The Far East

Written by John Lawton

Written by John Lawton

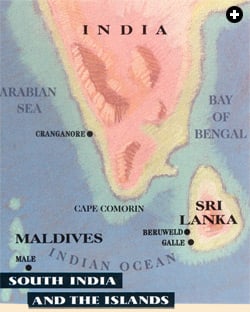

Although Islam's growth in Central Asia and northern India came in the wake of military expansion, its spread elsewhere in the East was largely marked by the absence of armed conquests. Carried by the sail rather than the sword, Islam first entered southern India when monsoon winds powered Arab dhows across the Arabian Sea to the subcontinent's west coast. Here in 664, tradition has it, two Muslim notables named Malik ibn Dinar and Sharaf ibn Malik landed at Cranganore with a party of learned men and their families, settled down and built India's first mosque.

More Muslims followed during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, founding trading colonies along India's western littoral, from Gujarat, in the More Muslims followed during the Umayyad north, to Cape Comorin, at the subcontinent's southern tip. From those settlements they exported black pepper, gemstones and textiles to Arabia, and imported incense and perfume.

More Muslims followed during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, founding trading colonies along India's western littoral, from Gujarat, in the More Muslims followed during the Umayyad north, to Cape Comorin, at the subcontinent's southern tip. From those settlements they exported black pepper, gemstones and textiles to Arabia, and imported incense and perfume.

The Hindu rajas of the coastal states left their Muslim subjects to worship as they wished - some even encouraged Islam - since the ruler's wealth and power depended almost entirely on customs revenues and profits from their personal transactions in maritime trade. Many coastal Hindus converted to the new religion.

The 13th-century conquest of Gujarat and Goa by the Sultan of Delhi further strengthened the position of Muslim merchants, who by then were sailing as far as Southeast Asia in search of silk, spices and other riches, taking their religion with them. Indeed, prominent Muslim merchants became commercial partners and political allies of local rulers in lands all along the trading routes, furthering the spread of Islam.

This was the case in Indonesia, where conversion to Islam began when Muslim merchants acquired a permanent foothold on the northern tip of Sumatra about 1290, and in Malaysia, where Malacca became a stronghold of the faith following a 1445 palace coup backed by Muslim merchants. .

|

| Built in 1560, Safa Shahouri Mosque at Ponda in Goa, was allowed to decay during Protuguese occupation, but has recently been restored. |

From Malacca, the main trading center of the region, Islam was disseminated along the trade routes northeast to Brunei and the Philippines, southeast to Java and the Spice Islands.

Preachers, religious teachers and devout Muslims followed in the merchants' wake, their teachings finding fertile ground among the people of the South Asian islands. Yet historians puzzle over why the new faith took root so easily in a region whose existing cultural tenor was so alien to Islam, which in its purest form is austere, demanding, egalitarian and uncompromisingly monotheistic.

One reason frequently given for Islam's acceptance is that it came as a social revolution that freed the common man from his Hindu feudal bondage - as it had in Pakistan and northern India. However, the evidence indicates that it was the old Hindu-Buddhist aristocracy which converted first. Another possibility is suggested by Muslims who say that Islam spread quickly because its basic teachings are easily grasped by the common man.

Certainly the commercial advantages which Muslims enjoyed at a time when Islam dominated the culture of the Indian Ocean trading system were not lost on some Southeast Asian island princes - nor was the political attraction of Islam as a counter to the threat of Portuguese and Dutch incursions. Yet few Asians adopted Christianity when Christian countries seized control of the spice trade; on the contrary, Islam became a rallying point against colonial domination

|

| The gold-capped minaret of Sultan Thakorotuan Mosque in Male, capital of the Maldives. |

Whatever the reason, it is clear that the teachings of the Qur'an were freely embraced by many of the peoples of South Asia. By the close of the 16th century most of the Hindu states of the region had been converted, the main exception being Bali, which never adopted Islam.

Arab traders also settled in Sri Lanka, and converted the Buddhist Maldive Islanders to Islam, which they still profess.

Following Islam's path east along the old Indian Ocean trading routes, Wheeler and I sailed into Male, capital and only town of the Maldive Islands, in a tropical storm. We huddled for shelter in the stern of a dhow ferrying merchandise among the 1196 palm-tree-covered, coral-reef-ringed islands -average size four square kilometers, or 1.5 square miles - which make up this remote republic.

But although today the Maldive atolls, drizzled across the equator like strings of pearls some 720 kilometers (450 miles) off the southern tip of India, have a "lost paradise" look, they once provided regular anchorage for ocean-going dhows engaged in international trade.

For not only were they strategically located along the Indian Ocean trading routes, but the Maldives also produced two commodities vital to East-West trade. One was coir, or coconut-fiber rope, used to stitch together the hulls of dhows - for dhows are sewn, not nailed, together. The other commodity was the shells of the little marine gastropod called the cowrie, which were used as currency as far east as Malaysia and as far west as the African Sudan.

The Maldive Islanders were originally Buddhist, but in 1163 their ruler became a Muslim and - as often happened in Southeast Asian states - his subjects followed suit. In his Rihlah - the account of his travels - 13th-century Muslim judge Ibn Battu-tah recounts the legend, told even today by old men of the islands, of Abu al-Barakat, a pious Berber from the Maghrib who rid the islands of a terrible demon by reading aloud the Qur'an. The ruler of the time, persuaded, then razed the Buddhist shrines and ordered the new faith to be propagated among his subjects.

From the Maldives, eastbound traders headed for Sri Lanka, which served as one of the main transhipment centers for goods moving between the two halves of the Indian Ocean. The normal pattern - at least until the early 15th century - was for lateen-rigged Arab dhows to carry goods across the western half, and Chinese junks, with their lug-type fore-and-aft sails, to carry them across the eastern half.

Almost all the transit trade of Sri Lanka and the southern Indian ports was in the hands of Muslims. Furthermore, owing to the Yuan Dynasty's policy of encouraging foreign participation in China's sea trade, even the owners and captains of junks, as well as the merchants who sailed in them, were more often than not Muslims of Indian, Arab or Persian descent. Muslims were thus masters of the early medieval East-West trade.

Arab traders gave Sri Lanka the name Sarandib, a name that Horace Walpole, in a fairy tale called "The Three Princes of Serendip," expanded into serendipity, or what the dictionary now calls "an aptitude for making desirable discoveries by accident." And indeed, it was only by happy accident that we found the mosque in the old walled port of Galle, on Sri Lanka's southern tip. With its twin-towered facade and oblong "nave," it resembled a church so much that we almost walked past it.

"Architects," explained a Muslim who lived opposite the mosque, "were more conversant with church architecture at the time it was built," during the occupation of the island by Western trading companies, whose steamships eventually displaced the dhow and the junk as giants of East-West trade.

|

| A focal point for Sri Lanka's Muslim minority, Kechemalai Mosque at beruweld marks the location of the first recorded Muslim settlement on the island in 1024. |

There was no mistaking, however, the domed and minaretted Kechemalai Mosque, built on a headland overlooking the fishing-boat-filled harbor of Beruweld, further up the coast. Today a focal visiting point for Sri Lanka's Muslim minority, the mosque is said to stand on the site of the first Muslim landing, and subsequent settlement, on Sri Lanka in 1024.

From Sri Lanka Islam followed trade across the eastern half of the Indian Ocean to northern Sumatra. And it was here, at Aceh, where the trade route from India and the West reached the Indonesian Archipelago, that Islam gained its first firm footing in the Far East.

Marco Polo, stopping off in Sumatra on his way home from China in 1292, reported that the coastal principality of Perlak was already Muslim "owing to contact with Saracen merchants, who continually resort here in their ships." And in 1332, when Ibn Battutah visited neighboring Samudra, he found it a sophisticated Muslim sultanate with international relations with India and China.

|

| A Malaysian boy wearing the black songkok headgear of many Southeast Asian Muslims. |

From Sumatra, Islam spread east at the beginning of the 14th century across the Straits of Malacca to the Malay Peninsula, where the earliest record of Islam is a stone tablet found half-buried in the bank of a river, near Kuala Berang, in 1932. Written in Arabic characters in the Malay language, it proclaims Islam to be the official religion of the local ruler, records Muslim laws relating to sexual behavior and false witness, and is dated 1323.

It was not until the next century, however, that Islam became the dominant faith of the Peninsula. In 1400 the Sumatran prince Parameswara, fleeing from the excesses of the Hindu Majapahit Empire, founded the town of Malacca on the Malaysian side of the straits to which it now gives its name. Local tradition credits Parameswara too with introducing Islam, revealed to him in a dream by the Prophet Muhammad. But historians say it was not until a palace revolution, backed by Indian Muslims, brought Sultari Muzaffar Shah (1445-1459) to the throne that Islam truly prevailed in Malacca. And it was during the reign of his successor, Man-sur Shah (1459-1477), who conquered all the peninsula up to the Burmese border, that the majority of Malays embraced Islam.

|

| The blue and white checkered dome of the Selangor state mosque appears through the soaring pillars of its main entrance. |

The conversion of Malacca, by then the greatest trading center in Southern Asia, gave Islam a powerful new base from which it was spread to the region's numerous port kingdoms, which were then freeing themselves from the slackening grip of the declining Majapahit Empire and other residual Hindu-Buddhist powers.

It was at this stage, however, that the Portuguese, attracted by the vast profits to be made from trade in spices and other Oriental luxuries, appeared in the Indian Ocean. Unable to break into the close-knit Islamic trading network, the Portuguese quickly resorted to force. They seized Malacca - the hub of this trade - in 1511 and scattered its Muslim merchants all over Southeast Asia, thus spreading Islam even further afield.

For centuries a city of pivotal importance in global trade, Malacca is now just a cog in minor coastal commerce. Scruffy little motor sailers carrying wood and charcoal from neighboring Sumatra have replaced the stately dhows, junks and galleons which brought gemstones, silks and perfumes from far lands. But the old red-tile-roofed town, clustered around Malacca's river-mouth harbor, still has a colorful, cosmopolitan flavor.

|

| Ocean-going Arab dhows once called in the Maldive Islands as they rode the monsoons across the Arabian Sea, but today only fishing boats ply the waters of the 1196-island republic. |

Austere colonial administrative buildings ring the main square, ornate Chinese merchants' residences line its narrow streets and Malay fishermen's homes huddle on stilts along the river bank.

On Harmony Street, Kampong Keling Mosque, with its typically Indonesian two-tier pyramidal roof and pagoda-like minaret, stands between a shrine dedicated to the Hindu deity Vinayagar and a Chinese temple combining the doctrinal beliefs of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism. On a hilltop overlooking the harbor stands the ruined church of St. Paul and a statue of the indefatigable Catholic missionary Francis Xavier, said to have traveled 60,000 kilometers (38,000 miles) across Southeast Asia.

More typical, however, of today's thriving Muslim Malaysia are the towering skyscraper offices and hotels of Kuala Lumpur. Midway between the federal capital and modern Port Klang stands the Selangor state mosque, whose distinctive dome and soaring 142-meter (455-foot) minarets gave us our last glimpse of Malaysia as we jetted across the Straits of Malacca to Sumatra.

|

| The threetop-level onion domes and ornate minarets of Jakarta's Jami'Masjid contrast sharply with the city's hard-edged skyscrapers. |

For, after conquering Malacca, the Portuguese attempted to extend their influence to the Muslim port-states of Sumatra. The effect, however, was to unite them under the banner of Aceh, a new sultanate formed around 1500 at the northwestern tip of the island. Aceh then entered a period of great prosperity, replacing Malacca as the center of the region's Muslim trade network and as the regional stronghold of Islam.

Aceh's peak of power and wealth was reached under Sultan Iskandar Muda (1607-1636); his palace, glittering with gold, aroused widespread admiration - as did the great five-story mosque at Banda Aceh, the sultanate's opulent capital. But warfare and the impermanence of wooden buildings have left little trace of either, except for a strange stone structure - resembling tombstones piled against a central pillar - which architects cannot decipher: It appears to be either a scientific observatory or a sultan's folly.

|

| This large gong - a reminder of Southeast Asia's pre-Islamic past - is used to accompany the standard Muslim call to prayer at the Masjid Agung in Demak, once the capital of Java's first Islamic kingdom. |

An imposing five-domed mosque, however, still dominates the center of Banda Aceh - one built not by Muslims, but by the Christian Dutch, in 1897, to replace the mosque they destroyed during their assault on the sultanate to seize control of its pepper trade. But the mosque, modeled on a mixture of styles from Arabia, India and Malaysia, failed to appease the Acehnese, who fought a bitter 40-year guerilla war against Dutch occupation.

Islam's next destination east - and ours also -was Java, the most populous of the 13,677 islands of the Indonesian Archipelago, where it is believed that it was among the Chinese minority that the new faith found its first adherents.

In the 15th century, records show, the scribe Raden Rahmat was appointed by the Majapahit court to be imam of Ngampel Denta, the foreign quarter of Surabaya at the eastern end of Java, and his numerous pupils spread Islam across the island. The faith received an important boost when coastal princes of north Java, who had grown tired of subservience to the Majapahit Hindu god-king, broke their ties with him by embracing Islam. The most prominent of these new independent Muslim kingdoms was Demak, which became Java's first Islamic state, conquering and converting the whole northern coast between 1505 and 1546, and snuffing out tfcie last remnants of the Majapahit Empire in the process. Today Demak's Masjid Agung, said to have been built in 1428, is Java's oldest and most revered mosque. Tradition has it that four of the carved pillars supporting its deeply recessed veranda were brought from the Majapahit court following its fall in 1518. Certainly they are old - as are the four other massive wooden pillars that underpin the mosque's three-tiered pyramidal roof - although the remainder of the building was completely rebuilt in 1845 and again in 1987.

Still more interesting is the mosque of nearby Kudus, for not only are its split gates reminiscent of those of a Balinese temple, but its red-brick minaret is so similar to a Hindu kulkul, or gong tower, that it may actually have been one. Kudus is a corruption of al-Qiids, the Arabic name for Jerusalem, and the town is one of the few in Java with an Arabic name. The mosque itself is known as al-Aqsa. It was founded in 1549 by Sunan Kudus, one of the nine teachers popularly credited with the Islam-ization of Java, and his carved tomb at the rear of the mosque is today an important site among Javanese Muslims.

|

| Light filters through stained glass windows to reveal the elegant Moroccan-style interior of Masjid Raya, the largest mosque in Sumatra. |

Muslim forces broke Hindu control of Sunda Kelapa, in west Java, on June 22,1527 - a date still celebrated - and renamed it Jakarta, or City of Victory. It is today the capital of Indonesia.

Traveling on eastward along the trade routes beyond Java to other islands of the Indonesian archipelago, Islam then spread to the Spice Islands of Ternate, Ti-dore, Banda and Abon -part of the group called the Moluccas - in the latter half of the 15th century, and to Sulawesi in 1605, finally reaching New Guinea in the 17th century, where today a sprinkling of coastal Malays represent Islam's easternmost penetration.

Despite the passage of centuries during which Arab merchants had sailed to the Moluccas to trade cloth and luxuries for nutmeg, cloves and cinnamon, the Spice Islanders were among the last Indonesians to embrace Islam. Local tradition credits their conversion to the artful Javanese missionary Mawlana Husayn who found the Moluccans fascinated by the mysterious shape of the Arabic script in which the Qur'an is written and vainly trying to imitate it. He offered to teach them to read and write Arabic - but only those who accepted Islam would be allowed to learn the sacred letters. In this way Husayn won many converts.

The first Muslim ruler of Ternate was Zayn al-'Abidin (1486-1500), who took the title of sultan; his descendants still use the honorific today, a rare privilege in the modern Indonesian republic. Sultan Zayn is credited by Abon historian Rijali with converting Perdana (prince) Jamilui, the ruler of Hitu, one of Abon's two peninsulas, whose people fought a fierce struggle with the Portuguese when, in 1574, the Europeans established themselves on Lestmor, Abon's still-heathen peninsula, and introduced Christianity. To ensure communal harmony today, the Abonese practice a system whereby each village is paired with another of a different faith, with villagers attending each other's religious festivals and even helping to build or repair each other's churches or mosques.

|

| Plants reclaim the ruins of a subterranean mosque in the Tamar Sari, a park built by the first Muslim sultan of Yogyakarta. The city was the royal - and the remains of the cultural - capital of Java. |

Because of remarkably detailed accounts by 17th-century Makassar historians, there is more information about the conversion to Islam of Sulawesi - formerly known as the Celebes - than that of any other Indonesian island. These chronicles, for example, give the exact date - September 22, 1605 - that the ruler of Makassar, the southernmost of the four tentacle-like arms of Sulawesi, accepted Islam. According to the same accounts, this event followed long years of contact with Muslim merchants, and was followed, on November 19, 1607, by the first Friday prayers in Makassar, at which those who had not already done so publicly professed Islam.

From then on, the people of Makassar became champions of Islam in East Indonesia, playing an important part in the battle between the Dutch and the Muslims of the Moluccas for monopoly of the spice trade. And although the Dutch won the trade war, their missionary efforts on behalf of Christianity were as unsuccessful as those of the Portuguese had been elsewhere in Indonesia, where Francis Xavier and others succeeded only in converting those remote islands - sugh as Flores and Timor -which Islam had not already reached.

As a result, Indonesia today has the world's largest Muslim population.

The rise of Islam in Indonesia heralded no great artistic renaissance like that in India under the Moguls. But, stimulated by the sultans of the new Javanese Islamic states, the textile decorating art of batik flourished, while xvayang puppetry and game-Ian music attained their most refined and subtle development.

|

| Because the Moluccas - Indonesia's Spice Islands - experience frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, many buildings, including this mosque at Abon, are built of light tin sheeting. |

Borneo - the third largest island in the world after Greenland and New Guinea - received Islam from three different directions. From Sulawesi, in the east, Dato'ri Bandang and his followers spread Islam to Kutai state - now a major oil- and gas-producing region - on the eastern coast of Borneo. The state of Banjarmasin, in southern Borneo, was converted from Java to the south, and chronicles record a conflict between two pretenders, Samudra and Tumengung, in which the former enlisted the aid of the Muslim rulers of Demak, who dispatched 1000 warriors to Banjarmasin to settle the dispute in Samudra's favor and convert his sub-jects to Islam.

Brunei, on the northwestern coast of Borneo, along with the Sulu Islands and the southern Philippines, was situated on a trade route which linked Malacca and China, and it is mostly Arabs, calling in on their merchant travels, who are reputed to have been the bearers of Islam to these three regions. An Arab, Sharif Karim al-Makhdum, is said to have settled in Ewansa, in the Sulu Islands, where the people built him a mosque, flocked to it and were converted. Sharif Kabungsuwan, a native of Johor Baharu and son of an Arab father and Malay mother, is said to have spread Islam in the southern Philippines until the Spaniards established themselves in the north and prevented it from penetrating any farther.

According to the genealogy of the Sultans of Brunei, Sultan Muhammad Shah was the first ruler to establish a Muslim kingdom in Brunei in 1386; local legend says he embraced Islam after marrying Puteri Johor, daughter of the Muslim king of Tema-sik - present-day Singapore - in the early 1360's. But some Muslim scholars believe a Muslim kingdom existed in Brunei as early as 1301, and that Islam was introduced to the sultanate from China.

|

| Ternate's inhabitants traded nutmeg, cloves and cinnamon with Arab merchants for centuries, but embraced Islam only at the end of the 15th century. |

As evidence of this, they point to the tombstone of Maharaja Bruni, found in Brunei and inscribed in Arabic rather than in Jawi, the Malay language, written in Arabic script, used on other royal Brunei tombstones. Although the stone gives neither the personal name nor the date of the Maharaja Bruni, it has been identified by comparative methods as having been engraved in Quanzhou, China, about 1310 and then transported to Brunei. Chen Da-sheng of China's Fujian Academy of Social Sciences, and author of Islamic Inscriptions in Quanzhou, says the tombstone is identical in material, design, carving, wording and spelling to that of Fatima bint Naina Ahmad, who died in Quanzhou on May 22, 1301, and it was almost certainly made by the same craftsmen.

How, then, did Islam reach China?

It came from two different directions: from the northwest along the overland caravan routes across Central Asia, and from the southeast through the ancient trading ports on the South China Sea. And the geographical distribution of Muslims in China today still reflects these two main routes of penetration.

The majority of China's 16 million Muslims are Turkic peoples living in the vast Xinjiang region of northwest China. The rest are mainly Hui - either descendants of Chinese converts to Islam or the offspring of Chinese intermarriages with Muslim immigrants - whose appearance is distinctly Chinese. They live in sizeable communities in the former Silk Road oases of western and central China, in the southern province of Yunnan, and in the industrial cities and ports of the east.

|

| Two of Islam's main entry points into China were the Pearl River port of Guangzhou in the southeast and the northwestern oasis of kashgar, site of Central Asia's largest weekly open-air market. |

Contacts between Muslims and Chinese began very early. Arab merchants traded in silk even before the advent of Islam, and tradition has it that the new religion was brought to their port-city trading colonies by Muslim missionaries in the seventh century.

In 755, a contingent of 4000 soldiers, mostly Muslim Turks, was sent by the Abbasid caliph Abu Ja'far al-Mansur to help the Chinese emperor Su Tsung quell a revolt by one of his military commanders, An Lu-Shan. Following the recapture of the imperial capital, Ch'ang-an (today's Xian), these soldiers settled in China, married Chinese wives and founded inland Muslim colonies similar to those established by the traders on the coast.

Islam made its first real inroads into what is now western China in the middle of the 10th century, with the conversion of Sultan Sutuq Bughrakhan of Kashgar and his subsequent conquest of the Silk Road oases of Yarkand and Khotan in southwest Xinjiang.

|

| Two of Islam's main entry points into China were the Pearl River port of Guangzhou in the southeast and the northwestern oasis of kashgar, site of Central Asia's largest weekly open-air market. |

During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), China experienced spectacular economic growth. This stimulated expansion of the Muslim mercantile communities - particularly in Ch'ang-an, the eastern terminus of the Silk Roads, and in the port cities of Quanzhou and Guangzhou, where Muslims largely governed the internal affairs of their own neighborhoods, building mosques and appointing qadis to adjudicate according to Islamic law.

But although some Chinese merchants involved in international trade did become Muslims, other converts were few, and Islam in China was confined largely to Muslim immigrants and their descendants. Until, that is, the Mongol invasion overthrew the Song Dynasty and ushered in what Chinese Muslims regard as the "golden age" of Islam in China.

|

| Inscriptions on Muslim tombstones like this one, at Guangzhou in China, have helped scholars piece together the early history of Islam in Southeast Asia. |

Although the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1260-1382), founded by Kublai Khan, was the only one of the four great Mongol khanates whose rulers never converted to Islam, they nevertheless gave Muslims special status, often placing individual believers in responsible, even powerful, positions of state. In addition, when Yunnan fell to the Mongol invaders and most of its population fled, leaving an empty land, Kublai Khan sent the tough Muslim soldiers from Central Asia who had helped him conquer China to repopulate the south - though this was probably partly to keep them out of mischief and far from his own capital. It was also during the Mongol period that the Uighur Turks of northwestern China converted to Islam.

Following the conversion of the Chaghatai Mongols of Central Asia in the 13th century, large stretches of northwest Xinjiang were won over to Islam. In 1513 the oasis of Hami in eastern Xinjiang put itself under the sovereignty of Mansur Chaghatai, who two years later made it his capital and a base from which to spread Islam even further east. The religion advanced as far as Lanzhou, in today's Gansu province, where a Muslim seminary still operates on the banks of the Yellow River.

When the indigenous Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) overthrew the Mongols in their turn, however, the Muslims' position began to deteriorate. They lost their special status and under the Ch'ing, or Man-chu, Dynasty (1644-1911) were so oppressed that they rebelled repeatedly - most notably in the Panthay Rebellion, which lasted from 1855 to 1873, but was crushed with great cruelty.

Because of such repression, the Hui Muslims developed a strong sense of community, living in segregated enclaves usually focused on a single mosque. The roofs of their prayer halls flared, Buddhist-style, and their minarets were built like squat pagodas so as to blend with neighboring Chinese architecture. Mosques in the predominantly Uighur northwest maintained the traditional Muslim architectural style of domed roof and tall, slender minarets, however.

In the 20th century, Muslims throughout China continued to practice their faith discreetly following the advent of Communism, despite the ideology's atheistic principles. But during the savagery and purges of the Cultural Revolution, between 1966 and 1971, most mosques were destroyed or closed down. Then, following the death of Mao Zedong, Muslims were again given a limited amount of religious freedom. Mosques and religious schools were reopened and some hundreds of Muslims were permitted to make the pilgrimage to Makkah.

And when I visited China in 1984 with Nik Wheeler, to write and photograph a special issue of Aramco World on the country's Muslims, and again in 1987 with photographer Tor Eigeland to research another issue, on the Silk Roads, we found China's renovated mosques crowded and the call to prayer echoing once more from the minarets of the northwestern province.

|

| Huaisheng Mosque couryard. |

In Beijing, also, we saw the recently repainted Niu Jie mosque, its pillars lacquered in red and gold and its walls covered with a mixture of Arab and Chinese motifs. In Xian we watchtd workmen restoring the Great Mosque - China's largest - said to have been built by the 15th-century Muslim hero Cheng Ho, who cleared the South China Sea of pirates and rose to be admiral of the emperor's fleet.

|

| Grand Mosque in Xian has the elaborately flared eaves typical of Chinese pagodas. |

|

| The minaret of Huaisheng Mosque in Guangzhou is simple and smoothly finished like traditional buildings of Arabia. |

In Xinjiang we found that, despite government attempts to dilute the Muslim population by settling masses of Han Chinese among them, the region still retains a distinct Muslim atmosphere. Here the men wear gaily embroidered skullcaps and go regularly to the mosque to pray. They also proudly tell visitors that Wuer Kaixi, who headed the 1989 democracy movement that culminated in Beijing's Tiananmen Square, was a Uighur from Xinjiang.

Policies introduced by the Chinese government since then, limiting Muslim families to two children per couple in urban areas and three to four in rural areas, along with curbs on religious education, have caused new friction between the Uighurs and the Han Chinese. In the Xinjiang village of Baren last May, for example, 22 people died in clashes with security forces following Beijing's denial of permission to build a mosque.

There was no sign of friction, however, when we arrived in Quanzhou, this year, on the last leg of our journey along Islam's path east. In fact, Hui Muslims played a prominent part in official ceremonies welcoming the UNESCO Silk Roads survey ship Fulk al-Salamah, which Wheeler and I had rejoined in Guangzhou, known in the West as Canton.

Over 2400 kilometers (1500 miles) from Beijing and only a short train ride from Hong Kong, Guangzhou has always been more open to foreign influence than other Chinese cities, and its mosque is generally considered to be the oldest in China. Said to have been founded by one of the first Muslim missionaries to China some 1300 years ago, Huaisheng Mosque displays a mixture of architectural styles: a 36-meter (118-foot) cone-shaped minaret, built during the Tang Dynasty (618-906), towers over a cloistered courtyard and the sweeping tiled roofs of the prayer hall, rebuilt to replace the original that was destroyed by fire in 1343. It is also known as the Beacon Tower mosque, because during the Tang and Sung Dynasties, when the Pearl River flowed close to the minaret - before silting shifted it away - a light was hung at night from the top of the tower for navigational purposes.

|

| A Muslim member of the party that welcomed Lawton and Wheeler to Quanzhou at the end of their retracing of Islam's path east. |

We sailed down the Pearl River estuary and out into the South China Sea, running into thick fog and then heavy rain as we approached Quanzhou. But it failed to dampen the spirited reception for the Fulk al-Salamah: massed bands, lion dancers, acrobats - and Hui Muslims - gathered jubilantly at dockside.

Once one of the world's largest ports, Quanzhou reached the peak of its prosperity during the Sung Dynasty's commercial revolution, with Muslim merchants playing a leading role. Today, however, the bustle of big-time commerce has gone, leaving the city a rich cultural heritage of classical Chinese buildings and an opera unchanged in song, dance and music since the Ming era.

Of the city's mosques, which once numbered seven, only one remains. But the massive granite walls of Masjid al-Ashab, built in 1009 in this, one of Islam's easternmost outposts, reflect the enduring vitality of a faith born in the deserts of Arabia and spread across Central Asia and India, all the way to China's Pacific shores.

And that is only its diffusion in one direction: eastward. Islam's way west is another story.

|

Aramco World contributing editor John Lawton has eight other complete issues of the magazine to his credit, the first published in 1977. He is also the author of Samarkand and Mukhara, published in London by Tauris Parke Books. |

This article appeared on pages 50-68 of the November/December 1991 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

See Also: BRUNEI, CHINA, INDONESIA, ISLAM—BRUNEI, ISLAM—CHINA, ISLAM—FAR EAST, ISLAM—HISTORY, ISLAM—INDONESIA, ISLAM—KOREA, ISLAM—MALAYSIA, TRADE

Check the Public Affairs Digital Image Archive for November/December 1991 images.