have watched the sun rise over the Aegean world nearly 900,000 times, and I shall never tire of the joy. Rosy-fingered dawn creases the darkness and, with a firm handhold on the sky, pulls up the day from behind the hills to set my city aglow. Here and there, a silly young rooster thinks the sun has risen just to hear him crow, but I know the light has come to see me. It plays among my mighty columns and seeks out the museums of weathered art still hidden among my clothes. Hour by hour, sunshine shoves against shadow and makes my features move: Prancing horses come to life amid the figures of men and mythological monsters embroidered in stone about me. What the night had chilled becomes warm and alive, and my marble dazzles the Aegean day like no other monument ever made. Granted, I am not all that I once was, but what age has stolen, the sun still remembers, and I forgive. Perhaps a lady should never say so, but nothing ever built by human hands impresses me more than ... me. I am the temple of Athena, mistress of the Acropolis—the incomparable Parthenon.

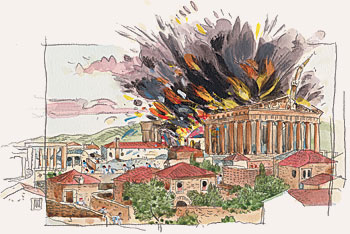

You, the Children of Now, can appreciate my storied birth among the Children of Then. They were angry and afraid as they gathered here at what you might call the “ground zero of the Greek Golden Age,” sorting through piles of ash and rubble in the aftermath of the Persian attack that had torched the city and toppled even its religious monuments high on this Acropolis. Tradition tells us that the Greeks swore an oath never to rebuild what had been wrecked on sacred ground, vowing instead to leave the site empty as a silent memorial for generations to come. When their grief abated, however, they abandoned their oath, and they healed the wounded spot with a monument worthy of their resilient civilization—and so I was born.

I am what you might call an octastyle peripteral Doric temple with a hexa-style double-prostyle cella housing a chryselephantine statue. That’s architectural shorthand for a plain-style Greek temple with eight columns at each end and 17 down each side, enclosing two walled chambers with six columns in front of each and more colonnades inside, all surrounded by sculptural decoration and sheltering a gigantic cult statue fashioned of ivory and gold. No Greek temple ever dressed itself more elaborately in sculpture than I. Massive figures embellished my pediments: the story of Athena’s birth portrayed at the east end, and the struggle for Attica between Athena and her uncle Poseidon on the west. Above my architrave on all four sides, a series of 92 sculptured panels, or metopes, presented in high relief a miscellany of mythical battles involving Amazons, centaurs, gods and giants. Most famous of all (but for all the wrong reasons, thanks to Lord Elgin), a continuous low-relief frieze wrapped 160 meters (520') around me, tucked high up in the shadows between my colonnades. This marvel depicted a grand religious procession animated by more than 200 cavalrymen, musicians, offering-bearers, deities, sacrificial animals and suppliants of both sexes and all ages. These figures probably represent the Panathenaic Procession that honored Athena every year.

The most incredible of my sculptures stood 13 meters (42') from floor to ceiling inside my main room, or cella. Glistening in gold and ivory, this statue of Athena showed that she was no demure little deity, but rather a woman of war-like mien. The master sculptor Pheidias decked her out in a triple-crested helmet and armed her with a towering spear and a sturdy shield.

She wore a dazzling robe and had a monstrous snake curled at her feet. I still recall the gasps of visitors when they crossed the threshold and saw her looming ahead. Imagine their shock to see Athena so large that she held in her outstretched palm a figure of the winged goddess Nike (“Victory”) that itself stood much taller than a man.

Crown of the Acropolis, everything about me was meant to glorify Athena and her namesake city. I am the largest Doric temple ever completed by the Greeks, and the only one built entirely of marble. I may not look massive, but I am a big girl. Just three of my 46 exterior columns weigh more than that entire Egyptian obelisk in the Piazza del Popolo of Rome.  Pound for pound, my exquisitely proportioned body could absorb 88 such obelisks with stone to spare. He is tall, stark and handsome, but he is no match for my subtle curves and fashionable accessories. (See “Beauty Secrets of the Parthenon,” page 41.) Among history’s honor roll of engineering wonders, I carry my weight quite well. Art imitates not only life, but also legend. The Greeks liked to believe that Athena was miraculously born full-grown from the head of her father, Zeus. Ironically, I came into the world with similar dispatch. Annual construction records, written in stone for public scrutiny, allow you Children of Now to reconstruct just how—and how fast— I was built by the Children of Then. Given the intricacy of the project; the diversity of the craftsmen; the tonnage of marble to be chiseled, hauled and hoisted; the necessary bureaucratic oversight; and the working conditions on the cramped heights of the Acropolis, it might seem a miracle that I was ever completed at all, much less so immaculately. But even to the ancients, the most amazing part of the whole process was its speed. I grew from ground to grandame in just 15 years, between 447 and 433 BC. You Children of Now fancy the phrase, “quick as a New York minute,” but even in your modern Manhattan the Cathedral of St. John the Divine is only two-thirds finished after 116 years. In that length of time, I had already experienced adult-hood long enough to see my city rise from its ashes to enjoy world power, fall horribly at the hands of the grim-faced Spartans, rise again with a new democracy and succumb once more when the kings of Macedonia came this way.

Pound for pound, my exquisitely proportioned body could absorb 88 such obelisks with stone to spare. He is tall, stark and handsome, but he is no match for my subtle curves and fashionable accessories. (See “Beauty Secrets of the Parthenon,” page 41.) Among history’s honor roll of engineering wonders, I carry my weight quite well. Art imitates not only life, but also legend. The Greeks liked to believe that Athena was miraculously born full-grown from the head of her father, Zeus. Ironically, I came into the world with similar dispatch. Annual construction records, written in stone for public scrutiny, allow you Children of Now to reconstruct just how—and how fast— I was built by the Children of Then. Given the intricacy of the project; the diversity of the craftsmen; the tonnage of marble to be chiseled, hauled and hoisted; the necessary bureaucratic oversight; and the working conditions on the cramped heights of the Acropolis, it might seem a miracle that I was ever completed at all, much less so immaculately. But even to the ancients, the most amazing part of the whole process was its speed. I grew from ground to grandame in just 15 years, between 447 and 433 BC. You Children of Now fancy the phrase, “quick as a New York minute,” but even in your modern Manhattan the Cathedral of St. John the Divine is only two-thirds finished after 116 years. In that length of time, I had already experienced adult-hood long enough to see my city rise from its ashes to enjoy world power, fall horribly at the hands of the grim-faced Spartans, rise again with a new democracy and succumb once more when the kings of Macedonia came this way.

I remember all of this very well for, in many cases, I collected timely little keepsakes, just as you might on a smaller scale assemble a scrapbook or memory-box. Shields and weapons from famous battles hung on my walls or lay stored away in the treasure chamber at my western end. This particular compartment was called the Parthenon (“Maiden’s Bedroom”), and by this name I became generally known. There the jewelry of Alexander the Great’s Asian wife Roxane competed for shelf space with piles of precious coins from distant cities, victory wreaths from generals, furniture from foreign palaces, and artwork from nearly everywhere. A staff of priestly accountants kept inventories of these mementos and offerings, which included so many luxurious objects that I occasionally lent the Athenians money or other valuables during times of financial crisis. If you had the contents of Fort Knox and the Smithsonian stashed in your basement, you would have some inkling of what I accumulated over the years.

Of course, any lady as lovely and wealthy as I must guard against the attentions of unworthy men. When I was 144 years old, a dissolute Macedonian tyrant named Demetrius Poliorcetes (“the City-Sacker”) beguiled the Athenians and settled himself among my treasures, living there in a fashion that defiled the goddess I was meant to dignify. A few years later, his rival Lachares did worse: To pay off his mercenaries, he stole from the statue of Athena the golden robe given her by Pheidias. Then came the Romans, whose nutty emperor Nero drilled into my eastern architrave a cluster of deep holes, which held in place the metal letters of a pompous inscription advertising his imagined virtues. It is one thing to put messages on a blimp or a city bus, quite another to screw a billboard onto the Parthenon. The embarrassing words are now gone, but the wound remains on my face.

Yet that pain cannot compare with the anguish caused by a fire set by invaders when I was about 700 years old. The flames devoured my treasures, destroyed my 350-ton roof and disfigured my body from skin to skeleton. I thank the Romans that repairs were made, though not to the standards of my original construction. Grafts and transplants from nearby buildings served my healers as makeshift remedies.

In this way, I recovered enough to remain functional as Athena’s most famous temple.

That career ended before I turned a thousand years old. The signs of religious change were evident everywhere in the Greco-Roman world, and as readily as pagans became Christians, their temples became churches. So I bid farewell to the virgin Athena and embraced the Virgin Mary; baptistery replaced treasury; congregants filled my main cella for the first time. (The interiors of pagan temples were not used for assembly.) An apse closed off my eastern doorway, and much of my sculpture was painfully removed or scraped down into innocuous stumps. Fortunately, my long Panathenaic frieze proved less odious to Christians than the Amazons, centaurs and such on my metopes, so Athena’s procession survived my transformation from Parthenon into Our Lady of Athens cathedral. Back in the days when medieval was modern, I served the shrunken community of Athens as best I could. Sadly, the city had faded far into the background of the Byzantine Empire, Rome’s successor in the East. I resumed my hobby of collecting mementos, though the fashion of the day brought me more skulls and finger-bones of various saints than captured shields of Persian warriors. Churchgoers, from the poorest artisan to the proudest archbishop, left little messages carved into my columns and walls, a graffiti chronicle that historians now treasure. In this unusual archive can be traced the ebb and flow of my middle-aged life, when I frequently passed through the hands of rival families, some Catholic and others Orthodox. I echoed with not only changing liturgies, but languages as well: Latin, Greek, French and Spanish, depending upon whose wedding or funeral I observed.

As an ecumenical center of worship, I had devoted half my life to paganism and half to Christian sects when, at the age of 1900, I found another faith: Islam. Under the patronage of Sultan Mehmed II, conqueror of Constantinople, I became a mosque, and for centuries a slender minaret soared above my marble. During the 17th century, the Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi published one of the most poetic appraisals ever made of my enduring beauty. He concluded with a fervent prayer that I, “a work less of human hands than of Heaven itself, should remain standing for all time.” It was a lovely sentiment, but just a few years later, I was all but annihilated in the worst moment of my life.

The trauma occurred on the evening of September 26, 1687. A well-armed band of Venetian invaders surrounded the Acropolis, intent on capturing these historic heights from the Turks. I had been watching scraps like this for 2100 years, but lately with more trepidation: Swords and spears had given way to cannon. I winced as the Venetians trained their sights on me. As the Turks huddled for safety inside me, more than 700 cannonballs found their mark against my marble. But not only people sheltered here: So did their stores of gunpowder—until a Venetian volley crashed through my roof and exploded the Turkish magazine. There was nothing I could do. Three hundred souls perished, and to this day I have not recovered from the shock. My roofing and interior rooms vanished in the maelstrom, as did many of my columns. Only a shell of me remained amid the marble debris.

Some of the bomb-rubble was salvaged to rebuild the mosque, which can be plainly seen in the earliest surviving photographs taken of me. The rest lay in heaps that invited tourists and townspeople to help themselves. With some bitterness, I must say that a few takers went too far, most infamously the seventh earl of Elgin.

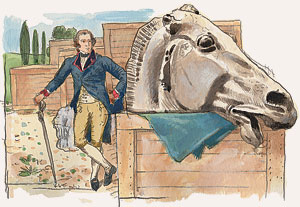

As Great Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Lord Elgin seized upon every opportunity to ship back home a personal harvest of plundered Greek antiquities. In 1801, his agents began their assault on Athens armed with an official Turkish firman that permitted them to … well, who really knows? The document may have authorized the collection of some exploded sculptural fragments yet scattered at my feet, or perhaps it gave license to gather certain inscriptions: In any event, Elgin interpreted the grant to include anything he wanted on the ground or still on me. For months his team tore at my flesh, removing 15 metopes, 17 large figures from my pediments and more than 75 meters (240') of the Panathenaic frieze. Many contemporaries deplored this outrage, including Lord Byron, whose poetry vilified Elgin. Vital parts of me went to Britain nonetheless, and there they remain, still at the center of argument and acrimony. Some say Elgin rescued what the Turks—or air pollution—would otherwise have completely destroyed; others coined the French term elginisme along the same lines as the English word “vandalism,” which originally described what the Vandal invaders did to Rome. Flayed to adorn Elgin’s countryhouse, I am hardly a neutral party in this dispute. True, my marbles (please do not ask me to call them Elgin’s) now reside in the stately British Museum, but that is only because the cash-strapped lord eventually sold them. To whom do they rightfully belong? Britain? Greece? Humanity? No, they belong to me! I have no doubt they will return someday, and that I shall weep to see them as though I had been given back all my youth and half my beauty.

Of course, it is only fair to say that I have been mugged and mutilated by others as well. Through one means or another, parts of me have ended up in Paris, Rome, Munich, Palermo, Strasbourg, Vienna, Washington, Copenhagen, Heidelberg and other places far from the Acropolis. I’m thankful that I have been more or less protected, over the past 175 years, by a most attentive cadre of guardians who call themselves archeologists. They have pored over my broken and buried pieces, attempting wherever possible to puzzle me back together. Such efforts have awakened the world once more to my place at the forefront of art and engineering. Architects have studied my refinements and declared me the most important, the most perfect building ever created. At their insistence, I became a fashion model at the mature age of 2300. Children of Now can scarcely visit a modern city and not see an homage to me: banks, museums, mansions and courthouses all trying desperately to capture my classic good looks. There is even a full-scale concrete replica—complete with a copy of Pheidias’s gigantic statue of Athena—in Nashville, Tennessee.

Meanwhile, I keep my joyful vigil over the Athens of my birth. Worshipers of a new kind throng the Acropolis, but some things never change. The Children of Now, like the Children of Then, still puff up the steep pathway and pause reverently before me, raising a salute to shield their eyes against the greatest of my admirers—the Aegean sun.

Beauty Secrets of

the Parthenon

Good looks like mine do not come easy … or cheap. My body was mined, ton by precious ton, from the finest marble of Mt. Pentelicon. Every one of many thousands of monumental pieces, no two the same, was custom-quarried to fit into its singular place, often with tolerances of less than 1/20 of a millimeter (two thousandths of an inch). Many of my surviving joints are so precise that they cannot be examined except under strong magnification. Each nine-ton Doric capital took workers two full months to cut from the quarry, and days more to transport the hilly 10 miles from Pentelicon to the building site. Besides masons and sculptors, my beauty depended on the talents of many trades, including some you might easily overlook: rope-makers, riggers, road-builders, sledgers, scaffolding carpenters, gilders, painters, muleteers, water-fetchers and so forth. Some were freemen, others slaves, but all labored side-by-side and drew decent salaries from the public payroll. Look at me carefully: Can you tell where the sculpting done by a slave ends and that of his master begins? I did not think so—my beauty is classic, my artistry classless.

Those in charge of my upbringing (the famous Pheidias, Ictinus and Callicrates) took great pains that I grew properly. Even now, I look gorgeously straight and symmetrical only because I am not. My columns seem to taper gracefully from the bottom up, but they appear so only because they actually swell two centimeters (3⁄4'') in the middle; the Greeks called this trick entasis. Those same columns lean inward or else they would not appear perpendicular at all: If extended upward, they would converge some 5000 meters (16,250') above me. My corner columns are more closely spaced and have to be thicker in order to look like all the others. The platform on which I rise bulges upward in the middle on all four sides so that it seems to be perfectly flat. If erected without these subtle adjustments, I would look a mess, with sagging waist and feeble limbs, giving me the graceless posture of a Surinam toad. My ingenious designers understood these optical challenges and how, very precisely, to compensate for the many failings of the human eye. My visual perfection is what you might today call a “virtual reality.”

|

Frank L. Holt (fholt@uh.edu) is a professor of history at the University of Houston and most recently author of Into the Land of Bones: Alexander the Great in Afghanistan (2005) and Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions (2003), both published by the University of California Press. |

|

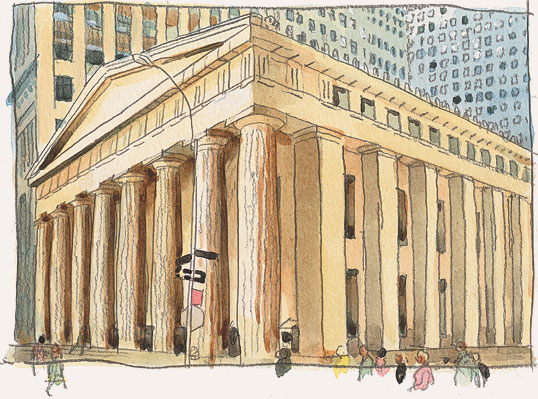

Norman MacDonald (www.macdonaldart.net) is a Canadian free-lance artist, living in Amsterdam, who specializes in history and portraiture. This is the fourth article he has illustrated in the “I Witness History” series. |