We’re victims of circumstance who have been lied to, lied about and led astray. Our gang never meant to hurt any human (at least no human who can’t remember the world before the Iron Age), and even then just the daggers and axes among us. Mostly we’re just a bunch of pretty little things that wouldn’t even harm a Hittite. Look at us, Your Honor: Don’t we deserve a second chance, like that old codger obelisk and that cheeky scrap of pottery you’ve been listening to lately? Their tall tales and crackpot stories don’t begin to testify to the sort of misery we’ve suffered.

Why? All because we of the Syndicate are royal treasures from the wrong Troy—as if that’s our fault. Were we ever naïve! We knew no better until it was too late to save the Syndicate from aiding and abetting archeological crime. To plead our case, we call our first witness. He can tell you how we got into this trouble.

er Honor, we all got “made” a long time ago. I was the first one the Boss signed up, back on May 31, 1873, in Turkey. He called me “The Shield.” I’m bronze, and I’m in bad shape, I know: not much to look at as treasures go. I don’t talk so good —my lower lip, see, is all busted up—but I’m the biggest, and the Boss’s number one, so I get to tell the first part of our story.

er Honor, we all got “made” a long time ago. I was the first one the Boss signed up, back on May 31, 1873, in Turkey. He called me “The Shield.” I’m bronze, and I’m in bad shape, I know: not much to look at as treasures go. I don’t talk so good —my lower lip, see, is all busted up—but I’m the biggest, and the Boss’s number one, so I get to tell the first part of our story.

Back in our hometown of Hisarlık, the Boss set up shop and muscled out the competition, which was this guy named Frank Calvert. Frank owned most of the place, and he said it was valuable because a big war happened there once, on account of some dame named Helen. He said Hisarlık was just an alias for “Ilium,” and Ilium was an alias for Troy. That’s how come the dame’s last name was “Of Troy” and not “Of Hisarlık.” I ain’t sure it matters much: She wasn’t a local girl anyways. She was stolen from some heavy hitters over in Greece who got hot about it and mobbed up to get even with the family that grabbed her. Some say she was a cheating flirt who brought it on herself; others say she was just a victim—like us in the Syndicate.

Either way, she was quite the looker, and that’s why there was all the fuss. They measured beauty back then on this funny ship-scale, and they say her face was worth a thousand!

Then this guy Homer—no last name—wrote a coupla long songs about the war, and they were hits for, I don’t know, seems like a jillion years. I’m sure a smart judge like you has heard of the Iliad and the Odyssey, all about these pro gangstas whacking each other and bragging about all the bloodshed. This one mug, Achilles, he could drop a dozen guys before breakfast. Old King Priam, the Trojan don, had to watch his favorite son Hector get popped on account of his other son Paris, the one that kidnapped Ms. Of Troy in the first place. Another guy, Odysseus, he kind of reminds us of us: He spent 10 years in the wind after all the fighting and then—look out—he sneaked home and killed all the goons trying to move in on his wife, Penelope. The Boss always talked about these folks like they was friends of his and he was just dropping by the neighborhood for a chat about old times.

Truth is, before the Boss came visiting, we didn’t know nothing about the Trojan War, and we never laid eyes on Helen nor any of the thugs fighting over her. It was the Boss who made us say we did. He took credit for everything that Frank knew already, and it was the Boss who decided to make himself famous—he was already rich—as the genius who dug up the dirt about Troy. He wanted to show how it all had gone down just the way Homer sung it. That old Greek, the Boss said, was humming history, and our job in the Syndicate was to back up the Boss in case nobody wanted to believe him and Homer.

But this is what really happened: There we were at Hisarlık, a.k.a. Troy, a bunch of unsuspecting locals living in ruins, minding our own business, sinking lower and lower in the world, like we had for centuries. I was in real deep the day the Boss showed up and smacked me with a shovel —bam! That rung my ears a bit, and then he came after me with a big knife. He called our little get-together “archeology,” but to me it felt like a mugging. Behind me, the Boss spotted some of our golden boys and went after them, too. Since he’s one of them, I’ll let my pal “Gravy Boat” testify about that part.

our Honor, the famous Syndicate organized on that day owes a lot to me: I’m as ritzy as my name suggests, not to mention polished and refined—24-carat gold, to be precise. I neither look nor speak much like my long-time partner, “The Frying Pan.” Yes, I know he still fancies himself “The Shield,” but in spite of what the Boss thought him to be, everyone now knows the fellow is a dented kitchen skillet. He’s a simple, honest soul even if he’s not (as they say) all there. The Boss found him in pieces and never put him together properly. While searching for riches and weapons from the Trojan War, he thought it sounded a lot better to be finding some hero’s shield than a pan with a broken handle. The latter pieces, the Boss in turn fantasized, could be seen as the hasps of a disintegrated wooden treasure chest that had allegedly protected valuables like me. So, the Boss dreamed up his colorful Trojan War scenario in which this supposed coffer and its carrier’s shield were abandoned beside the burning walls at the moment the city fell. A grand tale it was, and he christened the Syndicate “King Priam’s Treasure,” which was either a terrible mistake or a shameful lie, depending upon your estimation of the Boss as either a sloppy archeologist or a slippery con. Either way, we in the Syndicate were made guilty of helping to deceive a lot of people for a long time. I’m sorry to say that we played right along and kept to our code of silence. That’s why “Frying Pan” ended up a fugitive with me in Moscow, while his handle is still hiding out in two pieces—one in St. Petersburg, the other in Berlin. We’ve been in serious trouble since the day we were found.

our Honor, the famous Syndicate organized on that day owes a lot to me: I’m as ritzy as my name suggests, not to mention polished and refined—24-carat gold, to be precise. I neither look nor speak much like my long-time partner, “The Frying Pan.” Yes, I know he still fancies himself “The Shield,” but in spite of what the Boss thought him to be, everyone now knows the fellow is a dented kitchen skillet. He’s a simple, honest soul even if he’s not (as they say) all there. The Boss found him in pieces and never put him together properly. While searching for riches and weapons from the Trojan War, he thought it sounded a lot better to be finding some hero’s shield than a pan with a broken handle. The latter pieces, the Boss in turn fantasized, could be seen as the hasps of a disintegrated wooden treasure chest that had allegedly protected valuables like me. So, the Boss dreamed up his colorful Trojan War scenario in which this supposed coffer and its carrier’s shield were abandoned beside the burning walls at the moment the city fell. A grand tale it was, and he christened the Syndicate “King Priam’s Treasure,” which was either a terrible mistake or a shameful lie, depending upon your estimation of the Boss as either a sloppy archeologist or a slippery con. Either way, we in the Syndicate were made guilty of helping to deceive a lot of people for a long time. I’m sorry to say that we played right along and kept to our code of silence. That’s why “Frying Pan” ended up a fugitive with me in Moscow, while his handle is still hiding out in two pieces—one in St. Petersburg, the other in Berlin. We’ve been in serious trouble since the day we were found.

The Boss, of course, had his own name, one of the most celebrated of his time: Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann. He was born in 1822 and he lived until 1890. He was an impressive, self-made type who overcame scandal and tragedy to become a millionaire, a world traveler, a scholar, a prolific writer and—what concerns us—a self-proclaimed discoverer of lost civilizations. A hero to emperors, kings and commoners worldwide, he set out to find us, and, boy, he sure was determined he would find us. Too bad we weren’t quite where and when and what he wanted us to be.

But we’re not fakes. We are indeed genuine treasures, indeed from Troy, and Schliemann—I’ll call the Boss that now—did prove that the city Homer sang about really existed, right where Mr. Calvert told him to look. He made invaluable contributions to history, but unfortunately he also lied about his life and work in order to hide his flaws and make his achievements seem greater than they were. I think today you call this “hype.”

If so, we are the worst examples. Schliemann was desperate to find evidence of the rich city of Priam that, according to Homer, was sacked by the Greeks sometime around 1200 BC. The discovery of “Frying Pan” and the rest of us on the last morning of May 1873 allegedly locked up Schliemann’s case and right away made him the most famous archeologist in the world. People loved his romantic story of Priam’s treasure chest filled with the fabulous wealth that included me and lots of other gold, silver and bronze—9000 of us artifacts in the full Syndicate. Among us was even, he said, the very jewels worn by Helen of Troy herself. Well, you choose whether to believe him or not.

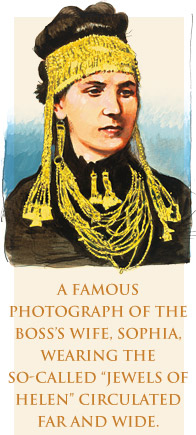

With bravado, Schliemann enumerated to his fans all the mortal dangers he had faced, how he had had to send away his helpers at the last moment to save us artifacts from possible treachery, and how he secretly dug us out with only the help of his young wife, Sophia, who used her shawl to smuggle us away as he passed each object to her. It all sounded too good to be true—and it was! Sophia was nowhere in Turkey at the time of our excavation, and Schliemann later fudged the date and circumstances of the discovery, misrepresented the actual find spot and even doctored his diary to cover his tracks. To him, it seemed that the truth meant about as much as the dirt we were buried in.

All the while, we treasures sure enjoyed the attention. We dared not admit to the world that we had absolutely nothing to do with Priam or Helen. All of us were much too old! We hail from the early Bronze Age, from the emporium of Troy circa 2400 BC. That was five cities, risen and fallen, before the 1200 BC of Homer’s Priam and Helen. So if an army of Greeks did indeed attack Troy, and if a big wooden horse ever really did roll into town, we missed that spectacle, having already been underground for more than a millennium. Schliemann making us pretend otherwise was like asking relics of Charlemagne to pose as witnesses to World War II.

“Frying Pan” and some of the boys would still like to believe that Schliemann made an honest mistake about our age, and that the rest was a web of little white lies to please the public. They say archeology in the 19th century tended to be more sensation than science. In that case, so what if we were really unearthed inside, outside, or on an ancient wall? Who should care if Mrs. Schliemann was actually there or not? Does it matter if we came out of the ground on June 7—as he states in his diary—or a week earlier—as he also states in his diary?

Your Honor, I appreciate now that it does matter. You see, in archeology you only get one chance. The Syndicate will never outlive those lapses of judgment.  We will never be fully trusted again, never valued for what we are without feeling your disappointment for what we are not. Once a defendant like me is held in archeological contempt, judges and juries never forget, and they seldom forgive. I wish we could go back and be discovered differently.

We will never be fully trusted again, never valued for what we are without feeling your disappointment for what we are not. Once a defendant like me is held in archeological contempt, judges and juries never forget, and they seldom forgive. I wish we could go back and be discovered differently.

By the standards of archeology today, Schliemann at the very least turned error into crime. He twisted important facts and tainted one of the finest gatherings of artifacts ever found. He criminalized us time and time again by changing his story. More seriously, he put us at odds with not just the professional standards of archeology, but also the laws of modern nations. Schliemann not only gave us a false identity, but he also smuggled us away. He worked in Turkey under an agreement that guaranteed his host country half of all artifacts recovered. Instead of honoring the agreement, Schliemann tricked the Turkish overseer at Hisarlık and pirated us away in six sealed trunks and one heavy bag aboard the Greek ship Taxiarches. In Athens, Schliemann gleefully unpacked and displayed our stunning selves at his home, where delighted crowds flocked to see the exhibition. A famous photograph of Sophia wearing the so-called “Jewels of Helen” circulated far and wide, and on August 5, Schliemann published in a German newspaper his first dramatic account of our discovery. The world was immediately mesmerized, although some quickly frowned at his shameless subterfuges. Frank Calvert tried in vain to garner the credit he deserved, and naturally the government of Turkey took Schliemann to court. We were wanted fugitives.

Schliemann retaliated with defiant threats to sell “his” collection—that was a good one!—to various institutions, including the Louvre and the British Museum. When that failed, he explored the possibility of making copies of us, then surrendering the fakes to Turkish authorities while keeping the originals. In 1874, a court tried to seize the treasures, but he had craftily sent us into hiding. He paid a hefty fine for this, but then he turned around and offered Turkey five times that sum for purchase of the whole Syndicate outright. The frustrated Turks accepted the deal in 1875—or so Schliemann later claimed in his memoirs.

We came out of our hideouts and we settled into the vaults of the Greek National Bank while Schliemann—now our owner—returned to his unorthodox archeology. In 1877, he sent us to London where we thrilled another adoring public. By then, however, we were growing jealous of his latest finds at Mycenae in Greece, considered by some experts to be more splendid than any of us from Troy. The Mycenaean artifacts set off another global frenzy of what has been called “Schliemania.” Then, in 1878, he returned to Troy in search of greater glories. Was that even possible? We lived on edge, debating what he might unearth next, and then arguing over what he meant when he published an enigmatic promise to leave us to “the nation I love and esteem most.”

At first, most of us thought he must be referring to Greece, the homeland of his wife, Sophia. Others suggested Russia, where Schliemann had lived from 1846 to1866 and made his commercial fortune. But also possible were France, Britain and even the United States, where Schliemann had once gained citizenship to more easily divorce his first wife, who was Russian. Only Turkey seemed off-limits. By the end of 1880, we had our answer: It was Germany—in exchange for a bevy of ego-flattering titles and honors. During the next year, Schliemann arranged us to his liking in the new ethnographic museum of Berlin.

While in German custody, we in the Syndicate of Troy did our time, with good behavior, until the rise of the Nazis. We could hear their rallies right outside the walls. Surrounded by an angry hive of buildings that headquartered the Gestapo and the SS, we knew war was coming. On September 2, 1941, our Syndicate buried itself deep in a concrete bunker of the Berlin Zoo, surrounded by bombproof walls and booming anti-aircraft guns. With every concussion, we longed for the heavy silence of our centuries underground, back home in Hisarlık. While all around us elephants, giraffes and other exotic inmates perished from weapons no Trojan warrior ever imagined, we endured until the battered city of Berlin fell in 1945. It was then we vanished.

While in German custody, we in the Syndicate of Troy did our time, with good behavior, until the rise of the Nazis. We could hear their rallies right outside the walls. Surrounded by an angry hive of buildings that headquartered the Gestapo and the SS, we knew war was coming. On September 2, 1941, our Syndicate buried itself deep in a concrete bunker of the Berlin Zoo, surrounded by bombproof walls and booming anti-aircraft guns. With every concussion, we longed for the heavy silence of our centuries underground, back home in Hisarlık. While all around us elephants, giraffes and other exotic inmates perished from weapons no Trojan warrior ever imagined, we endured until the battered city of Berlin fell in 1945. It was then we vanished.

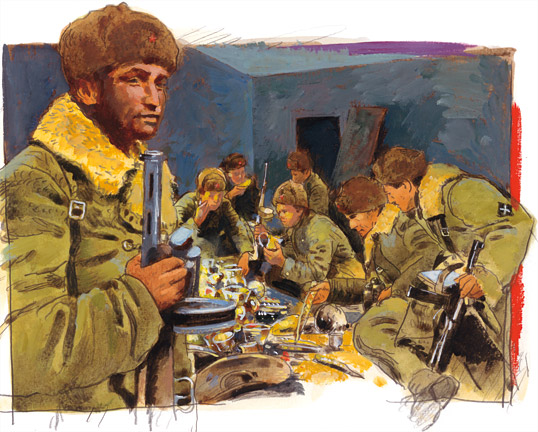

top the proceedings right there, Yer Honor! I ought to tell this last part, because I think the Boss would want it that way. Maybe I am just a frying pan and maybe I ain’t, but I sure felt like a shield during all that fighting. Anyways, we were all hunkered down to wait out the war when a bunch of soldiers broke in and nabbed us. Turns out these fellows was one gang in a big army trying to beat Mr. Hitler who called himself something that sounded like “Furor,” and we were hiding right nearby when eternity grabbed him and shook hands. Then, like the Greeks in Homer’s song, the soldiers that busted into Berlin had their share of disagreements among themselves. They did a lot of chest-thumping, fist-waving and finger-pointing. When it came time to loot the place, one crew grabbed this, another that. In all the confusion, me and old Gravy Boat and the rest of the Syndicate dropped clean out of sight. Word was we got destroyed.

top the proceedings right there, Yer Honor! I ought to tell this last part, because I think the Boss would want it that way. Maybe I am just a frying pan and maybe I ain’t, but I sure felt like a shield during all that fighting. Anyways, we were all hunkered down to wait out the war when a bunch of soldiers broke in and nabbed us. Turns out these fellows was one gang in a big army trying to beat Mr. Hitler who called himself something that sounded like “Furor,” and we were hiding right nearby when eternity grabbed him and shook hands. Then, like the Greeks in Homer’s song, the soldiers that busted into Berlin had their share of disagreements among themselves. They did a lot of chest-thumping, fist-waving and finger-pointing. When it came time to loot the place, one crew grabbed this, another that. In all the confusion, me and old Gravy Boat and the rest of the Syndicate dropped clean out of sight. Word was we got destroyed.

It took about 50 years for everybody to figure we made it out alive, and where we went. As I said, a gang named the “Reds” arrested us and carried us to a prison in Moscow called the Pushkin Museum. Nobody was the wiser until 1991, when a coupla sharp Russian sleuths found us out. They spilled the beans and the whole world showed up to gawk at us like it was 1873 all over again. Too bad Homer wasn’t around to sing about it, but I hear his grandson Mr. TV kind of took up his trade and told a fine story about us. We’re now what you call jailbird celebrities, waiting in your court of public opinion to see if we stay in Russia or get extradited to Germany, Greece or Turkey.

Well, Yer Honor, that’s our story, from one end of history to the other. We spent the biggest part of it down under, sleeping with the dishes of dead Trojans and waiting for the Boss to find us. Fact is, when me and the gang first went underground at Troy, your obelisk wasn’t even born; he was just part of a big rock over in Egypt. He wasn’t a stand-up guy for another thousand years. Later, we kept right on dozing underfoot at Hisarlık during all his traveling days. For every week of his life he was lost and buried, we spent a month waiting for sunlight. If you think that obelisk served a long sentence before his pardon, I guess we suffered through a whole paragraph. That young obelisk was up again and strutting in his new piazza 284 years before the Boss ever dug us up. And that day didn’t improve our situation much, because we’ve been on trial ever since.

You might think it’s a good thing being wanted. You might say we ought to feel grateful we were flushed from hiding in Hisarlık, Athens, Berlin and Moscow. But you’re only human. We in the Syndicate see it different. Getting found doesn’t mean you ain’t still lost to the world, and being treasures from Troy ain’t enough for some people unless maybe you fried an egg for Priam and poured some gravy for Helen.

Yer Honor, we’ve learned this the long, hard way. We’re sorry for all the trouble. Begging your mercy, we confess that we were never there at the Trojan War, and we sure found out for ourselves what Ms. Of Troy must have felt like with her reputation ruined and all those nations fighting over her.

So what do you say? Bang that gavel, and let us go home. We promise we’ll never do it again.

|

Frank L. Holt (fholt@uh.edu) is a professor of history at the University of Houston and most recently author of Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan (2005) and Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions (2003), both published by the University of California Press.

|

|

Norman MacDonald (www.macdonaldart.net) is a Canadian free-lance artist, living in Amsterdam, who specializes in history and portraiture. This is the third article he has illustrated in the “I Witness History” series.

|