|

|

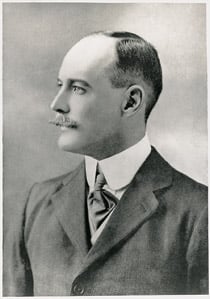

| Captain William Henry Irvine Shakespear, 1878–1915. Born in Bombay, he was a highly visible personality with a deep interest in desert ways. |

he “journey which is proposed” was an ambitious one: a crossing of the Arabian Peninsula, from Kuwait to the Red Sea, with a substantial side trip into the central regions. The traveler was ambitious, too, as well as experienced. He was Captain William Henry Irvine Shakespear— soldier by training; diplomat by profession; amateur photographer, botanist and geographer by inclination; and adventurer at heart. Along his way, he would meet again with the ruler of central Arabia, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa‘ud.

he “journey which is proposed” was an ambitious one: a crossing of the Arabian Peninsula, from Kuwait to the Red Sea, with a substantial side trip into the central regions. The traveler was ambitious, too, as well as experienced. He was Captain William Henry Irvine Shakespear— soldier by training; diplomat by profession; amateur photographer, botanist and geographer by inclination; and adventurer at heart. Along his way, he would meet again with the ruler of central Arabia, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa‘ud.

When the Foreign Office cable approving the journey arrived, Shakespear was nearing the end of a five-year posting as Britain’s political agent in Kuwait. He had already made several journeys into the Arabian interior, and with leave coming due, he had lobbied persistently to make this trip, his longest expedition to date— indeed, he had offered to finance it from his own pocket. The Foreign Office’s reluctance was political: Shakespear’s relations with ‘Abd al- ‘Aziz, known in the West as Ibn Saud, threatened to rankle the Ottoman Turks, who held part of the Gulf coast of Arabia. ‘Abd al-‘Aziz sought to expel them; the British sought their favor, the better to shore up British regional interests. Turkish control was on the wane from the Adriatic to the Caspian, and Russia, France, Germany and Britain all sought to fill the power vacuum they left.

Shakespear had already met the future king of Saudi Arabia on four occasions. The first was in March of 1910 in Kuwait, a year after Shakespear took up his post. Under Shaykh Mubarak al-Sabah, Kuwait was free of direct Turkish control, making it a kind of strategic cockpit from which the British could view and assess the flux of regional rivalries. It was a significant posting for Shakespear, who at the time of his appointment was only 30 years old.

Their subsequent meetings were in ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s own domains, and they marked the ruler’s first encounters with a westerner. The friendship and respect that developed between the two men formed the basis of the modern relationship between Britain and Saudi Arabia, and helped lay a foundation for the favorable reception of subsequent British emissaries, most notably H. St. John Philby. Although Shakespear’s name and exploits remain a legend around Kuwait and Najd and within the Al Sa‘ud family, he remains virtually unknown in his homeland.

Shakespear was born in Bombay, India, where he grew up speaking both English and Punjabi. In the decade after his 1897 graduation from Sandhurst, the Royal Military College, Shakespear served in the Devonshire Regiment and the Bengal Lancers of the Indian Army. There he learned Urdu, Pushtu, Farsi and Arabic well enough to be credentialed as an interpreter in each. As an assistant district officer back in Bombay, he led a rat-extermination program that stanched a plague outbreak that had killed some half a million people. For this, he received commendations from the governor of Bombay, which brought him to the attention of the viceroy; the viceroy’s office transferred him to the Indian Political Department, which also oversaw British interests in the Persian and Arab worlds.

Posted next to Bandar Abbas, on the Strait of Hormuz, Shakespear served as consul under the political resident in Abu Shayr, Major (later Sir) Percy Cox. At age 25, Second Lieutenant Shakespear was the youngest consul in the Indian administration. He brought with him to Bandar Abbas a sextant and a ponderous, glass-plate camera, fitted with a clockwork mechanism that allowed it to take panoramic pictures. Both instruments served him well on his later Arabian sojourns.

In 1907, on his first home leave, he made the journey to England not by ship but overland, traveling through Persia, Turkey and Europe in a new, eight-horsepower, single-cylinder Rover motorcar, purchased from a Karachi dealer for £250. He was among the first to drive this route, and his success prepared him for more challenging, less mechanized, expeditions later.

It was after this leave that Shakespear received his Kuwait assignment. Full of energy, he was a highly visible personality. He imported his car and was soon driving it into the desert. He often captained the British Agency’s launch into the Arabian Gulf, in all weathers. He took up falconry, and he used a camera that required the plates to be developed on site, often in a white tent with an annexed, lighttight bathroom-cum-darkroom. He took a deep interest in desert ways and almost immediately began planning journeys to the interior. “Shakespear came like a whirlwind,” says Victor Winstone, whose Captain Shakespear (1976, Jonathan Cape) remains the only biography of the man.

Although his relations with Shaykh Mubarak began badly over matters of local policy and the shaykh’s general skepticism of British intentions, Winstone tells how a firm friendship grew between them nonetheless. “And out of their understanding,” he wrote, “came the close comradeship of the Englishman and the hereditary ruler of Central Arabia,” ‘Abd al-‘Aziz— for it was Shaykh Mubarak who had given refuge to ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s father.

In his first sojourns south and west of Kuwait, Shakespear began to learn the ways of the land and the Bedouin tribes. He was an accomplished horse and camel rider and an expert shot. He acquired a saluki pack in addition to his falcon. He enjoyed his own company and spent much of his spare time keeping his diary, recording “fixes” of his position, sketching, mapping or developing photographs. When on his desert expeditions he wore his military uniform and pith helmet. Only once in all of his trans-Arabian journeys, when fearing attack from Turks and hostile tribesmen near Aqaba, did he don Arab clothes.

|

In this draft of his letter to King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Al Sa‘ud, written at the conclusion of his 111- day 1914 journey, Shakespear reiterated his gratitude “for all the efforts and kindness which your amirs evinced for my affairs.” He also warned the king of Turkish rifle shipments to the rival Al Rashid in Hail, and promised to send, as soon as he could find one, a barometer with Arabic markings. |

Winstone recalls visiting Bedouin in Kuwait in the 1970’s who told “remarkable campfire tales of the English ‘gonsool skaykh-speer,’ as they pronounced it….” One Arab he met had a particularly vivid tale: He had contracted smallpox and was left in the desert to die or survive, as God willed. Shakespear visited him and took him food. Among these men in Kuwait, Shakespear was still remembered for such deeds.

His first encounter with ‘Abd al- ‘Aziz had come the night Shakespear returned from a 1600-kilometer (1000-mi) expedition south of Kuwait, marred by the shooting death of his trusted rafiq (attendant) in a raid near what is today Hafar al-Batin in Saudi Arabia. Shakespear’s record of that meeting is the earliest report of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz through European eyes: He was “a fair, handsome man, considerably above average Arab height with a particularly frank and open face, and after initial reserve…of genial and very courteous manner.” The next day, Shakespear laid on a meal for Shaykh Mubarak and his Najdi guests, which included roast local lamb accompanied by such British touches as mint sauce, asparagus and roast potatoes.

Shakespear records that ‘Abd al- ‘Aziz was surprised by his knowledge of the desert and his grasp of Najdi Arabic, gained in just one year in his post. “He offered me a welcome should I ever contemplate a tour so far afield as Riyadh.” Later, the ruler of Najd agreed to Shakespear’s request to photograph him along with Shaykh Mubarak, and his plate camera then captured the first known photographs of the future founder of Saudi Arabia.

bdullah Ibrahim al-Askar, a history professor at King Sa‘ud University in Riyadh, has specialized in researching oral history in Najd, including the stories that surround the name of Shakespear. Al-Askar’s own grandfather, while amir of the town of Majma‘ah, met Shakespear twice, first in Kuwait and then in 1913 in Majma‘ah.

bdullah Ibrahim al-Askar, a history professor at King Sa‘ud University in Riyadh, has specialized in researching oral history in Najd, including the stories that surround the name of Shakespear. Al-Askar’s own grandfather, while amir of the town of Majma‘ah, met Shakespear twice, first in Kuwait and then in 1913 in Majma‘ah.

“My grandfather received Shakespear as a friend, and they spent an evening in the majlis [reception room] drinking coffee and smoking,” al-Askar recounts. “He arranged for townsmen to escort Shakespear to ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s spring camp at Khafs Oasis, some 100 kilometers [60 mi] south. There, he stayed with ‘Abd al-‘Aziz for four days. Their meetings in spring weather and open desert pastures strengthened their personal relationship.”

According to al-Askar, the presentday collective memory of the visit is that Shakespear received a traditional and open welcome. “For an outsider to stay at the camp of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was a special honor, and rumors abounded,” he says. “The locals believed that something political was cooking, although people still do not understand what was spoken of, and perhaps agreed upon, there.”

Shakespear did not record his conversations, but his official reports argued the need to recognize ‘Abd al- ‘Aziz as the rising, dominant element in the region, the only one with the widespread support and capacity to drive out Turkish influence. This was not what the British wanted to hear, occupied as they were with delicate negotiations with their Turkish allies over Central Arabia and the Gulf: They preferred a stance of neutrality and non-intervention.

But by mid-1913 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, without any British support, had succeeded in driving the Turks from al- Hasa and winning control of the eastern shore of the Arabian Gulf as far north as the border of Kuwait. The British were forced to take him more seriously, and Shakespear’s next meeting with ‘Abd al-‘Aziz was an official one, held in December at the Gulf port of ‘Uqayr. The topic was the prospect of a treaty with Britain.

When Shakespear returned to Kuwait, he continued preparations for his expedition across the Arabian Peninsula. In a letter to the Foreign Secretary in Simla, he argued that he would collect valuable data and survey unmapped territory. “After all, the whole of the risk and expense is mine, while government stands to get all the profit and benefit of the results,” he wrote. In a private covering note to his immediate superior, Sir Percy Cox, he called the letter “my last despairing effort re my trip to Central Arabia,” and promised Cox that “of course I shall be careful to avoid all politics in my trip and really all I want is a hint from Foreign that they have no objection to the trip as a geographical effort.”

His efforts paid off. Shakespear set out on Tuesday, February 3, first along his previous route to Majma‘ah, and then turned toward Riyadh, where ‘Abd al-‘Aziz greeted him warmly. Shakespear’s diary records the meeting just hours after halting from what had already been a five-week journey. “Tea, coffee and sweets and talk until the evening prayer and then again afterwards until nearly 9.30 when I came back, escorted as before to camp and dinner. Finished sketching, write up this, and…so to bed,” he wrote. Later, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz pressed Shakespear for an arrangement with Britain, but Shakespear exchanged letters with ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and continued to press the British Foreign Office with his conviction that the Najdi ruler would soon head an independent Arabia.

“Shakespear’s trans-Arabian journey covered about 1200 miles [1950 km] of unknown country,” wrote Douglas Carruthers, an Arabian explorer whose 1922 account for the Royal Geographical Society, “Shakespear’s Last Journey,” was, until Winstone’s biography, the only published account of the expedition. “For the whole distance of 1810 miles [about 3000 km], Shakespear kept up a continuous route-traverse, checked at intervals by observations for latitude. He also took, as on his previous journeys, hypsometric readings for altitude, which give a most useful string of heights between the Gulf and the Hijaz Railway.”

Within months, these data were being used by the War Office’s geographical department, and Shakespear’s collection of pressed plants was in the hands of the Natural History Museum, “in many instances the first of their kind to find their way to a western museum,” wrote Winstone. “They remain as evidence of his wide-ranging scientific curiosity and his thoroughness as an explorer.” Politically, Shakespear was more prescient than successful: Despite his final reports, Shakespear failed to convince the Foreign Office that the Turks were doomed in Arabia.

With the outbreak of World War I, Shakespear returned to Kuwait as a political officer on special deputation to ‘Abd al-‘Aziz. Turkey’s alliance with Germany meant that Britain was now pressing for ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s cooperation in removing the Turkish presence from Basra, in southern Iraq, in return for the treaty ‘Abd al-‘Aziz had long sought, which would recognize him as the independent ruler of Najd.

Shakespear joined up with ‘Abd al-‘Aziz near Majma‘ah at the end of 1915 and began discussions on a draft treaty. He remained with the ruler as he moved farther north to Jarab with his army of more than 6000 townsfolk and Bedouin, who were preparing to face not the Turks, but the forces of Ibn Rashid, rival contender for Najd. Neither side emerged from this battle a clear victor.

Shakespear’s last letter to his brother tells of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz’s concern for his safety, suggesting perhaps the Englishman’s inability to recognize the changing nature of tribal desert warfare, which had grown more lethal as the Great Powers provided increasingly sophisticated weapons. “‘Abd al-‘Aziz wants me to clear out but I really want to see the show and I don’t think it will be unsafe really….”

Shakespear also refused ‘Abd al- ‘Aziz’s request that, if he would not leave, he at least wear Arab dress, in order not to be conspicuous in his British uniform. Undaunted, Shakespear took his camera and stationed himself near a Saudi field gunner. He was then wounded in the thigh. As the charging Shammar horsemen of Ibn Rashid came nearer, he refused to leave his position. According to the gunner, who survived, Shakespear “fell fighting” on the battlefield at Jarab.

hortly after Shakespear’s death, the fulcrum of British influence in Arabia shifted west from the India administration to the Cairobased Arab Bureau. With this shift, wrote Philby, “it was left to [T. E.] Lawrence and the army of the Hijaz to accomplish what in other circumstances might have been accomplished by ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and Shakespear.” Another British commander (and later author), Sir John Glubb, wrote that “when I was on a mission in 1928 to ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, I heard him say with emphasis that Captain Shakespear was the greatest Englishman he had ever known.”

hortly after Shakespear’s death, the fulcrum of British influence in Arabia shifted west from the India administration to the Cairobased Arab Bureau. With this shift, wrote Philby, “it was left to [T. E.] Lawrence and the army of the Hijaz to accomplish what in other circumstances might have been accomplished by ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and Shakespear.” Another British commander (and later author), Sir John Glubb, wrote that “when I was on a mission in 1928 to ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, I heard him say with emphasis that Captain Shakespear was the greatest Englishman he had ever known.”

But by the time Glubb met ‘Abd al- ‘Aziz, stories and images of Lawrence— “Lawrence of Arabia”—had so gripped the imagination of the English-speaking peoples that less vivid and romantic characters such as Shakespear were eclipsed. It was as if, Winstone says, “there was hardly room for another account of wartime adventure or achievement in the eastern theater.”

In recent years, Shakespear’s role in Arabia has come in for more attention from both Britons and Saudis. H. St. John Armitage is a specialist in Middle East affairs and a former British soldier and diplomat with half a century’s experience in Saudi Arabia. He has taken a particular interest in Shakespear’s legacy and, as part of Saudi Arabia’s 1999 centennial celebrations, presented a paper that cited 74 references to unpublished records and pointed to a continuing Saudi interest in Shakespear. “The Saudi–British relationship is based on personal contacts, and the friendship that developed between ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and Shakespear was the start of the relationship,” says Armitage.

Today’s diplomats take a similar view. Sir Derek Plumbly, British ambassador to Saudi Arabia, has read extensively through documents, in both Arabic and English, relating to Shakespear and to later British emissaries who met ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, such as Colonel H.R.P. Dickson, Lt. Colonel R.E.A. Hamilton, Major R.E. Cheesman, Colonel Gerald de Gaury and Sir Gilbert Clayton.

As the first Briton to meet ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, Plumbly says, “Shakespear played a central role in establishing a bond of trust between our two governments, a bond which has lasted over 85 years. Among those who know Saudi Arabia, he is not forgotten, and to those who have worked since in cementing relations between Britain and Saudi Arabia, he remains a hero.”

“Shakespear’s life and involvement in Arabia lasted less than eight years,” says Zahir Othman, “and yet it was intense and filled with remarkable encounters and experiences.” Othman is the director general of Al-Turath, a cultural foundation established by Prince Sultan ibn Salman, a grandson of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz. “He won friendship because he spoke fluent Arabic, respected and learned from the Bedouin and cherished their love of desert pursuits, horsemanship, camel-riding, falconry, poetry, tales around the campfire and the open freedom of the desert.” But what sets him apart to this day, says Othman, who has studied early travelers to Arabia, was Shakespear’s “early and unwavering faith in the leadership of ‘Abd al-‘Aziz and his cause of uniting the country” at a time when others, looking at Arabia only from outside, could not see clearly what was happening inside. For this, says Othman, Shakespear “is not just remembered here, but remembered with affection.”

|

Peter Harrigan works with Saudi Arabian Airlines in Jiddah, where he is also a contributing editor and columnist for Diwaniya, the weekly cultural supplement of the Saudi Gazette. |

This article appeared on pages 26-33 of the Compilation Issue 2008 print edition of Saudi Aramco World.

Check the Public Affairs Digital Image Archive for Compilation Issue 2008 images.