By James Parry

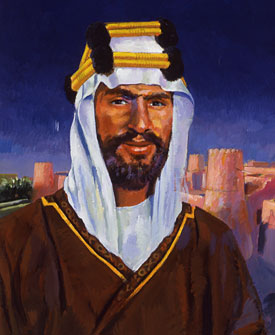

hese remarks were written by the British traveler Gertrude Bell in a letter she wrote following a meeting at Basra (now in southern Iraq) in 1916. Never easy to impress, Bell was nonetheless clearly awestruck by her first encounter with a man who at that time was already shaping the history of Arabia and was later to become a significant player on the world stage. Although the meeting was essentially a political affair, it revealed much about the personalities involved, in particular the startling impact ‘Abd al-‘Aziz had on his British hosts.

hese remarks were written by the British traveler Gertrude Bell in a letter she wrote following a meeting at Basra (now in southern Iraq) in 1916. Never easy to impress, Bell was nonetheless clearly awestruck by her first encounter with a man who at that time was already shaping the history of Arabia and was later to become a significant player on the world stage. Although the meeting was essentially a political affair, it revealed much about the personalities involved, in particular the startling impact ‘Abd al-‘Aziz had on his British hosts.

At the time, the British were intrigued by this man who was emerging as a potential leader from the turmoil and hardships of inner Arabia. Desperate to court him once war with the Turks became a reality in 1914, the British government engaged in a long-term strategic relationship that benefited both sides: British support aided the Saudis in their efforts to reunify the country, which meant driving the Turks from the region, and the rising Arabian polity that resulted meant that Britain could look upon a friendly government in a part of the world that the British regarded as essential to the defense of the centerpiece of their empire—India. Yet throughout the years, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn ‘Abd al-Rahman Al Sa‘ud, commonly known to Westerners as Ibn Saud, remained something of an enigma to the British. To this day, his personality and achievements are surprisingly little known outside the region in which he played such an instrumental role.

At the time, the British were intrigued by this man who was emerging as a potential leader from the turmoil and hardships of inner Arabia. Desperate to court him once war with the Turks became a reality in 1914, the British government engaged in a long-term strategic relationship that benefited both sides: British support aided the Saudis in their efforts to reunify the country, which meant driving the Turks from the region, and the rising Arabian polity that resulted meant that Britain could look upon a friendly government in a part of the world that the British regarded as essential to the defense of the centerpiece of their empire—India. Yet throughout the years, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn ‘Abd al-Rahman Al Sa‘ud, commonly known to Westerners as Ibn Saud, remained something of an enigma to the British. To this day, his personality and achievements are surprisingly little known outside the region in which he played such an instrumental role.

‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s roots ran deep in the heart of Arabia. His family, the Al Sa‘ud, traces its origins back more than 500 years. Traditionally, it has been associated with the central Arabian province of Najd, most particularly with the cities of al-Dir‘iyah and, later, Riyadh. The family history is one of the most distinguished in Arabia, but like all noble lines, it was subject to the political inconstancies of the day. At the time of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s birth in 1880 or thereabouts, central Arabia had fallen into political fragmentation, and theAl Sa‘ud in Riyadh were engaged in a power struggle with the rulers of the city of Hayil, the al-Rashids. This conflict led ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s father, ‘Abd al-Rahman, to evacuate his family from Riyadh in 1891.

From his early years, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz had been exposed to the power politics and warfare of Arabia’s ruling families. However, despite (or perhaps because of) the uncertain and lawless nature of the political context in which he grew up, he found enduring security and comfort in the Qur’an and in the discipline of regular prayer. This highly developed sense of faith, order and personal duty characterized his life, and it played more than an incidental role in his political success.The Al Sa‘ud initially took refuge with the al-Murra, a Bedouin tribe living in a remote and inaccessible area on the edge of the Rub’ al-Khali, the Empty Quarter, to the south of al-Hasa, an oasis in eastern Arabia. This experience ofliving among the al-Murra had a profound impact on ‘Abd al-‘Aziz. It was from them, he would say in later years, that he derived his deep love of the desert, of horsemanship and of the simple values that sustained the Bedouin both physically and spiritually.

In 1893, the Al Sa‘ud were invited to Kuwait by its ruler, Shaykh Muhammad Al-Sabah. By now ‘Abd al-‘Aziz wasa young man, conspicuously tall and strong, and he soon became great friends with Shaykh Muhammad’s half-brother, Mubarak. After Mubarak seized power from his brother, ‘Abdal-‘Aziz was invited to attend the daily majlis, or royal audience, at which petitions were presented and grievances heard. At these frequently acrimonious, politically charged sessions, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz saw at first hand the daily practices of government and international politics, and as he observed he had ample opportunity to reflect upon his own family’s situation. Najd had been central to the first and second Saudi states, and its loss engendered a deep sense of resolve in ‘Abd al-‘Aziz to act to recover his patrimony, to restore the Al Sa‘ud to the leadership of central Arabia.

In early 1901, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz sawan opportunity. Joining a raid led by Shaykh Mubarak from Kuwait intoal-Rashid territory, he seized Riyadh from the al-Rashids and besieged its fortress, al-Masmak. He held the city for three months before he was forced to withdraw. He immediately began to plan a new offensive, which was to lead to the event that has defined Arabia’s history ever since.

Taking advantage of the fact that most of the al-Rashid forces were deployed in a counterattack against Kuwait, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz correctly judged that this would be the most effective time to try and seize Riyadh permanently. In a daring raid, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and 40 men stormed the al-Rashids’ garrison at Masmak fort early on January 15, 1902. (See "There were 40 of us...") Overpowering those inside, the Saudis seized control of the city and, welcomed as a liberator, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz later that day led Riyadh’s inhabitants in prayer. Still only in his early twenties, he was now at the forefront of contemporary politics, and he had brought his family to the threshold of renewal.

Acutely aware that his family’s hold on Riyadh must not be allowed to slip again, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz set about forging alliances with local tribes in hopes of undermining the al-Rashids’ political power base.

Success at diplomacy was backed up by arms, and bloody battles continued between the two warring families. Open conflict between Al Sa‘ud andthe al-Rashids ended with the death in battle of Ibn Rashid in 1906, and the al-Rashids withdrew to their power base in Hayil, in northwestern Arabia. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz then turned his attention to other centers of opposition, and over the next few years, he personally led his men to victory on many occasions.

His behavior in conquest was notable for its magnanimity: Reprisals were rarely allowed, and generally the vanquished were welcomed back as brothers. Often, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz took wives from the ranks of those he had defeated. Such actions were primarily political, part of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s overall strategy of inclusion rather than division. This even extended to the al-Rashids, who continued to skirmish with ‘Abd al-‘Aziz through the early 1920’s. Ever mindful of the need to keep an eye on one’s potential foes, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz later welcomed the surviving members of the al-Rashids into his court, where they remained and were treated well, as befitted their noble status.

Feeling adequately secure at home in Najd, in 1913 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz marched dramatically onto the international stage, seizing first the Turkish garrison at Hofuf and then the coastal towns of al-‘Uqayr and Qatif, thus winning control of the Gulf coast. With this campaign, he brought into the Saudi remit an area that was, by virtue of its oil reserves, to provide unparalleled wealth for his nation in later years. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s more immediate success, however, centered around his astute calculation that on the one hand, the Turks were so weakened as to be incapable of resisting his advance and, on the other, that the British would be sufficiently concerned to start taking him seriously. This they did, as is clear from a report made to the India Office in 1914: “The Arabs have now found a leader who stands head and shoulders above any other chief and in whose star all have implicit faith.”

Turkey’s defeat in World War i left a political vacuum that ‘Abd al-‘Aziz had been readying himself to fill for some time. By 1920 he had assumed control over ‘Asir in the southwest and over the al-Rashid stronghold of Hayil in the north. He was then able to turn his attention to the Hijaz, in which were located the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah and the major port of Jiddah. In 1927 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was recognized as King of the Hijaz and Najd and its Dependencies, with Riyadh and Makkah as his two capitals.

These years also marked the beginnings of modern Arabia. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz understood the potential advantages Western technology offered; the importation of a fleet of automobiles and, later, the building of airstrips gave him the means of reaching distant parts of his territory in a fraction of the time required previously. He also ordered the creation of an extensive information network based on the wireless telegraph, through which he was able to extend his “eyes and ears” across the country.

The creation of a formal, modern system of government also dates from this time, with the establishment of the first ministries, although ‘Abd al-‘Aziz continued to exercise a high level of personal control over the activities of the state for the rest of his life. He was by now ruler of a dominion three times the size of France and, in 1932, proclaimed the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It marked the culmination of a process started more than three decades earlier, and as King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn ‘Abd al-Rahman Al Sa‘ud, he reigned over his people for an additional 21 years before his death in 1953. Since then, his heirs have continued to rule the country he established.

By any standards ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s achievements are astonishing. He rose from leader of an exiled clan to participant on the post-World War II international stage, which saw him meeting with both British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to exchange views on issues of common interest, including the subject of Palestine. Inheritor of a fragmented and impoverished land, he welded the tribes into an incipient nation, imposing both central authority and, eventually, the rule of law. At the time of his death, Saudi Arabia enjoyed both unparalleled wealth and security, a situation directly attributable to ‘Abd al-‘Aziz.

Today, the scale and significance of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s impact is even clearer than in 1953. Not only did he establish a new state, but he structured it to give it room for continued strength and development. Aware that the fledgling nation would be ill-equipped to function in the 20th century without industrial modernization, he was eager to embrace technology; however, he was no less aware that change had to be selective and gradual if it was to be accepted by the citizenry and be of lasting benefit. The well-known Arabist and historian Leslie McLoughlin pointed out that “it was the insight of Ibn Saud that slow change without disabling disputes was better than speed of change with great disruption.” Central to this process was the long search to expand the Kingdom’s sources of revenue, andto this end, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz granted the first oil concession as early as 1923. Although this venture bore no fruit,it was the first step in an endeavor of lasting significance.

Paramount in his success were ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s personal qualities. He was a complex character, and something of a paradox in the sense that he exhibited wide-ranging, often contradictory attributes. These frequently showed themselves in rapid succession, with fierce bursts of temper followed almost immediately by acts of great tenderness and compassion. But he commanded respect at all times, and by a combination of charm and authority secured the personal and political commitment of his people. The writer Amin al-Rihani noted how ‘Abd al-‘Aziz always found time to speak to those around him and was never at a loss for words.

‘Abd al-‘Aziz was both a brave anda cautious man. His personal courage when leading his troops into battle is legendary, but it is equally well-established that he sought to avoid excessive bloodshed wherever possible. By breaking the historical pattern of strife and conflict, he was able to set his people on a new path of peace and prosperity, and his statesmanship set new standards for political behavior, ones that placed him apart from most of his contemporaries.

‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s profound religious faith gave him a conviction and a self-confidence that propelled him toward what he considered the just destiny of his family and country. Yet he was aware of the diversity of the nation he was bringing together, and he repeatedly warned followers he considered overzealous that they must not replace dissent with division and retribution. The long-term impact of this notion of nation-building is only now becoming clear, as the world witnesses the disintegration of states in other parts of the world within which a sense of inclusion has broken down.

‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s profound religious faith gave him a conviction and a self-confidence that propelled him toward what he considered the just destiny of his family and country. Yet he was aware of the diversity of the nation he was bringing together, and he repeatedly warned followers he considered overzealous that they must not replace dissent with division and retribution. The long-term impact of this notion of nation-building is only now becoming clear, as the world witnesses the disintegration of states in other parts of the world within which a sense of inclusion has broken down.

We cannot know for sure the direction Arabia’s destiny would have taken had ‘Abd al-‘Aziz not risen to such prominence. It is quite likely that the political divisions he inherited would have continued unabated under anyone of less forceful character and drive, and that Arabia would have remained a warring collection of disparate factions, spiraling into chaos and, perhaps, colonial domination. With such acute political insecurity, the economic gains made possible by the discovery of oil well might have been squandered anda unique opportunity for nationaladvancement lost. Equally clear is the fact that the circumstances of the day called for leadership of singular ability. In ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, personal staturemarried with circumstance to producea man who led his people from a fractious poverty into secure prosperity.

|

In the early 18th century, north of Riyadh, a religious leader was born who, in alliance with the House of Sa‘ud, would pave the way for the establishment of the modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. His name was Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab. The son of a qadi, a religious judge, he studied in Makkah, Madinah, Basra and al-Hasa before returning to Najd. By the time he returned, Shaykh Muhammad, as he was thereafter known, had become familiar with the currents of religious thought and the great political and social problems of his time. By then, too, he had concluded from his observation of the world and his wide reading that reforms were imperative. He began to call for a return to basic principles of Islam as contained in the Qur’an and the sunnah, or example of the Prophet.

Like most reformers, Shaykh Muhammad ran into opposition. He was driven from his home town, al-‘Unayzah, and forced to take refuge in the town of al-Dir‘iyah, very close to present-day Riyadh. The ruler there was Muhammad ibn Sa‘ud, who met Shaykh Muhammad and welcomed him. The year was 1745, and this meeting marked the beginning of the first Saudi state.

The two men—one an idealistic reformer and the other an astute chieftain from among the many tribes of Najd—formed an immediate warm regard for one another’s qualities, and established a relationship that links their descendants to the present day.

As Shaykh Muhammad was an eloquent and sincere preacher, his uncompromising reaffirmation of the basic beliefs of Islam soon won many followers. It also alarmed many leaders in Najd, especially those in independent Riyadh, so near al-Dir‘iyah. The nascent movement, whose followers called themselves al-Muwahhidun, “those who affirm the Unity of God,” or “Unitarians,” was seen as a threat to established patterns of authority.

Muhammad ibn Sa‘ud died in 1765, but under his very able son and successor, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, the Muwahhidun movement continued. In 1773, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz—brother of King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s (Ibn Saud’s) great-great-grandfather—captured Riyadh, and within 15 years controlled all of Najd. Then, in the winter of 1789–1790, the Muwahhidun crushed the paramount tribe of al-Hasa, in today’s Eastern Province.

In 1803 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was succeeded by his son Sa‘ud, and within a few years the territory controlled by the House of Sa‘ud, or Al Sa‘ud, as it is known in Arabic, extended over most of the Arabian Peninsula, including much of what is today Oman, parts of Yemen, and the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah. To administer this territory, the peninsula was divided into 20 districts, with a loyal member of the reform movement as governor of each, and a qadi in charge of religious matters and public education.

In Constantinople, meanwhile, the Ottoman sultan had been alarmed by these incursions in what were, nominally, territories of the Ottoman Empire. He therefore ordered Muhammad ‘Ali, governor of the Ottoman province of Egypt, to undertake a punitive expedition against the Saudis and to reestablish Ottoman authority over the holy cities.

Although his first forces, commanded by his son Tusun Pasha, were badly defeated, they did take Makkah. In 1818, his second son, Ibrahim Pasha, arrived in Najd with the full power of the Egyptian army behind him. Besieging the Saudi ruler ‘Abd Allah, who had succeeded Sa‘ud, Ibrahim captured al-Dir‘iyah, sent ‘Abd Allah a prisoner to Constantinople, and leveled al-Dir‘iyah. He destroyed forts and other defense works, encouraged local rivalries and, thinking he had destroyed Al Sa‘ud forever, returned to Egypt a year later.

In the following years, a number of mutually antagonistic local amirs in Najd tried to profit from the disruption of the Saudi state. These ambitions, however, were thwarted by Turki ibn ‘Abd Allah, a close relative (though not the son) of the dead ‘Abd Allah.

During the siege of al-Dir‘iyah, Turki had taken refuge in a nearby town, but in 1823 he felt the time was ripe for a counterattack. Entering al-Dir’iyah without a fight, he immediately moved against Riyadh, which he took as well, founding at that time the second Saudi state. He was also the first member of the House of Sa‘ud to make Riyadh his capital.

Turki ruled for 11 years. By the time of his death in 1834, he had largely restored the boundaries of the Saudi state to what they had been before the Egyptian invasions, though he did not recover the holy cities. He was succeeded by his son Faysal, who previously had been captured and then had escaped from the Egyptians. Faysal was faced with yet another Egyptian attempt to establish control over Najd. In 1838 he was captured once again, bravely giving himself up to the enemy rather than see his loyal followers slaughtered.

For the second time, he was taken to Egypt and imprisoned. For the second time too, he escaped, and he made his way back to Najd in 1843 in an exploit that added to his popularity among the tribes and also marked the end, for a while, of Ottoman efforts to quell the House of Sa‘ud. Muhammad ‘Ali was growing old, and the Ottomans, distracted by wars in Moldavia and Walachia, eventually had to content themselves with exercising only titular control of the Hijaz.

With the death of Faysal in 1865, this relatively brief period of peace and prosperity came to an end. First, rivalry over the succession weakened Saudi unity. Then, taking advantage of the Saudis’ internal conflict, the Ottomans occupied much of the eastern seaboard and the oasis of al-Hasa. Landing in 1871 at Ras Tanura, the present site of a Saudi Aramco oil refinery and shipping terminal, the Turks took Qatif, then marched 160 kilometers to Hofuf, the main town of al-Hasa, where they overcame stubborn resistance put up by the Saudi governor and occupied the fortress.

Two other events, however, overshadow this invasion, which had ambitions to carry on to Najd but in fact went no further. One was the birth of a son to ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Faysal, the man who had emerged as the reigning head of the House of Sa‘ud. The son—who would later create the modern-day Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—was ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn ‘Abd al-Rahman Al Sa‘ud. The other event was the rise to power of a rival dynasty, al-Rashid, which led to a conflict that would occupy the Saudis, and young ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, for decades.

Based in north-central Arabia, the al-Rashids had taken advantage of the uncertainties over the Saudi succession to install a deputy governor in Riyadh, in Saudi territory. In response, ‘Abd al-Rahman attacked Riyadh and recaptured it in 1890. His rival, Muhammad ibn Rashid, in turn marched on Riyadh and, finding the defense too strong for a direct assault, besieged it. During the siege he cut down a large number of date palms on which the townspeople depended for sustenance, a common practice in Arabian warfare in that period. After 40 days of this harsh but indecisive activity, Ibn Rashid proposed negotiations with the defenders. In the Saudi delegation was a young boy making his debut on the stage of history—‘Abd al-‘Aziz.

The truce that was arranged as a consequence of these negotiations was short-lived. Muhammad ibn Rashid soon led his men to the area of the Qasim, in northern Najd, where he attacked and routed the Saudis at the battle of al-Mulayda on January 21, 1891. Isolated and bereft of allies, ‘Abd al-Rahman sent his women and children to the protection of the ruler of Bahrain, who was a friend, while he himself, with no hope of returning to Riyadh, took to the desert south of the city, where he had friends among the tribes. For a time, ‘Abd al-Rahman and a handful of loyal followers roamed the fringes of the Rub’ al-Khali, but later they moved on to Qatar and then to Bahrain. Finally, they took refuge in Kuwait, where they spent the better part of a decade.

For young ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, the years he and his father spent in Kuwait as guests of the ruler, Mubarak Al-Sabah, provided valuable insights into international politics. Mubarak was an able politician and Kuwait, strategically placed at the head of the Arabian Gulf, was then the focus of western activity in the area. The British had special treaty relations with Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman and the shaykhdoms on the Trucial Coast (now the United Arab Emirates); the Russians, as part of their centuries-old search for a warm-water port, were probing for outlets in the Arabian Gulf; and both the Germans and the Turks, in an attempt to challenge Britain’s hegemony in the Gulf, were looking toward Kuwait as the possible terminus of the Berlin-to-Baghdad railway.

As he observed the international negotiations of Mubarak Al-Sabah, however, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz also kept an intent eye on the al-Rashids, now allied with the Turks, who still occupied al-Hasa.

In 1901, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, then in his early twenties, decided that it was time for the House of Sa‘ud to win back the lands wrested from it by Ibn Rashid and the Turks. As the entire force the Saudis could muster at this time consisted of only 40 men, ‘Abd al-Rahman, his father, tried to dissuade him. But ‘Abd al-‘Aziz persisted, and toward the end of the year he set off for Najd. Within two months he would be victorious.

—Adapted from the book Saudi Aramco and Its World (1995) |

|

Free-lance writer James Parry served several years with the British Council in East Africa and Oman. He writes on the history and cultures of the Arabian Peninsula from his home in Norfolk, England. |