|

| Pietro della Valle spent a dozen years, from 1614 to 1626, traveling in the East. His detailed letters from the journey, meant to inform his compatriots about little-known lands, were published in three volumes in 1650, 1658 and 1663. |

The Italian book-collector, linguist and avid correspondent Pietro della Valle is one of the most important, yet least known, Middle Eastern travelers of the 17th century. In spite of his very active contribution to western knowledge of the Islamic world and his romantic personal history, he has been relatively ignored, largely because there has never been a standard, easily available edition of his voluminous letters in either Italian or English.Tracing his travels from Turkey to Egypt, the Levant, Persia and the west coast of India, his writings run to more than a million words.

ella Valle’s great value lies in his lively, detailed descriptions and his ceaseless curiosity: He really was interested in everything. Where possible, he compared what he saw with earlier accounts, both classical and those of such travelers as the French naturalist Pierre Belon (1517–1564), as well as information gleaned from the Turkish, Persian and Arabic texts to which he had access.

ella Valle’s great value lies in his lively, detailed descriptions and his ceaseless curiosity: He really was interested in everything. Where possible, he compared what he saw with earlier accounts, both classical and those of such travelers as the French naturalist Pierre Belon (1517–1564), as well as information gleaned from the Turkish, Persian and Arabic texts to which he had access.

In addition to recording what he found, he exhibited a healthy skepticism about what he learned secondhand, noting, “I was told this, but have no way of establishing whether or not it is true,” or “I tried to find out more about this, but could find no one whose information seemed at all reliable.”

|

| Della Valle was thrilled by the Pyramids of Giza when he first saw them in 1615, and he spent a great deal of time and effort exploring the Great Pyramid himself. This engraving is from Les Six Voyages de Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, published in 1676, six decades after della Valle’s visit. |

He collected books, plants and information of all kinds and even took along an artist to record his travels. He wished to give his compatriots a clear idea of eastern lands, for both mercantile and diplomatic reasons, although his own interests were largely intellectual. Unfortunately, none of the numerous sketches and paintings he mentions has survived.

Della Valle was born in 1586 to a wealthy, aristocratic Roman family. In his mid-20’s, he joined a Spanish naval expedition against corsairs on the coast of North Africa. After that, disappointed in love, he moved to Naples where, depressed to the point of considering suicide, he was advised by his close friend and physician, Mario Schipano, to travel.

He determined, therefore, to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. To give his journey more point, della Valle planned to send back detailed letters to his friend, who would, he wrote, “extract a clear and well-composed account of my entire pilgrimage.” That, in fact, Schipano failed to do, but della Valle completed his part of the bargain—and much more. He returned home a dozen adventurous years after setting off, and il Pellegrino (“the pilgrim”), as he was often called, published one volume of his letters during his lifetime, while two more appeared posthumously.

Della Valle embarked for the Holy Land in June 1614, sailing from Venice to Constantinople (today’s Istanbul). In the Ottoman capital, he made a point of seeing not only monuments, but also events ranging from the bayram festivities marking the end of Ramadan, with features like swings and ‘ajalaat, an early version of the Ferris wheel, to the military parades that took place as Sultan Ahmad i and his troops marched out against Persia’s Shah Abbas i. Then, to gain a better understanding of what he would see on his travels, he stayed in Constantinople for a year, studying Turkish, Arabic and Persian and, for academic purposes, Hebrew.

“Much to my annoyance,” he reported in February 1615, “for more than two months my Turkish language teacher … has abandoned me, because he has been busy with his own affairs, but now he has returned to giving me lessons, at which I am delighted and am studying like a mad dog, and to good purpose.”

|

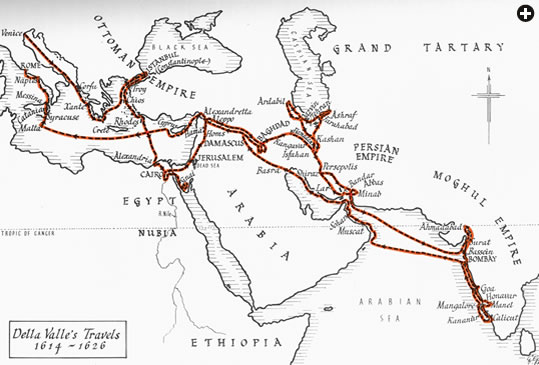

| Della Valle traveled several thousand kilometers, as shown in this 1953 map from William Blunt's Pietro's Pilgrimage: A Journey to India and Back at the Beginning of the Seventeenth Century. His first stop was in Constantinople (Istanbul), where he spent a year studying Turkish, Arabic, Persian and Hebrew. |

In Constantinople, della Valle also began trying to acquire texts, both for Schipano, a competent Arabic scholar, and for himself, ultimately building the core of a fine library.

He sailed to Alexandria, Egypt, in September 1615. In a letter from Cairo dated January 25, 1616, he described his sightseeing, remarking on the beauty of Mamluk architecture, especially the tombs at al-‘Arafa, the famous City of the Dead. Naturally, he visited the Pyramids, making an exhausting exploration of the inside passages of the Great Pyramid.

Della Valle was very keen to acquire an intact mummy to bring back to Italy. Examples were not easy to find, for they were often looted of their jewelry and then ground up, since the resulting powder, called mummia, was believed to have medicinal properties. Typically, he wanted to see exactly how mummies were excavated and even went down into the pit himself. His account of this activity is fascinating, as are his descriptions of the finds.

|

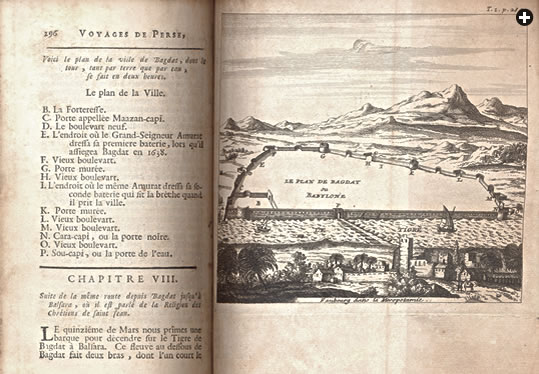

| Tavernier’s engraving of 17th-century Baghdad, alongside the Tigris River, may resemble what Pietro della Valle saw as he approached the city in 1616. It was here that della Valle met his “Babylonian love,” Ma‘ani, whom he married. |

It is again typical of della Valle that he paid attention to everyday life, as well as the great tourist sites. He noted that some houses had paintings and inscriptions on the walls indicating that the owner had been on the Hajj. Having a very Italian interest in clothes, he described not only the costume of the upper classes, but also the blue jellabas worn by peasants of both sexes—a very long, wide-sleeved robe, which sounds like the thobe still worn by certain settled Bedouin groups in the Bethlehem region—and the various ways of wrapping a turban.

Della Valle described his pilgrimage to Jerusalem, where he spent Easter and where, although very devout, he exhibits a certain skepticism about some of the celebrations. Then he traveled north to Damascus, where he was delighted to find several rare Samaritan manuscripts, including one with explanatory notes in Arabic. He wrote to Schipano from Aleppo to give him the good news and debated the best way to ensure that his collection was made available for its prime purpose: to spread knowledge.

From Syria, della Valle decided to journey to Persia via Baghdad, for he was very curious to meet Shah Abbas, who had been engaged in diplomatic discussions with European rulers about trade and about containing Ottoman imperial ambitions. With his usual energy, he explained how he had special cases built to transport his kitchen equipment easily by camel and protect the contents if dropped. In addition, he ordered special containers to “give the water a very pleasant smell and taste and even keep it cool.” Everything was to have a “most elegant” look. Finally, on September 16, 1616, he shaved his head, donned a turban and dressed himself and his retinue “in the Syrian manner so as not to be recognized” and departed.

|

| Della Valle and his entourage would have stayed in a khan like this during their travels from city to city. |

In Iraq, he gave a long description of the Bedouin way of life, noting that the women did not cover their faces. He was also fascinated by the Bedouins’ tattoos and apparently even got one himself—something exceedingly daring for a Roman gentleman at that date. Indeed, he liked to wear local dress, both for convenience and to experience different fashions. However, he was very annoyed when his fine Italian underwear was stolen, though relieved that the thieves had not gone for his books and papers.

Della Valle was much impressed by the desert guides. They “have a mental image of every place, the water sources, the various roads, both long and short,” he wrote. “At night they observe the stars, but by day they go by land marks, noting whether it goes up or down, the color, the kinds of plants that grow there and—and at this I really marvelled—the smell, so that they easily find whatever roads they wish.” All the more remarkable, the guides always led the caravan directly to wells when they were needed, even though they had no parapets and were completely invisible at a distance.

He traveled through the territory of the powerful and famous Amir Fayyad who, to della Valle’s surprise and pleasure, maintained such control of his domains that caravans could cross the desert in reasonable safety. Describing him and his lands, della Valle added: “… this Emir claims to be able to show his unbroken descent from Noah, something which I find hard to believe but, if true, would be a nobility possibly without equal in this world. Certainly, I am of the opinion that if any nation can boast of a true and ancient nobility of lineage over a long period of years, it is indeed that of the Arabs, in spite of the rough life they lead in the desert, firstly because they live free, which is a very important point—and this is the sole reason why they do not wish to be subjected to life in cities—and then also because since the beginning of the world they have never mixed with any other nation but always marry among themselves, not only among equals, but almost always with those of the same blood.”

|

| Isfahan was undergoing extensive reconstruction under the eye of Shah Abbas i when della Valle visited in 1617. He had long wished to see the city, but his greatest interest was in meeting Shah Abbas himself. |

As always when traveling, della Valle visited every archeological site he could. He described the ruins, for example, at “Isrijeh” and “al-Taijbeh” (Isriyah and al-Taybah) in the desert on the way from Aleppo to Baghdad, as well as what he believed to be the Tower of Babel. His tendency to compare places to sites in Italy that would have been familiar to Schipano and his potential readers may seem a little parochial, but in fact “larger than Piazza Navona” in Rome or “ruins higher than the tallest palace in Naples” give a useful order of magnitude for monuments that no longer exist.

At Ur and Ctesiphon, he noted that he picked up pieces of tile, brick and samples of bitumen—to the amusement of the locals, “who do not understand our taste for such curiosities.” He also pointed out that Baghdad was obviously not ancient Babylon, as was commonly believed, “for one can see clearly from … the architecture, the Arabic inscriptions in numerous places, carved or moulded in stucco … that this is modern construction and, without the slightest doubt, Muslim….” He added that he hoped his Arabic would soon be good enough to check what he has been told against the Arab histories.

|

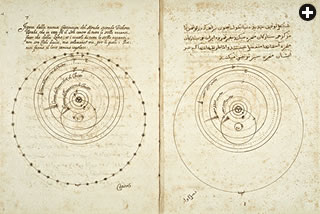

| Della Valle’s treatise on the heliocentric cosmology of Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, written in Italian and Persian, included Brahe’s model of the solar system. Della Valle wrote the paper in Goa for a scholar he had met in Lar, Persia. |

On della Valle’s arrival in Baghdad, disaster struck: One of his Italian servants killed the other in a stupid brawl over precedence, and della Valle described in detail the maneuvering necessary to prevent his entire household from being arrested. On the other hand, it was in Baghdad that perhaps the most important event of his life took place: He announced, quite out of the blue, that he was married to his “Babylonian love,” a girl named Ma‘ani—“an Arabic word meaning ‘significance’ or ‘intelligence’....”

The story was a romantic one. He had heard of Ma‘ani on the journey from Aleppo and decided that he had to meet her. A mutual acquaintance provided an introduction. Her parents welcomed him with the warmest hospitality, helping him establish himself and his suite in appropriate lodgings. Before she ever saw him, Ma‘ani dreamed of him, and at their first meeting she handed him a quince, a ritual wedding offering in Greece and across the Levant since classical times. On both sides, it was love at first sight.

“Although it is not well seen for husbands to exaggerate their wives’ beauty,” wrote della Valle, he could not resist describing Ma‘ani at length, even explaining how her eyes were elongated with kohl. He described her as of excellent family, Christian, born in Mardin, Turkey, her mother Armenian, and “Arabic is her native tongue, but she also speaks Turkish well, as she usually does with me, since I still only know a little Arabic….” He went on to say how much he appreciated her intelligence and high spirits—and fearlessness. Even when under attack by bandits, she preferred to stay and watch, guarding the men’s coats and bundles, rather than flee.

Della Valle wrote that Ma‘ani dressed in the Syrian manner—although she very much liked the idea of Italian fashion—and covered her head “as the Bedouin women do … a similar effect to the veils of our nuns, or Spanish widows….” He admitted that some things about her seemed a little barbarous, such as wearing a nose ring, and said he persuaded her to remove it, although her sisters refused.

Della Valle concluded this long missive, dated December 16 and 23, 1616 (many of his letters are in the form of a diary, written over several days or weeks), with the wish that Schipano should start editing his letters, because he hoped that before long they would be able to sit down together and put the finishing touches to them, since he planned to return shortly, as soon as he had visited Isfahan.

After Christmas, the young couple left for Iran. “I set about changing my clothes from Syrian to Persian,” della Valle wrote. He also found a country barber to shave off the beard he had cultivated during the previous 16 months. ”I wanted him to make me look completely Persian, in other words with cheek and chin shaved and with long moustaches…,”he noted. Ma‘ani was “heartbroken” when she saw him, and was only placated when he explained that when “traveling to different countries, it was necessary to adapt to different customs.”

Three months later, they were in Isfahan, the city that della Valle had so wanted to visit and which Shah Abbas was in the process of remodeling with the great mosques and monuments that can be seen today. He described the place and its inhabitants in detail; he was particularly struck by the great variety of people and their customs, especially the Indian community and the Christian quarter at New Julfa. This had been established by Shah Abbas for the Armenians whom he had forcibly deported from their country, largely in the hopes that they would stimulate the economy through manufacturing and trade. Della Valle described the terrible suffering they endured along the way, although conditions when they actually reached New Julfa were generally good.

|

| En route from Isfahan to Hormuz on the coast in 1621, della Valle stopped at Persepolis, copying and later publishing the first cuneiform inscriptions to be seen in Europe. He correctly deduced that the writing was read from left to right, but could not decipher it. |

At Isfahan, della Valle met a number of interesting people, including scholars of various nationalities. Among them was Muhammad Qasim ibn Hajji Muhammad Kashani, known as Susuri, who later sent him a copy of his encyclopedic dictionary, the Majma’ al-Furs Susuri, on its completion in 1626. Dedicated to Shah Abbas, this was a standard reference work for much of the 17th century. It must have been of particular interest to della Valle, who was working on his Turkish dictionary at the time. Unlike a number of his other projects, this was completed and prepared for the press, although it was never published. He was also interested in religion, and a copy of a letter to him from “Mir Muhammad el Vehabi [al-Wahhabi], a nobleman of Isfahan,” continuing their earlier discussion on religious topics, survives.

As Shah Abbas traveled about his kingdom, della Valle followed him. Their meetings and conversations shed a rare, unofficial light on being entertained by that monarch.

At Qazwin, in the winter of 1618, Shah Abbas met with foreign ambassadors, and della Valle set out to gather as much information as he could. He considered the Russians very uncouth, but he was fascinated by the menagerie brought as a gift by the Indian ambassador. The elderly Spanish ambassador, Don Garcia da Silva y Figueroa, also attended, and his diaries offer an interesting complement to della Valle’s account.

The gathering broke up and della Valle, though ill, managed to make his way back to Isfahan with Ma‘ani, arriving in December. There, they met some of her family, including her parents, who had come on a visit. For the first time, della Valle mentioned Mariuccia, a Georgian girl, about eight years old, orphaned at the time of the Persian conquest of Georgia, whom Ma‘ani had adopted, perhaps partly as consolation for not yet having a child.

In June 1619, there was another great conclave of ambassadors, and della Valle gave a vivid, often amusing, account of the festivities, including those organized for the ladies, of which Ma‘ani provided a full report. We learn, too, how in the evening the shah wandered about the town visiting coffeehouses and shops, including that of an Italian art dealer who sold, among other things, “portraits of the kind they sell for a crown at Piazza Navona..., but which here cost ten sequins and are considered cheap at the price.” A crown (coronato) was a Neapolitan silver coin and a sequin (a Venetian zechinno) was a gold coin weighing about 3.5 grams, so the markup was substantial.

Lingering in Isfahan, Della Valle covered innumerable topics, from serious to more frivolous: his growing taste for the local cuisine and how he will readapt to food at home; the different techniques for storing ice; and his plans to export Persian cats, of which he kept a great number, to Italy. His descriptions are scattered with Arabic and Persian words, especially technical terms and dialect expressions, meant for Schipano, but still of interest today.

One thing among many others is striking at this date: the efficiency of the mail system across the Islamic world. It is difficult to determine the exact number of della Valle’s letters to Schipano, given his habit of writing diary letters and sometimes beginning and ending sections with greetings, but it appears there were at least 36. Of his missives, only one is missing and that was lost by Schipano himself. Conversely, when della Valle complained that he had received letters from Venice, Sicily, France, Spain, Constantinople, Baghdad and India, but none from his friend, that was because Schipano had not written for more than two years, not because of a failure of the postal service.

Ma‘ani’s family wanted to return to Baghdad. Della Valle’s health was bad, affected by the bitter winter of 1620-1621, believed to have been the coldest since 1232, and his thoughts likewise turned to home. International politics, however, affected his plans. The war between Persia and Turkey meant the Aleppo route was blocked, so he and a number of other Europeans were effectively trapped. Furthermore, Persia had joined with the British to drive the Portuguese out of Hormuz at the southern end of the Arabian Gulf, making that route uncertain and dangerous. Nevertheless, they set out.

On the way, they stopped at Persepolis, which, as usual, della Valle described in detail, though not always accurately, for he was in an uncharacteristic hurry.

From Persepolis, they journeyed to Shiraz and then headed for the coast. They were in high spirits, for Ma‘ani at last was pregnant, when news came that hostilities had begun around Hormuz, where they were hoping to embark for Europe via India.

|

|

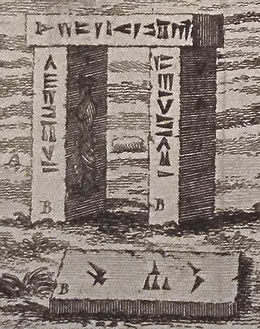

| Above: The coat of arms created for Ma‘ani della Valle, who died in Minab, near Hormuz, in 1621 at the age of 23, opens the memorial volume produced for her funeral in Rome in 1626. The inscription, in Syriac, reads “The servant / of God / Ma‘ani.” Top: Ma‘ani is portrayed in this edition of della Valle’s travels published in 1982 in Baghdad. |

They decided to wait at nearby Minab, where there was a group of English merchants, one of them an old friend of della Valle’s, and see what developed. The place, however, proved unhealthy. Mariuccia fell ill first, followed one by one by all the party, and on December 30 his beloved Ma‘ani died. She was 23 years old.

Della Valle hardly knew what to do next. He felt he could not bear to leave Ma‘ani in such a place and had her embalmed—something the local women were, surprisingly, competent to do—and sealed in a coffin to take with him for burial in Italy. Then, very ill himself, he and his entourage continued on their way. He said he remembered almost nothing of the journey until a month after Ma‘ani’s death, when he reached Lar, nearly 300 kilometers (180 mi) to the west, and collapsed. There, he slowly recovered under the care of an exceptionally competent doctor and in the companionship of his erudite friends. “Nowhere,” he wrote, “that I have been in Asia, in fact nowhere in the whole world, have I found as many learned men and distinguished scientists as at Lar.”

Some months later, della Valle found himself again at Shiraz and at last, in the winter of 1623-1624, he and 12-year-old Mariuccia set out for India. Della Valle’s letters are largely concerned with his experiences in Goa, but there are also some very interesting and unusual accounts of the smaller kingdoms to the south, between Goa and Calicut. Even there, he hunted for manuscripts and managed to add a palm-leaf book and the stylus used for engraving it to his collection, as well as an accurate description of the production process.

He did not have much opportunity to travel in the Mughal regions of India, and what he did tell added little to the much fuller accounts of other travelers. At Goa, however, he continued to correspond with his learned friends at Lar and Isfahan, and worked on various literary projects.

|

| The seal of Ma'ani della Valle, which appears in her multilingual memorial volume, repeats the Syriac wording on her coat of arms. |

On November 4, 1624, della Valle wrote his final letter to Schipano from India and on December 17 he set out for Basra via Muscat. After pausing at Naples to stay with Schipano, at last, on April 4, 1626, he arrived back in Rome. With his usual sense of drama, he wrote that he entered his house by the back door, “as is fitting for a widower.”

Della Valle lived out the rest of his life in Rome, engaged in a variety of intellectual and musical activities, and remained in correspondence with major oriental scholars, east and west. Signora Ma‘ani was buried in the Church of the Ara Coeli, and when Mariuccia—whom Ma‘ani had entrusted to della Valle on her deathbed—had reached a suitable age, he married her. They had 14 children.

The first volume of della Valle’s letters was published in 1650 and, after he died in 1652, four of his sons brought out the remaining two volumes in 1658 and 1663. They were quickly translated into French, German and Dutch, and partially into English, and came to be considered, as il Pellegrino had wished, a major source of information on the Muslim world.

|

Caroline Stone divides her time between Cambridge and Seville. Her latest book is The Curious and Amazing Adventures of Maria ter Meetelen: Twelve Years a Slave (1731–43), translated with Karen Johnson and published by Hardinge Simpole in 2011. |