|

| robert french / bridgeman images |

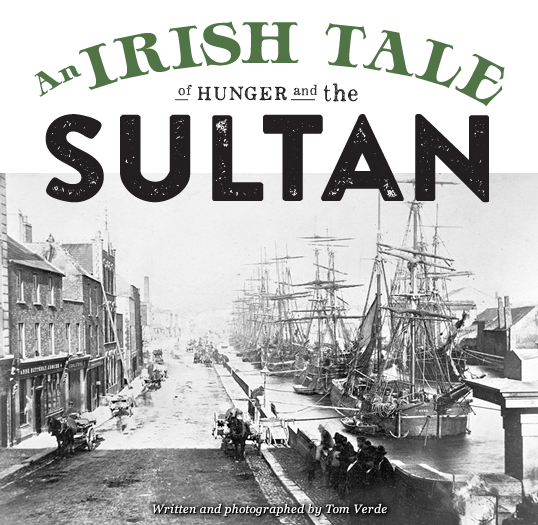

| Since the late 12th century, Drogheda, Ireland, has thrived on maritime commerce. This photo of the Boyne River docks was made in 1885, a generation after “The Great Hunger” of 1847 that lasted into the early 1850s: If indeed three Turkish ships brought food aid during that time, it is likely they would have tied up here. |

he story goes like this: In 1847, the worst year of the Irish potato famine, an Irish physician in service to the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul beseeched the sovereign to send aid to his starving countrymen. His pleas moved Sultan Abdülmedjid i to pledge £10,000 sterling; however, upon learning that England’s Queen Victoria was sending a mere £2,000, the Sultan, out of diplomatic politesse, reduced his donation to £1,000. Nevertheless determined to give more, he secretly dispatched three ships loaded with grain to call at the port of Drogheda in County Louth, north of Dublin. In gratitude, the city of Drogheda incorporated the Turkish star and crescent into its municipal crest, a symbol that endures to this day, appearing even on the jerseys of the Drogheda United football club.

he story goes like this: In 1847, the worst year of the Irish potato famine, an Irish physician in service to the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul beseeched the sovereign to send aid to his starving countrymen. His pleas moved Sultan Abdülmedjid i to pledge £10,000 sterling; however, upon learning that England’s Queen Victoria was sending a mere £2,000, the Sultan, out of diplomatic politesse, reduced his donation to £1,000. Nevertheless determined to give more, he secretly dispatched three ships loaded with grain to call at the port of Drogheda in County Louth, north of Dublin. In gratitude, the city of Drogheda incorporated the Turkish star and crescent into its municipal crest, a symbol that endures to this day, appearing even on the jerseys of the Drogheda United football club.

Now, like many an Irish tale, some of the story is true and some is legend, while other parts? Blarney.

|

| Dedicated in 1997 in Dublin to honor the millions of Irish who variously endured, emigrated or perished, “Famine,” by sculptor Rowan Gillespie, is a graphic reminder of the nation’s most desperate years. |

Like many other foreign governments, the Ottoman court indeed sent famine aid to Ireland in 1847. And the Sultan’s initial pledge was, in fact, reduced in deference to diplomacy. It is further true that many foreign nationals, including at least one Irish physician, served in both Topkapı Palace and the Sublime Porte (the administrative seat of the Ottoman government) during the reign of Abdülmedjid i between 1839 and 1861. To what extent, if at all, this son of Ireland influenced the Sultan’s decision to send aid, however, is unclear. Even murkier are the details of the ships and their connections, if any, to the town’s symbolic star and crescent.

News of a “blight of unusual character” ravaging potato fields on Britain’s Isle of Wight first reached the desk of University of London botanist John Lindley in August of 1845. As editor of the Gardner’s Chronicle and Horticultural Gazette, Lindley expressed guarded concern, and he requested that his readers submit any further information about the blight. But later that month, when the catastrophe hit closer to home, leaving “hardly a sound [potato] in Covent Garden market,” as Lindley observed, his tone shifted to alarm: “A fearful malady has broken out among the potato crop. On all sides we hear of the destruction.... As for cure of this distemper, there is none.... We are visited by a great calamity.”

If the English were alarmed, that was nothing compared to the panic that gripped Ireland by autumn. Seemingly unstoppable, the disease wiped out one-third of the crop that was practically the sole source of nourishment for more than 3 million of Ireland’s lower classes. The cause of the blight—unknown to Lindley and his Dublin-based colleagues who desperately sought a remedy—was the fungus Phytophthora infestans, which first appeared as whitish patches on the plant’s withering leaves. The disease’s airborne spores then spread rapidly, reducing fields of healthy tubers within hours to rotting heaps of blackened mush, the stench of which was unbearable. The following year was even worse as the blight rampaged across the island. The loss of tens of thousands of hectares, as one shocked witness recorded, was but “the work of a night.”

|

| |

The population’s over-reliance on the potato compounded the crisis. A New World crop, potatoes were introduced to Ireland during the late 16th and early 17th centuries by English colonists. At first, they were considered an upper-class delicacy. By 1800, a fleshy, knobby variety known as the “lumper” potato—ideally suited to Ireland’s cool, wet climate—had replaced oatmeal as a dietary staple among the poor and working class. Cheap, high-yielding and nutritious, lumper potatoes, when mixed with a little milk or buttermilk, provided enough carbohydrates, protein and minerals to sustain life, presuming enough were eaten. Thus, the average Irish male ate 45 potatoes a day; an average woman, about 36; and an average child, 15. Deeply entrenched in Ireland’s economy and lifestyle, the potato was, in the words of a traditional Gaelic folk song, adoringly praised as Grá mo chroí (“Love of my heart”).

|

|

| bridgeman images |

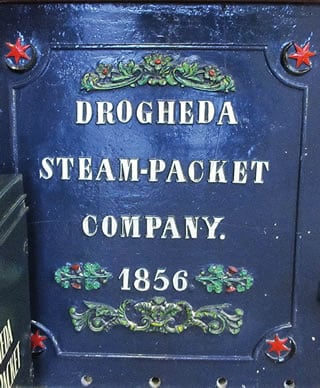

| Top: A decorative metal grid of the Drogheda Steam-Packet Company, founded in 1826 and by mid-century the city’s dominant maritime business, is ornamented in each corner with the town’s crescent-and-star ensign (that here shows a six-pointed star). That it looks so much like the crescent and star of the Turkish flag, above, led to inaccurate stories that, according to Drogheda historian Brendan Matthews, began to circulate in the 1930s linking the town’s symbol with civic gratitude for Turkish aid. |

Despite the loss of this beloved and critical resource, Ireland was by no means bereft of food. Indeed, its farms and pastures abounded with pigs, cattle and sheep, as well as wheat, barley, oats and vegetables; its streams, rivers, lakes and coastline teemed with fish. The cruel irony was that most of this bounty was off-limits to the starving populace.

The best land in Ireland, which was then part of Great Britain, was owned by wealthy British and Anglo-Irish families, many of whom did not live in the country or, if they did, rarely strayed far enough from the urban districts of Dublin to set foot on their agricultural estates.

“Much of Ireland’s ruling class came to take no more interest in the land they owned than they would in the affairs, say, of the South American mines in which they owned stock,” observed historian Tim Pat Coogan in The Famine Plot: England’s Role in Ireland’s Greatest Tragedy.

Further distancing the upper classes was the 1801 Act of Union that dissolved the Irish Parliament and placed the affairs of the country in the hands of distant London politicians. While some British Members of Parliament (mps) were genuinely concerned for Ireland’s welfare, most had little understanding of, let alone sympathy for, its people. To the most calloused, the Irish were “a class which at best wallows in pigsties,” as the London Times described them in January 1848.

Removed both geographically and culturally, many “absentee landlords,” as they were known, leased their properties to local wealthy farmers called “middlemen.” Like the families that hired them, the middlemen notoriously cared little for the estates they managed beyond their revenue-generating potential and, in turn, they sublet them to tenant farmers at often usurious rates. The tenant farmers, primarily in the eastern province of Leinster, further subdivided the land by leasing plots to landless laborers called “cottiers” who paid rent by working a certain number of days on the landlord’s farm. In the west, in Connacht, tenant farmers themselves subleased even smaller plots, called conacre land, to itinerant laborers, charging them twice the rate the tenant farmers paid to the middlemen.

In both systems, it was Ireland’s poorest who bore on their backs the weight of the country’s economy. During the years of the Napoleonic Wars, from 1803 to 1815, times were fairly good: Cut off from trade with central Europe because of the conflict, Britain turned to Ireland for foodstuffs and manufactured goods. But successive population explosions and the end of the wars left Ireland with a surplus of people and a dearth of jobs. By the 1840s, families that may have once had plenty now found themselves eking out subsistence livings by coaxing crops of potatoes from between parallel, flat-topped rows of heaped earth called “lazy beds,” a farming method known in Ireland for 5,000 years, since the Bronze Age. Hunting game or fishing in lakes or streams was criminal poaching, and fishing along the coast was a seasonal operation that required a boat and tackle. When the blight struck in 1845, many people pawned or sold what fishing equipment they had to raise money for food, never dreaming that the following year would be even more disastrous.

Yet even as Ireland starved, most of the food produced on its farms continued to be exported to England, with the profits lining pockets for landowners. In the heated words of Irish revolutionary John Mitchell, who spoke more than two decades later in 1868, “God sent the blight, but the British sent the famine.”

|

|

| Drogheda’s ensign has appeared variously with stars of five, six and seven points: Drogheda United Football Club, top, displays five; the almshouse of St. John, above and in detail below, below, shows seven. The emblem originated in Byzantium, where the star showed eight points. English King Richard (“the Lionheart”) adopted the crescent and star in 1192 upon his capture of Cyprus from Byzantine rule and bestowed it, two years later, on the port of Drogheda. |

|

Modern historians, especially revisionists such as Coogan, sympathize with Mitchell’s view, insisting that “The Great Hunger” is the more accurate term, since “famine” implies a shortage of food, which was not the case.

“There was plenty of food being produced and shipped out, but the people who grew it couldn’t afford to buy any of it,” says John O’Driscoll, curator of Ireland’s Famine Museum at Strokestown Park in County Roscommon.

When tenants couldn’t pay the rent—having spent whatever money they had and sold everything they owned to buy food—they were evicted, at the landlord’s behest, by armed officials. To prevent tenants from returning, wrecking crews burned their cottages or reduced them to rubble. Witnessing such a scene, Strokestown parish priest Father Michael McDermott angrily wrote a letter to The Evening Freeman, published in December 1847: “I saw no necessity for the idle display of such a large force of military and police ... surrounding the poor man’s cabin, setting fire to the roof while the half-starved, half-naked children were hastening away from the flames with yells of despair, while the mother lay prostrate on the threshold writhing in agony, and the heartbroken father remained supplicating on his knees ... thus leaving the wretched outcasts no alternative but to perish in a ditch.”

And perish they did. Even though the crop of 1847 was blight-free, the harvest was simply not large enough to feed the population. As recorded in Ireland’s Census of 1851, deaths from starvation between 1844 and 1847 skyrocketed in most counties: from 8 to 480 in Roscommon; from 51 to 927 in Mayo; from 15 to 586 in Kerry—hence the dire epithet, “Black ’47.”

Some responded in anger, incited by the likes of Mitchell, and riots ensued in many of Ireland’s towns and major cities as roving gangs and mobs looted homes, shops and warehouses. Others chose emigration, scraping together what pennies they could to pay for passage to America with hopes for a better life. In 1851 alone, a quarter of a million Irish immigrants journeyed to the u.s. and settled primarily in Boston and New York where, by 1855, a third of the population was Irish-born.

For those emigrating, the shipping hub of Liverpool, England, was typically their port for trans-Atlantic passage. Among the Irish cities offering regular steamship service to Liverpool was Drogheda, which became Ireland’s second largest port of emigration, after Dublin.

“The number making their way by Liverpool through this port of Drogheda to America exceeds that of any former year,” reported the Drogheda Argus in February 1847, a year in which as many as 70,000 people emigrated from Drogheda’s docks. “Every day the town ... is crowded with cadaverous looking emigrants [and] unfortunate creatures who ... present an appearance absolutely frightful. Women and children have been seen actually contesting with cattle for pieces of raw turnips which were lying on the Steam Packet Quay.”

And even as such scenes played out, export ships in ports throughout Ireland groaned under the weight of food.

“Would to God that you could stand for one five minutes in our street, and see with what a troop of miserable, squalid, starving creatures you would be instantaneously surrounded, with tears in their eyes and misery in their faces,” wrote Kenmare parish priest John O’Sullivan in a letter to Charles Trevelyan, Britain’s assistant secretary to Her Majesty’s Treasury, in December 1847. “Whatever be the cost or expense, or on whatever party it may fall, every Christian must admit, that the people must not be suffered to starve in the midst of plenty.”

Trevelyan, however, was not among the Christians who shared O’Sullivan’s views, believing instead that the blight was sent by God as an opportunity for Ireland’s “moral and political improvement.”

Yet far to the east, there was a ruler who heeded the spirit of O’Sullivan’s plea.

ultan Abdülmedjid i was 24 years old in 1847. Having acceded to the Ottoman throne at 16, he would rule the empire, which reached from Morocco to Central Asia, until his death in 1861 at age 39. He was a calligrapher, fluent and literate in Arabic, Persian and French; a devotee of European literature; and a lover of classical music and opera, the sounds of which drifted from his tent on imperial outings. He also shared a keen interest in the latest advancements in western science, medicine and technology. After witnessing a demonstration of Samuel Morse’s new invention, the telegraph, at Istanbul’s Beylerbeyi Palace in 1847, he conferred upon the inventor the Nishan Iftichar (Order of Glory) and delighted in personally transmitting a message between the harem and the palace’s main entrance.

ultan Abdülmedjid i was 24 years old in 1847. Having acceded to the Ottoman throne at 16, he would rule the empire, which reached from Morocco to Central Asia, until his death in 1861 at age 39. He was a calligrapher, fluent and literate in Arabic, Persian and French; a devotee of European literature; and a lover of classical music and opera, the sounds of which drifted from his tent on imperial outings. He also shared a keen interest in the latest advancements in western science, medicine and technology. After witnessing a demonstration of Samuel Morse’s new invention, the telegraph, at Istanbul’s Beylerbeyi Palace in 1847, he conferred upon the inventor the Nishan Iftichar (Order of Glory) and delighted in personally transmitting a message between the harem and the palace’s main entrance.

In addition to his enthusiasm for innovation, Abdülmedjid i became known also for charity. Sickly as a child, he wished to spare his subjects the ravages of infectious diseases. During his official tours of the empire, for example, he would have village children vaccinated in his presence.

In addition to his enthusiasm for innovation, Abdülmedjid i became known also for charity. Sickly as a child, he wished to spare his subjects the ravages of infectious diseases. During his official tours of the empire, for example, he would have village children vaccinated in his presence.

Politically, he was just as progressive. Determined to modernize the empire, the young Sultan set about instituting the wide-reaching tanzimat (“reorganization”) envisioned by his father, Sultan Mahmud ii. This included abolishing executions without trials, issuing the first Ottoman banknotes, laying the foundations of the first Ottoman Parliament and establishing a system of modern, secular institutions, schools and universities under one umbrella, the newly formed Ministry of Education. Hoping to dampen ethnic nationalism, he extended full citizenship and equality before the law to all Ottoman subjects, regardless of ethnicity or religion. At court, he swept aside centuries of onerous etiquette: No longer would foreign emissaries have to check their ceremonial swords at the door, be doused in rosewater, wear kaftans over their uniforms and sit lower than the Sultan—if allowed into his presence at all.

“An ambassador under the new regime stood, with sword by his side and cocked hat in hand, face-to-face with the Sultan,” reported one British envoy.

Among those who enjoyed such free and familiar access to Abdülmedjid was English Ambassador Stratford Canning, son of an Irish-born London merchant. Canning admired the young Sultan’s ambitions, but as one of the longest-serving diplomats in the Ottoman court, he took the long view of their odds.

“He was a soft-natured, intelligent, work-conscious, dignified but humble man enriched with compassion,” Canning observed. “But he lacked the power and initiative to turn his wishes into reality.”

Ultimately, Abdülmedjid proved Canning wrong and might have gone on to achieve even greater reforms had he not succumbed to tuberculosis at such an early age. He was frail his entire life, and his poor health may have been why he surrounded himself with doctors—foreign doctors in particular—though according to historian Miri Shefer-Mossensohn, such indulgences were both common and fashionable.

“French, Germans, Italians. The Ottomans always had European physicians with them, [together] with their own Ottoman doctors, dating back to the 15th century,” says Shefer-Mossensohn, author of Ottoman Medicine: Healing and Medical Institutions, 1500-1700. The rationale, she points out, was essentially one based on probability: “The idea was, you don’t know which physician is going to make you better, so let’s have as many as we can and employ a variety of all skills.”

The record shows that among Abdülmedjid’s personal team of specialists was Julius Michael Millingen, a Dutch-English doctor who ministered to Lord Byron on his deathbed, a Viennese anatomist named Spitzer—and an Irish physician from Cork named Justin Washington McCarthy. Born the son of a barrister around 1789, McCarthy was hailed on September 8, 1841, in his hometown newspaper, the Cork Examiner, as “one who has long attained considerable eminence as a physician in the Turkish capital.” He trained in Edinburgh and Vienna before entering the service of the Ottoman court under Abdülmedjid’s father more than a decade earlier.

The first mention and earliest evidence of McCarthy’s connection with the story of the Sultan’s food aid to the Irish appears in the diary of Irish writer and patriot William J. O’Neill Daunt. Writing from Edinburgh on January 17, 1853, some six years after the event described, Daunt recollected that “A Mr. M’Carthy [sic] came. His father is physician to the Sultan.” In the next day’s entry, he reported, “M’Carthy (the Turk) ... told me that the Sultan had intended to give £10,000 to the famine-stricken Irish, but was deterred by the English Ambassador, Lord Cowley, as Her Majesty, who had only subscribed £1,000, would have been annoyed had a foreign sovereign given a larger sum.”

Details in Daunt’s story stand up. Queen Victoria in 1847 originally sent only £1,000 before later doubling her pledge. (For her parsimony, the Irish press rewarded her with the sobriquet “the famine queen.”)

|

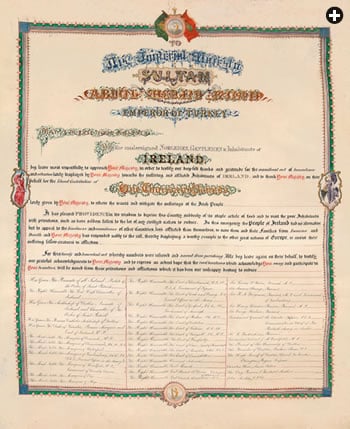

| ottoman archives / courtesy of mustafa ÖztÜrk akcaoĞlu |

| In addition to financial aid from Sultan Abdülmedjid i, in May and June of 1847, three Ottoman ships arrived in Drogheda. Two came from the Ottoman port of Thessalonica, laden with corn, and one came from Stettin bearing red wheat. Although it is still unclear to historians whether these ships arrived with donations or merely commercial shipments, the Irish eloquently expressed their gratitude in this ornate letter, which is now part of the Ottoman Archives in Istanbul. A copy of it is kept by the National Library of Ireland. |

McCarthy did have two sons, both born in Istanbul, although which son was in Edinburgh that year remains unknown. Lord Cowley was the Hon. Henry Wellesley, Ambassador Canning’s chargé d’affaires, who served as acting ambassador in 1847 while Canning was on leave in England. Additionally, the bit about the Sultan reducing his donation out of deference to the British Crown appeared in print at least three years earlier, in the October 1850 issue of The New Monthly magazine, a London-based journal of arts and politics. Writing from Smyrna (modern Izmir), on Turkey’s Aegean coast, correspondent Mahmouz Effendi praised “young Sultan Abdul-Medjid, who, in the recent Irish famine, contributed the handsome donation of 1,000l. sterling to relieve the distresses of those whom his own creed regards as infidels ... and who would have given more, much more, but that state etiquette was quoted to show the reigning sovereign of England must, in these cases, be permitted to head the list.”

Dispatched during the ominous buildup to the Crimean War (1853-56)—when Russian threats inspired an Ottoman alliance with England—Effendi’s report further speculated that “[i]f there’s an Irishman” serving under Admiral William Parker, commander of the British Mediterranean fleet, “we feel sure that the son of the Emerald Isle will, in the moment of battle, remember the Sultan’s well-timed and noble generosity; and be the enemy whom it may, Paddy in mere gratitude will then strike hard and home!”

While there is no evidence that McCarthy the physician personally informed the Sultan of the famine, there would have been no need. Since 1847 the devastation had been worldwide news that inspired equally global outreach.

|

| On April 21, 1847, the London Times praised the gift, briefly. |

“There was an incredible international relief effort, with contributions coming in from all across the world, from Caracas to Cape Town to Melbourne to Madras,” says Christine Kinealy, director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University in Connecticut. While the British government—primarily under Trevelyan’s more sympathetic predecessor, Sir Robert Peel—was providing millions of pounds of relief in the form of various programs such as workhouses, Kinealy notes that private donations also “played a significant part” in the overall effort. Foremost among private donors were securely middle-class English and American Quakers who helped establish soup kitchens in various Irish towns and cities. Yet the most moving and impressive foreign donations, Kinealy points out, came from those who were equally as poor as the famine-stricken Irish.

“In India, there were carpet-sweepers, who were the lowest-paid workers in the country, who sent money to Ireland. In America, the Choctaw and Cherokee Indian nations also sent money,” she says.

Entrusted with channeling private donations was the British Association for the Relief of Distress in Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland, which was commonly known as the British Relief Association, or bra, and was established in January 1847. In its annual report of 1849, the organization commended “His Imperial Majesty, the Sultan, a subscriber of 1,000l., whose munificent example was followed in his own and other states by many, whose sole ties with the people of Great Britain were those of sympathy, humanity and the brotherhood of mankind.” Other contributions from within the Ottoman Empire included a general collection taken up in Constantinople amounting to £450.11s. and £283 sent by the local chapter of the Conference of St. Vincent de Paul (svp), a Catholic charity.

|

| The Drogheda quay today, along the Boyne River, near its mouth on the Irish Sea. |

The bra report included the transcript of a letter, now stored in Istanbul’s Ottoman archives, in which a host of Irish gentry and clergy thanked Abdülmedjid i for his generosity. The text of the highly stylized document, written on vellum and decorated with shamrock-and-heather motifs, commends the Sultan for aiding “the suffering and afflicted inhabitants of Ireland,” and “displaying a worthy example to other great nations in Europe.” Flattered by the letter, Abdülmedjid i reportedly responded: “It gave me great pain when I heard of the sufferings of the Irish people. I would have done all in my power to relieve their wants.... In contributing to [their] relief, I only listened to the dictates of my own heart; but it was also my duty to show my sympathy for the sufferings of a portion of the subjects of her Majesty the Queen of England, for I look upon England as the best and truest friend of Turkey.”

Not surprisingly, hidden in plain sight between the lines of this mutual admiration is diplomacy. The Irish letter respectfully acknowledges the “vast territories” under the Sultan’s influence while Abdülmedjid’s warm characterization of England is a thinly veiled appeal to the Crown for support at a time when Russia’s Tsar Nicholas i was threatening war against him.

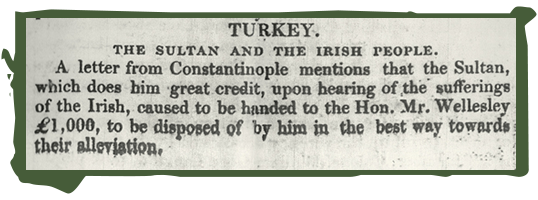

![I would have done all in my power to relieve their wants ... In contributing to [their] relief, I only listened to the dictates of my own heart - Abdülmedjid I](images/irish/inset-2.png) The headlines of the day nevertheless praised Abdülmedjid. “Irish Distress—Turkish Sympathy” declared The Nenagh Guardian on April 21, 1847, while four days earlier Dublin’s The Nation had hailed the friendship between “The Sultan and the Irish People.” Even the cautiously conservative London Times that same day declared that the Sultan’s generosity to the Irish “does him great credit.” Picking up on the story, the English religious magazine Church and State Gazette on April 23 lauded Abdülmedjid as a ruler “representing multitudinous Islam populations,” for his “warm sympathy with a Christian nation.” The article went on to express hope that “such sympathies, in all the genial charities of common humanity, be cultivated and henceforth ever be maintained between the followers of the cross and the crescent!” Six years later, during the Crimean conflict, as some in England questioned the appropriateness of a Christian nation coming to the aid of a Muslim one to thwart Russian ambition, others demonstrated that those “genial charities of common humanity” were indeed not forgotten.

The headlines of the day nevertheless praised Abdülmedjid. “Irish Distress—Turkish Sympathy” declared The Nenagh Guardian on April 21, 1847, while four days earlier Dublin’s The Nation had hailed the friendship between “The Sultan and the Irish People.” Even the cautiously conservative London Times that same day declared that the Sultan’s generosity to the Irish “does him great credit.” Picking up on the story, the English religious magazine Church and State Gazette on April 23 lauded Abdülmedjid as a ruler “representing multitudinous Islam populations,” for his “warm sympathy with a Christian nation.” The article went on to express hope that “such sympathies, in all the genial charities of common humanity, be cultivated and henceforth ever be maintained between the followers of the cross and the crescent!” Six years later, during the Crimean conflict, as some in England questioned the appropriateness of a Christian nation coming to the aid of a Muslim one to thwart Russian ambition, others demonstrated that those “genial charities of common humanity” were indeed not forgotten.

“There seems to be great stress laid upon the argument that the Sultan, not being a Christian ... why should we support him, &c.?” wrote Jack Robinson of Wolverhampton in a letter to the editor of the Daily News in November 1853. “I beg to remind some people ... how very like a Christian he behaved when the famine raged in Ireland.”

hat Abdülmedjid sent £1,000 to Ireland, then, is well documented. But what of the ships loaded with grain? Here, teasing fact from fiction becomes more difficult, yet there is circumstantial evidence to suggest that his gift may have exceeded £1,000.

hat Abdülmedjid sent £1,000 to Ireland, then, is well documented. But what of the ships loaded with grain? Here, teasing fact from fiction becomes more difficult, yet there is circumstantial evidence to suggest that his gift may have exceeded £1,000.

|

| Today, nearly 70,000 people live in Drogheda and its environs, including many who commute to Dublin. As a historic port, it has long been infused with influences from abroad, such as fast-food grilled kebab-—a staple of Turkish cuisine |

A July 21, 1849, article in the American news weekly The Albion stated that “the Sultan originally offered to send £10,000 to Ireland, as well as some ships laden with provisions” (emphasis added). A similar story, “Royal Etiquette and Its Consequences,” on page two of the September 29, 1849, edition of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, reported that “whilst famine was doing its deadly work in Ireland, the Turkish Sultan, Abdul Medjid Khan, proposed to make a donation of ten thousand pounds, and to send vessels laden with provisions, for the relief of the starving Irish” (again, emphasis added). In the fourth volume of Life and Times of Sir Robert Peel, published in 1851, biographer Charles Mackay makes the same claim: that the Sultan intended to send £10,000 “besides some ship-loads of provisions.” Some years later, in 1880, Irish patriot Charles Stewart Parnell—no friend of the British Crown—put an even finer point on the matter: Victoria, he claimed, had the Turkish grain ships intercepted along with their cargo, valued at £6,000. Parnell further declared that Victoria sent Ireland no money at all—which does cast doubt on his whole story. His false claims were immediately rebuked by none other than Lord Randolph Churchill—father of Winston—as part of an ongoing feud between the two men that played out in the pages of the English and Australian press. More recently, Irish author Ted Greene, in his commemorative volume Drogheda: Its Place in Ireland’s History, published in 2006, makes the unattributed assertion that Victoria “stepped in by preventing the ships entering, first Cobh [Cork], and then Belfast harbour but they finally succeeded to dock secretly in the small port of Drogheda and deliver the food’” (original emphasis).

From “some ships laden with provisions” to three ships “secretly” docking in Drogheda, the story has grown over the years from what may have been an unrealized gesture on Abdülmedjid’s part—to add some food to his donation of money—to a covert operation to slip shiploads of grain past British customs authorities. In either case, this particular chapter of the story raises doubts in Kinealy’s mind.

“It just doesn’t make sense. If he was asked not to give more than the Queen, and wanted to have a closer alliance with Great Britain, why would he risk sending three ships surreptitiously with the potential to offend his ally?” she contends.

But from a Turkish Muslim point of view, says Ahmet Öǧreten, assistant professor of history at Kastamonu University in northern Turkey, the move made sense.

“It was a common custom among Muslims that if you said you are giving a donation, but are only permitted to give part of it, you don’t take the rest of the money back. You find a way to deliver the whole donation, one way or another,” says Öǧreten, who is preparing a study on the episode. His belief that the Sultan would have made good on his original pledge out of a sense of religious duty is reflected in the Reverend Henry Christmas’s 1854 biography of Abdülme djid. “I am compelled by my religion to observe the laws of hospitality,” Christmas quoted the Sultan as saying, in response to an influx of Polish and Hungarian refugees fleeing Austrian and Russian aggression. The Protestant minister cited this, together with the story of the gift to the Irish, as examples of Abdülmedjid’s “true spirit of Christianity, and there is more of it in the Mohammeden [sic] Sultan of Turkey than in any or all of the Christian princes of Europe.”

Searching archives in Ireland and Istanbul, Öǧreten has, at the very least, uncovered evidence that suggests the Sultan’s donation was, in fact, somewhat larger than was publicly reported.

“A document in the Ottoman archives records he donated 1,000 Turkish lira, not 1,000 [British] pounds,” says the professor. The document concerns a request by a man who was identified as the one who presented the Irish letter of gratitude to the Sultan, “Mosyo O’Brien”—possibly Sir (“Monsieur”) Lucius O’Brien, a signatory to the letter. Whether it was a slip of the pen, or a figure lost in translation, the amount noted in the document is “1,000 Lira,” which Öǧreten points out would have been worth more at the time than £1,000. With an 1847 exchange rate of £1.20 to one Ottoman lira, Abdülmedjid’s donation of 1,000 lira (£1,200) would, in today’s currency, be close to $160,000.

Whatever the amount, how a distant Muslim ruler became a hero in the annals of Drogheda ultimately comes down to a confluence of circumstances, including, finally, the coincidental role played by the town’s crest that uses a star and crescent, according to Drogheda historian Brendan Matthews, author of the study, “Drogheda & The Turkish Ships of 1847.”

“The symbol of the Drogheda Steam Packet Company, the private company that offered regular steamship service to Liverpool out of Drogheda, was a green flag with a white, five-pointed star set above a crescent moon,” explains Matthews. The company adopted this banner, which today has become synonymous with Islamic heritage, not from the Ottomans, but from Drogheda’s town crest that has featured the star and crescent since the late 12th century.

|

| In 1995, William Frank, then mayor of Drogheda, recognized the Sultan’s aid with this commemorative plaque over the entrance of the Drogheda Hotel, which is the same hotel that may have housed Ottoman sailors responsible for the distribution of corn and wheat. |

“They were bestowed on Drogheda by Richard the Lionheart in 1194,” says Matthews. King Richard adopted the symbol in 1192 upon capturing Cyprus from its last Byzantine ruler while en route to the Holy Land during the Third Crusade. The original symbol—a merging of the crescent moon of ancient Byzantium’s patron goddess Diana with the eight-pointed star of the Virgin Mary—had been used by Byzantine rulers since the fourth century. It did not become an emblem of Islam until after the 14th century.

Meanwhile, from 1846 to 1847, commercial grain imports to Ireland more than quadrupled from 197,000 tons to 909,000 tons. Among the ports that experienced this sudden influx of foreign grain—Ottoman grain, in particular—was Drogheda. “Previous to the famine of 1847, the foreign commerce of Drogheda was ... confined to a few cargoes of Baltic and American timber,” wrote Anthony Marmion in his Ancient and Modern History of the Maritime Ports of Ireland, published in 1853. “Since then, however, and for the last four years in particular, there has been a considerable trade in the import of foreign wheat, but more particularly in Indian Corn from the Black Sea.”

This expansion was part of the rise in Ottoman-European commerce resulting from Abdülmedjid’s tanzimat, which established a Ministry of Trade that sought “to forge new trading linkages with the dynamic industrializing economies of western Europe,” according to historian Mark Mazower, author in 2006 of Salonica, City of Ghosts. Carter Vaughn Findley, in his 2010 study Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity, observed that between 1840 and 1876 this trade liberalization led to an increase in the value of Ottoman exports from £4.7 million to £20 million—exports Findley noted were comprised “disproportionately of Balkan agrarian products.”

|

Combing period newspapers, Matthews learned that three ships from the Balkan regions docked at Drogheda in May 1847, within a month of Abdülmedjid’s publicized gift. Two of the ships, the Porcupine and the Ann, carried Indian corn from Thessalonica (Salonica), while the third, the Alita, brought red wheat, also known as “Turkey red wheat,” from Stettin, a Baltic seaport in what is now Poland. While Matthews does not go so far as to suggest these were the three so-called “secret ships,” he does speculate that the coincidental convergence of grain-bearing ships from the Ottoman Empire, the star-and-crescent flag of the Drogheda Steam Packet Company and the desperation of the people thronging the docks may well have provided the legend with its seeds.

“You had these ships coming in from the Ottoman Empire with Sardinian and Egyptian and Greek sailors on board, who were well aware of the star and crescent symbol of the Ottomans. You had 70,000 starving Irish people crowding the quay in search of work, or food, or a way to get out of the country. And then you had these local ships flying a flag with the star and crescent, which the Ottoman sailors could readily identify with,” Matthews summarizes. These circumstances, he speculates, may have led to a spontaneous humanitarian gesture on the part of the sailors who may have given some of the grain directly to the starving Irish, either out of pity or some vague sense of kinship with a port where the star and crescent flew from the masts of local ships.

“Perhaps they gave them 100 bags of food? Twenty bags of grain, to feed 100 families? Something happened that led to this story in our oral history: that in this time of crisis, we got food from the Turkish people,” Matthews says.

As the story was handed down from generation to generation, Matthews believes, it was embellished with tales of “secret” ships and the “adoption” of the “Turkish” star and crescent by grateful town officials. Such embellishments, he surmises, were likely added in the telling and the retelling—a credible by-product in a culture famed for its oral tradition that, as Julius Caesar noted in his Gallic Wars, favored the “employment of the memory” over the written word.

Whatever the truth, this chapter in the history of “The Great Hunger” has nonetheless been immortalized in paint and in stone, and may yet be made into a feature film—should the ambitions of Turkish producer Omer Sarikaya be fulfilled. (See sidebar, opposite.)

Yet, at its heart lies the undisputed fact of a generous gesture on the part of an Ottoman ruler toward a people to whom he owed nothing but the mercy required of him by faith and personal character.

|

Connecticut-based freelance writer Tom Verde (writah@gmail.com) is a regular contributor to AramcoWorld. |