|

Written by Willem Floor and Jaap Otte

Photographs courtesy of the Montague Collection |

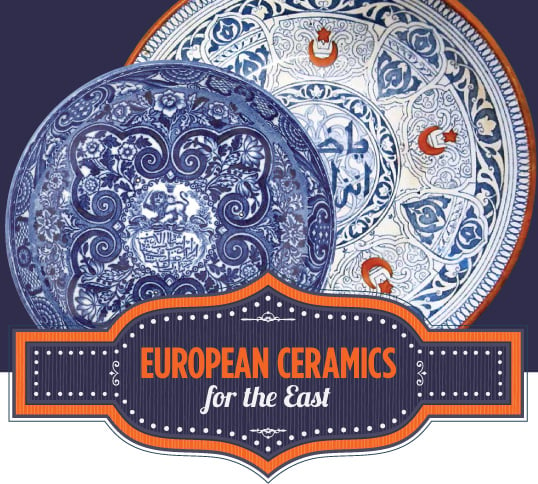

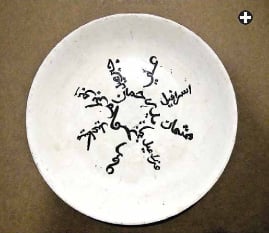

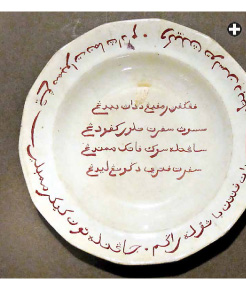

| Above left: Dish, Walker & Carter (uk), 1865–1889, 19 cm (7½") Ø, collected in Iran. The inscription and the lion and sun honor King Shihab al-Din of Iran. Above right: Plate, Creil et Montereau (France), 1884–1900, 21.5 cm (8½") Ø, collected in Tunisia. |

In 1972, Joel Montague was wandering through a market in Rabat, Morocco, looking for a birthday present for his daughter. He had in mind a piece of the traditional Moroccan ceramics he had often seen in the region. An American with a decade of experience in three Middle Eastern countries, Montague read Arabic and had become enamored of Islamic design and of the skill of the region’s craftsmen. He spotted a bowl on the shelf of a shop selling antiques and traditional crafts. It looked just right: clean, bright and decorated with traditional Islamic crescents and stars in abundance.

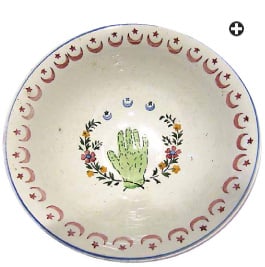

In 1972, Joel Montague was wandering through a market in Rabat, Morocco, looking for a birthday present for his daughter. He had in mind a piece of the traditional Moroccan ceramics he had often seen in the region. An American with a decade of experience in three Middle Eastern countries, Montague read Arabic and had become enamored of Islamic design and of the skill of the region’s craftsmen. He spotted a bowl on the shelf of a shop selling antiques and traditional crafts. It looked just right: clean, bright and decorated with traditional Islamic crescents and stars in abundance.

|

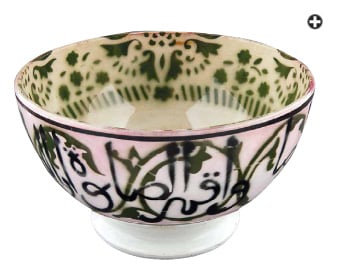

Bowl, Sarreguemines et Digoin (France), 1920–1940, 26 cm, 8.25 cm ↕ (10¼ by 3 ¼"). This bowl, which collector Joel Montague found in Morocco in 1972, began his interest in European pottery manufactured for export to Islamic lands.

|

And yet, something in the design seemed a little off: It was clearly Islamic, but unlike the other bowls on offer. To his surprise, the proprietor told Montague that the bowl was not Moroccan at all, but French. He added, somewhat testily, “The French sent their missionaries, then their soldiers, and then their ceramics!” Joel turned the bowl over and found the mark of a French manufacturer clearly visible on the bottom.

Thus began a 40-year passion: collecting ceramics made in Europe for export to Muslim nations. As Montague soon discovered, his lone Rabat pottery bowl was one of hundreds of thousands of ceramic pieces intended for daily use that had been exported by European potters to Muslim countries from around 1840 until the 1930’s. The exporters included some of the largest ceramics manufacturers in Europe, such as the still-famous Spode company of England, and their striking designs were customized for Islamic markets.

This simple, strong earthenware consisted mostly of cups, bowls, large dishes and plates. As export goods, they fetched good prices, and they displaced locally manufactured goods since they were generally more durable and their price was competitive. As this earthenware was mostly for everyday use, only a few samples of these once-common goods exist today, and their significance has been largely overlooked by craft and art historians.

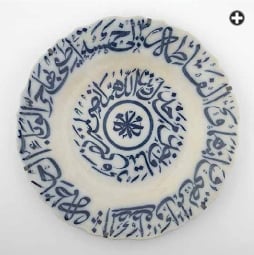

Dating from the first half of the 19th century, the first designs were imprinted on the ceramic body of the item using a technique called transfer printing, invented in England in the 18th century, that made it possible to decorate a large number of pots identically, even with complex designs.

|

| Above left: Dish, Walker & Carter (uk), 1865–1889, 19 cm (7½") Ø, collected in Iran. Above right: Plate, Creil et Montereau (France), 1884–1900, 21.5 cm (8½") Ø, collected in Tunisia. |

Printing images was much faster than painting by hand, although each step still required a great deal of manual labor. Working from drawings or prints on paper, an engraver would inscribe a design on a copper plate, which would then be covered with a thick and sticky ink. The plate’s surface was then wiped clean, leaving ink only in the engraved lines of the image. The plate was then printed onto treated paper, and the paper print was carefully pressed onto the surface of a pre-fired pot. (This last job was traditionally done by women and girls.) When the paper was removed, the image was left behind, and the printed decoration would be made permanent by firing the pot again.

Agents and business owners from the Middle East, North Africa and Southeast Asia all traveled to Europe to see the latest designs and place their orders. While ceramics with calligraphy in Arabic were sold to all Muslim countries, others were produced in Persian, Urdu and Basa Jawa—Javanese.

Decorations with Arabic texts were almost always printed in this way, eliminating the need for pottery decorators to actually write Arabic. Engravers often combined their carefully copied Arabic script with European decorative elements, creating eclectic designs that turned out to be popular with consumers in the Islamic world.

|

| Top row, left: Rice dish, Petrus Regout (Netherlands), 1890–1910, 26 cm (10¼"). The names of archangels surround those of the first four "rightly guided" caliphs of Islam. Top row, right: Plate, Sarreguemines et Digoin (France), 1920–1940, 22.8 cm (9"), collected in Morocco. Bottom row, left: Plate, Saint Armand (France), 1910–1940, collected in Tunisia. Bottom row, right: Rice dish, possibly Swinnertons (uk), 1906–1940, 37.5 cm (14¾"), collected in Sri Lanka. |

Also common were designs with images of a crescent moon and star; similarly, arab-esques and stars were popular in Malaysia and Indonesia, where they were known as bintang, which means “star” in both Malay and Bahasa Indonesia.

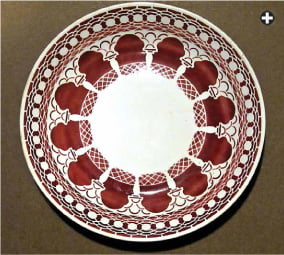

Whereas printing on ceramics was a specialized craft, hand-painting could be done by relatively untrained workers. Each painter used a large variety of brushes made from animal hair—generally camel, cow or ox—which was thought to be the best material because of its strength, springiness and ability to retain its shape. Hair brushes also hold a very fine point or edge. The decorations, mostly simple leaves and flowers, were hand-painted onto the unglazed earthenware in one or more bright colors. To enhance the design, workers sometimes used shape-cut sponges, sometimes grouping shapes next to one another; sponging the pot with different colors or types of paint also yielded distinctive and unusual patterns. These floral designs, though European in origin and style, also turned out to be popular in many parts of the Islamic world.

|

| Bowl, Nimy (Belgium), 1910–1930, 11.4 cm Ø, 8.9 cm ↕ (4½ by 3½"), collected in Tunisia. |

By the 1920’s, manufacturers began to decorate ceramic wares destined for Muslim countries using stencils and paint sprayed directly onto the object. This permitted a large variety of decorative images, such as the pillars of mosques, the Hand of Fatima, more half-moons and stars, and others.

England, where a huge ceramics industry had developed in the 18th century, was an important source of the earliest exports to the Islamic world, primarily between 1840 and 1880. English potteries had traditionally exported their wares to continental Europe and North America, but by about 1840 those markets had become saturated, and the middle classes increasingly preferred more fashionable porcelain over earthenware. English potteries looked elsewhere for customers, and expansion into the Islamic world roughly followed the path of colonization.

|

Copeland Spode, still known today for its tablewares, was one of the largest English manufacturers. The famous firm, founded by Josiah Spode in 1770, passed into the hands of the Copeland family in 1883. The earliest pattern designed for export to the Muslim world, with Jawi, a historic Malay script that used Arabic letters, was registered with the Patent Office in London in 1853. As with most manufacturers, not much is known about Copeland’s exports to the Islamic world beyond the remaining products themselves, which carry the distinctive Copeland factory mark.

rom 1860 onward, potteries in Scotland also started to export worldwide, particularly to Southeast Asia. Exporters included Methven, Cochran and others, but standing above all was the famous Glasgow Pottery, established in 1841 by brothers John and Matthew Bell and aimed squarely at the export market. Trade to Southeast Asia proved so successful that the Bells ordered a large number of printed designs adapted to local tastes with stylized dragons, mythical figures and geometric patterns. Plates often had the name of the decoration written in Arabic script under the Bell factory mark.

rom 1860 onward, potteries in Scotland also started to export worldwide, particularly to Southeast Asia. Exporters included Methven, Cochran and others, but standing above all was the famous Glasgow Pottery, established in 1841 by brothers John and Matthew Bell and aimed squarely at the export market. Trade to Southeast Asia proved so successful that the Bells ordered a large number of printed designs adapted to local tastes with stylized dragons, mythical figures and geometric patterns. Plates often had the name of the decoration written in Arabic script under the Bell factory mark.

|

| Left: Plate, Sacavém (Portugal) for J. S. Benchaya (Casablanca), 1920–1940, collected in Morocco. Right: Plate, Copeland Spode (uk), 1853–1970 (possibly 1870), 26 cm (10¼") Ø, collected in Indonesia. The Arabic inscription testifies to the oneness of God and Muhammad as God's prophet. |

Most of the ceramics exported to the Muslim world consisted of plates and large dishes, because many customers were accustomed to eating from a communal plate. Chinese manufacturers produced only bowls designed for eating with chopsticks, but those proved impractical for people who ate with their fingers. European soup plates, however, with their sloped rims, had the desired form.

|

| Lidded bowl, manufacturer unknown (France), 1910–1930, collected in Tunisia. |

Bell’s competition came from Dutch, German and French potteries that started making the same wares. One of the largest European ceramics factories was named after its founder, Petrus Regout, in Maastricht, The Netherlands. In 1836 Regout built a modern steam-powered pottery and was soon able to make ceramics that could compete with the best English products. From 1880, his exports took off worldwide. From order books and correspondence with agents and buyers in the firm’s extensive archives, we know Regout sold his wares in Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Sudan, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, Iran, British India and Indonesia. Regout made small coffee cups for Turkey and the Middle East, tea sets for Iran, and plates, bowls and large dishes that can still be found all over the Islamic world.

Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria, under French rule at the time, were supplied by large factories in France: Sarreguemines, Digoin, Saint-Amand, Gien and Creil et Montereau. The largest, the Sarreguemines pottery, also exported to other Muslim lands, mainly Turkey, Egypt and the Sudan, as well as the Dutch Indies. The large variety of wares, in particular café au lait cups for North Africa, display many different star and half-moon designs.

The first evidence of an attempt to create an export product that was not purely a European interpretation of Islamic design appeared on ceramic wares made in Portugal between about 1920 and 1940 for S. J. Benchaya, a Jewish businessman in Casablanca, Morocco. The products were unusual in that Benchaya sought to create designs influenced by both traditional Moroccan pottery and European Art Deco, and characterized by strong geometric elements. They were made exclusively for him at the Sacavém ceramics factory in Portugal.

|

| Above left: Plate, W. Adams & Sons (uk), 1840–1860, 26.7 cm (10½") Ø, collected in Sri Lanka. The pattern was called "Malay." Above right: Large dish, Saint Armand (France), 1910–1930, 30.5 cm (12") Ø, collected in France. The decoration depicts the Prophet's Mosque in Madinah, Saudi Arabia, and the Arabic city name indicates the dish was made for the Arabic-speaking market. |

Other potteries making wares for the Muslim world included the Nimy pottery in Belgium, the large potteries owned by members of the well-known Boch family in Belgium and Germany, and the Kuznetsov and Gardner potteries in Russia.

World War ii disrupted the ceramic export trade, and it never recovered. Colonies became independent and often did away with the privileged status that the European manufacturers had enjoyed, switching instead to lower-priced ceramic imports from countries like Japan and China, while others founded their own ceramics industries.

And what about the bowl Joel Montague bought more than 40 years ago in Rabat? It became the cornerstone of a collection now comprising well over 100 everyday ceramics made in Europe for Islamic markets, and which Joel collected from North Africa, the Middle East, Turkey, Iran, India and as far away as Southeast Asia. It is probably the only collection that shows the whole breadth of styles of these simple but enjoyable ceramics from all across the Islamic world.

|

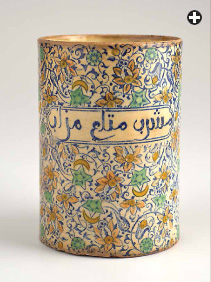

| Above left: Tankard, Gien (France), 1880–1910, 10.8 cm Ø, 15.9 cm ↕ (4¼ by 6¼"), collected in France, possibly intended for the Turkish market. The Arabic inscription reads "drinking cup of the shrine." Above right: Two café au lait bowls, Digoin (France), 1910–1930, 9.5 cm (3¾") Ø, collected in Morocco. |