|

| This portrait of Cailliaud was drawn by the famous portrait artist André Dutertre soon after Cailliaud’s first return from Egypt in 1818. Cailliaud was 31 years old. |

|

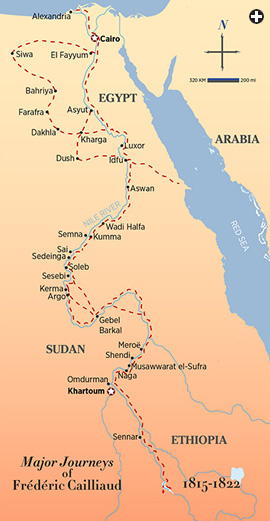

hen he returned to his native France in 1822, a hero’s welcome awaited Frédéric Cailliaud. Over the preceding seven years, his accomplishments as an explorer and scientist in Egypt had won him admiration both among his fellow scholars and in the popular press. He had rediscovered Roman-era emerald mines. He had braved intrigue, rebellion and the elements to become one of the first Europeans to explore both the Eastern and Western Deserts. His crowning discovery, on the heels of an Egyptian invasion of Sudan, had come when he ventured south to the present-day border of Sudan and Ethiopia and rediscovered Meroë, the capital city of the ancient kingdom of Kush. In addition, Cailliaud compiled the most important collection of archeological and ethnographic artifacts to reach France in the century between Napoleon’s invasion in 1798 and Auguste Mariette’s excavations in Saqqara in the late 1800’s.

hen he returned to his native France in 1822, a hero’s welcome awaited Frédéric Cailliaud. Over the preceding seven years, his accomplishments as an explorer and scientist in Egypt had won him admiration both among his fellow scholars and in the popular press. He had rediscovered Roman-era emerald mines. He had braved intrigue, rebellion and the elements to become one of the first Europeans to explore both the Eastern and Western Deserts. His crowning discovery, on the heels of an Egyptian invasion of Sudan, had come when he ventured south to the present-day border of Sudan and Ethiopia and rediscovered Meroë, the capital city of the ancient kingdom of Kush. In addition, Cailliaud compiled the most important collection of archeological and ethnographic artifacts to reach France in the century between Napoleon’s invasion in 1798 and Auguste Mariette’s excavations in Saqqara in the late 1800’s.

Shortly after his return, he published Travels in the Oasis of Thebes, with never-before-seen information on the people and places of the Western Desert. His Travels to Meroë (mer-oh-ay) not only offered similarly pioneering information on the peoples and regions south of the Nile’s first cataract, but also constituted the first scientific survey of Sudanese monuments. In addition, he brought back a large corpus of correctly copied textual material that, along with objects in his newly acquired collection, helped the historian Jean-François Champollion decipher the hieroglyphic language of ancient Egypt. So esteemed were Cailliaud’s contributions to knowledge that in 1824 he was awarded the French Legion of Honor.

|

| Three sequential images demonstrate how Frédéric Cailliaud, a former student of both drawing and jewelry design, produced the elegant color plates first published between 1831 and 1837. The version at far left is filled with his annotations of colors and details to be added; the center version is cleaner and more finely detailed, and the final version at right appeared as Plate 45a in Research on the Arts and Crafts of the Ancient Egyptians, Nubians and Ethiopians. |

Cailliaud’s origins, however, were humble. He was born in 1787, the third child of a master locksmith and municipal councilor in the Atlantic port city of Nantes. Shying from his father’s calling but showing aptitude for intricate detail, Cailliaud trained as a jeweler. To help him in this endeavor, he also studied drawing—a skill that would serve him well years later in Egypt. He left Nantes for Paris in 1809 to work as a jeweler, and he added  studies in mineralogy and natural history to his résumé. Two years later, he embarked on travels in Europe and the Mediterranean in order to complete his training and to start a personal collection of mineral specimens.

studies in mineralogy and natural history to his résumé. Two years later, he embarked on travels in Europe and the Mediterranean in order to complete his training and to start a personal collection of mineral specimens.

While in Greece, Cailliaud made a contact that led to brief work in Istanbul for the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud ii, for whom he enriched the sword sheaths of foreign guests with precious stones. From there, he set his sights on Egypt, which held great allure for scholars and explorers in the early 1800’s. Napoleon’s failed invasion had nonetheless opened the country to scientific opportunities, spurred on by such publications as the hugely popular Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt, an account of Napoleon’s invasion by his confidant, Dominique Vivant Denon, and the first volume of the encyclopedic Description de l’Égypte, which contained the first systematic and scientific survey of Pharaonic monuments.

|

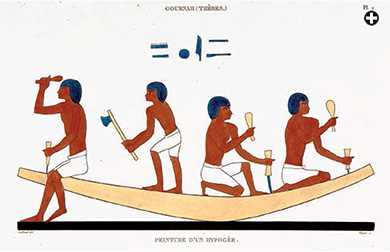

| Selecting from among a multitude of tomb paintings, Cailliaud often showed an eye for practical aspects of daily life, such as these four boat-builders, together with their tools, above, which he copied from the tomb of Ibi in Luxor and published as Plate 2 in Arts and Crafts. He followed it with Plate 3, below, which comes from bas-reliefs in the tomb of Paheri, in El-Kab. It depicts four boats in almost technical detail. |

|

Cailliaud arrived in Egypt in 1815. He quickly fell in with France’s vice-consul, Bernardino Drovetti, who brought Cailliaud on his first journey south along the Nile to Wadi Halfa, close to the second cataract and today’s Egyptian-Sudanese border. Drovetti also helped Cailliaud secure a post as mineralogist to Muhammad Ali, Ottoman viceroy and ruler of Egypt, who was keen to develop Egypt’s economy, industry and military. Cailliaud’s assignment was to rediscover emerald mines in the Eastern Desert, which had been depleted and abandoned by the Romans, with an eye to using more modern methods to extract gemstones and profit the viceroy. This official task also gave him the opportunity to undertake personal missions of exploration. He traveled first to Luxor to search for antiquities, which he acquired in abundance despite the limitations of his personal finances. It was also during these trips that Cailliaud began to record in his notebooks artwork and texts he found, most of them in tomb scenes in the Theban necropolis.

After charting the locations of potential emerald mines and their possible yields, Cailliaud struck out west of the Nile to the little-known oasis of Kharga, again in search of Pharaonic antiquities. In doing so, he became the first modern European to record the first-century-ce Roman temple of Dush. After a brief survey of the oasis, he decided to return to France to present his drawings and records.

|

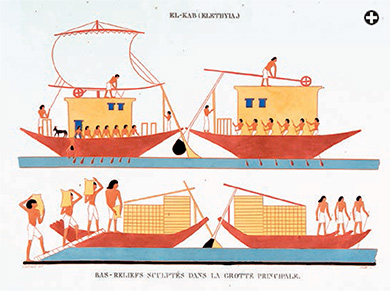

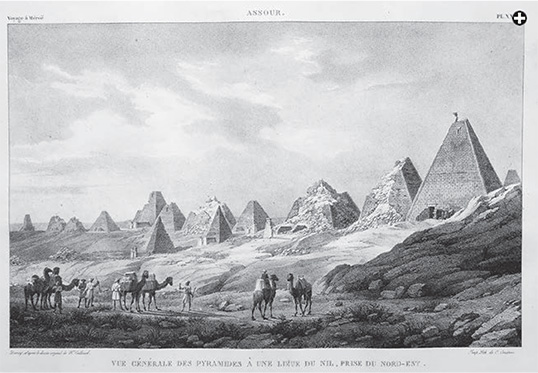

| Plate 36 in the first volume of Travels to Meroë included this lithograph that Cailliaud designed to show a general view of the site’s steep-sided pyramids. |

Upon his arrival in Paris in November 1818, word of his accomplishments spread quickly among the scientific elite. Edmé Jomard, who had accompanied Napoleon into Egypt 20 years earlier, was then editor of the Description de l’Égypte project. Jomard took a liking to the young Cailliaud and led him to greater opportunities. The government commission responsible for the Description recognized that Cailliaud could continue what Napoleon’s scholars had begun. Upon the commission’s recommendation, the French government bought both Cailliaud’s drawings and his artifacts, which were allocated to Paris’s Royal Library, and Jomard set about publishing the notes. In addition, the government formally charged Cailliaud to return to Egypt and visit places missed by Napolean’s savants: the Western Desert’s five major oases and the lands of Nubia along the Nile to the south. He was given money, equipment and the cartographic assistance of a naval officer named Pierre-Constant Letorzec.

Cailliaud returned to Egypt in October 1819, and he quickly received permits from Muhammad Ali to explore and excavate. Shortly thereafter, he set out for the most distant of Egypt’s oases: Siwa, famous for its Greek oracle, which had played a role in legitimizing the conquests of Alexander the Great. This was bold, as Siwa’s distance from the Nile placed it well beyond the range of the viceroy’s protection. The Frenchmen forged through the desert, unmolested by local tribes that had been known to shun and even kill earlier European explorers. They arrived in Siwa, and they successfully studied its temple of Jupiter-Amun. Turning south to Bahriya, they went on to traverse, over three months, the oases of Farafra, Dakhla and Kharga, recording all they encountered.

|

Some of the illustrations in this article were published between 1831 and 1837 in Research on the Arts and Crafts of the Ancient Egyptians, Nubians and Ethiopians. Only 100 copies of this book were printed and, soon afterward, the building in which they were stored collapsed; only some 50 copies survived. The intended subsequent volume of text, which would explain the images in the initial volume, was never completed. That manuscript, with its own original artwork, passed to Cailliaud’s son, who also did not complete the project. The history of the manuscript’s ownership thereafter is unknown until 2002, when it was acquired by Sims Reed, a London book dealer. In 2005 it was purchased by the second author of this article.

It comprises some 1000 pages of handwritten French, a nearly complete set of some 80 plates of Cailliaud’s artwork and a collection of supporting material and personal sketches. It is all based on notes Cailliaud made during his travels, and the text underwent several revisions. Most of it is written in pencil, in standard-sized notebooks. Occasionally scrap paper from other tasks was reused. The first author of this article translated a large portion of the somewhat archaic French as part of his work at the American Research Center in Egypt, which plans to publish it, in both English and French, later this year. |

Near the end of their trek, in March 1820, in Kharga, Cailliaud learned of a military campaign being organized to secure for Egypt the rich resources of the Sudan—including minerals. It was to be led by Muhammad Ali’s third son, Ismail Pasha. Cailliaud received the viceroy’s permission to accompany the army, and he was charged with resuming his mineralogical duties by prospecting for gold once they got south of Khartoum. Finding all available transportation requisitioned for the army, Cailliaud bought his own boat and, with a few months to spare before the campaign, the two Frenchmen sailed south to Luxor, where they amassed a further collection of antiquities. There, in the West Bank’s necropolis, they built a small, mud-brick house to store their objects, roofing it with wood from a commonly available source: pieces of painted, Pharaonic sarcophagi.

|

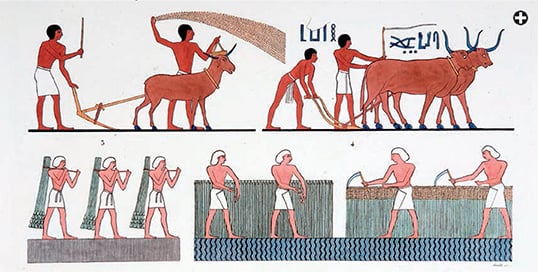

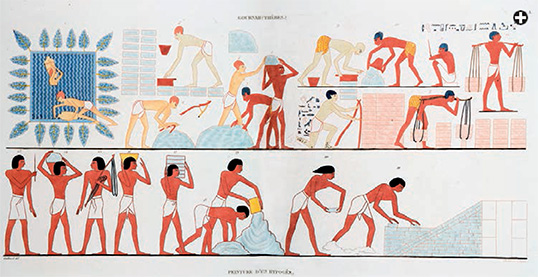

| In Arts and Crafts, Cailliaud often compiled artwork from several sites into themetic plates. Above: Sowing, plowing and harvesting papyrus, from tombs in Giza, Beni Hasan and Luxor. Below: Fig-harvesting (note baboons in the trees), granaries and plowing from the tombs of Amenemhat and Khnumhotep iii in Beni Hasan. |

The collection that Cailliaud amassed within this shelter was different from those of his contemporaries. He frequently chose items of little or no esthetic or market value, focusing instead on objects representative of everyday life in Pharaonic times: clothing, cosmetics, tools and complete funerary assemblages. No European to date had focused so intensely on these kinds of daily-life objects, and the resulting collection was of unique historical and ethnographic value. In addition, Cailliaud continued copying wall scenes in the Theban tombs.

In August, he and Letorzec traveled south to Aswan, where they joined the military expedition and were at once confronted with a nasty surprise: A conspiracy to discredit the authenticity of Cailliaud’s permission papers—and thus to remove him from the expedition—had been hatched by other Europeans attached to the mission. Their goal was clearly to remove a formidable competitor to their own quests for antiquities. Racing against the clock, Cailliaud had no choice but to return all the way to Cairo, have his documents confirmed and undertake the journey south to catch up to and rejoin the expedition.

In August, he and Letorzec traveled south to Aswan, where they joined the military expedition and were at once confronted with a nasty surprise: A conspiracy to discredit the authenticity of Cailliaud’s permission papers—and thus to remove him from the expedition—had been hatched by other Europeans attached to the mission. Their goal was clearly to remove a formidable competitor to their own quests for antiquities. Racing against the clock, Cailliaud had no choice but to return all the way to Cairo, have his documents confirmed and undertake the journey south to catch up to and rejoin the expedition.

Traveling by themselves proved unexpectedly advantageous. Cailliaud and Letorzec crossed from Aswan into the lands of Nubia, where they visited the monuments they found in their path. These included the enormous Pharaonic fortresses of Semna and Kumma; the islands of Saï and Argo; the temples of Sedeinga, Soleb, and Sesebi and the city of Kerma. Had they remained with the Egyptian army, they would likely not have had the time to study the monuments as carefully as they did.

They eventually met the Egyptian force at Gebel Barkal, which in the 15th century bce marked the southern limit of Pharaoh Tuthmosis iii’s realm. There, they were surprised to be welcomed by the European contingent, which to its own delight had just declared the ruins of Gebel Barkal to be none other than those of the famed and sought-after city of Meroë, known from classical sources as the capital of the kingdom of Kush. Cailliaud’s rivals were certain that their discovery promised them immediate fame.

|

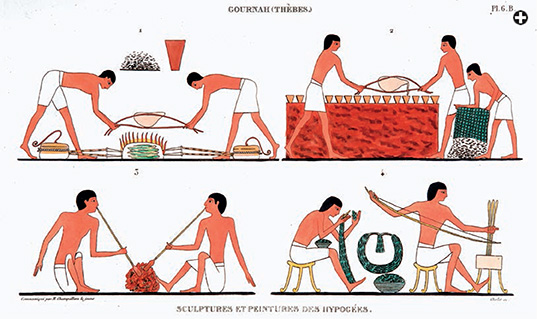

| Brickmaking, copied from the tomb of Rekhmire in Luxor. |

The army moved south again, and Cailliaud used his time to continue map-ping the unrecorded lands and peoples of Sudan. Cailliaud and Letorzec received permission to leave the army’s route to prospect for diamonds and gold near Shendi, on condition that they adopt Turkish dress, adopt aliases (Murad Effendi and Abdallah el Faqir) and be accompanied by an entourage. Not content to simply prospect for diamonds, Cailliaud ventured farther afield, lured by local stories of yet other great ruins. After a relatively short journey, the group spied tall, narrow pyramids rising from a necropolis. The location was close to the 18th parallel,  a fact that matched ancient sources’ description of the location of Meroë. Quickly, Cailliaud dismissed the idea that Gebel Barkal might be Meroë and proposed this site in its stead. His identification was ultimately validated, and the European discovery of the capital of Kush was credited to Cailliaud and Letorzec.

a fact that matched ancient sources’ description of the location of Meroë. Quickly, Cailliaud dismissed the idea that Gebel Barkal might be Meroë and proposed this site in its stead. His identification was ultimately validated, and the European discovery of the capital of Kush was credited to Cailliaud and Letorzec.

Excitedly, the Frenchmen surveyed the monuments and mapped the town and cemetery to record all they could as quickly as possible. Cailliaud’s elation at the discovery, however, was buried by the brutal realities of the invasion—ambushes, battles and executions of prisoners—upon rejoining the army at Shendi. When the expedition moved to Omdurman, opposite Khartoum, Cailliaud remained there for the next five months as the Egyptian army subjugated the region. He continued his ethnographic studies, and he created a French–Arabic lexicon of the names of the places he had visited.

Cailliaud’s prospecting for gold bore some results, but not enough to warrant large-scale mining. As a result, in the spring of 1822, Ismail Pasha decided that Cailliaud should return to Cairo, deliver what gold had been found and ask the viceroy’s permission for the army, too, to return to Egypt. The timing proved fortuitous: In October 1822, shortly after Cailliaud left, Ismail and his entourage held a banquet to celebrate their imminent return to Egypt. During the banquet, a former king of the area of Shendi named Nimir surrounded the Egyptian force and burned the invaders to death in their tents.

Cailliaud and Letorzec used their return journey to continue their explorations, including the palace-town of Naga, the temple of Musawwarat el-Sufra and returns to both Gebel Barkal and Meroë. The two crossed into Egypt in June and went directly to Luxor to recuperate, acquire still more antiquities and prepare for their return to France. Cailliaud once more threw himself into copying scenes from tombs on the West Bank and occasionally those from another burial site, El Kab.

|

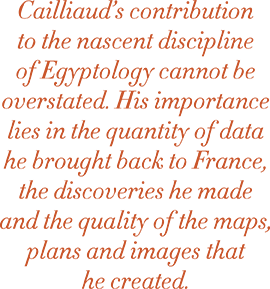

| Smelting of metal, blowing of glass and jewelry making, recorded from the tombs of Rekhmire in Luxor and Khety in Beni Hasan. |

It was during this period, too, that Cailliaud infamously crossed a line of archeological ethics. The tomb of Neferhotep had recently been rediscovered by a rival explorer working for the British. Cailliaud received permission to view and record the tomb’s lovely murals, but he used the opportunity to pry significant portions of a scene from its wall for shipment back to France. Caught in the act by a workman, Cailliaud was allegedly chased from the tomb, having plundered only a portion of the scene he sought. By the end of September 1822, the Frenchmen were back in Cairo, and to this day the purloined mural fragment resides in the Louvre. After a visit to the recently opened Step Pyramid of Djoser in Saqqara, during which they produced one of the first maps of its underground passages, they left for France on October 30.

|

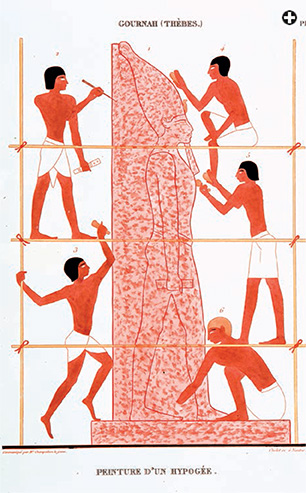

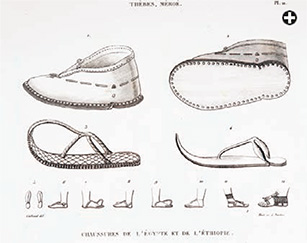

| Cailliaud’s interests ranged from far antiquity to his own immediate present. Above: Plate 15 from Arts and Crafts, from the tomb of Rekhmire, depicts sculptors using scaffolding and a variety of tools to outline, carve and polish a colossal statue, and Plate 21, below, which he did not color, is a compilation of visual notes on shoes he saw in his travels in Egypt and Nubia. |

|

Tales of daring and deceit aside, Cailliaud’s contribution to the nascent discipline of Egyptology cannot be overstated. His importance lies in the quantity of data he brought back to France, the discoveries he made and the quality of the maps, plans and images that he created. Edmé Jomard set to formatting Cailliaud’s Travels in the Oasis of Thebes as a reference work (much like the Description de l’Égypte); however, the publisher’s perfectionism long delayed publication, and, on publication of the first volume, the book was heavily criticized. It was regarded as an over-ambitious imitation of the now-famous Description. At the same time, the value of the first of two intended volumes—text and illustrations, respectively—was vastly decreased while the second remained forthcoming. Unfortunately, that second volume did not appear until 1862, just before Jomard’s death and when Cailliaud was 75. At that point, the work’s relevance was greatly diminished, as the objects in Cailliaud’s collection had been forgotten. In the meantime, recognizing the danger of lengthy publication delays, Cailliaud himself edited his second masterpiece, Travels to Meroë and the White Nile.

As Cailliaud’s reliance on Jomard diminished, his relationship with Champollion grew. Champollion and his brother, Jacques-Joseph, gave Cailliaud copies of the drawings of monuments they had created during their own Franco–Tuscan Expedition of 1828–1829. These images, along with a multitude of Cailliaud’s, formed the basis for what was supposed to be a third great publication, similarly divided into two volumes, one a visual account and the second one an explanatory narrative, titled Research on the Arts and Crafts of the Ancient Egyptians, Nubians, and Ethiopians. While the visual account was published in the 1830’s, Cailliaud died in 1869 before finishing the text.

His standing in the history of Egyptology had a similarly sad fate. His antiquities collections, quickly overshadowed by objects acquired by Europeans with more money, were broken up and dispersed to a number of museums instead of remaining intact where the entire collection might bear his name. Finally, Cailliaud turned his own attentions to the study of minerals and mollusk shells, two fields in which he also became a luminary, in addition to his Egyptian exploits. All of these factors conspired to relegate his name among Egyptologists from headline to footnote. With the forthcoming publication of his Arts and Crafts of the Ancient Egyptians, Nubians, and Ethiopians by the American Research Center in Egypt, we hope it will not always be so.

|

Andrew Bednarski (abednarski@arce.org) is an historian and Egyptologist who works for the American Research Center in Egypt. He is the editor and translator of Frédéric Cailliaud’s last great work on Egypt, the forthcoming Arts and Crafts of the Ancient Egyptians. The book, which is augmented by contributions from Philippe Mainterot, forms the basis for this article.

|

|

W. Benson Harer, Jr. is a retired physician and amateur Egyptologist. He has worked with the Brooklyn Museum Expedition to the Temple of Mut in South Karnak for 30 years. He also was an adjunct professor of Egyptian art at California State University San Bernardino. He has published extensively on medicine in Pharaonic Egypt. |