escape history in the Latin Quarter. Vincent

points out that we are standing in the shade of a propped-up locust tree, reputedly planted in 1601, that is considered

the oldest tree in Paris. A German tourist asks Vincent who, today, is an "Arab" in France. How can North Africans be

called Arabs, he asks, if they are Berbers, and not, for example, from the Arabian Peninsula?

It's a familiar question for Vincent that touches the heart of the tour's educational mission. "It is defined by

language. An Arab is someone whose language is Arabic," Vincent begins. "There are 22 countries in the Arab world,

but not all are ethnically Arab." Most Arabs in Paris are from the Maghreb, the group of North African countries

from Libya westward. Mashriq is the term for Arabic-speaking countries east of Egypt and north of the Arabian Peninsula.

And Egypt is, well, Egypt. Because of France's long colonial history, the majority of Arabs in Paris hail from Algeria,

but when it comes to restaurants, she smiles, "the Lebanese are everywhere."

|

|

|

The tour ends at the Great Mosque of Paris, whose early 20th-century minaret, top reflects North African style,

using a light stone that blends into the city's streetscape. The gardens are open to the public, and it is a

popular site for weddings, above.

|

Paris has at times been described as an Arab capital, because so many Arab students, writers and artists came to

Paris as exiles in the early 20th century. "It was there and in Cairo that Arabic liberal thought had its early

footing," Fouad Ajami wrote in 1998 in The Dream Palace of the Arabs. Intoxicated by a spirit of liberty, in Paris

they founded Arabic magazines and newspapers, Arab bookshops and publishing houses. They gathered in coffee shops

to smoke shisha (waterpipes) and argue politics. Many were profoundly changed, like Tawfiq al-Hakim, who came from

Egypt in 1925 in a red tarboosh and went home five years later in a blue beret to write pioneering plays in Arabic.

"For the Orient, Paris has always been an intellectual capital. Beginning in the 20th century, generations of

students wanted to believe that the spirit could breathe on the banks of the Seine," observed Nicolas Beau, author

of Paris, Capitale Arabe.

Leaving St. Julien le Pauvre, we begin a hike up and over Mount St. Geneviève, the highest point in the Latin Quarter,

walking in the direction of the Oum Kalthoum Café and the Baghdad Café, where Arab students gather in the Latin Quarter

today. Halfway up the hill, we pause for breath on rue des Carmes in the stone courtyard of the Corinthian-style

St. Ephrem's Chapel, which since 1925 has been home to Syrian Catholics in France, with services in Aramaic and Arabic.

Like St. Julien le Pauvre, its superb acoustics make it a popular venue for concerts.

At the top of the hill is another reminder of the centuries-old ties the City of Light has with the Arab world:

Sainte Geneviève Library, named after the patron saint of Paris. Now part of the University of Paris, it may be the

city's oldest library, begun in a Benedictine abbey in the sixth century, when monasteries prized Arabic manuscripts

for their scientific and mathematical erudition. Reestablished as a scholarly library in the early 17th century, its

first librarian was Jean Fronteau, an expert in Middle Eastern languages.

Our final stop is the Great Mosque of Paris, an early-20th-century contribution to the cultural relations between

France and the Arabic-speaking Muslim world. It covers nearly a hectare (2½ acres), yet seems tucked away behind the

Jardin des Plantes. We are taken by surprise when we turn a corner and find ourselves in front of an Arabic bookstore

and a minaret soaring 33 meters (130') above a Moorish-style mosque.

|

|

The colorful walls of the mosque are ornamented using traditional patterns from Andalusian and Moorish zillij tilework. |

"When they built the mosque, they took elements from throughout the Arab world to create the ideal mosque. It has the

only minaret in Paris, but there is no call to prayer. That would be impossible in the Latin Quarter," Vincent says as

we enter the courtyard through a massive bronze-studded oak door to find ourselves in a kind of neo-Andalusia. Walled

with tile mosaic, the terrace is paved in white marble and filled with pools, fountains and flowers. Tourists can visit

the public spaces anytime, but the areas for prayers, sermons and the reading of the Qur'an are restricted to Muslims.

The largest mosque in France and third largest in Europe, the Great Mosque was inaugurated in 1926 by the president of

France with the bey of Tunis and the king of Morocco on hand. Built to serve the religious needs of French Muslims, it

honors the 100,000 Muslim colonial troops who died for France in World War i.

But in addition to being an important

religious center, the mosque is a highly popular enterprise among tourists and Parisians, Vincent points out.

You can eat lamb couscous or a tagine (Moroccan stew) in the mosque restaurant, nibble on baklava or smoke shisha under

fig trees in the patio, shop for North African souvenirs in the afternoon souk or even steam away your tensions in the

domed hammam, or traditional spa. It's no coincidence that our historical walkabout ends here, very much in the present.

We are ready for a plate of honey-soaked pastries and mint-infused black tea, which the waiters pour with a great flourish.

|

Nancy Beth Jackson, Ph.D., (nancybethjackson@gmail.com)

is a journalist and journalism educator who has lived in Paris, Cairo and Abu Dhabi. She is now based in Alton, Illinois,

a historic river town near St. Louis.

|

|

Isabelle Eshraghi (isaregards@hotmail.com) is a photojournalist

who covers news around the world from Paris. Born to a French mother and an Iranian father, she has won several awards for

her extended coverage of both women and men in the Middle East.

|