Written by Richard Covington

Photographed by Kevin Bubriski

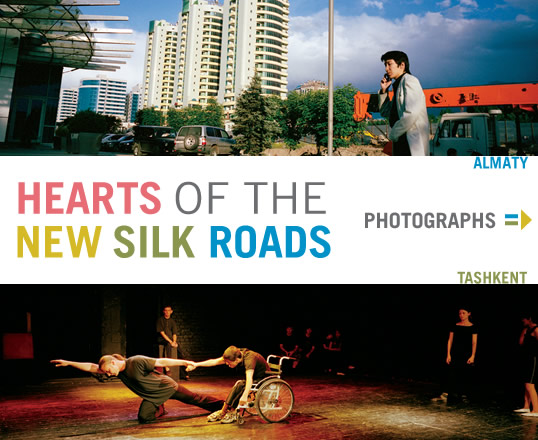

From my seat in the dance studio,

I watch as Valera props his trembling arms on a table and,

with his back to the audience, struggles to raise his severely paralyzed 23-year-old body from the wheelchair. After great effort, he finally stands. Anton, a powerful, 30-year-old dancer, gently grasps his arms and pushes the wheelchair aside. Together, the pair begin slow, graceful, improvised movements. It is clear that, although Anton is supporting him, Valera is mastering his own fear, controlling involuntary spasms of his arms and legs to step in rhythm with the recorded music. The triumph of his spirit over his body is a near miracle, and Anton guiding him around the floor is a complementary vision of compassion. I suddenly find myself in tears.

In these two capitals, I encountered artists, film and theater directors, actors, historians, archeologists, economists, sociologists, preservationists, scientists, hydrologists, museum curators, artisans, musicians, doctors, social workers, teachers, high-school and university students, NGO staffers and many moonlighting taxi drivers. (In Tashkent, I was told, more than half the adult males who own cars use them as taxis for extra income.) The businessmen I found were modern Silk Road nomads, roaming by jet, train and SUV. I met not a single camel driver.

But for some 1600 years—from the end of the second century BC to the middle of the 15th century—camel, horse and donkey caravans traversed Asia from China to the Mediterranean, following a network of routes across steppes and deserts, mountains and plains. Precious metals and stones, ceramics, spices, paper, perfumes and, of course, Chinese silk traveled west in exchange for cotton and wool textiles, glass, amber, wine and carpets. Along with trade came exchanges in science, medicine, technology, ideas and religions. From India, Buddhism filtered to China and Japan; Islam, Judaism and Nestorian Christianity moved east from the Mediterranean; and Manicheanism and Zoro-astrianism spread eastward from Persia.

In the heyday of the Silk Roads, the site of present-day Almaty was a compact oasis of yurts at the northern foot of the 4000-meter (13,000') Zailiysky Alatau mountains. Destroyed by the Mongols in the 14th century, the settlement was rebuilt in the 1850’s as a Russian frontier post, first called Vernyi, then Alma-Ata (“Father of Apples”).

Today’s city of 2.7 million inhabitants (in a country of 14.7 million) is the leafiest I’ve ever seen. “When I first arrived here 30 years ago from Ukraine, I wondered where all the buildings were,” says Ivan Apanasevich, an architectural preservationist, laughing. “All I could see was trees.” Apanasevich, a forthright, voluble man with close-cropped gray hair, works for USAID, but his passionate avocation is the uphill battle to rescue Almaty’s dwindling stock of historic buildings, many built of plaster-covered wood to resist earthquakes after a massive tremor leveled much of the city in 1887. In today’s overheated and largely unregulated real-estate market, developers are bulldozing swaths of Almaty’s vernacular architecture. Apanasevich is foregoing lunch to give me a whirlwind tour of what remains of the city’s czarist legacy.

“There’s no zoning, no building classification, no historic preservation,” Apanasevich laments as we admire the interlacing stucco flowers decorating a children’s library. Its blend of Palladian columns and glittering blue mosaic glass, an echo of Samarkand, makes it one of the city’s gems. A few blocks away, dozens of wood-frame homes that embody traditional Russian country architecture are being dismantled. Across the street, whitewashed buildings, embellished by green and blue shutters, pedimented windows and intricate decorative friezes, will soon make way for multi-family apartment blocks.

At the corner of Furmanova and Kurmangazy streets, we marvel over a superb 1906 mansion, a neo-Baroque confection, painted an arresting aqua-blue pastel color and trimmed in white stucco, one of the best-preserved czarist-era buildings in the city. Further down Kurmangazy, we pass a brand new, high-rise office building faced in beige limestone. A Korean–Japanese restaurant on the ground floor has opened so recently that it doesn’t yet have a sign. “No different from Singapore or Shanghai,” sniffs Apanasevich deprecatingly.

These days, Almaty’s ambitious pulse indeed seems to beat in rhythm with those cities. Mercedes convertibles and SUV’s roar up its boulevards or idle in infernal traffic jams. More than 500,000 vehicles clog urban arteries every day. Flush with oil and gas wealth and eager to flaunt it, the moneyed classes flood glitzy shopping malls and tony boutiques, snapping up luxury French jewelry and suitcases, Hungarian porcelain and $2000 Italian suits. Next to an outdoor vendor doing brisk business in steaming plates of plov (rice with meat, carrots and onions) and shashlyk (skewered meat), one food emporium near the opera house stocks hundreds of French and Italian wines, Chinese pastries and Kenyan coffee.

Skateboarders clatter down the pavement in front of the old Parliament building, now home to the Kazakh–British Technical University. Up the street, prosperous businesspeople and families crowd into the Soho Almaty Club, an upscale restaurant decorated with Beatles posters, where they sample pizzas, quesadillas, burgers and other exotic western fare while a local singer belts out Abba tunes. Around midnight, the Cuba club collects a $17 cover charge to hear Bugarabu, a drumming trio whose leader trained in New Delhi and draws his incendiary rhythms from traditional Kazakh shamanistic drumming. With an annual economic growth rate nudging 10 percent, Kazakhstan is also becoming a magnet for job-seekers from the rest of Central Asia and beyond. Oil and gas workers from Europe, the US

and Australia flock to the port cities of Aktau and Atyrau on the Caspian Sea. Construction laborers from Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan propel building booms in Almaty and the capital, Astana. Turkish architects whip up million-dollar Italianate villas in the Almaty foot-hills for the nouveau riche, and other wealthy Kazakhs invest in towering apartment blocks, even though many units remain unsold.

“The reason there’s so much construction is because there’s hardly anywhere else but real estate to park your money,” explains Ablet Kamalov, a historian who runs educational exchange programs with universities in Europe and the US. How long this bubble will last is the object of intense speculation, he says, adding that so far there are no signs of a softening of the market. Property values in Almaty have quadrupled in four years, he notes, with houses selling for upward of $5000 per square meter (around $450 a square foot)—comparable to San Francisco prices. That a traditionally nomadic people should have caught real-estate fever is just one more irony of the new Silk Roads.

With his shaggy black hair, open sports shirt and jeans, the 46-year-old former Rockefeller Fellow at the US Library of Congress cuts a casual figure in the downtown offices of his non-profit organization for educational reform, Bilim–Central Asia. Kazakhstan, like other Central Asian countries, is trying to shake off authoritarian Soviet teaching methods in favor of western models that encourage student-teacher dialogue and independent thinking, says Kamalov. Schools are gradually shifting to instruction in Kazakh, abandoning Russian. Textbooks are undergoing major revisions, particularly in history where, for example, the Soviet conquest of Central Asia is no longer portrayed positively.

What goes begging, however, are engineering, scientific-research and teaching posts, not just in Kazakhstan, but all across Central Asia. The independent governments have abandoned the high levels of support once provided by the former Soviet Union and, as a result, academics have lost prestige as well as funding. Medical doctors in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, for instance, earn around $50 a month, according to Khorlan Ismailova, health specialist with the Almaty office of USAID. In Tajikistan, it’s only five dollars a month.

Almaty’s art scene is also struggling for lack of money. Seven years ago, in 2000, there were 20 contemporary art galleries. Now there are three—including an impressive space opened by car dealer Nurlan Smurgalov and sited somewhat incongruously next to his Toyota showroom on the six-lane road to the airport. Yet despite the lack of galleries, it’s not all grim, says 43-year-old painter Marat Bekeyev, who points out that the number of Kazakh collectors is growing with local wealth. “A few years ago, the 20 or so full-time artists in Almaty were all concerned with getting shown abroad, but now we’re able to sell most of our work locally,” he explains.

Europe and the US still hold the key to international recognition for Central Asian artists, however, and many are represented by galleries from Berlin to Milwaukee. Like a latter-day Marco Polo, curator Yuliya Sorokina, 42, brought Central Asia to Venice, presenting avant-garde works by 21 regional artists at the 2007 Venice Biennale. Sorokina, a woman of irrepressible energy who trained in arts management in Vienna and Salzburg, remains optimistic. “People here are oriented to the West, so if we get attention abroad, they sit up and take notice,” Sorokina remarks. Earlier this year, she mounted a collaborative exhibition mingling Central Asian and British artists that showed in Manchester, London and Almaty.

Central Asian cinema is another reflection of changing tastes along the new Silk Roads. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, according to movie critic Gulnara Abikeyeva, “local directors are turning away from Russia and more toward Asia. Kazakh movies are close to Chinese cinema, Uzbekistan films are like India’s, and the few new Tajik films look Iranian.” A tireless champion of regional cinema, Abikeyeva organized September’s Eurasian Festival in Almaty that showcased some 70 films in a weeklong program.

A recent spate of historical movies attempts to exalt the Kazakh national myths and heroes suppressed during the Soviet era. The $37-million epic “Nomad,” released in 2005, was a glorification of Kazakh heritage that The New York Times compared to a John Ford western. Although Kazakh films—there are 22 currently in production—win festival prizes around the world, Abikeyeva complains that they’re almost never distributed inside the country, except for a few airing on television.

Televisions are much on my mind when I land in Tashkent after a two-hour flight from Almaty.

Passing through Uzbekistan customs, it seems as if every other passenger is pushing a large, flat-screen TV. A couple of days later, I discover why.

Walking down Navoi Street, a tree-shaded thoroughfare with a tramway running down the middle, I happen on a sprawling electronics and appliance market that stretches for a mile or more. It proves an eye-opening update on the latest trading patterns in this ancient Silk Roads city. Rows of shops are filled with televisions, home-theater systems, computers and office furniture. Outside, the street is lined with a bewildering array of Korean refrigerators, Chinese air conditioners, Russian washing machines and Byelorussian ovens. Salesmen have set up computers at desks on the street, and they are playing music over loudspeakers. I stop in one electronics store and find that a Panasonic television with a 127-centimeter (52") screen sells for $5000—far more than the price outside the country. No wonder customs was jammed with them. In Uzbekistan, where college professors earn $100 a month and many people work one or two extra jobs to supplement $50 monthly wages, I wonder who could afford such extravagances—much less the $12,000 and $24,000 automobiles manufactured inside Uzbekistan by Daewoo. I later learn from Kamal Asya, the Turkish ambassador, that individual Uzbeks annually import some $1 billion of goods from Turkey, mostly textiles, food and appliances—yet another lucrative link, by truck, air and rail, along the new Silk Roads.

Like Almaty, Tashkent too is minting a new bourgeoisie and not a few plutocrats. Lavish mansions, complete with crenellated walls and pointy-roofed turrets, sprout in some precincts. Even though these pleasure domes are modeled on the châteaux of the Loire and princely Czech residences, they are generically dubbed “Mickey palaces” after the castle at Disneyland.

Built on the second- or first-century BC site of Ming-Uruk (“A Thousand Apricot Trees”), Tashkent, whose 11th-century name means “City of Stone,” is the most populous city in Central Asia, with around 4.5 million inhabitants in a country of 27 million. A major caravan junction in AD 751, when it was conquered by Arab Muslims, Tashkent is now divided into two sections: a Russian one, with broad boulevards, grandiose marble government edifices, parks and fountains, built mostly after the 1966 earthquake, and the older Uzbek neighborhoods with one- and two-story courtyard homes and bazaars that survived the massive temblor, which registered 7.5 on the Richter scale.

During the communist era, Uzbekistan was known as the most progressive country in Central Asia, attracting immigrants from other Soviet republics to the relative freedom of its intellectual and cultural life, especially in Tashkent. Today it’s still the most culturally active city in Central Asia, with a lively arts scene in theater, music, painting, dance and design.

But its heavily state-controlled economy, which depends on cotton as its main export, is now considerably weaker than that of its oil-rich northern neighbor. “In terms of foreign markets, we’re even behind Afghanistan— although our economy is much bigger overall,” complains Erkin Makhmudov, Moscow-trained chairman of the economics department at the University of World Economy and Diplomacy.

Makhmudov admits that, 15 years ago, he knew little about western economies. “After the collapse of the Soviet Union, my colleagues and I bought marketing texts in the US and UK and taught directly from them at first,” he recalls. “Gradually, we started producing our own texts.” Makhmudov also journeyed to the University of Oklahoma with a group of students to study western educational systems, and

he has since welcomed Oklahoma professors and undergraduates to Tashkent, where he teaches them about Central Asian history and economy.

One of Makhmudov’s former students later spent time in Europe with his father analyzing restaurant design and operation. After a few months, they returned to Tashkent and recently opened J. Smokers, which has become a wildly successful knock-off of a British pub.

“It’s just one example of how a rising generation of entrepreneurs can stay in Uzbekistan and create private businesses that work,” Makhmudov maintains. In a far-flung expansion of the trade in ideas, it’s also tangible proof of the way Central Asia can now reach far afield for a trendy marketing concept.

While new restaurants and cafés spring up across the city, Tashkent’s 20 or so theaters—the number is equivalent to Moscow’s—are among the region’s busiest. One popular children’s venue recently staged Molière’s “Les Fourberies de Scapin” in Uzbek. Only one, however—the experimental Ilkhom Theater—boasts a truly international reputation, having toured London, Seattle, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Jerusalem and Moscow and earned plaudits that compared the troupe to the Maly Theater in St. Petersburg, Peter Brook’s Bouffes du Nord in Paris and Berlin’s Schaubühne. Founded in 1976 by the late Tashkent-born Mark Weil, the fiercely iconoclastic Ilkhom (“Inspirations” in Uzbek) is one of only a handful of private theaters in Central Asia. It refuses government subsidies on principle. Weil produced plays about political dissent and homosexuality, thinly veiled political attacks on Uzbekistan’s president, Islam Karimov, and works by Aeschylus, Chekhov and Albee.

“You know, I really was crazy,” Weil reflected, smiling about defying the censors during the Soviet era. “Thank God, perestroika came and saved me.”

I spoke with the director at the theater’s café, where actors, audiences and students at Ilkhom’s acting school gather for animated discussions in a surrealist décor—small tables and chairs are attached upside down to the ceiling, with lamps, books, cups and ashtrays glued to the tabletops—a visual metaphor, perhaps, for the way Ilkhom seeks to upend convention and conventional perspectives. A compact, engaging character in his mid-50’s, Weil flitted from table to table, greeting friends and playgoers with his elfin grin and offhand humor.

“People are always amazed to find an experimental theater in Tashkent, but there’s an openness and tolerance in this city that runs very deep,” Weil declared. Tragically, three months after our interview, in early September, Weil was attacked and fatally stabbed by two men in the lobby of his apartment building. Despite much speculation that the attack was political, cultural or sectarian (Weil was Jewish), no suspects have been arrested. He died hours before the season premiere of “The Oresteia,” and his last words were, “I open a new season tomorrow, and everything must happen.” Though with a heartbroken cast, the play did indeed open, and Ilkhom continued its season under deputy artistic director Boris Gafurov; a US tour in March and April of 2008 is still planned.

There are other culture creators in Tashkent, too: Among the most prolific organizations is the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, which produces art, music, dance, film, video installations, photographic exhibitions and books on a shoestring budget of around $250,000 a year. One concert, later released on DVD, brought together Iranian musicians now living in Bukhara. In Tashkent, an annual documentary film festival and a separate labo- ratory workshop for theater and film directors draw participants from all over the region. A series of radio programs focuses on celebratory feasts by some of the country’s 100 different ethnic groups.

“Our purpose is to help Uzbek culture survive without the level of government funding it had during Soviet times,” explains Barno Turgonova, chief cultural officer for the Swiss agency and a Tashkent native. “It’s a long process to find our identity after the breakup of the Soviet Union. Through arts, we can help people cultivate their democratic conscience and pluralism.”

The emphasis on nurturing national identity is all well and good, argues producer-director Ovlyakuli Khodjakuli. “But our writers end up focusing too much on Uzbek heroes like Amir Timur [Tamerlane] and Mirzo Ulugh Beg [Timurid astronomer-ruler] instead of contemporary issues that really engage them.”

With wispy braids making punctuation marks on his chin and shaven head, the 48-year-old director spent a year developing Rap-Shee, a hypercharged blend of local rap performers singing and dancing with traditionalist bakhshi, singer-narrators of the dastan, the Central Asian historical epics told in poetry and music. Sponsored by the Swiss agency, Rap-Shee toured Uzbekistan in the spring of 2006.

Edvard Rtveladze, a renowned historian and archeologist, also questions the rush by independent Central Asian countries to assert separate identities. His concern is that it can foster what he terms “ethnic exceptionalism,” falsely pitting one country against another. “Each population claims it’s the most ancient, the most Asian, the most authentic,” he argues, “but in reality it’s impossible to separate them.

“My biggest fear is that the countries of Central Asia will dissolve into fierce competition economically and politically,” he warns. “We desperately need to generate more intensive cross-cultural contacts.” As in Kazakhstan, the Russian language is in retreat in Uzbekistan, its role as unifier of ethnic groups outweighed by the freight of its colonialist origins. The country has gone so far as to abandon the Cyrillic alphabet: The Uzbek language now appears in Roman characters. This linguistic curveball has had a chilling effect on literacy, because most older Uzbeks now find they cannot read current works in their own language, and there are few books or bookstores.

Yet with more than 150 years of shared linguistic, historic and cultural connections, Russia will remain an indelible influence on Uzbekistan, in the view of many observers. “The current generation is very pragmatic,” argues journalist Boris Golender. “They look to move to places where they can make the most money—Russia and Kazakhstan. They go away for one or two years, come back, then go away again.

“Russia will be an important economic and cultural partner for decades, far more than China or India,” he insists. I reflect on Golender’s comments as I listen to professors and students at the Tashkent Conservatory render a heartfelt musical homage to Mstislav Rostropovich, the Russian cellist and conductor who passed away in April 2007, and again later during three days of celebrations to honor the 19th-century Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. It’s clear that Russian culture retains a tenacious hold on the local imagination, even in the face of an insistent push for Uzbekification.

But if there’s one place in Tashkent where Uzbek tradition still reigns supreme, just as it did in the epoch of the livestock-powered Silk Roads, it’s the bustling, seemingly timeless Chorzu bazaar. Under the massive turquoise dome covering the spice and food market, eager vendors proffer samples from mounds of chili powder, cumin, coriander, nutmeg, paprika and cardamom seeds. Women with sharp Mongolian features chat with one another behind heaps of dates, pistachios and raisins, thumb-sized balls of yoghurt and rock crystals of sugar that gleam amber in the slanting sunlight. Next to stands groaning with small green and red apples, pears, bananas, carrots and cassava, a butcher in white skullcap straddles a stool, ready to carve from a slab of meat in a cloth-covered basket before him.

But even here in the bazaar, where merchants hawk produce as they have for more than a millennium, the 21st-century transformation is inescapable —especially the intrusion of factory goods from China. Down a flight of steps, closer to the Friday Mosque, tables and stalls overflow with the manufactured output of Shanghai and Shenzen—shirts, leather sandals, knock-off sneakers, purses, jewelry, watches, giant stuffed pink bears and stacks of mass-produced bowls festooned with ceramic grapes.

Exiting, I take the number eight tram to the end of the line and emerge into a quiet, leafy suburb of low, pastel-colored houses surrounding enclosed courtyards. Kids play ball in the well-kept but rutted lanes lined with apple, plum and birch trees. After wandering a few of the streets, I catch the tram back into the city. On the way, I notice a woman fastidiously sweeping the ground beneath the high portal that marks the entrance to the Oq Masjid mahallah, one of the many distinct neighborhoods that make up the Muslim part of Tashkent. Civic pride in one’s mahallah, the focus of family and religious life, is a constant that knits Uzbek society together. The tram rumbles past a column of cherry trees so close that the branches slap the windows. Although the outbound trip slipped by quickly, we’re returning at a crawl, for some reason, lumbering forward so deliberately I can count the orange carnations growing along the rails. The car grinds along at about the speed of a fully laden camel, and it occurs to me how quickly you can leave the teeming urban center behind, both physically and mentally. Souped-up Almaty may be supercharged for the Silk Roads of the future, but Tashkent, like this tram, is taking its own sweet time.

Remembering Mark Weil Remembering Mark Weil

I only spoke with him a couple of times, but like many, I felt an immediate and deep rapport with Mark Weil. Later, while writing this article, he and I exchanged a few e-mails about bringing Ilkhom to perform in France, where I live. He had a marvelous wit and an uncanny knack for putting people at ease—social skills exceeded only by his commitment to world-class theater in Tashkent, thousands of kilometers from better-established theater capitals. Both of these qualities inspired immense loyalty and respect from his actors and audiences alike. The extended professional family of Ilkhom is determined to honor Weil’s legacy by continuing Ilkhom’s courage on stage. www.remembermark.com

—R.C. |

Graduation in Kyrgyzstan

Mirlan Osmonaliev, the 32-year-old principal of the Aga Khan School in the Central Asian city of Osh in southern Kyrgyzstan, was stumped. Ordinarily well-behaved

students were turning the cafeteria into a free-for-all, cutting into line, making a racket and leaving trays in a mess on the tables.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

“This was their notion of what you do in a democracy,” the principal explains as teachers come and go in his spacious office. “But they were confusing democracy with anarchy.” After all, the Kyrgyz Republic itself, which was established only in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union, is a year younger than most of the 17- and 18-year-old members of the school’s first graduating class, which celebrated jubilant commencement ceremonies last May.

Osmonaliev came up with a radical solution. Instead of ordering students to stay in line and bus their own plates, he convened all 490 pupils into a general assembly and charged them with drawing up their own rules. Not only did the students, sixth through 12th graders, decide to keep order in cafeteria lines and require that food trays be returned to the counter, they voted to ban all fighting throughout the school, strictly punish tardiness and severely reprimand kids who interrupted conversations.

“Their own self-discipline worked better than anything we adminstrators and teachers could have imposed,” the principal declares with a broad grin.

The five-year-old school in Osh is one of around 300 schools and educational programs throughout Central Asia, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa created by the non-denominational Aga Khan Development Network. Founded in 1966 by the Aga Khan, the leader of the Ismaili Muslim community, the network is a private international organization of cultural, economic, humanitarian and pedagogical initiatives. The Aga Khan network is particularly active in former Soviet republics along the old Silk Routes, and it is currently laying the groundwork for the University of Central Asia, a visionary project with campuses in three countries—Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan—that are scheduled to open in 2012.

Situated in the Ferghana valley a few miles south of the border with Uzbekistan, Osh is Kyrgyzstan’s second-largest city, after its capital, Bishkek. It was chosen as the site for the school because of the need for quality secondary schools in the region. Recent graduation ceremonies were like nothing this provincial burg had ever seen.

|

| RICHARD COVINGTON |

Gathering inside the large courtyard of the airy, three-story tan brick building, invited representatives from the European Union, Germany, the United Nations and the Aga Khan network joined the town’s mayor and other officials in congratulating the 39 graduates of the class of 2007. Surrounded by pink, white and green bunting of the school’s colors, two troupes of young dancers, fetchingly dressed in traditional folk costumes, gave exuberant performances. Not to be outdone, a trio of budding, 14-year-old stand-up comics, pink shirt-tails hanging out of their pants, cracked jokes, spun out rapid-fire rap lyrics and cavorted goofily to the loud applause of parents, teachers and students. Just before handing out diplomas, 17-year-old couples, elegant in black dresses and crisp white shirts, gracefully danced a series of choreographed waltzes. One of the teachers lofted a balloon emblazoned with the school’s banner. It looked for a time like he didn’t want to let the carefully painted creation go. But, he finally set it free, and the balloon floated skyward—an apt metaphor for the ambitious spirits of the graduates themselves.

After the ceremony, I spoke with a group of students, all of whom spoke near-perfect English. (Although classes are given in both Russian and Kyrgyz, English is the most popular foreign language.) Their maturity was sobering.

Oopinionated and disarmingly self-assured at 17, Dinara Batyrova is determined to study abroad, perhaps in Europe or the US, but she is equally committed to returning to Kyrgyzstan to become a lawyer. “Our country has a new constitution and needs good lawyers to help govern,” she explains. Last year, Batyrova was among 21 teenage journalists who learned how to use the Internet to hone investigative reporting skills. The program in Osh was sponsored by the US State Department. She credits the Aga Khan school with giving students freedom. “The teachers respect the students and train us to acquire information to discuss issues rather than arguing or fighting over them,” she says, already sounding much like an aspiring lawyer.

|

| Aga Khan Development Network |

When I ask Batyrova what she would change about the country’s educational system, the group erupts in unison. “Corruption in the universities!” they declare. “Many professors demand money for good grades and this has got to stop,” adds Batyrova.

Like Batyrova, 16-year-old Maksat Kursantbek is aiming high. He’s set his sights on becoming an ambassador, and he speaks enthusiastically of Kyrgyzstan’s largely untapped tourism potential. The most serious in the group, 18-year-old graduating senior Dastan Mamasaliev, plans a career in finance, “to help rebuild the economy,” he volunteers. Meerim Nazarova, 16, also intends to go into business, but she chafes at the enduring inequality between men and women in Kyrgyz society. “Women can’t travel around as freely as men,” she complains, “and I’m determined to change that.” Hearing the conviction in her voice, it’s not hard to imagine she will succeed.

|

|

Paris-based author Richard Covington writes about culture, history and science for Smithsonian, The International Herald Tribune, U.S. News & World Report and the London Sunday Times. His e-mail is richardpeacecovington@gmail.com. |

|

Kevin Bubriski (www.kevinbubriski.com) is a documentary photographer who lives in southern Vermont. His solo exhibition “Nepal Photographs: 1975–2005” recently showed at the Rubin Museum in New York City. |