On Samos, a speck of a Greek island off the Turkish coast, one of the oddest treasures on display in the Archeological Museum is a locally discovered, bronze mace-head depicting the frightful demon Pazuzu.

|

| necklace: bruce white / museo arqueolÓgico de sevilla; cauldron: bruce white / cyprus museum; statue: british museum |

| Top-left: Around 700 bce, the Phoenician settlement of Spal, a predecessor of Seville, Spain, was large and established enough that its priests used this sumptuous, intricate and heavy gold necklace for rituals. Part of the four-piece Carambalo treasure, it shows the high art that Phoenicia spread throughout the Mediterranean. Above-left: Dated slightly earlier and resembling others from Greece and Anatolia is a bronze cauldron from Tomb 79 in Salamis, Cyprus, that features eight griffin and four siren-men protomes. Above-right: Under Ashurnasirpal ii, the Neo-Assyrian empire began its expansion west to the Mediterranean. This 113-centimeter (44 ½") magnesite statue is a rare sculpture in the round from the period. |

It came from Mesopotamia, more than 1500 kilometers to the east. In Tuscany, Italy, equally fearsome lion heads, imported from the kingdom of Urartu in what is now Armenia and eastern Turkey, ring the tops of bronze cauldrons. In the waters off southeastern Spain, a recently excavated shipwreck yielded African elephant tusks inscribed with the names of Phoenician gods. These prizes likely came from a Phoenician colony near Seville or Cádiz, some 4000 kilometers from the heartland of the Phoenicians at the eastern end of the Mediterranean. And these same seafaring merchants can be thanked for the very existence of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, which were written down from oral tradition between the eighth and the sixth centuries bce, after the Greeks had adopted the Phoenicians’ clever idea of writing by using an alphabet.

It was the start of the Iron Age, the first half of the first millennium bce, long before “globalization” and the Internet came to define our own hyper-connected era, and trade routes had already woven the Near East, North Africa and the Mediterranean into a highly complex, deeply symbiotic web of cultures. By Homer’s time, around the beginning of the millennium, there was a flourishing, intercontinental trade in exquisite gold, jewelry and ivory, exotic cult objects, intricately crafted furniture and polished silver bowls masterfully incised with elaborate scenes of heroic hunting and battle, as well as more ordinary wares.

|

| WILLIAMS COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART |

| Likely carved early in Ashurnasirpal ii’s 24-year rule (probably in 880 bce), this winged figure was among the gypsum bas-relief frescoes that decorated the Northwest Palace at Nimrud, the first Neo-Assyrian location in which such frescoes are known to have been produced. The cuneiform script in the middle records the ruler’s lineage and describes the city and palace. Originally, it was brightly painted. |

The kingdoms, territories and cultures were many, but there was one major driving force behind these exchanges: the Neo-Assyrian empire. At its height in the seventh century bce, it stretched from its capital at Nineveh in present-day Iraq to encompass Babylonia and western Iran, northern Egypt, the Levant and Anatolia. Heir to the less extensive—and less voraciously expansive—Assyrian empires of the third and second millennia bce, it nevertheless did not project itself into the Mediterranean. To reach west, the Neo-Assyrians allied with the Phoenicians, who brought back tribute, carried on maritime commerce and searched for resources.

Fueling much exploration was the search for iron, which proved superior to bronze for tools and weapons. Phoenician sailors and traders established posts across the ancient world, including the North African coast at Carthage, the major islands of the Mediterranean and along both the southern and western coasts of Iberia (now Spain and Portugal).

Even King Midas, who was a real sovereign in seventh- or eighth-century bce Phrygia (now Turkey), played a part in intercultural diplomacy. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Midas was the first foreign ruler to pay homage to the prophetic oracle at the Greek sanctuary of Delphi. This journey took him across the Aegean Sea some 800 kilometers west. Although legend has it that everything Midas touched turned to gold—perhaps the story pertains to an earlier king also named Midas, but no one is quite sure—the majestic throne he bestowed on the oracle at Delphi was made of wood and ivory. A figurine that helped decorate this continent-spanning gift, 35 centimeters (9") tall and bug-eyed, with his left hand resting on a tamed lion and the right grasping a spear in a traditional “Master of Animals” stance, stood this winter among other prize objects in the exhibition “Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age” at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

| JURGEN LIEPE / BPK / VORDERASIATISCHES MUSEUM, STAATLICHE MUSEEN ZU BERLIN / ART RESOURCE |

| Found as far west as Italy and east to Iran, intricately carved Tridacna squamosa shells made for coveted luxury cosmetic containers. This one, carved on both sides, its hinge fashioned to resemble a human head, is dated to the seventh or sixth century bce, and it was found in Assyrian house 58 in Ashur. |

“We think of ourselves as living in a global age, but really you have to look far back in time to see how closely people interacted,” explained exhibition curator Joan Aruz as she guided me around the galleries. The first millennium bce was the first era in which the arts and goods from different cultures were transported across three continents—much of it from western Asia (the Near East) and Africa to southern Europe, she said.

“You have to understand this phase in order to appreciate what came afterwards, but most people are unaware of what was going on before the Greek classical period. They think it just emerged out of the head of Zeus, like Athena,” she added with a laugh.

Taking a broad measure of the wide-ranging debt the western classical world owes its mostly Near Eastern antecedents, the exhibition's focus lay not on individual kingdoms or states, not on life in Assyria or Phoenicia, Egypt or Judah, Elam, Urartu, Greece, Etruria or Iberia—the list goes on—but on what linked them all: artistic, cultural, economic and religious exchanges. Over the five years it took to develop the show, Aruz and her colleagues selected and secured some 260 objects from 41 museums and institutions in 14 countries. Staging a exhibition restricted to a single civilization would have been child’s play by comparison.

Aruz and her team brought ample experience to the challenge. “Assyria to Iberia” was the third in a series of major exhibits telling the stories of early arts and trade from the Indus valley in the east to the westernmost reaches of the Mediterranean. In 2003, “Art of the First Cities” examined Mesopotamian and Sumerian cultures in the third millennium bce. “Beyond Babylon,” the second episode that followed in 2008, looked at the dominant Babylonian empire of the second millennium bce. This latest installation encompassed the first half of the first millennium, the early Iron Age, when Assyria controlled the Near East until the Babylonians and the Medes overthrew it at the end of the seventh century bce.

It was a war-ravaged era, but also one of tectonic cultural ferment. The period brought a deluge of Near Eastern art styles, religious and mythic symbols and imagery, as well as new techniques for fashioning gold, silver, bronze, glass, pottery and stone, surging westward, carried largely by Phoenician merchants, itinerant artisans and Greek mercenaries. The Mediterranean was awash in sculptures of snarling bronze griffins, striding sphinxes, voluptuous goddesses, fantastic bird men and triumphant kings. Many of the creature-images had apotropaic functions, that is, they were talismans, placed on wall reliefs, furniture, cauldrons and other objects to ward off evil.

Like its predecessor exhibits, much in “Assyria to Iberia” was both revisionist and expansive, a story writ large that heightened awareness of the richness of the arts and cultures of the Near East and, most of all, their pervasive influences on the esthetics of what later emerged as the western classical world. “The public at large is more focused on current events and doesn’t realize what vital centers of culture these places were,” Aruz pointed out. For example, she added, the area of Mosul, Iraq, hotly and painfully contested in recent years, was the heartland of the Neo-Assyrian empire.

|

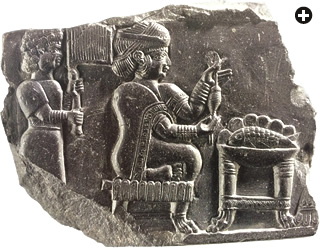

| MUSÉE DU LOUVRE / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES |

| Domestic tableaux are rare for the eighth and seventh centuries bce: Most images of the time were devoted to gods, rulers and warfare. This Elamite bas-relief, carved in a bitumen compound, shows a woman seated on a chair, her feet daintily folded beneath her, proudly holding up a threaded spindle; a servant with a fly-wisk stands behind her. Its realism and simple humanity impart a glimpse into a private domain in the distant past. |

Ambitious as it was, the exhibition could not cover everything. The presentation only touched on the extensive and powerful Arabian spice routes, for instance, although intriguing scholarly tidbits surfaced during symposia in conjunction with the exhibition. Aruz herself was particularly enthused about a recent find at Megiddo in Israel, in which traces of cinnamon were identified inside Phoenician jars. “When you realize this cinnamon came from Southeast Asia, it’s just amazing to see how far these people were traveling along the spice routes,” she explained.

The exhibition also brought welcome attention to rarely viewed artifacts from lesser-known, far-flung local collections, including islands such as Samos, Rhodes and Sardinia, as well as Yerevan in Armenia and others. In addition, out-of-sight pieces in well-known institutions like the British Museum and others were brought out of storage and placed on view often for the first time in decades, if ever. Time and again during our tour, Aruz introduced an object by saying that few people, if anyone, had seen it before. Quite a number, she said, she discovered by chance while visiting a museum to inspect a known object only to stumble, happily, across others either on display or languishing in the basement. With this exposure, these smaller museums are likely to attract more visitors and scholars, she predicted.

|

| BRITISH MUSEUM |

| An unflinching chronicle of conquest, this nearly panoramic bas-relief depicts the victory of Neo-Assyrians over the Elamites in about 653 bce at Til Tuba, now in Iran. Inscribed only a few years after the battle on limestone panels, each taller than a person, in Nineveh’s Southwest Palace, it uses more than a dozen sequential scenes, some of which are explained in cuneiform captions, to tell the story of the battle. |

Occasionally, Aruz’s archeological sleuthing had more than a whiff of Indiana Jones. Unlike the cinematic tomb raider, however, Aruz wielded neither a whip nor a trained monkey, but her museum’s prestige. This secured more easily the numerous items from museums that had lent the New York institution objects for previous exhibitions, and it opened new doors—literally, in one case. Although Granada’s archeological museum has been closed for decades, she brushed this inconvenience aside and arranged to view pieces she had heard about from colleagues: alabaster jars transported to Iberia all the way from Egypt to serve as burial urns in a Phoenician cemetery. One jar even bore the jowly visage of Bes, the ancient Egyptian deity invoked to safeguard mothers, children and households.

London’s British Museum presented an opposite challenge. With holdings so vastly numerous, so encyclopedic, many antiquities remain out of sight, including, it turned out, a uniquely intimate banquet relief of Assyrian king Ashurbanipal and his consort. Depicting the couple on their thrones, each raising saucer-shaped drinking cups to toast his victory over the Elamites, this gypsum-alabaster sculpture is one of the few images to show Assyrian potentates not bashing heads, hunting lions or casting baleful gazes upon their subjects. (Nonetheless, the severed head of the vanquished Elamite king dangles from a nearby pine tree, somewhat spoiling the moment of repose, at least to modern eyes.)

London’s British Museum presented an opposite challenge. With holdings so vastly numerous, so encyclopedic, many antiquities remain out of sight, including, it turned out, a uniquely intimate banquet relief of Assyrian king Ashurbanipal and his consort. Depicting the couple on their thrones, each raising saucer-shaped drinking cups to toast his victory over the Elamites, this gypsum-alabaster sculpture is one of the few images to show Assyrian potentates not bashing heads, hunting lions or casting baleful gazes upon their subjects. (Nonetheless, the severed head of the vanquished Elamite king dangles from a nearby pine tree, somewhat spoiling the moment of repose, at least to modern eyes.)

“This stone panel was shrouded in gloom,” said Aruz, “but I immediately realized we had to have it.”

On Samos, the otherwise unassuming antiquities collection revealed another astonishing lode. “What is amazing here is that you walk into a place that is almost never visited and it is absolutely packed with Near Eastern artifacts,” the curator observed. Virtually all of them landed on the island as votive offerings for the temple sanctuary of Hera, the Greek goddess of women and marriage (and the wife of Zeus). Phoenician merchants, Greek mercenaries in the Assyrian army, emissaries and pilgrims from around the Near East and the Mediterranean flocked to the sanctuary, known as the Heraion, and their donations beseeched the goddess’s favor.

|

| (NECKLACE) L’INSTITUT NATIONAL DU PATRIMOINE, TUNIS; (FRAGMENT) METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART; (BOWL) BRUCE WHITE |

| From Assyria, Anatolia and Egypt to North Africa, Greece, Italy and Spain came craft items whose eastern motifs lead historians to refer to them as “Orientalizing” motifs, including this gold necklace, above-left, from Carthage (now in Tunisia) with its Phoenician motifs from mid-seventh to sixth century bce, as well as a conical fragment of a Greek vessel for perfumes found in Italy, which is dated to about 700 bce, top-right. Above-Right: From this same era, and also found in Italy, has come this gilded silver bowl, embossed and engraved with concentric friezes of “Egyptianizing motifs” that combine a variety of Near Eastern themes. |

As a result of such diffuse origins, some items on Samos are like detective mysteries waiting to be solved. A bronze equine chest plate, or frontlet, depicts four female figures and three feline heads. An inscription in Aramaic describes it as a gift to the ninth-century bce king Hazael of Aram-Damascus. The funny thing is that an identical inscription turned up on a matching bronze blinker, used to shield a horse’s eyes, discovered some 325 kilometers across the Aegean in Eretria, north of Athens, where it had been a dedication to another Greek sanctuary, that of Apollo, god of the sun, arts and prophecy. Aruz concluded that both items probably originated in the same set.

|

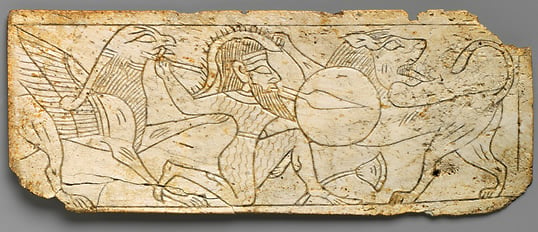

| THE HISPANIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA |

| Around the seventh century bce, Phoenician craft workers near Cádiz and Seville incised and carved numerous ivory and bone objects in Near Eastern styles, including this 13-centimeter (5") plaque that shows a griffin, a hunter and a lion. |

“How could this have happened?” she wondered aloud as we studied the reunited artifacts. One scenario, she proposed, is that Assyrians carried the valuable set of luxury fittings back from Damascus to their capital of Nimrud after defeating Hazael; from there, Greek mercenaries who had fought for the Assyrians brought them as gifts for the gods on their return to their homeland. Or, she speculated, perhaps there were sanctuary officials who traveled, working a network—“the way we look for items on eBay or the Internet”—to seek out valuable dedications for their temples.

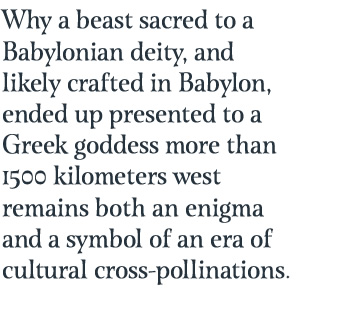

“Both explanations may be true,” the curator suggested. “It’s just mind-boggling to speculate where these objects may have traveled.” Similarly, a 13-centimeter (5") bronze figurine of a mushushshu, a mythical dragon-monster, also surfaced at Samos’s Heraion. Why a beast sacred to the Babylonian deity Marduk, and likely crafted in Babylon, ended up being presented to a Greek goddess more than 1500 kilometers west remains an enigma as well as a symbol of an era of cultural cross-pollinations.

This theme of wide dispersal of similar objects ran throughout the exhibition. A pair of bronze bowls, both a bit more than 21 centimeters (8") in diameter and both bearing finely wrought, standing sphinxes symbolizing Assyria, posed with their paws atop the heads of defeated Asiatic enemies, appear so nearly identical they might have come out of the same Phoenician workshop. But one was unearthed on Crete, and the other at a palace in Nimrud. Perhaps both did originate in Phoenicia, or perhaps an itinerant Phoenician artisan made his way to Crete: The only thing anyone knows for sure is that they are still more evidence of a culturally interwoven world.

|

| THE BRITISH MUSEUM |

| Showing that cross-pollination was nothing particularly new even in the late Bronze Age, this ivory game box depicting a chariot hunt dates from 1250-1100 bce. Found on Cyprus at Enkomi, it displays Aegean, Canaanite, Egyptian and Mesopotamian motifs and styles. |

For the Assyrians, the bloody business of battle, conquest and looting were their strong suits; modesty was not. Slab-like stone plaques, many as tall or taller than a person, like the one in the exhibit picturing a hawk-headed guardian spirit that once was brightly painted, adorned Nimrud’s Northwest Palace. Nearly all bore what scholars call the Standard Inscription exalting Ashurnasirpal ii, “king of the world, king of Assyria ... the mighty warrior … whose hand has conquered all lands.”

One of those conquered lands was the kingdom of Urartu, north of Assyria, in what is now eastern Turkey and Armenia. Famed for their metalwork, Urartians fashioned weapons, helmets and shields embellished with lion-headed serpents and sacred trees to ward off evil in general and their Assyrian foes in particular. Bashed, bent and ripped with gaping holes from spear thrusts, one magnificent, burnished shield on display illustrated an object lesson in defeat. “This is just a taste of what it must have been like to go to war against the Assyrians,” Aruz wrily observed as we regarded the crumpled armor.

|

| BRITISH MUSEUM |

| “A strange combination of violence and tenderness,” said curator Joan Aruz of this ninth- or eighth-century bce plaque of ivory, gold and semiprecious stones, shown here nearly slightly larger than life-size, from Nimrud’s Northwest Palace. Though Neo-Assyrian in origin, its style is Phoenician and its iconography draws from Egypt, where such images expressed royal authority over territory, here interpreted as Nubia due to the youth’s hairstyle. |

But it was the gruesome depiction of the battle of Til Tuba, in what is now southern Iran, that most forcefully drove home Assyia’s take-no-prisoners battle ethos. This wall-sized, almost panoramic relief, more than two meters high and nearly five-and-a-half wide, details more than a dozen brutal scenes: In one, the Elamite king Teumann and his eldest son are beheaded in front of one another, surrounded by a fray of upended chariots and carnage; in another, Assyrians force the Elamites’ Babylonian allies to their knees to grind the bones of their own ancestors in humiliation.

More tranquil scenes of daily life were not generally regarded as worth the effort of sculpture: War, hunting, invoking gods and monsters for apotropaic protection were the rule. That’s why the isolated domestic tableau showing a woman sitting on a chair, her feet daintily folded beneath her and proudly holding up a threaded spindle, seems so exceptional. Its realism and simple humanity impart a rare confidential glimpse into a private domain in the distant past. Tellingly, the bitumen relief sculpture is not Assyrian, but Elamite.

No less unusual and compelling is another ivory relief that stopped us in our tracks: It shows a Nubian boy being mauled by a lioness. “There’s such a strange combination of violence and tenderness, as the lioness cradles the boy’s head in her paw even as she is tearing out his throat with her teeth,” said Aruz. In spite of its grisly subject, there was an ineffable compassion toward the boy’s sacrifice, as if in it there lay some mystical meaning waiting to be decoded.

Among the largest items in the exhibit, two imposing basalt monoliths, from the Syro-Hittite site of Tell Halaf, attested to the persistence of a restoration team in Berlin that faced a mountain of nearly 30,000 archeological fragments, the remains of some 30 sculptures that shattered in a World War ii firebombing. The splinters had languished in the cellars of the Pergamon Museum for nearly six decades, East German officials having judged the works as irretrievably lost.

Among the largest items in the exhibit, two imposing basalt monoliths, from the Syro-Hittite site of Tell Halaf, attested to the persistence of a restoration team in Berlin that faced a mountain of nearly 30,000 archeological fragments, the remains of some 30 sculptures that shattered in a World War ii firebombing. The splinters had languished in the cellars of the Pergamon Museum for nearly six decades, East German officials having judged the works as irretrievably lost.

Optimistic experts from the reunified country, however, thought otherwise. It was, essentially, a series of giant, 3-D puzzles—less complicated no doubt than putting together the split German nation, but monumental nonetheless. Beginning in 2001 and finishing nine years later, the experts reassembled more than 30 sculptures. One scorpion-tailed bird man with a distinguished beard stood over a meter and a half tall, and he guarded the site’s Western Palace much like the better-known winged sentinels at Nineveh and the scorpion-men standing watch over the sunrise in the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh.

|

| STEFFEN SPITZNER / BPK / VORDERASIATISCHES MUSEUM, STAATLICHE MUSEEN ZU BERLIN / ART RESOURCE |

| One of some 30 Syro-Hittite sculptures that took nine years to reconstruct after a World War ii firebombing, this early ninth-century bce basalt statue of a scorpion-tailed bird man once stood beside the “Scorpion Gate” of a palace at Tell Halaf in northern Syria. |

Nearby was a distinctly less impressive chunk of basalt. A little larger than a hand span on each side, the rather ordinary-looking stele turned out to be a unique document of dramatic historical importance. Inscribed in Aramaic, the text recounted the conquests of the ninth-century bce Syrian king Hazael, and among them appears a royal descendant of the House of David. This is the sole known mention of the Davidic dynasty outside the Bible, the first archeological evidence of the historical existence of King David as the founder of Judah.

Among the show’s most delicate, hauntingly arresting works were Tridacna squamosa, or giant clam shells, as big across as a hand, incised with mind-blowingly detailed tableaux including miniature musicians, lotus buds, palm trees and—rather incredibly—men in kilts riding jauntily caparisoned horses. The hinged knob of one shell was carved to resemble the head of a woman, or perhaps the goddess Astarte, her long tresses morphing into feathers as they streamed down the shell back that undulates like waves. Another shell bore the incised head and face of a bird man at its top; swooping wings etched on the shell’s exterior protectively sheltered a pair of compact sphinxes. Tridacna clams thrive in the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea, and their shells were imported over vast distances to be engraved in Levantine workshops. From there, they were exported across the Near East and the Mediterranean as luxury containers for cosmetics.

The most publicized of the show’s curatorial coups involved, perhaps not surprisingly, gold. Aruz’s acquisition for loan from Seville of the seventh-century bce Carambolo treasure made front-page headlines in Spain. Weighing in at a stupendous 2.4 kilograms (5¼ lb), the solid gold necklace, bracelets and plaques were items worn by Phoenician priests who presided over ritual sacrifices of animals to the Phoenician deities Baal and Astarte by colonists of Spal, near what is now the modern city of Seville.

So valuable are these relics that the city’s archeological museum displays replicas, and the originals are kept in the vault of the national bank. When Aruz insisted that the Metropolitan would accept only the originals, the Spanish authorities took her to the vaults and made the New York show a rare occasion when the public was allowed to view them.

|

| STAATLICHE MUSEEN ZU BERLIN / VORDERASIATISCHES MUSEUM |

| One of roughly 575 protective and symbolic creatures that adorned victorious Babylon’s Ishtar Gate, built between 604 and 562 bce after the Babylonian conquest of the Neo-Assyrians, is a mushhushshu dragon, rendered in glazed and molded brick. |

Like any power, Neo-Assyrian domination did not forever endure. After bringing the Near East to heel for centuries, the once-invincible empire was fatally weakened in the mid-seventh century bce by a civil war between jointly ruling, rival brothers. One of them, Ashurbanipal, was portrayed in the show on a stone stele bearing a basket of earth on his head to symbolize his role in rebuilding Babylon after his grandfather Sennacherib had mercilessly sacked the city some two decades earlier. To his elder brother Shamash-shuma-ukin, named by their father as the king of Babylon, the inscription pledged fond wishes: “May his days be long and may he be fully satisfied with (his) good fortune.”

But after 16 years of sharing power, Shamash-shuma-ukin revolted against his brother. Ashurbanipal mounted a four-year siege of Babylon that produced a famine that drove the city’s inhabitants to cannibalism. The defeated brother immolated himself in the flames of his burning palace in 648 bce. Some 36 years later, in 612 bce, Ashurbanipal’s capital city of Nineveh was in turn sacked by vengeful Babylonians. The Neo-Assyrian empire gave way to Neo-Babylonian rulers. Not long after that, they too gave way, to Persians, who brought about yet another fall of Babylon in 539 bce.

Some 200 years later, armies under the command of a Macedonian warrior later dubbed Alexander the Great brought an unprecedented wave of Greek conquest that swept from west to east, reversing the flow of culture and exchange, setting the world stage for the rise of western classical cultures.

|

In addition to contributing regularly to AramcoWorld, Paris-based Richard Covington has written about culture, history and science for numerous publications. |

www.metmuseum.org