|

| The ruins of an old Arab mill on the banks of the Guadalquivir River near Córdoba stand as a reminder of daily life in al-Andalus. |

Written by Greg Noakes

Photographed by Tor Eigeland

he year 1492 has long been a historical touchstone. Europeans and Americans in 1992 marked the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World, not without protests from those who felt that the hemisphere’s gains from the event were far outweighed by its losses. Spain was a focus of attention in that quincentennial year, in part because it was Columbus’s point of departure. There was another 500th anniversary to be marked in 1992, however, and it too involved Spain. While this event has also had important repercussions in world history, and remains the source of a lingering sense of loss, it has attracted much less attention. The event was the fall of the Muslim city of Granada (Gharnatah in Arabic), on the second day of 1492, to the forces of the Catholic kings of Castile, ending nearly eight centuries of Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula and closing one of the most turbulent and glorious chapters in Islamic history.

he year 1492 has long been a historical touchstone. Europeans and Americans in 1992 marked the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s “discovery” of the New World, not without protests from those who felt that the hemisphere’s gains from the event were far outweighed by its losses. Spain was a focus of attention in that quincentennial year, in part because it was Columbus’s point of departure. There was another 500th anniversary to be marked in 1992, however, and it too involved Spain. While this event has also had important repercussions in world history, and remains the source of a lingering sense of loss, it has attracted much less attention. The event was the fall of the Muslim city of Granada (Gharnatah in Arabic), on the second day of 1492, to the forces of the Catholic kings of Castile, ending nearly eight centuries of Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula and closing one of the most turbulent and glorious chapters in Islamic history.

As some historical accounts have it, Muslim armies first arrived in the peninsula in AD 711 at the request of one side of a civil war raging in Visigothic Spain. Muslim rule was accepted voluntarily by many Spaniards, and numbers of them accepted Islam. In 732, just 100 years after the death of the Prophet, Muslim troops crossed the Pyrenees to make their deepest advance into western Europe; they were checked at Poitiers in a battle that has rung down the centuries in western legend, but which Muslim chroniclers record, if at all, as a minor skirmish. The Muslims soon withdrew again and set about establishing Islam in Spain, in the territories they called al-Andalus. The society they developed was perhaps uniquely tolerant and heterogeneous, with Arab and Berber immigrants living side-by-side with Spanish Muslims, Christians and Jews. Intermarriage was fairly common.

Al-Andalus was ruled by the Umayyad caliphs in Damascus until 750, when the Abbasid dynasty came to power in the East. One Umayyad prince alone, ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Mu’awiyah, escaped and fled to Spain; there he established an independent Umayyad state in 756. The Andalusian rulers, sovereign politically, continued to regard the Abbasid caliphs as the ultimate religious authority for almost 200 years, but the eighth ruler of the dynasty, ‘Abd al-Rahman III al-Nasir, claimed the caliphal title for himself and his progeny in 929. The Andalusian Umayyad caliphate was the golden age of al-Andalus in terms of political power. The southern two-thirds of the Iberian Peninsula was united under the caliph in Córdoba (in Arabic, Qurtubah), and he was also an important player in North African affairs. It was the Umayyads who, through skill, cleverness and occasional ruthlessness, laid the foundation for the splendor of al-Andalus.

|

| Above: A Toledo Cathedral carving shows Castilians besieging a Muslim city. The fall of Toledo to the Christians in 1085 decisively loosened Muslim control over central Spain. Below: These silver dirhams circulated in 10th-century al-Andalus. Photo: Peter Keen / Gibraltar Museum. |

|

Between 1009 and 1031, however, a series of uprisings and a succession of weak rulers together led to the dissolution of the Umayyad state. Filling the vacuum, more than a score of independent petty monarchs emerged, called “party kings” or, in Arabic, muluk al-tawa’if, from the word ta’ifah (Spanish taifa), meaning “party” or “faction.” Though these rival kingdoms—some no more than city-states—were much weaker than the unitary Umayyad caliphate, the taifa period witnessed a flourishing of arts and learning as each ruler attempted to outdo the others in the prestige of his court. As David Wasserstein points out in The Rise and Fall of the Party Kings, the profusion of rulers also meant a profusion of patrons, so artists, scholars and scientists could find a sponsor, or even competing sponsors, with relative ease.

Nevertheless, weakened by chronic infighting, treacherous double-dealing and internal decadence, the taifa kings gave up considerable territory to the Christian kingdoms that were reasserting themselves in the north of the Peninsula. By 1085 the Castilians had taken the crucial city of Toledo, and the petty kings asked the new Almoravid ruler in Moracco, Yusuf ibn Tashufin, to intervene. The Almoravids (in Arabic, al-Murabitun, “The Garrisoned Ones”) were a puritanical dynasty that had arisen among the Berbers of far southern Morocco, and for a time they were content to assist the taifa kings militarily—but in 1090 Yusuf decided that his erstwhile hosts had to go, and the petty kings were swept aside. The Almoravids at first imposed their Puritanism and rigid religious orthodoxy, visible even in their art, on Spain, but in the end, though their faith remained pure, they themselves succumbed to the luxury and ease of al-Andalus.

The Almoravids’ faltering strength provided the Christian kingdoms with opportunities for reconquest, and by 1145 Almoravid Spain was reeling. The Muslim population rose in revolt and a new group of taifa monarchs asked the Almohads (in Arabic, al-Muwahhidun, “Those Who Profess God’s Unity”)—another puritanical movement from southern Morocco, which supplanted the Almoravids in North Africa—to intervene. The Almohads willingly obliged, and for a time the new North African rulers enjoyed some success in Spain. But the tide turned in favor of the Christians in 1212 at the Battle of al-‘Iqab, called in Spanish Las Navas de Tolosa, and within decades the Almohads had retreated back across the Strait of Gibraltar. Muslim cities fell one after another until 1260, when only the kingdom of Granada remained.

|

| Ibn Rushd, or Averroës, one of the great intellects of the 12th century, is honored by a statue in his home town, Córdoba. |

recariously balanced between hostile Christian powers to the north and rival Muslim rulers in Morocco to the south, Granada survived for almost two centuries more. Although they gradually ceded territory to the Spanish Christian forces, the Nasrid rulers of Granada, afraid of being swallowed by their rescuers, refused to turn to the Moroccans for assistance. Isolated politically, the Granadines lived on, on borrowed time.

recariously balanced between hostile Christian powers to the north and rival Muslim rulers in Morocco to the south, Granada survived for almost two centuries more. Although they gradually ceded territory to the Spanish Christian forces, the Nasrid rulers of Granada, afraid of being swallowed by their rescuers, refused to turn to the Moroccans for assistance. Isolated politically, the Granadines lived on, on borrowed time.

Yet, architectural historian John Brooks notes, “despite the general winding down of the organized political and military state during the last period of Muslim rule in Spain, this strikingly rich and original culture was still evolving.” Indeed, many of the most lavish and famous examples of Andalusian art and architecture date from period. Within its slowly shrinking enclave, Granada flourished magnificently, both artistically and culturally, until the end of the 15th century, when Catholic Spain overcame political division and the effects of the Black Death and the final stage of the reconquista began in earnest.

By the end of 1491 the armies of Ferdinand and Isabella were at the gates of Granada itself. There remained only one final act to be played out, a knell whose sorrow was to reverberate across the Muslim world and become legend. Granada’s ruler, Muhammad XII Abu ‘Abd Allah, known in the West as Boabdil, secretly agreed to hand over the city to the Christians in return for his safe passage out of Spain. As he left the city, Boabdil paused to look back at the Alhambra palace, the Generalife gardens and the rest of Granada. Stanley Lane-Poole relates Boabdil’s reaction in his classic 1887 work The Moors in Spain:

“Allahu akbar!” he said, “God is most great,” as he burst into tears. His mother Ayesha stood beside him: “You may well weep like a woman,” she said, “for what you could not defend like a man.” The spot whence Boabdil took his sad farewell look at his city from which he was banished for ever, bears to this day the name of el ultimo sospiro del Moro, “the last sigh of the Moor.”

Thus, on January 2, 1492, Muslim political sovereignty in Spain came to an end.

Muslims and people of Muslim origin had lived relatively unmolested in Christian areas before the fall of Granada and continued to do so immediately after; the city’s inhabitants received generous terms of submission and a large degree of religious freedom. In 1499, however, the Catholic monarchs’ guarantees were broken, and forced conversion of the Muslims was introduced. The Muslim population rebelled, but the revolt was quickly suppressed. In 1500 Spanish Muslims were presented with a stark choice: Convert to Catholicism or be expelled from Spain. While some Muslims did convert, other continued to practice their faith in secret, and the rest chose exile, principally across the Mediterranean in North Africa.

Although Muslim rule in Spain had ended, the rich cultural and intellectual legacy of al-Andalus survived, both in the Iberian Peninsula and throughout the world. Elements of the Islamic heritage can be found throughout Spain, and in recent years modern Spain has become more aware, and more proud, of the glories of this period of its history. Many place names, such as those of the port city of Algeciras (from al-Jazirah al-Khadra’, “green island”), the Guadalquivir River (from al-Wadi al-Kabir, “great river”), and the southern region of Andalusia itself, all come from the Arabic used in al-Anadalus. The Spanish language itself has been greatly influenced by Arabic, particularly in terms of vocabulary, and many terms of Arabic origin passed on from Spanish into English in the New World.

Some of Spain’s most famous architectural monuments, including Córdoba’s Great Mosque, Seville’s Giralda and Granada’s Alhambra, date from the Muslim period; architecture in southern Spain and Latin America borrows a great deal from Muslim builders, both in terms of materials used—tile, stucco—and design elements like central courtyards, abstract ornamentation, and creative use of water and fountains. The artisans and craftsmen of Spain after the reconquista remained largely Muslim, and they often received commissions from Spanish nobility; their work can easily be seen today throughout Andalusia—in the royal residence of Seville, the Alcázar (from the Arabic al-qasr, meaning “the palace”), for example.

The instruments, rhythmic patterns, vocal conventions and overall structure and organization of Andalusian music, derived directly from Arab precursors, have also had their effect on Spanish—and, by extension, Latin American—music. In some cases even the Andalusian melodies have been passed down intact.

The instruments, rhythmic patterns, vocal conventions and overall structure and organization of Andalusian music, derived directly from Arab precursors, have also had their effect on Spanish—and, by extension, Latin American—music. In some cases even the Andalusian melodies have been passed down intact.

The works of many of the most prominent thinkers and practitioners of al-Andalus, along with writings from the eastern Muslim world, were translated from Arabic into Latin by Spaniards. Through these translations, philosophical and scientific thought from the Greek and Roman worlds, preserved and expanded upon by Muslim scholars, passed into European consciousness to fuel both the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment.

Nevertheless, it was back in the Arab and Muslim worlds that Andalusian culture and society had their greatest impact, even before 1492. Many important contributors in Islamic intellectual history came from or worked in Muslim Spain: No account of the development of philosophy in Islam is complete without a discussion of Ibn Tufayl, who died in 1185, and of his pupil Ibn Rushd, who was born in Córdoba, became chief qadi, or judge, of Seville, and died in 1198. Ibn Rushd, known in the West as Averroës, made his most important contributions in his commentary on Aristotle, his refutation of al-Ghazali’s critique of philosophy, and his examination of the relationship between reason and religion. Much of Ibn Rushd’s thought prefigured the work of Thomas Aquinas.

In medicine, al-Andalus produced scholars like al-Zahrawi (died ca. 1013), who wrote extensively on surgery, pharmacology, medical ethics and the doctor-patient relationship. Ibn Zuhr (known in the West as Avenzoar), a century and a half later, was an advocate of clinical research and practical experimentation.

|

|

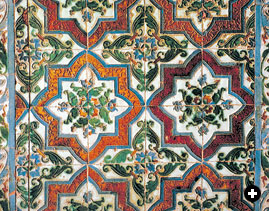

| Left: The tilework below decorates the Sala de las Dos Hermanas, or Hall of the Two Sisters, in the Alhambra. Right: A detail from an Arab water trough at the Alhambra Museum shows the common royal motif of lions attacking their prey. |

In literature, Ibn Hazm (died 1064) expanded traditional romantic poetry with his “Tawq al-Hamamah” (“Dove’s Necklace”), which expounds on the various forms of chivalric love and the joys and sorrows it produces. The courtly muwashshah form of poetry passed from al-Andalus into North Africa, and influenced the development of both literature and music in the Maghrib. The classical music of North Africa, which remains popular, is still known as “Andalusi music.”

The most immediate effects of the events of 1492 to 1500 were felt in the great cities of North Africa, where most of the Andalusian refugees fled after their expulsion. Residents of each Spanish city tended to migrate to a particular Maghribi city, so that many exiles from Valencia ended up in Tunis, those from Córdoba in Tlemcen, refugees from Seville in Fez, and so on. Andalusian scholars, merchants and artisans in many ways revitalized North African society, enriching Maghribi culture and adding a fresh influence to the existing Arabo-Berber traditions. This influence continued for some 200 years, until the Andalusian heritage had been completely integrated into North African life. Nonetheless, many present-day Moroccans, Algerians and Tunisians can still trace their lineage back to a specific city of al-Andalus.

Its intellectual, cultural and esthetic contributions aside, however, al-Andalus left a bittersweet emotional legacy to the Arab and Muslim worlds. Though the sense of loss is most pronounced in descendants of the Andalusian exiles, the memory of al-Andalus retains its emotive power throughout the Islamic world. The 20th-century Iraqi writer Daisy Al Amir, for example, takes contemporary England as the setting for her allegorical story “An Andalusian Tale,” about an Arab student who meets “a Spaniard who recognized his Arab ancestry” and is proud of his Andalusian heritage. Tunisian film director Nacer Khemir borrows his title and his melancholy subject matter from ibn Hazm in the 1990 film “Le colier perdu du colombe” (“The Dove’s Lost Necklace”). Khemir’s fanciful costumes, dream-like architecture, shimmering colors and stunning cinematography give life to the esthetic ideal of Al-Andalus.

Its intellectual, cultural and esthetic contributions aside, however, al-Andalus left a bittersweet emotional legacy to the Arab and Muslim worlds. Though the sense of loss is most pronounced in descendants of the Andalusian exiles, the memory of al-Andalus retains its emotive power throughout the Islamic world. The 20th-century Iraqi writer Daisy Al Amir, for example, takes contemporary England as the setting for her allegorical story “An Andalusian Tale,” about an Arab student who meets “a Spaniard who recognized his Arab ancestry” and is proud of his Andalusian heritage. Tunisian film director Nacer Khemir borrows his title and his melancholy subject matter from ibn Hazm in the 1990 film “Le colier perdu du colombe” (“The Dove’s Lost Necklace”). Khemir’s fanciful costumes, dream-like architecture, shimmering colors and stunning cinematography give life to the esthetic ideal of Al-Andalus.

|

| The Alhambra’s Mirador, or viewing turret, of Lindaraja, above, featuring a double-arched window with delicate muqarnas stalactites, overlooks a favored garden. |

In the Islamic world today, Muslim Spain is invoked on two levels. First there is the memory of the land itself: the flowing rivers and green fields of southern Spain, the magnificent mosques and places, the flourishing culture. This is the land that Andalusian exiles refer to still as al-firdaws al-mafqud—paradise lost—and whose passing the Valencian exile Ibn Amira mourned in his “Epistola a un Amic:”

An ocean of sadness rages inside us, Our hearts, desperate, burn with eternal flames… The city was so beautiful with its gardens and rivers, The nights were imbued with the sweet fragrance of narcissus.

Al-Andalus is remembered on another level as the one area that was once—but is no longer—part of the Muslim world. Until the middle of this century, Muslims have withstood Mongols, Crusaders, empire-builders and settlers and still emerged with their Islamic identity intact—except in Spain. Even the Communist regimes of China and the Soviet Union failed to root out Islam, failed to deracinate their Muslim populations, despite vast expenditures of time, of treasure and of blood. The fact that the rest of the Muslim world has retained its religious identity over some fourteen centuries rife with political, social, cultural and technological changes makes the exception of Spain that much more painful to Muslims.

It is nonetheless a pain that lies well beneath the surface. Contemporary Muslims are less likely to think of Spain as a historic enemy, or still less a territory to be reclaimed, than as an important trading partner, a fellow member of the family of nations, and—especially for North Africans—a source of expatriate employment. Muslim countries maintain cordial relations with Madrid and a number of them opened pavilions at EXPO ’92 in Seville and sent teams to the Olympics in Barcelona.

|

| Above the western portal of Córdoba’s Great Mosque, a decorative panel displays interlaced arches, stucco elaborately carved in vegetative and floral patterns, and a pious inscription. |

And though, over the years, lost Muslim Spain has been much idealized in the Islamic world, there remains an appreciation of the factors behind its downfall. Some of these were external, such as the unification and expansion of the Christian kingdoms of Spain and the geographic and political isolation of al-Andalus from the rest of the Muslim world. There were also internal factors that contributed to the decline of al-Andalus, particularly the rivalries that weakened and divided Muslim Spain, the greed and self-indulgence that gripped its elites, and the loss of a unifying religious vision.

On the other hand, Islamic Spain was an immensely fertile ground for learning, producing a long series of intellectual, esthetic and scientific advances attributable to Muslim, Christian and Jewish thinkers and the atmosphere they created. This blossoming was due in part to the spirit of tolerance that prevailed for much, though not all, of the history of al-Andalus—a tolerance extended not only to other religious groups but operative within Muslim society as well.

Despite the passage of 500 years, al-Andalus continues to cast its spell. As the birthplace of some of the world’s outstanding scholars and artisans, the home of dazzling architectural masterpieces, and the setting of a brilliant society notable for both the height of its achievements and the depths of its decadence, al-Andalus retains its emotional impact and its privileged place in Muslim historical memory.

| Greg Noakes, an American Muslim and former news editor of The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, writes frequently on Islamic issues and North African matters. He is a staff writer for Saudi Aramco in Dhahran. |

| Tor Eigeland is a free-lance writer and photographer who lived in Spain

for many years and returns frequently to Andalusia. |