nder cover of darkness, they beached their small, lateen-rigged sailing vessel on the

rocky shore and began the slow, silent climb to the manor house on the hill. Storm clouds shrouded the moon, darkening the coastal

Mediterranean landscape; sporadic rain and gusting winds concealed the sailors’ approach. They were 20 men, armed with daggers and short swords, and clad in the fighting tunics of al-Andalus—Islamic Spain.

nder cover of darkness, they beached their small, lateen-rigged sailing vessel on the

rocky shore and began the slow, silent climb to the manor house on the hill. Storm clouds shrouded the moon, darkening the coastal

Mediterranean landscape; sporadic rain and gusting winds concealed the sailors’ approach. They were 20 men, armed with daggers and short swords, and clad in the fighting tunics of al-Andalus—Islamic Spain.

They climbed carefully, avoiding the brambles that covered the slopes to their left and right. A few lights still burned in the manor house. The Provençal nobleman and his

household had finished the last meal of the day. After listening to the songs of a visiting troubadour, the residents of the manor house were preparing to sleep. But it would not be long before the evening serenity of that coastal villa would be shattered.

This was the opening act in an 85-year drama played out along the coast of Provence in the ninth and 10th centuries of our era. This little-known but significant projection of Arab military power into the land of the Franks was the second of its kind in less than three centuries. The first, launched almost two centuries before, is the one most of us know about. Conducted from al-Andalus by an army on horseback, it was thwarted by Eudes of Aquitaine at Toulouse in 721 and by Charles Martel at Poitiers in 732.

This was the opening act in an 85-year drama played out along the coast of Provence in the ninth and 10th centuries of our era. This little-known but significant projection of Arab military power into the land of the Franks was the second of its kind in less than three centuries. The first, launched almost two centuries before, is the one most of us know about. Conducted from al-Andalus by an army on horseback, it was thwarted by Eudes of Aquitaine at Toulouse in 721 and by Charles Martel at Poitiers in 732.

The second projection, overlooked by most of our history books, began as a small-scale military operation along the beautiful stretch of coastline now known as the French Riviera. Frankish chroniclers, in unabashedly one-sided and hostile accounts, sought to dismiss the operation as a “pirate raid.” It may have appeared so to some at the time. But the passage of time and subsequent events proved these chroniclers wrong. Pirate raids are normally isolated, sporadic events. The operation on the Provençal coast, as we shall see, revealed itself eventually to be an integral part of the foreign policy of the Umayyad caliphate in Spain. The “raid” unfolded into something much more ambitious, giving the forces of al-Andalus, for the better part of a century, effective control of the coastal plain linking France and Italy and of the mountain passes into Switzerland—some of Europe’s most vital trade and communication routes.

Arab chroniclers of the period—that is, those whose works have come down to us—have little to say about this unique occurrence on the Provençal coast. Perhaps they did not regard it as sufficiently important, compared with the momentous events then taking place to the southwest, in the Iberian Peninsula.

At that time, the Umayyad dynasty of al-Andalus, which had ruled Spain for scarcely a century, was being challenged from all directions. Revolts were under way in scores of Spanish cities, some led by Arabs, some by North African Berbers, and others by muwalladun, or Muslims of Spanish stock. The Umayyad amir ‘Abd Allah, an educated, pious man who lacked political skills, struggled desperately to maintain his realm, but by 912 the amirate had virtually disintegrated, and ‘Abd Allah controlled little beyond the walls of his capital, Córdoba.

In that year, he was succeeded by his talented grandson ‘Abd al-Rahman III, who was destined to become one of the greatest leaders in the history of Islamic Spain. Over the coming years, ‘Abd al-Rahman would end the rebellions, establish a caliphate in al-Andalus and preside over a “golden age” of prosperity that saw Córdoba become the leading intellectual and political center of Europe.

All this occurred while Andalusi forces, building on a minor beachhead in Provence, were gradually extending their control into neighboring areas of France, northern Italy and even Switzerland. But if Arab historians are silent, the Europeans left records of the original incursion and its aftershocks, and from them we can reconstruct the story.

One of the most detailed accounts comes from Liudprand of Cremona, a 10th-century Italian cleric and diplomat. He described the 20 men who carried out the Provence operation as “Saracen pirates”; they would have viewed themselves as special forces of the caliphate. Their personal identities are lost to history. E. Lévi-Provençal, perhaps the greatest western historian of al-Andalus, believed such crews were often a mix of Arabs, Berbers, muwalladun and even Christians. They may have acted under specific orders from the Umayyad government at Córdoba; it is also possible they operated with greater freedom and flexibility under the Muslim equivalent of a letter of marque, with official authority to raid Frankish lands. Whatever the case, Liudprand confirms their role as an instrument of Andalusi foreign policy when he informs us that the base they eventually established in southern France operated under the protection of ‘Abd al-Rahman III and in fact paid tribute to him.

The Saracens, as Andalusis and other Arab Muslims were known in those days, were quite sensibly attracted to the Provence region, whose natural beauty and fertility were enhanced by the fact that no kingdom or empire currently ruled it. The Mediterranean coast from Marseilles to Italy, with its rocky headlands and lush, wooded coves, studded with palm trees and brilliantly colored flowers, must have been as alluring to Muslim adventurers of the ninth century as it is to travelers today. Indeed, the 17th-century Arab historian

al-Maqqari related with some amusement the folk belief of an earlier age that the Franks would be barred from Paradise because they had already been blessed by their Creator with a paradise on earth:

fertile lands abounding in fig, chestnut and pistachio trees, amid other natural bounties.

The Saracens established their beachhead on the coast of Provence in about 889, at a time of great confusion and misery. Just 30 years earlier, France’s southern coast had been plundered and

pillaged by Norse pirates. Entire towns had been

leveled and many local inhabitants put to the sword. Duke Boso of Lyons, a usurper related by marriage to France’s ruling Carolingian dynasty, took advantage of the chaos and, with the support of local counts and bishops, set up his own breakaway kingdom in Provence in 879. The Carolingian kings could not evict him. When Boso died in 887, his son and heir, Louis, was too young to rule effectively; local lords and princes began asserting their independence and challenging one another. The Carolingian empire was splitting into western and eastern Frankish kingdoms. There was no central authority along the southern French coast, and Provence was ripe for the plucking.

Saracen naval forces and corsairs struck often along these shores. Just as in later centuries British privateers—pirates—often worked hand-in-glove with the Royal Navy, so Andalusi corsairs plied the western Mediterranean in the sympathetic shadow of a large Saracen naval fleet, built up by the Umayyad government only a few decades before in response to the Norse raids that also struck the coasts of al-Andalus.

The 20 Saracens set sail from a Spanish port or island, apparently intent on a military target in the east. Whether the Gulf of St. Tropez was their primary target cannot be said for certain. According to Liudprand, stormy weather forced them to retreat into the gulf, where they beached the craft without being spotted. The gulf opens toward the east; the present-day fishing port of St. Tropez, fashionable vacation spot of artists, film stars and the well-to-do, is situated on the southern shore. The Saracens landed northwest of there and, drawn by the torch lights of the manor house, headed up the mountain ridge known as the Massif des Maures. Some say the ridge takes its name from the invading Arabs, who were also known as Moors; others claim it derives from a Provençal corruption of the Greek word amauros, meaning “dark” or “gloomy”—an apt description of the mountain’s thick forests of cork oak and chestnut.

Before sunrise, the Andalusis stormed and captured the manor house

and secured the surrounding area. When dawn finally broke, they could see, from the heights of the massif, towering Alpine peaks to the north, undefended but thickly forested slopes below and the broad blue expanse of the Mediterranean to the south.

The Saracens decided to hold their position. They began building stone fortifications on the surrounding heights. As further defense against Frankish attack, Liudprand says, the Arabs encouraged the growth of particularly fierce bramble bushes that proliferated in the area, “even taller and thicker than before, so that now if anyone stumbled against a branch it ran him through like a sharp sword.” Only “one very narrow path” offered access to the Saracens’ fortifications. “If any one gets into this entanglement, he is so impeded by the winding brambles, and so stabbed by the sharp points of the thorns, that he finds it a task of the greatest difficulty either to advance or to retreat,” the cleric wrote in his history, titled Antapodosis, or Tit for Tat.

Their defenses secured, the Andalusis reconnoitered the countryside. They sent messengers back to al-Andalus with word of their success, praising the lands of Provence and making light of the military ability of the local inhabitants. As a result, a new band of about 100 Andalusi fighters, certainly including cavalrymen (fursan) and their mounts, soon arrived from Spain to bolster the original 20.

Many more followed as the Andalusis asserted their military presence in the area and scored victories over scattered Frankish opposition. Administrators and supplies arrived from Córdoba. In time, the Saracen presence along the Riviera grew to such an extent that military expeditions sometimes involved thousands of troops. The Gulf of St. Tropez became a regular port of call for Andalusi naval and cargo ships in the western Mediterranean.

The Saracens called their base Fraxinet (in Arabic, Farakhshanit), after the local village of Fraxinetum, named in Roman times for the ash trees (fraxini) then common in surrounding forests. Today, this village survives as La-Garde-Freinet, a picturesque, unspoiled settlement tucked amid forests of cork oak and chestnut some 400 meters (1300') up in the Massif des Maures, between the Argens Plain and the Gulf of St. Tropez. About a half-hour’s hike up from the village are the ruins of a stone fortress said to be the one built by the original 20 Saracens. Other high points in the area were also fortified by the Andalusis, but local authorities state that nothing remains of those structures.

Gradually, local Frankish lords, seeking to take advantage of the new political and military realities, sought the aid of the Andalusis in settling their private quarrels. The strategy backfired, according to Liudprand: “The people of Provence close by, swayed by envy and mutual jealousy, began to cut one another’s throats, plunder each other’s substance, and do every sort of conceivable mischief.... They called in the help of the aforesaid Saracens...and in company with them proceeded to crush their neighbors.... The Saracens, who in themselves were of insignificant strength, after crushing one faction with the help of the other, increased their own numbers by continual reinforcements from Spain, and soon were attacking everywhere those whom at first they seemed to defend. In the fury of their onslaughts...all the neighborhood began

to tremble.”

Gradually, local Frankish lords, seeking to take advantage of the new political and military realities, sought the aid of the Andalusis in settling their private quarrels. The strategy backfired, according to Liudprand: “The people of Provence close by, swayed by envy and mutual jealousy, began to cut one another’s throats, plunder each other’s substance, and do every sort of conceivable mischief.... They called in the help of the aforesaid Saracens...and in company with them proceeded to crush their neighbors.... The Saracens, who in themselves were of insignificant strength, after crushing one faction with the help of the other, increased their own numbers by continual reinforcements from Spain, and soon were attacking everywhere those whom at first they seemed to defend. In the fury of their onslaughts...all the neighborhood began

to tremble.”

European chroniclers claim that the

Saracens sacked the coastal territory around Fraxinet, today called the Côte des Maures, and then moved into neighboring areas in search of targets. First, pressing eastward, they “visited the county of Fréjus with fire and sword, and sacked the chief town,” according to E. Lévi-Provençal. The town of Fréjus, a major seaport founded by Julius Caesar in 49 BC and given the name Forum Julii, was reportedly razed but its population spared.

The Andalusis drove on, hitting one town after another along the Côte d’Azur. Eventually they looped back to the west, conducted operations against Marseilles and Aix-en-Provence, then headed up the Rhône Valley and into the Alps and Piedmont. Historians believe that North African Berber soldiers, experienced in mountain warfare, were probably used extensively in the Alpine operations. By 906, Andalusi forces had seized the mountain passes of the Dauphiné, crossed Mont Cénis and occupied the valley of the Suse on the Piedmontese frontier. The Saracens erected stone fortresses in areas they conquered—in the Dauphiné, Savoy and Piedmont—often

naming them Fraxinet, after their base. The name survives to this day in these areas in various forms like Fraissinet

or Frainet.

It did not take much longer before the Saracens were able to control direct communications between France and Italy. Pilgrims bound for Rome through such Alpine valleys as the Doire, Stura and Chisone often were forced to turn back in the face of Andalusi military actions. In 911, the bishop of Narbonne, who had been in Rome on urgent church business, was reportedly unable to return to France because the Saracens controlled all the passes in the Alps. By about 933, says Lévi-Provençal, “light columns, very mobile, held—at least during the summer—all the country[side] ... while the bulk of the Muslim forces was entrenched in the mountainous canton of Fraxinetum, in the immediate vicinity of the sea.”

Frankish historical accounts often portray the Saracens as frightening and immensely powerful. For example, 19th-century historian J. T. Reinaud, drawing on the accounts of the period, observes: “One saw ample evidence forthcoming for the oft-repeated saying that one Muslim was enough to put a thousand [Franks] to flight.” This is a strange claim to make about a motley band of “pirates,” as the Frankish historians often described them. The claim makes much more sense if the Saracens were in fact not pirates but rather a large and well-organized military force under the command of a government. As for fearing the Andalusis, those who feared them most were doubtless the clergy of Provençal, who stood to lose their power base if local populations turned to Islam, as had happened

in al-Andalus.

Not all Provençals feared the Andalusis of Fraxinet, however. Some formed alliances with them. “There are...reasons to believe that a number of Christians made common cause with the Muslims and took part in their attacks,” Reinaud notes in his Invasions des Sarrazins en France, et de France en Savoie, en Piémont et en Suisse. If the villagers and townsfolk of Provence and neighboring regions feared the Saracens as much as contemporary chroniclers claim, they somehow managed nonetheless to cooperate with them in a wide range of social, economic and artistic fields.

Not all Provençals feared the Andalusis of Fraxinet, however. Some formed alliances with them. “There are...reasons to believe that a number of Christians made common cause with the Muslims and took part in their attacks,” Reinaud notes in his Invasions des Sarrazins en France, et de France en Savoie, en Piémont et en Suisse. If the villagers and townsfolk of Provence and neighboring regions feared the Saracens as much as contemporary chroniclers claim, they somehow managed nonetheless to cooperate with them in a wide range of social, economic and artistic fields.

The Arabs of Fraxinet were not simply warriors; careful reading of the chronicles reveals that many Andalusi colonists settled peacefully in the villages of Provence. They taught the Franks how to make corks for bottles by stripping the bark every seven years from the cork oaks that proliferate in the forests of the Massif des Maures. Today, the cork industry is the area’s chief local enterprise. The Saracens also showed the Provençals how to produce pine tar from the resin of the maritime pine, and to use the product for caulking boats. Reinaud believes the Umayyads of Córdoba kept a naval fleet permanently based in the Gulf of St. Tropez, in part to facilitate communications throughout the western Mediterranean. The tar of Fraxinet would have been used by those sailors. Today in France, pine tar is called goudron, a word derived from the Arabic qitran, with the same meaning.

The Saracens also taught the villagers medical skills and introduced both ceramic tiles and the tambourine to the area, and Reinaud believes the Arab colony at Fraxinet had a “considerable influence” on the development of local agriculture. Some French scholars believe the Saracens of Fraxinet introduced the cultivation of

buckwheat, a grain that has two names in modern French, blé noir (black wheat) and blé sarrasin (Saracen wheat). Furthermore, strong similarities have been noted between the poetry of the Provençal troubadours and that of Andalusi poets, but this particular case of cross-fertilization may have occurred even earlier than the Arab settlement

of Provence.

We know little of the individuals who directed or took part in this Arab enterprise in France. Rarely are the Saracens of Fraxinet mentioned by name in the European

chronicles of this period. Liudprand tells of one Arab military commander with the Latinized name Sagittus (perhaps Sa‘id) who led an Andalusi fighting force from Fraxinet to Acqui, some 50 kilometers (30 mi) northwest of Genoa. But about all we learn of Sagittus is that he died in battle at Acqui in about 935.

A leader of Fraxinet itself, Nasr ibn

Ahmad, is mentioned in the Muqtabis of Ibn Hayyan of Córdoba, the greatest historian of medieval Spain. According to that 11th-century chronicle, ‘Abd

al-Rahman III made peace in 939-940 with a number of Frankish rulers and sent copies

of the peace treaty to Nasr ibn Ahmad, described as qa‘id, or “commander,” of Farakh shanit, as well as to the Arab governors

of the Balearic Islands and the seaports of

al-Andalus—all of them subject to the Umayyad caliphate. Nothing else is revealed about the Fraxinet commander.

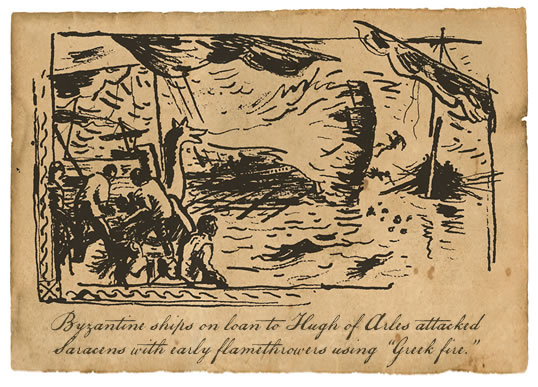

The first serious Frankish effort to expel the Saracens from Fraxinet was made by Hugh of Arles, king of Italy, in about 931. Hugh, seeking control of Provence for

himself, enlisted the aid of Byzantine

warships on loan from his brother-in-law Leo Porphyrogenitus, emperor of Constantinople. The warships, hurling “Greek fire,” attacked and destroyed an Andalusi fleet in the Gulf of St. Tropez. Meanwhile, in a coordinated land assault, Hugh’s army besieged the fortress at Fraxinet and succeeded in breaching its defenses. The Saracen defenders were forced to withdraw to neighboring heights. But just when the end of the Andalusi colony in southern France seemed inevitable, local politics intervened.

Hugh received word that his rival Béranger, then in Germany, was planning a return to France in a bid to capture the throne. The king, desperate for allies, sent the Greek fleet back to Constantinople and formed a hasty alliance with the Saracens he had just sought to expel. He signed a treaty conceding control of Fraxinet and other areas to the Andalusis and stipulating that Arab forces should occupy the Alpine heights—from Mont Genèvre Pass in the west to the Septimer Pass in the east—and block any attempt by Béranger to cross into France. Liudprand, ever hostile to the Saracens, was outraged by Hugh’s actions; in the midst of his chronicles, the historian chides the king: “How strange, indeed, is the manner in which thou defendest thy dominions!”

Hugh received word that his rival Béranger, then in Germany, was planning a return to France in a bid to capture the throne. The king, desperate for allies, sent the Greek fleet back to Constantinople and formed a hasty alliance with the Saracens he had just sought to expel. He signed a treaty conceding control of Fraxinet and other areas to the Andalusis and stipulating that Arab forces should occupy the Alpine heights—from Mont Genèvre Pass in the west to the Septimer Pass in the east—and block any attempt by Béranger to cross into France. Liudprand, ever hostile to the Saracens, was outraged by Hugh’s actions; in the midst of his chronicles, the historian chides the king: “How strange, indeed, is the manner in which thou defendest thy dominions!”

After seizing the Great

St. Bernard and other key Alpine passes, the Andalusi forces spread out into the surrounding valleys. Grenoble and the lush valley of the Graisivaudun were captured in about 945. About 10 years later, Otto I, king of Germany and later Holy Roman Emperor, perhaps fearing the Saracens would score successes in his own realm, sent an envoy to the caliph at Córdoba, ‘Abd

al-Rahman III, urging an end to military operations in the Alps by the Andalusis of Fraxinet.

In the early to mid-960’s, the Saracens began a slow but steady withdrawal from the Alpine regions. To some extent this was due to growing Frankish military pressure, and perhaps to the diplomatic initiatives of Otto I. But one modern scholar, Middle East specialist Manfred W. Wenner, suggests the withdrawal may have been prompted by a foreign-policy change in Córdoba. ‘Abd al-Rahman III died in 961 and was succeeded by his son Hakam II, a peaceful man who did not share his father’s enthusiasm for military operations in southern France and the Alpine regions. Wenner believes Hakam may have “withheld permission for reinforcements to leave for Fraxinetum from Spanish ports,” making it increasingly difficult for the colony to maintain a military presence in the Alps.

By 965, the Andalusis had evacuated Grenoble and the valley of the Graisivaudun under continuing pressure by the troops of various Frankish nobles. The fertile farmlands and prosperous villages they relinquished were divided up among the Frankish forces who replaced them, in proportion to each soldier’s valor and service. According to Reinaud, writing in about 1836, “even today such families of Dauphiné as the Aynards and Montaynards trace the turn of their fortune to this struggle with the Muslims.”

As late as 972, the Saracens still controlled the Great St. Bernard Pass. In that year, they detained a party of travelers that included a political opponent, the famed Frankish cleric Maiolus, abbot of Cluny, who was traveling through the pass on his return from Rome. Maiolus and his large entourage were eventually released, but the incident provoked outrage throughout the Frankish realms and sparked further

efforts to dislodge the Fraxinet colony and its satellites.

Shortly after 972, the Saracens were driven from the heights around the Great St. Bernard. One of the leaders of the opposing forces in this hard-fought battle was Bernard of Menthone, for whom the mountain pass was later named. (Its name at the time was Mons Jovis, Latin for “Mount Jupiter”—a term the Arabs of that era incorporated into their name for the entire Alpine region, Jabal Munjaws.) Bernard, of course, later founded the well-known hospice for travelers in the heights of the Great St. Bernard that exists to this day. Some scholars believe the Maiolus incident furnished the impetus for building that refuge. Bernard’s name, incidentally, was also given to the celebrated dogs trained there to rescue travelers trapped in the winter snows.

Along the Riviera itself, local lords gradually overcame their differences and, in about 975, joined forces with Count William of Arles, later marquis of Provence, in a bid to consolidate all of southern France under his rule. William was a popular leader, and managed to persuade warriors from Provence, the lower Dauphiné and the county of Nice to join his cause against the Saracens.

The Andalusis, realizing the seriousness of the threat being mounted against them, consolidated their forces at Fraxinet and “came down from their mountainous resort in serried ranks,” as Reinaud says, to encounter the Frankish forces at Tourtour, near Draguignan, about 33 kilometers

(20 mi) northwest of Fraxinet. The Saracens were driven back to their mountain stronghold, and the Franks laid siege to the fortress. The Andalusis, realizing their fate was sealed, abandoned the castle in the dark of night and fled into the surrounding woods. Many were either killed or captured by Count William’s forces, according to contemporary accounts, and those who laid down their arms were spared. It is said that the Frankish army also spared the lives of those Andalusi colonists living peacefully in neighboring villages.

Fraxinet had served as the administrative capital of all Saracen settlements in France, northern Italy and Switzerland, and its castle is believed to have held vast quantities of treasure. All the booty from Count William’s conquest was said to have been distributed among his officers and men. His second-in-command, Gibelin de Grimaldi of Genoa—an ancestor of Prince Ranier III, who ruled present-day Monaco until 2005—received the area where the hillside village of Grimaud stands today, overlooking the port of St. Tropez. Ruins of Grimaldi’s feudal castle, built in the Saracen style, still crown the village.

Thus ended the Arab colonization of southern France. Andalusis made later attempts to establish footholds along that coast: They conducted military operations at Antibes in 1003, at Narbonne and Maguelone in 1019 and in the Lérins Islands off Cannes in 1047. But never again were the forces of al-Andalus able to repeat the stunning success of Fraxinet.

Thus ended the Arab colonization of southern France. Andalusis made later attempts to establish footholds along that coast: They conducted military operations at Antibes in 1003, at Narbonne and Maguelone in 1019 and in the Lérins Islands off Cannes in 1047. But never again were the forces of al-Andalus able to repeat the stunning success of Fraxinet.

The mountainous regions of inland Provence are dotted with hundreds of old fortified hill villages, like Grimaud, whose very existence is a reminder of the “Saracen period.” These villages were first built for protection against Saracen raids and later served to protect the Frankish villagers from marauders of their own faith. The peasants lived within their walls, venturing out to work their fields by day. By the 19th century, however, with the establishment of durable peace and order, peasants began leaving the hill villages and moving down into the valleys. Today, some of these villages lie wholly or partially abandoned, but many are being restored, their old stone structures converted into weekend or summer homes for the affluent or housing small colonies of artists and craftsmen. Old mines and remnants of forges at Tende in the Maritime Alps northeast of Monaco and at La Ferrière, near

Barcelonnette, have been identified as sites where Saracens extracted iron ore and

manufactured weapons.

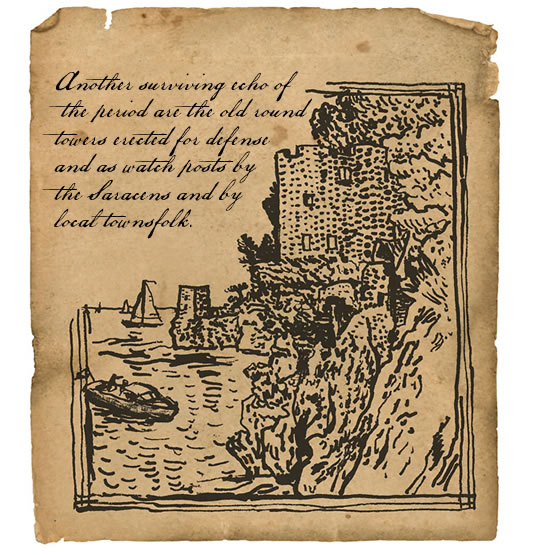

Another surviving echo of the Fraxinet period is the old round towers erected for defense and as watch posts not only by the Saracens but also by local townsfolk. The Frankish towers mimic the style of Arab ones. Ruins of what are called “Saracen

towers” are found all along the coast, as well as in nearby Alpine valleys.

These are the remaining physical traces of the Arabs of Fraxinet: courses of cut stone, jutting from

the underbrush, as fragmentary and mysterious as the tale that underlies them. Beyond this, the Saracens of St. Tropez and their cohorts live on as part of the folk memory of Provence, remembered as soldiers, merchants and agents of change in a dark and troubled era.

| 711 |

Arabs enter Spain. |

| 717 |

Al-Hurr’s army enters France. |

| 721 |

Al-Samh’s forces routed

at Toulouse. |

| 728 |

Andalusi fleet raids Lérins Islands, off Cannes. |

| 732 |

Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi’s forces lose Battle of Tours and Poitiers. |

| 759 |

Franks recapture Narbonne. |

| 827 |

Andalusis launch naval raid on Oye in Brittany. |

| 831 |

Andalusis launch naval attack on Marseilles; sail up estuary of

the Rhône. |

| 848 |

Arles in Saracen hands. |

| 869 |

Andalusis raid Provence and construct a harbor in the Camargue. |

| 889 |

Twenty Andalusis sail up the Gulf of St. Tropez and found a colony at Fraxinet (Farakhshanit). |

| 906 |

Andalusis cross the defiles of the Dauphiné and Mont Cénis. |

| 908 |

Andalusis occupy the valley of

the Suse. |

| 911 |

Andalusis hold the Alpine passes. |

| 920 |

‘Abd al-Rahman, uncle of ‘Abd al-Rahman III, amir of al-Andalus, crosses the Pyrenees and reaches Toulouse; Marseilles, Aix, Piedmont attacked from Fraxinet. |

| 929 |

Fraxinet forces advance to borders of Liguria. |

| 931 |

Hugh of Arles invites Byzantine fleet to help him against the

colonists, but then makes peace with them; Andalusis occupy Alpine heights. |

| 940 |

Andalusis occupy and colonize Toulon. |

| 942-952 |

Andalusi settlement at Nice; Andalusi occupation of Grenoble; Andalusi fortresses in Piedmont: Fressineto and Fenestrelle. |

| 965 |

Andalusis evacuate Grenoble. |

| 970 |

Evacuation of Savoy by Andalusis. |

| 973 |

French town of Gap evacuated by Andalusis; Battle of Tourtour and

Andalusi evacuation of most

of Provence. |

| 975 |

Andalusi evacuation of Fraxinet. |

| 1003 |

Andalusis attack Antibes. |

| 1019 |

Andalusis attempt to recapture Narbonne; Maguelone attacked

by Andalusis. |

| 1047 |

Andalusi raid on Lérins Islands. |

|

Robert W. Lebling (lebling@yahoo.com), former assistant editor of Aramco World, is a staff writer and communication specialist for Saudi Aramco in Dhahran. He is author of the forthcoming Jinn: Legends of the Fire Spirits From Arabia to Zanzibar. |

|

Canadian freelance artist Norman MacDonald, a frequent contributor to Saudi Aramco World, used parchment paper and drew with twigs rather than brushes for a “medieval effect” in his illustrations. |