|

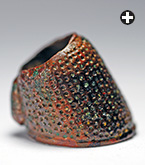

| The forerunner of the today’s thimble took the form of an open flat band rolled to fit around the finger. The earliest such thimbles, from China’s Han Dynasty (206 bce-202 ce), probably looked like this ring. Map: 1 |

'Tis like a helmet, nicked Where thrusting lances pricked; Some sword has dispossessed The helmet of its crest.

'Tis like a helmet, nicked Where thrusting lances pricked; Some sword has dispossessed The helmet of its crest.

Thus the 12th-century Andalusian poet Abu al-'Abbas Ahmad ibn Sayyid al-Ishbili vividly describes the thimble. In al-Ishbili’s time, the thimble—in several guises—was a familiar object from China to Spain and was probably just entering Europe with Crusaders returning from the Levant. A simple device designed to protect the finger or thumb from a needle-pushing injury, the implement by then had already undergone a remarkable evolution.

My wife and I were familiar with the thimble’s history when I started working at a referral hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, in 1990, and we were eager to learn about thimble-making in the kingdom. For example, we knew that ornate thimble-and-ring combinations had been crafted in silver and gold by nomadic peoples in Turkmenistan beginning in the 1700’s, and we wondered whether the nomads of the Arabian Peninsula had a similar tradition. I thought my patients, who came from different tribes around the kingdom, would be good sources of information about old thimbles and good sources of actual old thimbles, too. As it turned out, I was mistaken—but more about that later.

|

|

|

|

| Far Left: This thimble from Turkey is similar to Han-type thimble rings discovered in Tashkurgan, China, near the border with Pakistan, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan. Map: 2 Above: Three thimbles from Afghanistan highlight the appliance’s evolution. The open-topped, cast-bronze thimble at the far left is related to the Chinese thimble ring and probably dates to around the 10th century. The center thimble, also cast-bronze, but of a slightly later date, has a closed top and three crescents around the rim. The third thimble resembles the previous one, but the crescents extend to the top, where there

is a small knob. Map: 3 |

The earliest known thimble—in the form of a simple ring—dates back to China’s Han Dynasty (206 bce-202 ce). In the second century bce, when cultures in Europe, India and the Middle East were developing wrought iron, Han metalsmiths were producing hardened steel—an alloy of carbon and iron—through a process they called “a hundred refinings.” This involved repeated forgings of cast iron and allowed the fabrication of very fine, sharp, strong needles, critical for sewing Chinese silk. For most efficient use, these needles required a light metal pusher.

Earlier needles of copper, bronze, iron and gold could not withstand strong pressure: They bent easily and were no use for fine work. Edwin F. Holmes notes in A History of Thimbles (1985) that, although a flax-based textile industry was well developed in Egypt’s Middle Kingdom some 4000 years ago, no sewing activity or sewing implement is reflected in any tomb paintings. Actual examples of ancient thimbles “are conspicuous by their absence,” he says, possibly because thimbles of that time may have been made of leather, and leather disintegrates unless it is specially preserved.

|

|

| A Saudi tailor uses a brass sewing ring (inset) and a tension hook attached by a loop to his right big toe to sew at the annual Heritage Festival at Janadriyah, near Riyadh. Map: 4 |

As the Han expanded into Central Asia around the beginning of the first century bce, trade routes for such commodities as silk opened in the northwest of the empire; these connected to existing routes across Central Asia and the Middle East that led to cities like Damascus and Antioch and ports on the Mediterranean Sea. From there, goods were shipped farther west to Constantinople and Rome. Needles followed silks and thimbles followed the needles, though their westward diffusion was probably delayed by a Han Dynasty ban on the export of iron products.

The Han thimble ring, or zen-huan, was a flat band rolled into a cylinder without a seam. Archeologists excavating a Scythian settlement in the northern Black Sea city of Chersonesus turned up an open-topped metal thimble at a level dating to the second century bce—similar in date to a Han tomb sewing ring. The Chersonesus thimble is likely of kindred design to the Han thimble and illustrates how quickly technology can travel.

Han sewing rings have also been found in Tashkurgan, a Silk Road city in western China near the border with Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan. They are similar to cast-bronze thimbles found in excavations of Byzantine-era sites in Antioch and Corinth dating to between the ninth and 12th century.

Oddly enough, neither the Romans nor the Greeks before them appear to have used metal thimbles. It may be that leather or cloth finger guards proved sufficiently robust for their purposes. There are so-called Roman thimbles in museum collections, but the provenance of those metal thimbles is in fact not certain, and many have been removed from display. No well-documented archeological data link metal thimbles to any Roman site.

There is thus a gap of hundreds of years between the development of the thimble in China and its common appearance along the Silk Roads. Fine steel needles were rare and expensive, and—in addition to the Han ban on exports—it may simply be that not many people needed to use a metal thimble.

What is certain is that closed-top “thimbles began to appear around the eastern Mediterranean and also in Moorish Spain… from around the 10th century,” Holmes writes in Thimbles (1976). He goes on to cite regulations recorded by the 14th-century Egyptian administrator Ibn al-Ukhuwwa that strictly governed the craft of needle-making. For example, mixing steel needles with those made of “soft iron” was strictly forbidden.

It is also clear that, as the thimble moved west, its general shape changed.

The Silk Roads wound through Afghanistan and cast-bronze thimbles found there highlight this evolution. An open-topped thimble that derived from the sewing rings of China probably dates to the 10th century. Another thimble, manufactured a little later, has a closed top and three crescents around the rim. A third, perhaps a development from the second, features three rimmed crescents extending to its top, where there is a small knob. It is similar to thimbles excavated by a Danish expedition at Hama, Syria, before World War II and dated to between the 12th and the 15th century.

|

|

|

| Clockwise from left: “Turko-Slavic” thimbles were cast in bronze or iron and dimpled by hand. They often had ventilation holes and a six-pointed star at the top and were sometimes grooved around the rim. They are found farther north than “Abbasid-Levantine” thimbles (bottom right) and as far west as Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary. Map: 5 Bottom right: These thimbles, featuring chevron motifs separated by three hand-dimpled panels, were found in Hama, Syria, by a Danish expedition before World War II. Known as “Abbasid-Levantine” thimbles, they were likely made during the Abbasid Caliphate (656-1248) and taken to Europe by returning Crusaders. Map: 6 |

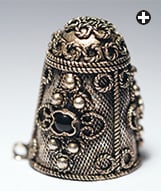

Most of these thimbles date to the time of the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad (750-1258), the “golden age” of Islamic science and culture. John J. von Hoelle, author of Thimble Collector’s Encyclopedia (1986), classifies them as “Abbasid-Levantine” thimbles—the rarest of three types manufactured in Islamic lands. They often have ledged rims and domed tops and are found on the eastern Mediterranean littoral. Von Hoelle suggests that Crusaders returning from the region introduced this type of thimble to pre-Renaissance Europe and that western European thimble makers adopted the style, which can still be seen in thimbles today.

|

|

|

| These Persian thimbles date to the 19th century. The 22-carat gold-and-enamel betrothal thimble portrays the bride on one side and the groom on the other, and the steel-topped silver-enamel thimble depicts bird scenes. They are rare and expensive and were undoubtedly crafted for the aristocracy. Map: 7 Far right: This fine gold-filigree thimble with a silver top is thought to have been made in Persia in the 18th century. The gold wire used to decorate the thimble is much finer than the twisted wires seen in early English filigree thimbles. The Persian filigree was applied to a gold base for stability. Map: 7 |

Thimbles of the northern Silk Roads were more bulbous and heavier than the Abbasid-Levantine variety. Called “Turko-Slavic” thimbles, they often carry a six-pointed star on their domes and may be grooved around the rim. They date from the 12th or 13th century and have been found as far west as Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary. The expansion of the Ottoman Turks into Europe, beginning in the 14th century, probably played a role in their distribution.

|

|

| These heavy, pointed thimbles, found in southern Spain, are known as “Hispano-Moresque.” Usually cast in bronze, they date from the 10th to the 15th century. Map: 8 |

To the south, thimbles journeyed through North Africa to Spain with Arab armies. These heavy work implements have pointed tops and are found mainly in Spain. Called “Hispano-Moresque” thimbles, they were probably used for sail making and stitching leather. No lighter thimbles have been discovered alongside them, indicating that there was no need for fine steel needles. Any personal sewing at the time may have been done using leather or cloth finger guards.

Hispano-Moresque thimbles date from the 10th to 15th century and are the type referred to by the poet al-Ishbili. Although most were cast in bronze, they have also been found in silver and gold, and they often carry a decorative band that may bear an Arabic inscription.

As Muslim artisans arrived in Spain, so did the art of inlaying gold or silver into darkly oxidized steel. It took its name from craftsmanship made famous in Damascus, particularly in the production and decoration of swords. The technique may have been used on thimbles as well, but I have not seen gold-inlaid thimbles dating from earlier than the 20th century. Notably, those thimbles are made in Germany and are sent to Toledo for band decoration, and many of the gold-inlay patterns are Islamic in style.

Thimble production was well established in France by the 13th century, perhaps stimulated by the arrival of thimbles (and steel needles) with returning Crusaders. Thimble production began in Nuremberg, Germany, the center of a well-organized brass-casting industry, in the late 14th century. There, free tradesmen turned cast blanks on a lathe and then either drilled or hammered indentations into them.

From Nuremberg, large numbers of thimbles were shipped on donkey-back to Venice for export all over the world. Nuremberg thimbles have been found in several excavated sites in Syria: Local thimble production during this time waned in the Muslim world.

The more delicate shapes of the European thimbles were embraced in Persia in the 18th century. During the Qajar dynasty (1794-1925), enamelwork on precious metals was one of the significant art forms of Isfahan. Qajar thimbles carry figurative scenes of birds and flowers and portraits of youth and couples, the latter type called betrothal thimbles.

|

|

| Silver niello thimbles made by artisans in the Marsh Arab area of southern Iraq often depicted life on the banks of the Tigris River. They featured camels, sailboats, reed boats with upturned prows, rush houses, palm trees and mosques and were sometimes signed by the maker. Map: 9 |

|

| This engraved silver Turkoman thimble with a gilded design is attached to a crown-shaped silver and gilded ring set with carnelian and turquoise stones. Turkoman thimbles date to the mid-18th century. Map: 10 |

Other forms of thimble adornment developed to meet foreign demand. In Ottoman times, the town of Amara, in the Marsh Arab area of today’s Iraq, was known for its silver workers and their niello decoration. Niello is a black mixture of copper, lead and silver sulfides that is used to fill in designs engraved or etched in silver or another metal, then fired, to increase the contrast and prominence of the design.

|

| This silver Turkoman thimble has an applied filigree border and rim, with gilded patterns. It is attached to a silver-filigree and gilded ring set with a 2.8-centimeter (1.1”) carnelian stone. Map: 10 |

Amara silver workers made mostly jewelry and domestic items prior to World War I, but during the war the town became a key base for the British military and the site of the chief military hospital in the region. Many soldiers visited the local suqs, and niello thimbles were among the souvenirs local artisans made for the Europeans.

The nomadic tribes of Turkmenistan and Afghanistan have been making highly decorated two-part silver and gold thimbles at least since the mid-18th century. Other examples of such thimbles, from Afghanistan date to the 13th century. Turkoman thimbles are often part of elaborate gold-and-turquoise bridal hand decorations. Many thimbles are attached to decorated finger rings, and most are made of silver with applied gold decoration.

When my wife and I began searching for thimbles in Saudi Arabia, I began by asking my trainees whether they knew the word for “thimble,” but—despite using drawings and hand gestures—I drew a blank. Then I asked a few patients, with the help of the young surgeons, but again I made no progress.

|

|

| Top: These two silver applied-filigree thimbles from Afghanistan, one with turquoise stones, date to the early 20th century. Map: 3 Bottom: These two rather crudely made modern Turkish thimbles are inset with glass stones. Each has a ring for attaching a chain. Map: 2 |

Finally a nurse volunteered the Arabic word for “thimble,” kustuban, and became the main translator and communicator in my search for “old” thimbles. Over the following months, it became apparent that Saudis who sewed did so without the help of a thimble. With the exception of the Hijaz, the western part of Arabia where there had long been extensive contact with pilgrims from around the world, there was very little western influence in the Arabian Peninsula before the discovery of oil in the late 1930’s, and it was thus unlikely that people had been exposed to western sewing tools.

Yemeni silversmiths sometimes traveled in the Peninsula with nomads, and I wondered if they had ever made thimbles. Searching antique shops, my wife and I found rings of all types, but no thimbles, and nothing like the thimble-and-ring combinations of Turkmenistan.

Toward the end of our stay in Saudi Arabia in 2001, the new National Museum opened in Riyadh. Among the exhibits were pre-Islamic artifacts dating back thousands of years, among them gold and steel needles, but again nothing resembling a thimble. In the more recent collection, dating back 70 to 90 years, there were thick leather finger covers from the Eastern Province—but we found that these were used by pearl divers to protect themselves from coral scrapes or sea-urchin spines, not for sewing.

We often passed through suqs where men sat cross-legged, sewing leather sandals or bishts, but we never saw any kind of thimble. It may be that tailors used fabric finger protectors—I had seen a picture of that—but we never witnessed it.

|

|

| Left: This brass “advertising” thimble was probably manufactured in France in the 1920’s. Its Arabic inscription translates, “Wrinkle-free natural silk textiles.” Map: 11 Right: Enamel flowers decorate

this contemporary gilded-silver thimble from Turkey. Map: 2 |

|

|

|

| These modern souvenir thimbles come (from left) from Jordan, Oman and Indonesia. They have domed tops, possibly a reminder of their Abbasid-Levantine ancestry. Map: 13, 14, 15 |

One notable thimble was on display at the annual National Heritage Festival at Janadriyah, near Riyadh, where my wife and I watched an old man sewing a quilt. He wore a dimpled gold ring, which he used to push his needle, maintaining tension in the material by means of a hook attached to his right big toe by a cotton band.

|

| This 20th-century steel thimble was made in Germany and sent to Toledo in Spain for damascene decoration. The steel has been oxidized and a gold pattern has been inlaid in an Islamic design around the border. Map: 12, 8 |

We hadn’t seen anything like this before, so I was surprised when a patient brought me a similar ring-and-hook device that had belonged to her grandmother. Then an old Bedouin lady attending my clinic passed me a parcel containing two ring-type thimbles that she said were very old. They were the first signs we had seen of thimbles used by the tribes and may have dated back about 100 years. Both looked as if they had been fashioned from the silver decorations on the barrels of old rifles.

Today, probably as a consequence of increased tourist activity and the influx of foreign workers, souvenir thimbles are available throughout the Middle East. In Turkey, production of inexpensive “European-type” metal thimbles, as well as more expensive gold and silver ones, seems to be growing—mainly to meet demand by tourists from elsewhere in the Muslim world. Some of these thimbles are decorated with semiprecious stones, and most have domed tops, possibly a reminder of their origins.

The journey of the thimble has been long and winding. Moving from East to West by trade and conquest, the utilitarian thimble later found its route reversed as exports from Europe grew to meet demand in the Middle East. Without Muslim traders and contacts that continued through war and peace, thimble-making might never have reached France and Germany, and we might still be pushing needles with some alternative device today!

|

William Isbister, MD, a retired professor of surgery, and his wife, Magdalena, have been collecting and studying thimbles for some 25 years. They lived in Saudi Arabia from 1990 to 2001 and now reside in Moosbach, Germany.

|