Journeys of Faith, Roads of Civilization

Written by David W. Tschanz

Roped four abreast, the column of camels shuffled in the darkness across the rocky plain, each following the shadowy forms of the four in front. The drivers and passengers intermittently dozed in the saddle, then jerked awake, then dozed again. From a distance the sweeping train was marked by the swaying of lanterns and the faint accompaniment of tambourines.

In the east the sky lightened, marking the caravan's 40th morning, now in a landscape shaped by volcanic upheavals. As the sun rose, so did the temperature. Camels gurgled, brayed, balked and strode on, as tired as the pilgrims riding them and the hardy ones on foot, all stolidly going on at the insistent command of the caravan leaders.

It was a sharp-eyed camel boy at the head of the column who first spotted the tiny smudge on the horizon, appearing, then disappearing in the shimmering light. Pushing toward it, the caravan moved onto the floor of a small valley, then forced its way up a steep ridge and stopped. Everyone looked, their gazes awash with emotion born of a lifetime of faith and months, even years, of travel. In the valley of Abraham not far off, its whitewashed houses glistening in a little island of green, was the realization of the pilgrims' extraordinary exertions: Makkah, the City of God.

The Hajj, as the pilgrimage to Makkah is called in Arabic, is the fifth and final pillar of Islam. Performing it at least once is required of every Muslim who is able. A deeply spiritual event, it underscores the historical continuity of Islam's 14 centuries. By returning to pray at the site of the Ka'bah, and by commemorating in the rites of the ‘Id al-Adha Abraham's willingness to sacrifice his son at God's command, Muslims annually reinforce the links that bind them to each other, to the Prophet Muhammad and to the beginnings of monotheism.

|

|

| |

|

From Islam's earliest years in the seventh century, the desire to perform the Hajj set large numbers of people traveling to Makkah, the heart of Islam, and to Madinah, the city where the first Muslim community formed and where the Prophet Muhammad is buried. As a result, certain existing trade roads took on new importance and new routes developed that crisscrossed the Muslim world. To ease the pilgrims' journey, and for the sake of reward in the hereafter, rulers and wealthy patrons built caravanserais, supplied water and provided protection along these roads to Makkah and Madinah. Individual Muslims, in the name of charity, helped others to make the journey, and giving to poor pilgrims was considered a pious act.

So beyond what each pilgrim's Hajj meant to him or her spiritually, the Hajj took on great importance as a social phenomenon, contributing enormously to forging a melded Islamic culture and a worldwide Islamic community whose shared characteristics bridged differences of nationality, ethnicity and custom.

Over the centuries, the padding of human and animal feet and the muffled sounds of their caravans were heard through every valley, village and mosque from the Atlantic shores of Africa and the Iberian Peninsula to the Pacific coast of China, from Zanzibar in the south to the Caucasus and Central Asia in the north. The stream of pilgrims passed even the most out-of-the-way corner of the Dar al-Islam (the Islamic world), and everywhere everyone knew someone who had been on the Hajj. Each passing pilgrim was a tangible reminder of the scope of the faith and the reach of the culture.

|

|

| |

Paintings by one or more anonymous artists appear in The Maqamat (The Assemblies) of al-Hariri, a collection of stories and poetry that the author wrote in Baghdad near the beginning of the 12th century. It was recopied many times, and the paintings date from the early 13th century. Above, a group of pilgrims sets off toward the Holy Cities. (Photos12 / Bibliothèque Nationale De France.) |

| |

|

Hajj was the heartbeat of the Earth's first genuinely transcontinental culture. The Dar al-Islam, for nearly a millennium, was a composite Afro-Eurasian free-trade zone through which not only pilgrims but also traders, merchants and bureaucrats traveled with relative freedom and ease. By creating and nurturing this commons, the Hajj expanded the possibilities of science, commerce, politics and religion.

Pilgrims quickly discovered that, within the vast network of the Hajj, they were never really outsiders. Music, dress and accent could change a dozen times between Tangier and Delhi or between Samarkand and Makkah, yet the calendar, etiquette and much of human behavior remained almost identical. Everywhere Muslims prayed five times at the same times each day facing Makkah, everywhere they fasted together during Ramadan, everywhere they joined the pilgrims in sacrificing an animal at the end of the Hajj rituals, everywhere they practiced hospitality, and everywhere they drew their laws from the Qur'an. Commerce was supported by the system of caravan and sea routes. The closer one got to Makkah, the more the Hajj roads were the main arteries of this system, swelling with pilgrims from all points of the compass. No traveler came to the Holy Cities empty-handed, for some carried goods to pay their way, others bore local news that they carried among the provinces, and more learned ones brought the latest concepts and ideas, essential nutrients for the intellectual life of the Dar al-Islam.

|

|

| |

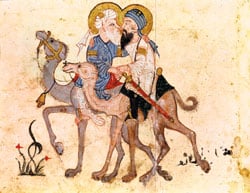

Two of The Maqamat’s characters, al-Harith and the narrator and traveler Abu Zayd, bid each other farewell before the pilgrimage. (Art Resource / Erich Lessing / Bibliothèque Nationale De France, MS. ARABE 58747, FOL.22.) |

| |

|

The Hajj likewise affected many who were not on the road. The desire to assist the pilgrim's orientation, observation and movements spurred Muslim advances in mathematics, optics, astronomy, navigation, transportation, geography, education, medicine, finance, culture and even politics. The constant flow of pilgrims turned the trails into channels of cultural and intellectual ferment.

To go on the Hajj during the first 13 centuries of Islam required far more than booking a flight through a travel agent. It was an extraordinarily long and difficult marathon across often unforgiving terrain, and an individual's travel could take years or even decades if he had to stop en route to work and save before setting out again. The land routes were often littered with the remains of caravans ravaged by raiding tribes, stricken by disease, short of water or just plain lost, and every seafaring pilgrim knew that the sea had swallowed many a boat. The risks often taxed pilgrims to their limits, but this did little to inhibit the remarkably steady flow of the Hajj. It outlasted empires and persisted through war, famines and plagues. The journeys of the past inspired Muslims for centuries and provided images and experiences of real sacrifice, absolute faith and exaltation. The Hajj—or more precisely, the pilgrims, the caravans and the routes that comprised it—became the glue binding together the whole of Islamic civilization. The journey to Makkah has always been more than just the destination.

|

|

| |

An old man and a young man of modest means take their rest in front of the fine tents of wealthy pilgrims. (Art Resource / Giraudon / Institute of Oriental Studies, St. Petersburg, MS. C-23, FOL. 438.)

|

| |

|

Caravan travel is probably as old as civilization. Most pilgrims experienced two segments of it, the first, the journey between home and one of the three great marshaling points at Baghdad, Cairo or Damascus. From there, the second segment was the formal, annual Hajj caravan to Makkah.

To reach the marshaling points, some came by boat, braving the waters of the Red, Black, Mediterranean or Arabian Seas, as well as the Arabian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. The vast majority, however, spent months slowly crossing great tracts of land. Pilgrimage from lands such as Indonesia or Morocco could entail round-trip journeys of 16,000 kilometers (10,000 mi) or more. In the 14th century, it took Ibn Battuta nine months to traverse just the northern coast of Africa, from Tangier to Cairo.

Some part of the distance and duration was by design. Some outlying Hajj roads do not follow the shortest distance between two points, but were intended to allow the pilgrim to visit mosques and holy places along the way to Makkah. For the pilgrim, the Hajj was not merely a religious duty, but also a process of personal renewal and growth.

Pilgrims carried the provisions they needed. The inbound caravans were well-supplied if the person traveling were rich, but the poor often ran short, and they often interrupted their journeys to work, save up their earnings and continue.

Pilgrims carried the provisions they needed. The inbound caravans were well-supplied if the person traveling were rich, but the poor often ran short, and they often interrupted their journeys to work, save up their earnings and continue.

Until about 1930, when King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa‘ud brought the tribes of Arabia under one flag, the pilgrims' danger was greater the nearer they came to the Holy Cities. The climate was harshest in the Hijaz, where water was at its scarcest and banditry by tribes who made a living on caravans of all sorts was at its most rampant. Together, these factors made joining one of the major caravans a virtual necessity, and protecting those caravans became a major responsibility of the ruling power of the time. Failure to assure the security of the Hajj caravan was seen as a tacit abdication of political legitimacy.

Although some pilgrims always came to Makkah by sea, through the port of Jiddah, their numbers were far less significant than overland travelers' until the 19th century. Likewise, while there were also northbound caravans from Yemen, their numbers too paled by comparison with the great caravans from Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad.

How many people made the Hajj each year? Reliable numbers are hard to come by, but the best estimates suggest that some 40,000 persons attended each year until the coming of steamship, rail and air travel. The size of a major Hajj caravan was typically reported by a variety of sources as numbering between 5000 and 8000 pilgrims, a number that gradually grew toward 10,000 by the end of the 19th century. In addition there were an unspecified number of merchants, soldiers, officials and others who took advantage of the relative security of the Hajj caravan to travel to and from the Hijaz and the ports of the Red Sea. Each caravan thus required about 25,000 to 30,000 camels, which had to be gathered each year outside Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad. The supply of these camels was a key economic and logistical factor both for the state, which operated the caravan and its support system, and for the individual pilgrims.

Each person was responsible for paying for his animal, supplies and expenses. Poorer pilgrims were often given their mounts and were assisted with expenses either by the government or as an act of charity by another person. The total cost was substantial. Official Ottoman registers from 1750 show that the fee from Damascus to Makkah was 70 piasters: 40 for food and transport; five for a place in the two-sided litter atop the camel; 15 for luggage (there was a weight allowance of 57 kilograms [126 lbs]); five for water; and five for the camel driver. The return trip cost 110 piasters because of the greater weight of goods being brought back and the consequently greater danger of attack. To put the cost in perspective, the annual salary of the imam of Damascus 's Great Mosque was 20 piasters, and 200 piasters was more than enough to buy an average-sized house in that city.

|

|

| |

At a rest stop along the route, pilgrims sleep in tents, care for their mounts and arrange their gear. (Bridgeman Art Library / Institute of Oriental Studies, St. Petersburg, MS. C-23, FOL. 12A.)

|

| |

|

The Ottoman terke defteri, which catalogued the possessions of pilgrims who had died en route, shows that most pilgrims traveled simply. One typical example is Mehmet A×ga, a Cretan landowner who died on the 1705 caravan. His possessions included a fur-lined cloak (his most expensive article of clothing), two other outer wraps, two shirts, a pair of boots, a coverlet and a napkin. His other equipment consisted of a small basin, four platters, two plates and a drinking cup. He also carried with him a kind of cardboard desk, writing implements and a basket.

The caravans were highly organized, and social historians note that their logistical feats indicate a high degree of sophistication from the earliest times. An annually appointed leader, the amir al-hajj—in some instances the caliph himself or a governor—oversaw a collection of high officials, who in turn governed a complex, mobile pilgrim-service industry of cameleers, medics, water carriers, torchbearers, cooks, scouts, guides and soldiers. Those who worked the caravans often did so year-round: Preparations would take six to eight months, with another three months being devoted to the round trip.

|

|

| |

Travelers rest in a caravanserai, traditionally designed with a large courtyard for stock and equipment overlooked by an arcade, off which lay small bedrooms. (Photos12 / Bibliothèque Nationale De France.)

|

| |

|

The amir al-hajj set the order of march and, en route, his word was absolute. No one could change position or drop out without his permission.

In accordance with the Qur'anic recommendation, the caravan typically departed on a Friday immediately after the noon prayer. By tradition, it was preceded by an unladen donkey, either for luck or for guidance. The camels were roped head-to-tail in strings of about 50, and the lead camel was decorated with parti-colored trappings, tassels and bells. Normally one third of the soldiers preceded the column, another third rode in the middle and the final third served as the rear guard.

The first day's march, being mostly a shakedown, typically did little more than clear the starting point and get below the horizon. Travel times differed slightly by season and terrain, but normally each day's travel was broken into sections. The first marching sequence ran from about two or three A.M. to ten A.M., followed by a rest period lasting until two or three P.M. The second march ran until about seven or eight P.M., followed by a rest until two A.M. This meant about 12 hours of travel each day, at a speed a bit more than three kilometers per hour (about 2 mph). The caravan arranged for several rest stops of two to four days' duration at prearranged locations where abundant water was available. While the caravan was on its way, the five daily prayers were often combined and performed at times that best coincided with the regular and necessary halts, a practice authorized by Muslim tradition.

Despite the sacred nature of the journey and the increased safety and security of a large caravan, each pilgrim needed nonetheless to have his wits about him. These were still mortal affairs rife with risk. Ibn Jubayr, laconic but observant, wrote in 1183 or 1184 of the “many hells that strew the road to Makkah.” Some pilgrims perished along the way—it has long been considered a blessing to pass from this life while undertaking the Hajj—and some undertook the journey knowing that death, from disease or old age, was imminent. Others died in less timely ways, from exposure, thirst, flash flood, disease or attack. In 1361, 100 Syrian pilgrims died of cold, and in 1430 some 3000 Egyptians died of heat and thirst. In 1757 virtually the entire Damascus caravan was lost to attack by raiders, a failure of state protection that cost the Ottoman governor of Damascus not only his office but his life.

Despite the sacred nature of the journey and the increased safety and security of a large caravan, each pilgrim needed nonetheless to have his wits about him. These were still mortal affairs rife with risk. Ibn Jubayr, laconic but observant, wrote in 1183 or 1184 of the “many hells that strew the road to Makkah.” Some pilgrims perished along the way—it has long been considered a blessing to pass from this life while undertaking the Hajj—and some undertook the journey knowing that death, from disease or old age, was imminent. Others died in less timely ways, from exposure, thirst, flash flood, disease or attack. In 1361, 100 Syrian pilgrims died of cold, and in 1430 some 3000 Egyptians died of heat and thirst. In 1757 virtually the entire Damascus caravan was lost to attack by raiders, a failure of state protection that cost the Ottoman governor of Damascus not only his office but his life.

The soldiers who accompanied the caravans were useless against the elements and disease, but they served as a deterrent to marauders who waited along the roads. The raiders were no quaint medieval threat: As recently as World War I, the lion's share of subsidies from Istanbul and London went to buying off the more predatory tribes in order to keep the land routes open for commerce and faith. Protection of the caravans was a major concern of the Ottomans, who became responsible for both the Egyptian and the Syrian caravans after taking Egypt from the Mamluks in 1517. In budgetary terms, protection of the Hajj caravans was equivalent to waging a large annual war.

While troops reduced the threat of raids, pilgrims were not immune to other forms of extortion, legal and otherwise. To everyone along the way, pilgrims were a potential source of income: To rulers, they were occasionally special taxpayers; to the keepers of city gates or bridges, they were toll payers; and to every entrepreneur and merchant along the way, they were potential customers. While direct taxes on pilgrims were generally illegal, taxes on their possessions or their camels were not, and in the towns merchants and shopkeepers increased their prices for items in demand by pilgrims, creating one more hazard of the road.

|

|

| |

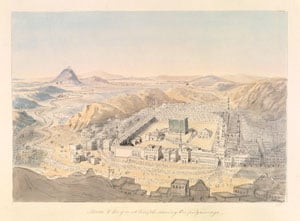

A view of Makkah in the early 19th century by Charles Hamilton Smith, an English officer and artist who is not known to have visited the Arabian Peninsula and who thus probably drew this from other sources. (Art Resource / Charles Hamilton Smith / Victoria and Albert Museum, London.)

|

| |

|

This was the commercial side of the Hajj, which economically was a kind of annual fair and transcontinental merchandising opportunity. Ever candid, Ibn Jubayr observed, “Not all go to Makkah out of devotion, and there are a number of people who make the pilgrimage only from hope for gain.” Others fell somewhere in between, for it was common for a pilgrim to partially finance his Hajj expenses by becoming a trader along the way. On the roads, in the ports and in the Holy Cities there was always something to buy and sell.

The merchants of Damascus and particularly Cairo used the relative security of the Hajj caravans not only to sell at retail to the pilgrims, but also to transport funds and goods wholesale to Makkah. Additionally, the merchants would meet in the Red Sea ports with agents from India, China, Southeast Asia and elsewhere. The caravans would bring European textiles, foodstuffs and a notable amount of coinage and return laden with spices, drugs, coffee and Indian textiles. Returning pilgrims were often weighed down with various objects of piety such as prayer beads, often in such large quantities as to suggest the intention of resale to the folks back home.

This all affected culture. A Tajik from Central Asia, for instance, might bring a rug to sell in Makkah, which might be bought by a North African pilgrim and transported back to Morocco. There, weavers could inspect and perhaps copy the workmanship and design of a craftsman thousands of miles away. Styles and techniques in art forms as diverse as leatherworking, calligraphy and ceramics were similarly disseminated along the routes of the Hajj.

Religious, scientific and literary manuscripts similarly changed hands along the same paths. With Arabic serving as a lingua franca throughout the Muslim world, the Hajj was no less an intellectual clearing-house. The Holy Cities were for centuries centers for some of Islam’s great thinkers, who traveled there to perform the Hajj and then stayed on to study with the best and brightest. Provincial scholars, judges, lawyers, teachers, businessmen and traders from every corner of the earth shuttled almost routinely among North Africa, Egypt, Persia, India and Indonesia. The certificates of learning that Ibn Battuta earned in Makkah, for example, qualified him to land posts as a qadi, or judge, in Delhi, the Maldives and Indonesia, far from his native Tangier. Today’s Bangladeshis working in Silicon Valley or Saudi families thriving in Japan would hardly have surprised the people who took to the Hajj roads.

The Hajj was in effect a traveling university, as significant to the wider ‘ummah, or community of Islam, as any of its fixed institutions of education, culture and creativity. Some pilgrims—such as Ibn Battuta, Ibn ‘Arabi and Ahmad ibn Idris—became lifelong wanderers along the Hajj roads, returning several times to Makkah and Madinah to feed on and draw from the environment of passionate intellectual striving, then returning once again to the wider arcs of the Islamic world.

|

|

| |

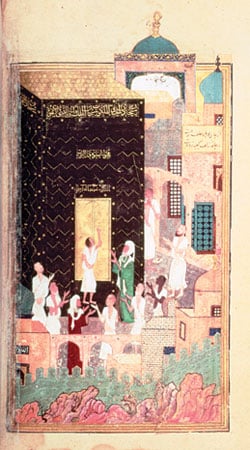

Pilgrims pray at the Ka’bah in the Great Mosque in Makkah. The painting, dated 1442, is by the Persian artist Bihzad, who created it as part of an edition of the Khamsa of Nizami. (Bridgeman Art Library / British Library.)

|

| |

|

The end of the Hajj caravans came surprisingly fast. It took a mere 75 years for steamships, trains, buses and aircraft to render obsolete the pilgrimage routes that had endured for nearly 13 centuries. In the late 19th century, particularly after the opening of the Suez Canal, increasing numbers of pilgrims journeyed to Makkah by ship via Yanbu‘ or Jiddah. Not only Egyptians took to the sea, but Syrians and Anatolians sailed from Beirut through the canal, and ever-increasing numbers of Indian and Indonesian pilgrims arrived across the Indian Ocean. The 1908 opening of the Hijaz Railway from Damascus to Jiddah sounded the death knell of the Damascus caravan. After World War II, the route to Makkah was marked out increasingly by air, until by the 1990's fully 95 percent of non-Saudi pilgrims (and more than a few of the Saudi ones) arrived on chartered or commercial aircraft. The remaining handful of overland pilgrims, mostly from Middle Eastern countries adjoining Saudi Arabia, traveled high-speed highways in air-conditioned buses.

The new modes of transport also brought an exponential increase in the numbers of pilgrims altogether. According to the Saudi Press Agency, the number of pilgrims who made the Hajj was fewer than 100,000 as recently as 1950. That number doubled by 1955, and in 1972 it had reached 645,000. In 1983 the number of pilgrims coming from abroad exceeded one million for the first time, and since the 1990's the numbers have exceeded two million. With this, the experience of the Hajj changed dramatically. To future historians and writers is left the task of assessing the impact of these changes on the world of Islam.

THE DAMASCUS CARAVAN

With the longest continuous history of any of the Hajj caravans, the Damascus caravan was also the best known and the largest. Its roots stretch back to the Umayyad caliphate in the seventh century. Under the Mamluks and then the Ottomans, it was led by the governor of Syria. It also generally included the most foreigners, which swelled to include Iranians and Iraqis brought north by the loss of the Baghdad-based route in the 13th century. The distance from Damascus to Madinah was about 1300 kilometers (800 mi), and the caravan normally covered it in 45 to 60 days.

Generally the camels for this caravan were supplied by villages in southern Syria and tribes on the Syrian steppe around Palmyra. They were delivered at Muzaryib, the caravan's chief staging point, about three days' journey south of the capital. The best records of the caravan are from the Ottoman era starting in the 1450's, though many of the traditions would date back to the Mamluks and even earlier. The caravan was further accompanied by the sürre amir, or “guardian of the purse,” an imperial officer from the Ottoman court in Istanbul.

From Muzaryib, the route ran across the fertile plains of Hauran, past the territory of the Druze people and over the rolling hills towards Roman Jerash. The flat stretch from Amman to Kerak to Ma‘an traversed the “brow of Syria,” an elevated plateau between the desert proper to the east and the hilly spine of the Rift Valley to the west. After a four-day stop near Kerak, the caravan would pass through Ma‘an and make its way east into the desert through the Pass of al-Sawan and south through Dhat al-Hajj and Wadi Balduh to Tabuk, where the pilgrims would stop for another four days. Continuing across the desert, the caravan pushed on to al-‘Ukhaydir, then Hijr (Madain Salih), al-‘Ula and finally Madinah and Makkah. (If the caravan was joining up with the Egyptian caravan, it would detour at Ma‘an to Aqaba and move into the Hijaz from there.)

After the Hajj, a secondary caravan, called the jurda, was sent from Damascus to meet and support the returning caravan.

|

|

| |

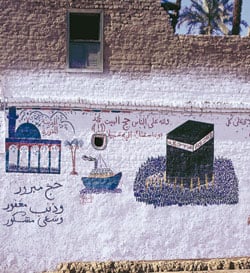

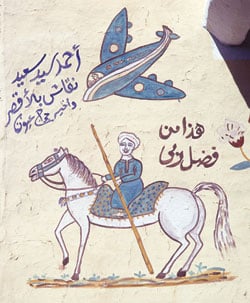

Paintings from the walls of houses in the Egyptian town of Farafra celebrate the residents’ recent pilgrimages—by ship and by air, respectively. (John G. Ross / Aramco World / PADIA.)

|

| |

|

THE EGYPTIAN CARAVAN

Pilgrims from the Maghrib (northwestern Africa ) and al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) would follow the land routes to Cairo. Like the Damascus caravan, the route from there took roughly 40 days, broken up into 34 stages, each some 45 to 50 kilometers (28–30 mi) long. The caravan would muster at Birkit al-Hajj (“Pilgrimage Well”), a village just north of Cairo. After about four days, it would proceed in no particular order to Ajrud, the formal marshaling ground northwest of Suez. There, under both the Mamluks and the Ottomans, a government-appointed amir al-hajj was placed in charge, responsible for organization, security and the caravan's on-time arrival at the Holy Cities.

One or two hours after sunrise on the day of departure, the caravan would form and proceed either south to Quzlum ( Suez ) or, more typically, directly east. Both routes met at Thughrat Hamid, and then crossed the Sinai through Qala‘at al-Nakhl to the port of Aqaba, which marked the quarter-way point of the journey. From Aqaba, the pilgrims made their way to al-Bad', and then followed the coast to Rabigh. At Rabigh they joined the Darb Sultani, “The Sultan's Way,” connecting Madinah and Makkah.

Starting in the 12th century, the Crusaders' occupation of a large swath of territory from Aqaba to Edessa effectively barred the Egyptian caravans from crossing the Sinai. (They also forced the Syrian cara vans far out east into the desert.) In response, the Egyptian caravan turned south from Qus to the Red Sea port of Aydhab, where pilgrims were often packed onto overloaded ships to sail to Jiddah. Noting this as well as the extortionate prices Aydhabis charged for the 20-day voyage, historian Ibn Jubayr called the port “one of God's least-favored places.”

This particular difficulty ended in 1266 with the end of the Crusader presence, the year the Mamluk Sultan Baybars sent the kiswah—the embroidered cover for the Ka'bah that is made anew annually—along with the Hajj caravan by the Sinai route. In addition to the main caravan, Cairo rulers organized a secondary caravan that was sent out three or four months before the main one, which allowed some pilgrims to spend a longer time in the Holy Cities to perform optional rites in a more leisurely fashion.

|

|

| |

Paintings from the walls of houses in the Egyptian town of Farafra celebrate the residents’ recent pilgrimages—by ship and by air, respectively. (John G. Ross / Aramco World / PADIA.)

|

| |

|

THE BAGHDAD CARAVAN

From Iraq, the route to the Hijaz, as well as the pace a traveler had to keep up, was determined by the location of water sources. Scattered thinly over the 1500-kilometer (900-mi), trans-peninsular route, these sources had from time immemorial tenuously linked the two areas. Assyrian armies, Babylonian and Egyptian merchants and countless others had relied on them.

With the accession of the Abbasids to the caliphate in ad 749 and the transfer of the capital from Damascus to Baghdad the following year, there was new interest in facilitating the pilgrimage from Kufa and from Basra farther south. Unlike their predecessors, the Umayyads, the Abbasid rulers had a penchant for leading the Hajj in person, and they put huge sums not only into the route, but also into the expansion and adornment of the Holy Cities.

In 751, al-Saffah, the first Abbasid caliph, ordered fire signals and milestones established from Kufa to Makkah. His successor, Mansur, ordered additional forts built. Mansur's successor, al-Mahdi, undertook projects to clear and level the way. By 776, the passage could be made so quickly—at least under demonstration circumstances—that al-Mahdi had ice delivered to him in Makkah from Iraq.

The most generous patrons, however, were the storied caliph Harun al-Rashid, who ruled from 786 to 809, and his equally famous wife Zubayda. The caliph made the pilgrimage six or nine times, including the one in 790 which, in fulfillment of a vow, he made entirely on foot. His final one, performed in 804, was the last Hajj ever made by a caliph.

Zubayda made five or six pilgrimages herself, the first in the company of her husband in 790. Her name is attached to two notable projects: The first established abundant drinking water in Makkah, and the second built at least 10 new rest stops and three new way stations along the route, as well as a number of water tanks. Ever since, the route has been known as Darb Zubayda (“Zubayda's Way”). At its height, the route included milestones, 54 major way stations with cisterns, reservoirs or wells, fire signal towers, hostels and fortresses—all paid for by the Abbasid treasury.

Zubayda made five or six pilgrimages herself, the first in the company of her husband in 790. Her name is attached to two notable projects: The first established abundant drinking water in Makkah, and the second built at least 10 new rest stops and three new way stations along the route, as well as a number of water tanks. Ever since, the route has been known as Darb Zubayda (“Zubayda's Way”). At its height, the route included milestones, 54 major way stations with cisterns, reservoirs or wells, fire signal towers, hostels and fortresses—all paid for by the Abbasid treasury.

The chief departure point for the Iraqi caravan was Kufa. Pilgrims starting from there crossed the Najd to Madinah, passing through Fayd just south of Hail. East of Madinah, the caravan would rest near al-Rabadha, where current archeology shows remains of large houses, fortified walls, watchtowers, mosques, pottery kilns, stone-working factories, jewelry shops and two large reservoirs.

A second and much smaller caravan, composed mostly of Iranians and others who did not wish to travel to Kufa, would set out from Basra following a more southerly route that passed through al-Hasa, then through al-Dir‘iyya, which became the Saudi capital in the 18th century. The two groups would meet at Dhat Irq, complete the Hajj circuit and return together.

This route fell into disuse following the Mongol destruction of Baghdad in 1258. Cities such as al-Rabadha that had depended on the Hajj caravans were slowly abandoned. The Ottoman Turks showed little interest in reestablishing the route. Iraqi, Iranian and other pilgrims from the East took the longer but safer route via Damascus.

OTHER ROUTES

There were several lesser caravan routes. Some Iranians would journey from the lower Euphrates area of Suq al-Shayukh, in the neighborhood of Meshed Ali. East and Central Africans would make their ways to Darfur in Sudan, and then proceed as a group to Assiut, Aydhab and across the Red Sea to Jiddah. Another African caravan, primarily composed of Nubians, would cross the Red Sea at Kosseir and gather at Yanbu‘ for the march to Makkah. Indian and Malay pilgrims followed the sea routes, and they gathered after their voyages at Jiddah. From much closer to the Holy Cities, Arabs from Yemen to the south and the Najd to the east might form their own bands, often convening at Taif, near Makkah.

Each of the above caravans would have its own amir and its own guides or agents (muqawwim), whose business it was to see to provisions, water and the like. Given the lower economic status of most of these participants, they tended to move more quickly since, in the words of Ibn Battuta, they were “seldom encumbered with a numerous retinue of servants and other attendants.”

|

|

David W. Tschanz (desertwriter1121@yahoo.com) has advanced degrees in history and epidemiology and currently works for Saudi Aramco Medical Services in Dhahran. He is the author of Petra & Madain Saleh: A Brief History, a book on the Nabataeans, and has recently completed a second book. |

|

|