|

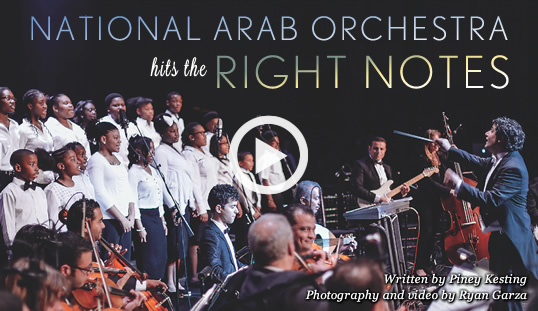

| Conductor and nao founder Michael Ibrahim, right, leads the orchestra and the chorus of Building Bridges through Music students on May 31 at the Detroit Music Hall, below, which opened in 1928 and is now the home venue for the nao. |

Sometimes, a song can change a life or, in this case, 20 lives. On May 31, at the historic Music Hall Center for the Performing Arts in downtown Detroit, Michigan, before a full house awaiting the annual concert of the National Arab Orchestra (nao), Music Director Michael Ibrahim stepped up to make an announcement. Last fall, he explained, the orchestra was awarded a grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation to start an after-school program called Building Bridges through Music. The purpose of the program, he added, is to teach Arab music in public schools that serve low-income neighborhoods.

Sometimes, a song can change a life or, in this case, 20 lives. On May 31, at the historic Music Hall Center for the Performing Arts in downtown Detroit, Michigan, before a full house awaiting the annual concert of the National Arab Orchestra (nao), Music Director Michael Ibrahim stepped up to make an announcement. Last fall, he explained, the orchestra was awarded a grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation to start an after-school program called Building Bridges through Music. The purpose of the program, he added, is to teach Arab music in public schools that serve low-income neighborhoods.

onight you will be hearing the product of this inaugural program with these fine young students from the Woodward Academy,” said Ibrahim as he turned to face his chorus: 20 fourth- to eighth-graders standing, self-consciously, on risers behind the musicians. Most had never performed on any stage, let alone sung with a professional orchestra. Ibrahim raised his baton, and the students burst into a spirited rendition of “Zuruni,” a classic ballad from Lebanon, which they sang entirely in Arabic. The audience erupted in applause and rose to give the students a standing ovation throughout their performance. For their second number, they sang Pharell Williams’s contemporary hit “Happy” using Ibrahim’s arrangement for Arab instruments as well as the students’ own hand and dance moves.

onight you will be hearing the product of this inaugural program with these fine young students from the Woodward Academy,” said Ibrahim as he turned to face his chorus: 20 fourth- to eighth-graders standing, self-consciously, on risers behind the musicians. Most had never performed on any stage, let alone sung with a professional orchestra. Ibrahim raised his baton, and the students burst into a spirited rendition of “Zuruni,” a classic ballad from Lebanon, which they sang entirely in Arabic. The audience erupted in applause and rose to give the students a standing ovation throughout their performance. For their second number, they sang Pharell Williams’s contemporary hit “Happy” using Ibrahim’s arrangement for Arab instruments as well as the students’ own hand and dance moves.

“I was about to cry when they sang,” recalls Sachi Yoshimoto, a Los Angeles-based violinist who has played with the nao since 2012. “Their performance was an inspiration and touched everyone in the audience as well as in the orchestra.” Noting her own Japanese heritage, she adds that “witnessing African-American school kids skillfully and joyfully sing ‘Zuruni’ made me proud of studying Arabic music and of keeping the heritage alive as a non-Arab musician. This type of cross-cultural exchange is precisely the reason why I joined the orchestra.”

Percussionist Sam Parsons believes that the dynamic performance “was one of those experiences that define people.” A jazz musician by trade, he has performed with the nao since 2011, when he was an undergraduate at the University of Michigan. “When the Woodward Academy students walked on stage, it rekindled the exact same electrifying feeling I had the first few times I played with the orchestra,” he says. “They were amazing.”

|

| “It was my goal from the beginning to have a full-time professional orchestra and to also build a school for Arabic music,” says Ibrahim, below. Among three singers on the nao’s May 31 program was Aboud Agha, above, who first performed as a teenager in Syria. |

The stories behind both Building Bridges through Music and the nao itself begin with Michael Ibrahim. A Syrian-American, born and raised in Sterling Heights, Michigan, Ibrahim, 30, began studying the ‘ud, or Arab lute, at age 10, and he soon discovered a passion for classical Arab music. In 2009, while a student at Eastern Michigan University, he formed his first ensemble, a takht, or traditional Arab chamber group, of seven student musicians playing the ’ud, violin, qanun, riqq and nay (Arab zither, tambourine and reed flute, respectively). That same year, he started the Michigan Arab Orchestra, which by 2011 comprised not only the takht, but also an Arab community choir he had founded. Victor Ghannam, a well-known Arab-American musician who often composes music for television, played with Ibrahim from day one. “It went straight to my heart,” says Ghannam. “What’s better than preserving our heritage?”

The stories behind both Building Bridges through Music and the nao itself begin with Michael Ibrahim. A Syrian-American, born and raised in Sterling Heights, Michigan, Ibrahim, 30, began studying the ‘ud, or Arab lute, at age 10, and he soon discovered a passion for classical Arab music. In 2009, while a student at Eastern Michigan University, he formed his first ensemble, a takht, or traditional Arab chamber group, of seven student musicians playing the ’ud, violin, qanun, riqq and nay (Arab zither, tambourine and reed flute, respectively). That same year, he started the Michigan Arab Orchestra, which by 2011 comprised not only the takht, but also an Arab community choir he had founded. Victor Ghannam, a well-known Arab-American musician who often composes music for television, played with Ibrahim from day one. “It went straight to my heart,” says Ghannam. “What’s better than preserving our heritage?”

In January, the orchestra renamed itself the National Arab Orchestra to reflect both its focus on education and its national presence. On January 24, it held its premier performance under the new name in the Atlanta Symphony Hall in Georgia. Violinist Katie van Dusen regards the new name as “a better reflection of our current identity, because musicians come from all around the country and sometimes the world to join us.”

One of them, Austin, Texas-based composer and violinist Roberto Riggio, says the orchestra gives him the opportunity to grow as a practitioner of Arab music while at the same time “it’s also great to see that the nao is making an intentional effort to step forward and declare cultural exchange an explicit purpose.”

“When I first started this orchestra five years ago, it was my goal from the beginning to have a full-time professional orchestra and to also build a school for Arabic music,” explains Ibrahim. “We don’t have that, we need it and we can sustain it. If the Arab arts and our culture are going to be saved,” he adds, “it will be done here”—meaning in the us. “We need to preserve this music and bring it alive again.” As an accomplished musician himself, and with a rising reputation as an innovative musical director, it’s been easy for Ibrahim to attract skilled, diverse and passionate musicians; however, he admits it was harder to hit the right notes when it came to building and funding an educational program. “Musicians are usually not good business people,” he confesses.

|

| “It’s great to see that the nao is making an intentional effort to declare cultural exchange an explicit purpose,” says violinist and composer Roberto Riggio, who travels from Austin, Texas, to play with the nao. |

Enter Moose Scheib, a young 34-year-old Lebanese-American entrepreneur based in nearby Dearborn. A graduate of Columbia University Law School, Scheib founded Mizna Entertainment, which in 2007 produced the first Arab-American comedy shows in Michigan. Aged seven when his family immigrated in the late 1980s, Scheib didn’t listen to much classical Arab music until he sat down at his first Michigan Arab Orchestra concert. Then, he says, he fell in love with it.

|

| “I like connecting people. I’m a bridge-builder by nature,” says Moose Scheib, who led the incorporation of the nao. “Music is an important way to connect.” |

“I like connecting people. I’m a bridge-builder by nature,” emphasizes Scheib. “Music is an important way to connect. If I’m going to work on something and put my talents to use, I want it to be something I can pass on not only to my daughter, but also to other kids and generations to come,” he adds.

Leaving the music to Ibrahim, Scheib set about legally incorporating the orchestra, expanding its board of directors and finding it a home. Given that Greater Detroit has one of the largest and most diverse Arab-American communities in the country, Scheib turned for advice to Vince Paul, president and artistic director of the Detroit Music Hall. But instead of giving advice, Paul simply invited the nao to become his resident orchestra.

“I wanted this to be the people’s theater,” says Paul, who became Detroit Music Hall director in 2006. Given the extraordinary diversity of the city, he adds, “I wanted people to think that of course the Hall would have a resident Arab orchestra.” The orchestra’s educational aspirations made it a natural fit with Paul’s own philosophy as well as an ally in his desire to alleviate the scarcity of music programs of any kind in Detroit’s public schools.

According to Scheib, some 70 percent of Detroit’s urban-core schools lack music educators. “The fact that kids can’t be exposed to music in a city known as the home of Motown is just terrible!” he exclaims. “The arts are an integral part of being human and connecting with others, especially when you don’t speak their language.“ Early last year, Ibrahim, Scheib and nao board member James Cline began to brainstorm about starting an Arab music after-school program, and later in the year, based on a proposal led by violinist van Dusen, the nao received a Knight Arts Challenge grant for $100,000. “The Building Bridges through Music program is where we start,” says Ibrahim. “It’s like laying that first cornerstone.”

When Woodward Academy’s after-school program director, Marsae Mitchell, heard about Building Bridges through Music, she was eager for her school to be its first host. Woodward, she explains, is a “Title i” school, meaning that all of its students come from families living at or below the official poverty level. Funding for after-school programs is scarce to non-existent.

|

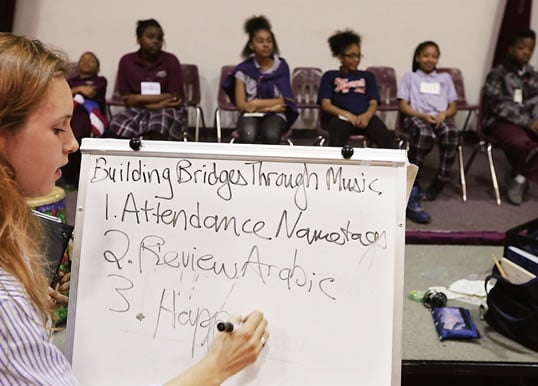

| In early May, with their performance weeks away, NAO double bassist Maggie Hasspacher writes out an afternoon’s agenda. |

“I love to see the children having an opportunity to experience another culture, especially knowing that a lot of them don’t even have a chance to leave their side of town in Detroit,” comments Mitchell, whose own degree is in the performing arts. “To see them learn a different language and learn about different music instruments is awesome.”

She notes that even in diverse Detroit, most of her students had never met anyone of Arab heritage. She chuckles when recalling that one of the first questions the kids asked Ibrahim was whether or not he ate at Burger King, and their surprise when he replied that yes, he did.

|

| Ibrahim accompanies rehearsal of the Arabic ballad “Zuruni”. |

Starting in October with 20 students from fourth to eighth grade, selected from among Woodward’s student body of 700, the program met weekly in classes taught by Ibrahim using a curriculum designed by nao double bassist Maggie Hasspacher. It was difficult at first, says Mitchell, who also assisted in the classes and supervised an additional weekly practice. “The students weren’t enthusiastic about singing in a language that they didn’t understand, or being exposed to a culture they weren’t used to,” she says. Some of the parents, too, were anxious, uncertain about the value of the program.

According to Hasspacher, Ibrahim, too, needed time to adjust. “He had never taught in an inner-city school, and he had no clue what he was getting into,” she notes with a laugh, adding that he had never taught children before. Ibrahim agrees. “They didn’t know how to sing, let alone speak another language, let alone know anyone outside their own circle,” he says. In January, Hasspacher began to lend support by co-teaching, and she and Ibrahim put together a curriculum that integrated Arab and western music for a two-way cultural exchange.

|

| Khalil Cross picks up an end-of-class high-five from Ibrahim. |

Every week, the students practiced the Arabic lyrics to “Zuruni,” learned a few basic Arabic words and were taught how to recognize some musical notes. Ibrahim introduced them to the ’ud, the qanun and the nay; he exposed them to his own background and culture. By mid-May, the students knew all the words. They were ready.

Cheyenne Williams and Jaya Pullen, both in seventh grade, say they enjoyed the class and that they would do it again if they could. Cheyenne says she plans to major in music education in college, and she liked being able to sing every week. “It was really interesting to sing in a new language, and it makes me want to learn more about the Arab language and the culture,” she adds.

|

| Woodward’s director of after-school programs, Marsae Mitchell, helps lead dance practice for “Happy.” |

“There is something about music that breaks down barriers,” observes Woodward Academy superintendent William Jackson, who praises the program that “exceeded my expectations.” Arts, he says, “bring in the right-brain element. Instead of putting our kids to sleep, let’s expose them to things that liven them up, like music and dance.” Indeed, as the night of the performance came near, the school’s survey of test scores for the Building Bridges through Music students showed overall improvement in their math and reading grades.

“There is something about music that breaks down barriers,” observes Woodward Academy superintendent William Jackson, who praises the program that “exceeded my expectations.” Arts, he says, “bring in the right-brain element. Instead of putting our kids to sleep, let’s expose them to things that liven them up, like music and dance.” Indeed, as the night of the performance came near, the school’s survey of test scores for the Building Bridges through Music students showed overall improvement in their math and reading grades.

On the night of the concert, Jackson, Mitchell and many other Woodward teachers, staff and parents attended. “The kids really made me proud,” exclaims Mitchell. “Not only was the concert excellent, but they sang beautifully, and they were wonderful representatives for Woodward Academy.” What pleases her as much as their performance is the shift in their attitudes. “At the beginning of the program, they were not at all interested in singing in Arabic,” she recalls, “and now they are talking about wanting to come back and sing again.”

“I loved the sense of accomplishment and joy I saw in the kids as they performed,” comments van Dusen. “I was sitting in my chair on stage wishing everyone could understand how cool it is that we have a choir full of African-American kids performing with an Arab orchestra for this audience in downtown Detroit. Here is an authentic and meaningful portrait of Detroit and its musical culture presented in a way that facilitates relationships across cultural boundaries.”

|

| “It was really interesting to sing in a new language, and it makes me want to learn more about the Arab language and the culture,” says seventh-grader Cheyenne Williams. |

“The program was a huge success, and it opened up a fraction of the world to [the students],” says Ibrahim. “In the beginning, they started off kicking and screaming,” he recalls. They thought Arabic “was weird because it was a different culture and something they hadn’t experienced before. Once they performed in the concert, all of them wanted to do it again. They loved it, and they really felt good about themselves after being up onstage.”

The students weren’t the only ones feeling good. Reflecting on his own youth, Ibrahim says he “had a lot of people telling me ‘you can’t, you won’t, you shouldn’t.’ The philosophy that helped me get out of my rut is what I tried to teach the kids every week. I told them, I started off just like you, and I’m the proof that you can do anything you want as long as you are willing to work hard for it.” And that, he believes, would be the best note any of them could hit.

|

Piney Kesting (pmkhandly@hotmail.com) is a Boston-based freelance writer and consultant who specializes in the Middle East. She is currently working on a book about women entrepreneurs in the Middle East, Pakistan and Turkey. |

|

Ryan Garza (ryan@popmodphoto.com) is a staff photographer for the Detroit Free Press and the 2013 Michigan Press Photographer of the Year. |