|

| GEMÄLDEGALERIE, STAATLICHE MUSEEN ZU BERLIN / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| Hans Holbein the Younger, “Portrait of Danzig Merchant Georg Gisze,” 1532. The vase with flowers and the Oriental carpet are the only items in the painting not connected to Gisze’s business. The flowers communicated romantic intent to his prospective fiancée; the carpet asserted status and gentlemanly refinement. |

It was an April afternoon in Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie—one of Europe’s premier art museums—and the prominent German businessman and I were eyeballing each other across a distance of about two meters and nearly five centuries. Well, actually, it was a portrait of him by the famous German Renaissance painter Hans

Holbein the Younger that I was eyeing.

Gisze was a member of the Hanseatic League, northern Europe’s powerful trading cartel, and the painting, for which he sat in London sometime in 1532, was to be sent to his prospective fiancée back home in Danzig.

Evidence of Gisze’s romantic intent is both subtle—the Venetian glass vase of pink carnations at his elbow that symbolized betrothal—and overt: The Latin inscription tacked to the wall attests that the painter has faithfully reproduced his subject’s “features and figure” as they appear “in real life.”

Holbein’s portrait also communicated the business end of Gisze’s marriage proposal—that he was a respectable, prosperous member of Europe’s emerging mercantile class—by depicting Gisze in his counting-house, surrounded by the practical tools of his trade: scales, pewter writing stand, leather-bound ledgers and contracts lining the wall. The one item in the painting that is not a business tool is the one that

covers his work table: a brightly colored Oriental carpet.

f all the status symbols in the painting, it was this carpet that intrigued me most, and it is what I had traveled to Berlin to see. Earlier that day, Jens Kröger, resident carpet expert at Berlin’s Museum of Islamic Art, had told me that the German merchant had had Holbein include the costly, imported carpet as a way to “show off his wealth and good taste.” Gisze might have been pleased to know that, in our own time, an entire class of Oriental carpets has come to be identified with the very one covering his desk—though he might perhaps have been disappointed that they were named not for him, but for the painter who rendered them in such vivid detail: Hans Holbein.

f all the status symbols in the painting, it was this carpet that intrigued me most, and it is what I had traveled to Berlin to see. Earlier that day, Jens Kröger, resident carpet expert at Berlin’s Museum of Islamic Art, had told me that the German merchant had had Holbein include the costly, imported carpet as a way to “show off his wealth and good taste.” Gisze might have been pleased to know that, in our own time, an entire class of Oriental carpets has come to be identified with the very one covering his desk—though he might perhaps have been disappointed that they were named not for him, but for the painter who rendered them in such vivid detail: Hans Holbein.

|

| NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| Below, right and detail, above: Hans Holbein the Younger, “The Ambassadors,” 1533. The painting is notable not only because its carpet is the one that gave rise to the term “large-pattern Holbein,”but also for its curious rendering, near its bottom center, of an anamorphic skull, discernible as such only when the painting is viewed at an acute angle. |

“[In Holbein’s] elegant paintings there are carpets and table-covers copied with wonderful minuteness of detail and the most elaborate care, so much so, indeed, that ... the very stitches of the pattern may be counted.”

So wrote Julius Lessing, one of a handful of German art historians who, during the late 19th century, began noticing and cataloguing the Oriental carpets that appeared in the paintings of such European masters as Holbein, Jan van Eyck, Lorenzo Lotto and Hans Memling. Lacking much information on the carpets themselves, these scholars came to rely on paintings from roughly the 14th through the 17th century—the heyday of the carpet trade between Europe and the Levant—for data on what was then the budding field of Oriental-carpet studies.

Linking the paintings of Hans Holbein to specific decorative weaving patterns, Italian Renaissance art expert and carpet collector Wilhelm von Bode, in his seminal 1902 study Antique Rugs from the Near East, coined the term “Holbein carpet” to label those carpets from western Anatolia that featured rows of knotted octagons (guls) and borders of interlacing, stylized Arabic script (“kufesque”). (See “A Beginner’s Guide to Carpet Patterns”) Later, additional carpet classifications followed, named for other painters—Lottos, Memlings, Bellinis, Ghirlandaios and Crivellis, together with subcategories such as “small-pattern Holbeins” and “large-pattern Holbeins.”

Beyond simply depicting the carpets (usually just enough of them to make clear the overall pattern), the paintings reveal important details of carpet manufacture, as well as intriguing facts about the significance of Oriental carpets in the spiritual, commercial and political lives of Europeans in the late medieval and early Renaissance eras.

|

|

Left: MUSEUM FÜR ISLAMISCHE KUNST / BILDARCHIV PREUSSISCHER KULTURBESITZ / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY;

RIGHT: PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART |

| Above, left: A “large-pattern Holbein” with four central squares and, above right, an Anatolian design whose strapwork border makes it akin to the

carpet in Holbein’s portrait of Georg Gisze. |

“Oriental carpets represented wealth, power and holiness,” said Walter Denny, professor of art history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a leading Oriental carpet expert. UMass Amherst is one of the only institutions (the other is Oxford University) to offer an advanced degree in carpet history. Remarkably, art and textile historians like Denny, as well as museum curators, private collectors and carpet dealers, continue to rely on paintings to inform their understanding of carpets from North Africa, the Levant and Turkey, particularly when it comes to dating them and determining their origin.

“No question,” Denny assured me. “Paintings are still the bedrock on which the story of Oriental carpets is based.”

What was that story? What advantages do 500-year-old paintings have over chemical analysis, electron microscopy, molecular forensics or any other modern tools available to textile historians these days? And is it possible to somehow trace a carpet, or a carpet style, from oil on canvas back to its source—wool on a loom?

racking down answers to these questions required an itinerary that might have been lifted from a Cold War spy novel: Berlin to Istanbul, then across the Bosporus to remote mountain villages of western Anatolia that the medieval world travelers Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo may have passed through, and would likely still recognize.

racking down answers to these questions required an itinerary that might have been lifted from a Cold War spy novel: Berlin to Istanbul, then across the Bosporus to remote mountain villages of western Anatolia that the medieval world travelers Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo may have passed through, and would likely still recognize.

My first, admittedly less exotic, stop was the Amherst home of professor Denny and what you might call his Oriental-carpet command center—his home office and library. Surrounded by thousands of catalogued volumes and images related to carpets, we talked about the field of carpet studies, the peak centuries of the carpet trade (14th through 16th), the freely acknowledged obscurity of the field and, in it, the enduring importance of paintings.

|

| GALLERIA DELL’ ACCADEMIA, VENICE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

| Below, right and detail, above: Paris Bordone, “Fisherman Returning the Doge’s Ring,” 1534. It was around this time that painters began to show carpets beneath the feet (and thrones) of royalty. |

“We have inventories of carpets from the Medicis and others, but the inventories never tell you what the carpets actually looked like. The paintings do,” said Denny.

He had a point. Venetian and Florentine inventories from the 16th century that mention Oriental carpets (tapedi or tappeti) often do so only vaguely. The most ornately patterned rug might be identified only by its dominant color, for example, uno tappeto rosso (“a red carpet”) or uno tappeto verde (“a green carpet”). Geographical qualifiers are no more helpful: tapedi cagiarini (a Cairene carpet, from Egypt), tapedi damaschini (a carpet sold—but not necessarily made—in Damascus), tapedei turcheschi (Ottoman), barbareschi (North African) and rhodioti (imported via—or possibly made in—Rhodes). Worse, these toponyms often were used both interchangeably or as catchalls to describe any Oriental carpet. Even tapedi could mean either carpets or tapestries.

|

| TEXTILE MUSEUM |

| This star-Ushak carpet, above, from west-central Anatolia, dated to the late 16th century. |

Then there is a raft of classifications that, to the layman’s ear, sound oxymoronic: tapedo da tavola (“table carpet”), tapedo serve il descho (“carpet that goes on a desk”), tapedo sul descho da scrivere (“carpet on the writing desk,” as in Holbein’s portrait of Gisze), tapetti da letto (“bed carpets”) and tapetti da banco (“bench carpets”). There were even subcategories of covers for carpets—a practicality when food, wine or other staining substances were being handed around the family’s tapedo da tavola. (Accidents can happen. I certainly wouldn’t have wanted to be the one to inform the notoriously short-tempered, axe-happy Henry VIII that one of his desk carpets, as noted in the royal household inventories, was “steyned with yncke.”) In fact, the paintings and the records show that Oriental carpets were objects far too precious to leave lying around on the floor.

|

| NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON |

| Artist unknown, “The Somerset House Conference,” 1604, which depicted treaty negotiations between Spanish and English delegates. They met at a table covered by an extraordinarily large carpet. |

“Oriental carpets were extremely costly and associated with high social status,” said Denny. “Walking on expensive, imported textiles was something only royalty did.”

And saints. From the mid-13th to the mid-15th century, artists often painted carpets beneath the feet of Christian religious figures, most frequently Mary, Jesus and various saints. This iconographic use of carpets may have been inspired by carpet uses in the lands of their origins. The Qur’an (88:15-16) describes heaven as a garden, with “cushions set in rows, and rich carpets (all) spread out,” while chapter 55, verse 76, lists “rich carpets of beauty” among the pleasures of paradise. The well-known use of carpets in mosques, in fact, inspired yet another Italian classification, referring to prayer rugs: tapedi a moschetti (“mosque carpets”).

By the mid-16th century, Oriental carpets also began appearing in paintings beneath the feet of European kings and high officials. Court portraits of both Henry VIII and his heir, Edward VI, show them striking similar poses on, respectively, an eight-lobed medallion Ushak carpet and a small-pattern Holbein. Paris Bordone’s 1534 “Fisherman Returning the Doge’s Ring” shows the Venetian ruling council on a raised dais draped with a large “star-Ushak” carpet. More famously, Holbein’s 1533 “The Ambassadors” shows the carpet after which “large-pattern Holbeins” were named.

|

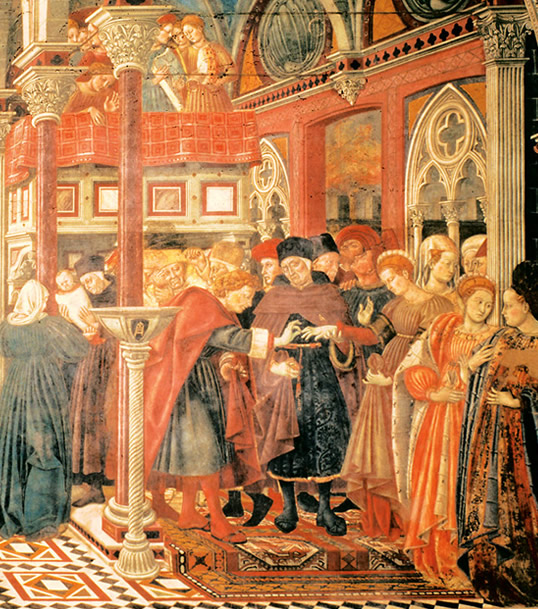

| OPESDALE DI SANTA MARIA DELLA SCALA / F. LENSINI / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY; |

| Below, right and detail, above: Domenico di Bartolo, “Marriage of the Foundlings,” ca. 1440. Note that carpets appear not only beneath the wedding party’s feet, but also draped from the balcony above. |

Publicly, carpets were displayed draped off bridges, buildings and (in Venice) even gondolas on festival and feast days. Venetian Senate secretary Marino Sanuto in his diary described a procession in the Piazza San Marco: “[E]l palazo era tutto conzato la faza sopra la piaza verso el campaniel di tapezarie ... cosa belissima a veder.” (“The façade of the Doge’s palace facing the bell tower of St. Mark was covered in carpets ... a most beautiful thing to behold.”) A dozen years earlier, Italian artist Gentile Bellini—for whom “Bellini carpets”

are named—had painted just such a scene.

|

| THE YORCK PROJECT / WIKIMEDIA COMMONS |

| Above: Frans Floris, “Portrait of the Van Berchem Family,” 1561, which shows use of a plain cover cloth to protect the table-carpet. |

Here again, the Muslim world may have provided precedent. The 15th- and early 16th-century Egyptian historian Ibn Iyas reported that the throne of Mamluk sultan Qansuh al-Ghawri stood upon a large carpet, and on state occasions part of his route through Cairo was strewn with carpets made of silk. Likewise, in the late 15th century, the Venetian traveler Giosafat Barbaro, on a mission to the court of Turkmen sultan Uzun Hasan, witnessed a public festival in Tabriz where freshly mown grass beneath royal pavilions was “covered [with] the most beautiful carpets ... of Cairo and Bursa.”

As so often happens in the world of material culture, what is in vogue among the rich one day soon becomes the must-have of the middle class. So, from the latter part of the 16th century, possession and display of Oriental carpets became a way for upwardly mobile bankers, merchants and the like—Georg Gisze among them—to advertise their arrival at positions of social status. Thus, in a 1543 fresco by Moretto da Brescia, the rich and lovely daughters of the house of Martinengo strike rich and lovely poses on the family’s prized Mamluk rugs, and in Lorenzo Lotto’s 1524 “Portrait of a Married Couple,” the subjects appear proud of their handsome, prominently displayed Bellini table carpet. Likewise, Lotto’s patron and landlord, Niccolo Bonghi, makes a cameo appearance in the artist’s 1523 “Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine”: He appears standing beside a pair of what are presumably his Anatolian prayer rugs. (Here, Lotto killed two birds with one brush: Not only did he exchange the painting for a year’s rent, he highlighted his patron’s connoisseurship by turning back the edge of the carpet beside Bonghi’s head to display the quality of its knotting.)

Another notable detail is the placement of a carpet on a window ledge during special occasions or, ostensibly, for airing out—the 16th-century equivalent of washing your Lexus in front of the neighbors. For those who could only afford to be king for a day, carpets were available for rent; for the truly budget-minded, there were (just like today) many imitations or knockoffs: Carpets from the Balkans, then part of the Ottoman Empire, and Spain, with its lingering Muslim culture and its craft traditions, were of reasonable quality, while those made in Italy, Flanders and England were notably less so. Throughout the period, by far the most coveted were those “of Turquey makinge” (as noted in Henry VIII’s inventory), specifically those woven in the western Anatolian region.

|

| ACCADEMIA CARRARA / ERICH LESSING / ART RESOURCE |

| Below, right and detail, above: Lorenzo Lotto, “Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine,” 1523, in which the artist turned back the edge of one of the patron’s carpets to show the high quality of

its knotting. |

Italy—the ports of Venice and Genoa in particular—was the conduit through which most of these rugs arrived in Europe, under trade arrangements that dated back to the high Middle Ages. Even the conquest of Christian Byzantine Constantinople by Mehmet II’s army in 1453, and its renaming as Istanbul, didn’t much interrupt the flow of carpets. Genoese merchants, under a new trade agreement with Mehmet, moved offshore to the Greek island of Chios while continuing to supply the Turkish carpet-weavers with a key ingredient for making their dyes colorfast: alum, mined in both central Italy and Italian-controlled centers within Turkey.

Yet the prominence of Oriental carpets in western paintings indicates more than a thriving, symbiotic mercantile relationship. The West’s high regard for rugs “of Turquey makinge” literally illustrated a cultural affinity.

“Carpets were the one Islamic art form known as well in the West as in the East,” Denny observed. “They were part of the material cultures of both worlds at the same time.”

hile Venice was a major intersection for these two cultures during the Renaissance, it was Germany, not Italy, that was next on my journey—specifically, Berlin, the birthplace of Oriental-carpet studies, with its famed Museum of Islamic Art. That prestigious institution remains home to one of the world’s largest and finest collections of the so-called painter carpets, and the capital’s leading picture gallery, the Gemäldegalerie, which features paintings in which the carpets appeared. Though housed separately, they afforded me an opportunity to view both paintings and textiles, if not side by side, at least in the same day.

hile Venice was a major intersection for these two cultures during the Renaissance, it was Germany, not Italy, that was next on my journey—specifically, Berlin, the birthplace of Oriental-carpet studies, with its famed Museum of Islamic Art. That prestigious institution remains home to one of the world’s largest and finest collections of the so-called painter carpets, and the capital’s leading picture gallery, the Gemäldegalerie, which features paintings in which the carpets appeared. Though housed separately, they afforded me an opportunity to view both paintings and textiles, if not side by side, at least in the same day.

The textile conservation room of Berlin’s Museum of Islamic Art, like so much in this once famously divided city, is a legacy of the Cold War. When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 and the museum’s treasured collection—including separated halves of single carpets—was reunited under one roof in the Pergamon Museum, the conservation room remained behind in the former West Berlin because of the Pergamon’s lack of space.

|

| SS GIOVANNI E PAULO / CAMERAPHOTO ARTE / ART RESOURCE |

| Lorenzo Lotto, “Alms of St. Anthony,” 1542 (detail). |

|

| ARCHIVO FOTOGRAFICO BRESCIANO / FOTOSTUDIO RAPUZZI |

| Moretto da Brescia (Alessandro Bonvicino), “Daughters of the House of Martinengo, Brescia,” 1543 (detail, fresco). |

|

| ACCADEMIA, VENICE / CAMERAPHOTO ARTE / ART RESOURCE |

| Giovanni Mansueti, after 1494, (detail): Men and women drape carpets from their windows during a procession. |

Conservator Annette Beselin doesn’t mind the remoteness of her workspace in Dahlem, a few kilometers outside central Berlin. It allows her the peace and quiet to concentrate on her job of restoring antique carpets and textiles in a setting that looks like a cross between a crime lab and a sewing boutique. Microscopes and beakers of special cleansing chemicals compete for space with spools of thread, bolts of cloth and shelves of art books featuring images of the paintings Beselin relies on when deciphering the details of antique carpets.

“The paintings are important because they not only help us classify the different types of carpets, but also provide precise details about the carpets themselves,” said Beselin. These details include a carpet’s likely place of origin, based on its pattern, and, most importantly for someone in

Beselin’s line of work, its age—or, at least,

a terminus ante quem.

“The ante quem date is the latest date something can have been created,” Beselin explained. “For example, if I see a carpet in a painting and I know the painting is dated 1540, then I know that the carpet was made earlier than 1540.” Even how much earlier it was made can be answered by a close examination of the paintings, Beselin told me.

“Painters like Holbein were very accurate,” she said. “If you look closely at the

carpets in the paintings, you can see details like worn edges or worn spots. This helps determine the age of the carpet in the painting, which tells you when that type of carpet was being made. I can then compare the

carpet in the painting to other carpets and determine their age. It’s like working out

a puzzle.”

But what of carbon-14, I wondered. Wouldn’t that standard scientific method for dating organic material (such as wool) solve the puzzle more efficiently?

“The carbon-14 method only gives you a date accurate within about 200 years. You can’t get an exact date,” Beselin told me. Beyond that, the paintings provide data no laboratory ever could: information on objects that don’t exist.

“The paintings can give you examples of carpets that haven’t survived or been found yet,” said Beselin. “They can help to fill in gaps between different types of carpets that we know from museum collections, so they help to show design or motif developments at the time.”

“The paintings can give you examples of carpets that haven’t survived or been found yet,” said Beselin. “They can help to fill in gaps between different types of carpets that we know from museum collections, so they help to show design or motif developments at the time.”

Employing a sort of reverse logic, scholars have even looked to carpets in paintings to learn about the artists themselves. Bode observed that the colors of Oriental carpets may have influenced the palettes of artists like Holbein, while, more recently, carpet expert Luca Emilio Brancati suggested that carpets depicted in unsigned paintings could help identify the mystery artists.

“Judging from the paintings, it would seem that every artist tends to paint a carpet always using the same method,” Brancati wrote in a 1999 Italian exhibition catalogue. “[T]his could prove to be a useful attribution tool.”

But be warned: Looking too closely at carpets in paintings has a psychological side effect, Beselin suggested—what you might call “carpetomyopia.”

“When I look at this painting, all I see is the carpet,” she said, flipping to a picture of Andrea Previtali’s “Annunciation,” which features, among quite a few other things,

a beautiful, intricate, small-pattern

Holbein carpet.

“You begin to notice carpets everywhere in paintings. It will happen to you too,” she cautioned me with a smile.

“You begin to notice carpets everywhere in paintings. It will happen to you too,” she cautioned me with a smile.

She was right.

As I wandered through the Gemäldegalerie later that day, it seemed there were carpets in every painting. Some I had come to see specifically, like the one in Holbein’s portrait of Gisze or the Cairene-patterned carpet in Georg Pencz’s 1534 “Portrait of a Young Man.” But throughout the gallery

I noted dozens of others, draped across tables in Rembrandts, de Keysers and Valckerts, or at the feet of religious figures in Memlings.

|

|

| LEFT: BELVOIR CASTLE / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY; RIGHT: NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON |

| Left: Hans Holbein the Younger, “Henry VIII,” early 16th century, showns him standing on a carpet. Right: Hans Eworth (attributed), King Edward VI, 1547. |

As Beselin said, the artists did a remarkable job of capturing the subtle details of knotting, patterns and colors, and soon I wanted a look at the textiles that had inspired the paintings. That meant a visit to the Pergamon Museum. Though it’s famed for its towering reconstructions of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate and its namesake altar from ancient Pergamon (modern Bergama, Turkey), students of Islamic cultures know the Pergamon Museum of Islamic Art as the repository of some 500 Oriental carpets and carpet fragments, ranging in date from the 15th to the 19th centuries, woven in places from Andalusia to India. Much of the collection was donated by Bode, who rummaged through Italy’s castles and churches in search of carpets during the early 20th century when they were, incredibly, being tossed away as rags. “In Italy, at that time, they practically lay in the streets and could be had for a song,” he wrote in his memoirs.

Thanks to Bode’s keen eye, these “rags” now rest in climate-controlled cases and hang in hushed, windowless rooms under controlled lighting on the Pergamon’s second floor, where Kröger walked me through the exhibition. If anyone in town could be considered Bode’s successor, it is this self-effacing, avuncular scholar, though he’d likely decline the honor. Like many in his field, he pleads ignorance when it comes to reliable data on the history of Oriental carpets, and he attributes much of what is known to paintings.

“The weavers left no production records,” he said. “All that we know we must learn from paintings and from the carpets themselves.”

Strolling through the galleries, Kröger pointed to examples of large- and small-pattern Holbeins, Lottos, and others—carpets that Bode, with his vast knowledge of Renaissance art, matter-of-factly associated with various painters. With Kröger’s help, even I began to recognize patterns and nearly identical carpets from Holbein’s “The Ambassadors,” Previtali’s “Annunciation,” Antonello da Messina’s “St. Sebastian” and—almost knot-for-knot—Lotto’s “Mystic Marriage.”

|

| NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON / ART RESOURCE |

| Above: Niccolo di Buonaccorso, ca. 1380: The Marriage of the Virgin (detail), shows a design similar to, but simpler than this carpet fragment from Turkey, below, left, dated about 1400, which depicts a battle between a dragon and a phoenix. |

|

| BILDARCHIV PREUSSISCHER KULTURBESITZ / ART RESOURCE; |

Meanwhile, this man of unduly modest claims managed to fill a good part of my notebook with carpet terms such as guls (octagonal patterns characteristic of Holbein carpets), “kufesque,” “knucklebone” and “arms akimbo” border designs; Spanish vs. symmetrical vs. asymmetrical knotting, and how all these details, together with the paintings, can pinpoint a carpet’s regional origin. Other design clues, such as coats-of-arms or monograms, point to custom manufacture for aristocratic European clients, he said, while textual evidence mentions mass-production centers whose output was exclusively for export to the West.

“There were made-to-order, and there were carpets sold by measurement. The workshops were kept very busy,” said Kröger.

Perhaps the busiest were in western Anatolia, a region stretching from the Marmara Sea to the Mediterranean and from the lofty, lonely Taurus Mountains to the tattered Aegean coast. While the Ottoman-era court and commercial workshops are long gone, this region still produces some of the world’s finest handmade carpets, woven with naturally dyed, homespun wool on looms that haven’t changed much since the first Holbein carpets were created there six centuries ago. Would Anatolian village weavers recognize their ancestors’ handiwork in the paintings, I wondered. Could I hold in my hand not some replica but a contemporary carpet that had centuries of tradition woven in its warp and weft, a product as captivating to modern eyes as it was to the Medici or to Renaissance artists? The answers to these and other such questions lay to the east, through the port of Istanbul, commercial gateway between Europe and Asia since the days of Homer.

ompared to the fabled, frenetic Covered Bazaar, Istanbul’s artsy, low-key Arasta Bazaar, in the shadow of the Blue Mosque, seems like a retirement home. Moustachioed rug merchants sit outside their shops sipping tea from tulip-shaped glasses and playing backgammon in between customers. Less cajoling than their brethren in the Covered Bazaar, these fellows employ a craftier gambit: an ingratiating cup of tea and a gentle, no-pressure invitation to examine the merchandise.

ompared to the fabled, frenetic Covered Bazaar, Istanbul’s artsy, low-key Arasta Bazaar, in the shadow of the Blue Mosque, seems like a retirement home. Moustachioed rug merchants sit outside their shops sipping tea from tulip-shaped glasses and playing backgammon in between customers. Less cajoling than their brethren in the Covered Bazaar, these fellows employ a craftier gambit: an ingratiating cup of tea and a gentle, no-pressure invitation to examine the merchandise.

One of the city’s top dealers keeps shop just west of the Arasta, in a store that looks more like a hip boutique than an Oriental rug business. Funky felt hats are a hallmark of Şeref Özen’s Cocoon Galleries, but when it comes to carpets, his whimsy gives way to worldliness.

“I deal in very old, tribal material from Central Asia—Persian, Uzbek and Turkish weavings primarily—for clients who are collectors,” he said, handing me an unduplicitous glass of tea across his desk. Urbane and sophisticated, with a better command of English than mine, Özen, with shoulder-length gray hair, denim shirt and basketball sneakers, looked more like a Los Angeles studio musician than one of Istanbul’s most exclusive carpet dealers. Yet his reputation has less to do with his haberdasher than with his knowledge of carpet history.

“During the Renaissance, more carpets were made for export to Europe than for the local Turkish trade,” he told me, echoing Kröger’s observations. In contrast to their humble origins as domestic, tribal weavings, Özen said, the oversized Oriental carpets in European paintings were evidence of a consumer base that simply could not get enough.

“The European market was an Orientalist market, and Orientalists tend to overdo it,” he remarked. “We don’t put carpets on tables in the East; we put them on the ground to sit on.”

And to pray on: Just as Bode exhumed treasured-but-forgotten Oriental carpets from European churches, scholars have since discovered hoards of prize carpets in medieval mosques throughout central and eastern Anatolia. I spent an afternoon inspecting many such finds in Istanbul’s Museum of Turkish and

Islamic Arts.

Arranged chronologically, the exhibits tell the story of Turkish carpet weaving—including sections devoted to the painter carpets—from its origins in the Bronze Age (3300–1200 BC) to the late 19th century.

To wander from room to room is to follow, in effect, a dotted line across a map of Central Asia, where the local tradition of knotted, pile-carpet weaving was probably introduced by pastoral nomads who themselves adopted the craft from prehistoric villagers.

|

| Tom Verde |

| Weavers in Örselli, Turkey prepare pots of natural dye for wool skeins hung on the stone wall. Thanks to the DOBAG Project, carpet-weaving traditions here continue to resemble those that produced the carpets

so much admired in Renaissance Europe. |

Modern villagers still weave

carpets the same way in the western Anatolian highlands, where Ibn Battuta noted a thriving export trade in “sheep’s wool carpets” and which Marco Polo credited as the source of the “finest and handsomest carpets in the world.”

few days later, following the dusty wake of these legendary travelers, I was bouncing along a dirt track to the village of Sülemanköy, near the market town of Ayvacık in western Turkey’s Aegean Peninsula. At the wheel to my left was Şerife Atlıhan, professor of traditional textile art at Istanbul’s Marmara University. A native of Fethiye, on the southern Aegean coast, Atlıhan—like countless generations of Turkish girls before her—learned at her mother’s knee how to spin wool and weave. Unlike those countless generations, however, Atlıhan spun her domestic chore into an academic career, and she works now as an advisor to self-supporting cooperatives that make traditional carpets using homespun wool and natural vegetable dyes. (See “Back to Nature,” page 6.) Her job is to liaison with the weavers—settled Yörük tribal nomads with whom she has close, long-standing relationships—and make sure the quality of the carpets remains consistent.

few days later, following the dusty wake of these legendary travelers, I was bouncing along a dirt track to the village of Sülemanköy, near the market town of Ayvacık in western Turkey’s Aegean Peninsula. At the wheel to my left was Şerife Atlıhan, professor of traditional textile art at Istanbul’s Marmara University. A native of Fethiye, on the southern Aegean coast, Atlıhan—like countless generations of Turkish girls before her—learned at her mother’s knee how to spin wool and weave. Unlike those countless generations, however, Atlıhan spun her domestic chore into an academic career, and she works now as an advisor to self-supporting cooperatives that make traditional carpets using homespun wool and natural vegetable dyes. (See “Back to Nature,” page 6.) Her job is to liaison with the weavers—settled Yörük tribal nomads with whom she has close, long-standing relationships—and make sure the quality of the carpets remains consistent.

“The weavers can choose whatever colors and patterns they want, as long as they are traditional Bergama types—Holbeins, Memlings, Ghirlandaios and so forth,” said Atlıhan, whose first task upon arrival at the co-op is to inspect size, pattern spacing and knot counts—90,000 to 110,000 knots per square meter (8400–10,200 per sq ft), no more, no less.

This is not only to ensure authenticity, but also because modern customers—like their Renaissance-era predecessors—desire specific sizes, patterns and colors, said Atlıhan. Americans, for instance, like big carpets (no surprise), Scandinavians prefer moderation (again predictable), while Dubliners have an aversion to green (which I did not see coming).

The carpet patterns do not exist on paper, but only in the minds and collective memories of the weavers, who greeted Atlıhan in the shade of what amounts to Sülemanköy’s town square—a flagstone terrace beside a public water trough, in the shadow of the mosque. Many of these women have never ventured far beyond Ayvacık, let alone wandered the galleries of a Renaissance art exhibition. Yet when I pulled out a book featuring images of Oriental carpets and the paintings in which they appeared, they hovered over the volume like ladies at a class reunion recognizing old friends in a yearbook.

The carpet patterns do not exist on paper, but only in the minds and collective memories of the weavers, who greeted Atlıhan in the shade of what amounts to Sülemanköy’s town square—a flagstone terrace beside a public water trough, in the shadow of the mosque. Many of these women have never ventured far beyond Ayvacık, let alone wandered the galleries of a Renaissance art exhibition. Yet when I pulled out a book featuring images of Oriental carpets and the paintings in which they appeared, they hovered over the volume like ladies at a class reunion recognizing old friends in a yearbook.

“Ah, Holbein, Holbein, Lotto,” they chattered, pointing to carpets in various paintings, the patterns of which are as familiar to them as their own children, even though they had never heard of Hans Holbein, Lorenzo Lotto or any of the other artists whose works are inextricably linked to 500 years of Oriental carpet history. Casting a professional eye on a 16th-century Ushak medallion carpet pictured in my book, weaver Şerife Ergün shook her kerchief-covered head.

“Ugh, too difficult,” she said. “This one would take a long time to make.”

This is not to say that the carpets these talented women weave are casual approximations of the real things of a bygone era. They are indeed about as close to them as you are likely to find this side of an original Holbein, as I was delighted to discover the next day in the mountaintop village of Örselli, near Manisa.

|

| Tom Verde |

| A selection of designs from the modern weavers of Örselli is laid out for display in a park. |

A scattered collection of red-tile roofs on stone houses sloping into the hillside, Örselli is home to a co-op similar to the one in Sülemanköy. The remains of a Roman road run along the outskirts of the village, adding heft to Atlıhan’s declaration that this region has been a center of textile trade and manufacture for centuries.

As co-op members organized their carpets for Atlıhan’s inspection, my eye caught one that truly looked as if it could have been peeled from the surface of a painting. It had all the elements of a classic, small-pattern Holbein: the rich blend of blues and reds and a “kufesque” border encasing a pattern of knotted octagons. My guess wasn’t far off: Consulting some art-history literature, I found a near match in an anonymous 15th-century Italian painting, attributed to the Lucchese school.

Later, I watched these women spin the wool gathered from their flocks, dye it in steaming pots and transform the balls of colored yarn into works of art on upright looms, each purposefully positioned by exterior doorways so as to catch as much daylight as possible. I wanted to ask them if they felt a connection with the past I’d just traced across three continents. Then it occurred to me that they were themselves the living answer to my question. Like the carpet resembling the one from the Lucchese painting, these women and their craft are both the present and the past—or as close to it as any of us is likely to get.

Georg Gisze was right. I was impressed. Very impressed, indeed.

|

Writer Tom Verde (writah@gmail.com) holds a master’s degree in Islamic studies and Christian–Muslim relations from Hartford [Connecticut] Seminary, and is currently on the faculty of the Department of Ethics, Philosophy and Religion at King’s Academy in Amman, Jordan. |