|

|

|

| LEFT: BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE / ART RESOURCE; RIGHT: MUSEO CORRER, VENICE / GIRAUDON / BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

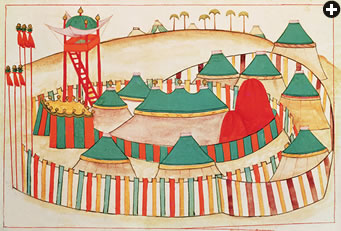

| Left: Initially used as simple shelters by nomadic peoples on the Central Asian steppe, tents had evolved into luxurious portable abodes by the time of Genghis Khan, the Mongol conqueror who ruled a vast region at his death in 1227. This illustration comes from a 14th-century Persian manuscript. Right: A splendid entryway marked by horsetail banners leads into a tent city designated “the imperial camp” in a 15th-century gouache sketch of the Islamic School. |

|

rom the Middle Ages onward, European travelers, such as the Spanish envoy quoted at left, wrote admiringly of great tent cities in Muslim lands—especially in Central Asia, but also in Turkey, Egypt and later Mughal India. They were astonished at the size and organization of these cities that at times numbered thousands and even tens of thousands of tents.

rom the Middle Ages onward, European travelers, such as the Spanish envoy quoted at left, wrote admiringly of great tent cities in Muslim lands—especially in Central Asia, but also in Turkey, Egypt and later Mughal India. They were astonished at the size and organization of these cities that at times numbered thousands and even tens of thousands of tents.

The cities that amazed Europeans were not simply the black camel-hair ridge tents of the Arab world or the domed yurts of the nomadic Central Asian tribes. They included movable palaces, some complete with mosques, that housed traveling royalty and their vast entourages, or were set up to mark important celebrations, such as the marriage or circumcision of members of the ruling house. And it was not just the size of these tents that caught western eyes, but their splendor and comfort, and the way they served as showcases for wonderful textiles: cloth of gold, brocade, ikat, embroideries, velvet, chintz and appliqué.

|

| INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES, ST. PETERSBURG / GIRAUDON / ART RESOURCE |

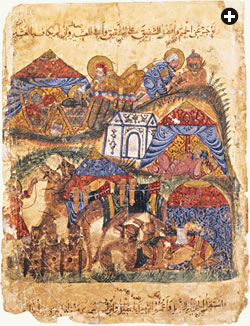

| This illustration by Yahya al-Wasiti from a 13th-century edition of the Maqamat (Assemblies), a collection of Arabic poetry by al-Hariri of Basra (1054–1122), depicts a caravan stop with brightly colored tents in which travelers could rest and where they could care for their mounts. |

Across the world, nomads have used different types of shelters and tents, but some of the most varied and elaborate designs originated on the Central Asian steppe, a region that can be hot in summer, bitterly cold in winter and windy at any time. For centuries, but mainly from early medieval times onward, as diverse Turco-Mongol peoples spread out from the steppe in migrations or in conquest, they carried with them their circular dwellings, called yurt in Turkic or ger in Mongol. Even after they settled and began to build houses and palaces, they often returned to their tents for the major events of their lives: birth and death, feasting and all kinds of ritual occasions.

This ceremonial use of the tent reached as far east as China, where there was considerable influence from the steppe, especially along the western border. Paintings show that an 11th-century Song empress gave birth in a special delivery tent, surrounded by 48 smaller ones. Among people who were originally nomadic, the custom of giving birth in a tent survived, particularly in Siberia, into the 20th century, possibly in part because of an awareness that a place never before occupied reduced the risk of infections.

Early accounts of yurts or gers—circular, with a collapsible willow frame covered in felt and a domed roof, sometimes also called "trellis tents"—come from Chinese descriptions and paintings that date to the ninth century. However, it is around the late 12th and early 13th centuries, during the time of Genghis Khan, whose rule extended from northern China to the Volga River in Russia and south to Persia, that travelers and envoys began to describe the luxury of the ruler's tent. Chinese author Hei-Ta Shih Luëh, writing about 1237, tells us that "[i]t is secured with more than a thousand ropes. It has one door. The threshold and doorposts are completely faced with gold. For this reason it is named 'golden.'"

A couple of years later, the Persian historian Ata Malik Juvaini described the opulent tent his father, the sahib-divan, or finance minister, of Khurasan, provided for the Mongol court: "My father provided another great tent of marvellous artifice and wondrous coloring with everything in keeping in the way of gold and silver vessels. He pitched this tent and feasted in it for days on end."

|

| METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART / ART RESOURCE |

| A classic yurt—a tent with a wooden lattice frame and felt walls, its roof and walls held in place by braided ropes and woven straps—is the venue of a concert on the steppe depicted in Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute: The Story of Lady Wen-Chi, a 14th-century tale of a Chinese woman kidnapped by Huns and held in their camps for years. |

Already by this date, a number of different types of tents were in use among the Turco-Mongol peoples, apparently as a matter of personal taste and wealth. Miniatures illustrating the famous Maqamat (Assemblies) of al-Hariri—for example, in a manuscript written in Baghdad around 1240, now in St. Petersburg—show trellis tents, bell tents—circular with a central pole—and ridge tents all pitched side by side at caravan halts outside Damascus and elsewhere, and at the pilgrims' camp at Makkah.

These tents are elaborately decorated, perhaps reflecting the imagination of the artist, but more likely recording what they actually looked like. Some have designs similar to those still found today on suzanis, the richly embroidered textiles from Central Asia; another is decorated with a band of calligraphy reflecting the architecture of the period, and yet another appears to be appliquéd. These decorative traditions were carried from east to west across the steppe. Until recently, they were still found on tents in Tibet, and they are still used on the ceremonial tents of North Africa and Egypt.

These beautiful structures did not stand in isolation: They were often part of cities of more than 20,000 tents, with the ruler and his wives housed in what were indeed tent palaces. Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo, the Spanish ambassador to the court of the Mongol emperor Timur in Samarkand in 1404, described the royal tents in such detail that it would be easy to reconstruct one. (See sidebar, below) By his time, the simple yurt-type tent had been extended into the ceremonial marquee, with its entryway enclosure held up by poles. These marquees could be vast: The 14th-century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta mentions one large enough to contain a minbar, or pulpit, and accommodate several hundred men at prayer.

The people of the steppe who had come into contact—and initially conflict—with settled Muslims (including most infamously the 1257 sack of Baghdad that brought down the Abbasid caliphate) converted to Islam. From roughly the 14th century, their conquests took the traditional tent in two directions: to Turkey and to India.

In Turkey, tents became a vital part of the Ottoman Empire. They held a special place on ceremonial occasions, in part due to the Ottomans' own nomadic past, and they were also a critical item of equipment in a highly militarized society. The Ottoman army even had a department to deal with them, and the sultan's own tents were stored in Istanbul at a depot near the Ibrahim Pasha Palace on the great hippodrome. Around the time of the Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453, 38 men were employed in pitching the royal tents, and by the end of the 17th century, that number had risen to 2000.

|

| SAMMLUNG ANGEWANDTE KUNST, KASSEL / BRUNZEL / BRIDGEMAN. |

| Repeating rosettes, arches and images of hanging lamps decorate the interior of this 17th-century Ottoman tent. Real lamps would have been hung from the ridgepole. The tent was doubtless meant for an aristocrat or high-ranking administrator. |

Examples of Ottoman tents have been preserved in the Topkapı Palace and Istanbul Military Museums, but some of the finest are in treasuries and museums around Europe, where they were acquired either as battle trophies or as gifts proffered by one sovereign to another. (It is not difficult to tell which are which: Campaign tents tend to show much wear, while gift tents are relatively pristine.)

|

| TOPKAPI PALACE MUSEUM / RMN / ART RESOURCE;UPPER: BRITISH MUSEUM / ART RESOURCE |

| This brilliant silk panel highlights an 18th-century Ottoman summer tent now in the Topkapı Palace Museum in Istanbul. |

|

| ERICH LESSING / ART RESOURCE |

| This ornate Ottoman tent, from the late 17th century, is among the hundred thousand said to have been left behind by the departing Turks when they lifted the siege of Vienna in 1683. It is displayed at Wawel Royal Castle in Krakow, Poland. |

In 1683, the Polish king Jan iii Sobieski routed the Turkish army that was besieging Vienna. Among the spoils listed by a London newssheet were "sixty thousand tents and two millions of money in the Grand Vizier's tent." While the precise number of tents is probably a journalistic exaggeration, the Ottoman camp was indeed abandoned, and Sobieski, writing to his wife a few days after his victory, mentions the great quantities of tents acquired. Many of the tents in European collections today were among those captured at the Siege of Vienna.

A good deal is known about these tents. Some were made in government workshops. Others appear to have been commissioned in Aleppo and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. Evliya Çelebi, in his wonderful description of the Guild Processions at Istanbul in the late 17th century, says a little about the tent-makers: "Their patron was Nassir ben Abdullah Mekki, the tent maker… [who had] made the Prophet's tent…. They erect fine tents on litters … [while] some are busy setting up awnings and mosquito nets." He also mentions that the tent-rope makers prepared beautifully colored cords, and there existed also a mosquito net-makers' guild.

As in other matters at court, there was a strict hierarchy of tents, with the most splendid decoration, and the color red, reserved for the sultan and the highest military ranks. Bearing in mind the harsh climate of much of the Ottoman territory, camping tents (as opposed to ceremonial tents) were generally made in two layers, the outer composed of heavy, weatherproof material, often with very little decoration, while the inner , which is generally what has survived, could be extremely elaborate.

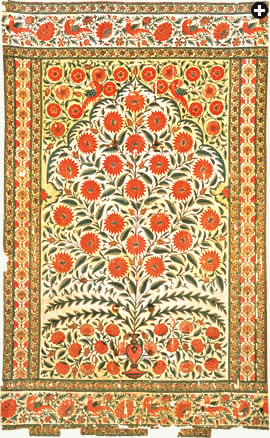

One of the most common decorative techniques was appliqué. Cut-out layers of material, which might include gilded leather, were stitched together in designs that generally imitated architectural motifs: arches, columns, oil lamps, sun rosettes, flower vases or the tree of life—all motifs in the classic Islamic repertoire.

The Ottoman tents now in the Royal Armory in Madrid are excellent examples of this. One, probably dating to the mid-17th century, shows signs of a number of years' use and careful repairs before it was captured, possibly at Vienna. Highly prized, it appears to have been passed around the European nobility as a ceremonial gift until it was given in 1881 by the Prince of Pescara in Italy to Alfonso xii . The tent is believed to have belonged to a high, but not top-ranking, official, and it would have weighed some 500 to 600 kilograms (around 1100 to 1300 lbs), which would have required three camels to carry.

Other fine tents, several from the same period, have been preserved—not surprisingly—in Hungary and Austria, countries bordering on the former Ottoman Empire, and as far away as Sweden. The largest collection is at Wawel Royal Castle in Krakow, Poland. One particularly lovely example, dating from the early 17th century, but also believed to have come from the siege of 1683, is oval, two-masted and wonderfully decorated in predominantly blue and gold. Another is mainly red with bold arcade and medallion decoration in stronger colors: green, yellow and blue.

Giving tents as gifts was nothing new: As far back as 802, Harun al-Rashid, the fifth Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, is recorded sending one to Charlemagne of France, along with the more famous elephant.

One of the most spectacular surviving gift tents, preserved in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, was presented in 1893 to Tsar Alexander iii by the Emir of Bukhara. The tent and its surrounding curtain walls are literally a patchwork of the most sumptuous textiles in favor in Central Asia during the 19th century. Magnificent examples of ikat, specially dyed silk weavings, alternate with appliqué and embroidery, some of it in couched gold and silver thread. The windows are elaborate geometric cutouts edged with gold—a far cry from the woven reed screens that would have originally served that purpose. The inner roof has similar panels of different textiles, while the outer roofs and awnings are boldly striped in red, yellow, black and white. The brilliance of the colors and the splendid workmanship make the St. Petersburg tent one of the most remarkable still in existence.

The Hermitage in St. Petersburg has an earlier tent, which had seen a good deal of use before someone in the Russian army acquired it in the early 19th century. Because of its coloring, it is believed originally to have belonged to a middle-ranking officer. Even so, the decoration is exquisite, and though the tent is somewhat worn and far less eye-catching than the emir's gift tent, it remains a more elegant production.

The Central Asian tents reached India with various waves of conquerors, culminating with Babur (1483-1530), who laid the foundation of the Mughal Empire. The yurt-type tent with its heavy outer layer largely vanished in the warmer climate and was supplanted by the marquee. In keeping with the general luxury of the Mughal court, the most splendid fabrics were often used. The poet Abu al-Fazl, for example, mentions many-colored materials from China, Anatolia and Europe.

Numerous descriptions of the tents by local chroniclers and foreign visitors make it clear that, as in Central Asia, they were often pitched in a garden or a place where some particularly beautiful scenery could be enjoyed. The accounts also show that tents were sometimes preferred even when a splendid palace was available. Indeed, many of the buildings in the royal city of Fatehpur Sikri in Rajasthan have rings in the great courtyards which are believed to have served as tie-downs for tent ropes. This was partly personal preference and partly a political statement emphasizing the rulers' connection to a military and nomadic past stretching back to Timur and Genghis Khan. In the Arab world, of course, tents evoke memories of the tribes and the early days of Islam. Even today, the Libyan leader Muammar al-Ghaddafi makes a statement by his use of tents in public and private contexts—most recently in 2009 in suburban New York.

|

| VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM / ART RESOURCE. |

| A printed, painted and dyed cotton tent-hanging from the Mughal Dynasty almost brings nature inside. It dates to the early 18th century. |

Babur's daughter, Gulbadan Begum, had this to say about tents: "The covering of the pavilions and of the large audience tent was, inside, European brocade, and outside Portuguese cloth. The tent poles were gilded; that was very ornamental…. [My lady] had prepared a tent-lining … of Gujrati cloth of gold." She also describes six shamianas, or ceremonial tents, of gold brocaded broadcloth, each of a different color, set up to welcome her at Agra on a visit to her father during his last years.

According to Sir Thomas Roe, the English ambassador to the Mughal court from 1615 to 1618, the emperor's tents "walled in, about halfe an English mile in compasse in the forme of a fort." On a different occasion, Roe mentions the walls or screens made of panels of pintadoes—hand-painted chintz—or of red embroidered cloth at a time when the color red was still reserved for the ruler.

Indeed, the Mughal Empire in India raised the art of the tent to new levels of splendor: Timur's 12-pole tent described by Clavijo was far surpassed by Humayun's Zodiac Tent, in which the 12 signs were worked in precious stones, and by Akbar's vast and carefully planned tent-palace. The window of the tent of Nur Jehan, favorite wife of Jahangir, the fourth Mughal emperor, was screened with a gold medallion set with pearls and gems and golden bars or chains. (On the other hand, Roe mentions that in more ordinary tents, woven reed was still being used for windows, and he makes note of ladies breaking away the cane mesh in order to see better.)

When Nadir Shah seized power from the Mughals in India in 1738–1739, he inspected the treasury at Delhi and reportedly said: "It is by no means an act of wisdom to leave the property of the world unused." Among other things, he ordered for himself a great tent made of the finest violet-colored satin decorated with flowers and beasts made of gold and precious stones. The tent poles and fittings were of pure gold, and the curtains that divided off the private quarters were worked with a pair of beautiful angels. The tent could be taken apart and packed in special boxes carried by several elephants—but some parts were so heavy with gold that even the elephants had trouble carrying them. The tent was, it seemed, intended to complement Shah Jehan's Peacock Throne, another of Nadir Shah's spoils.

This fascination with tents extended to Europe, where rulers, including Louis xiv of France, had tents copied in Ottoman or Mughal styles. The British in India adopted them for ceremonial occasions, and in 1876 a vast shamiana—red of course—was commissioned for Queen Victoria's coronation as Empress of India. And today, shamianas, often of chintz or appliqué, are still regularly used in India for weddings and similar occasions.

|

| SAMIA EL-MOSLIMANY / SAWDIA |

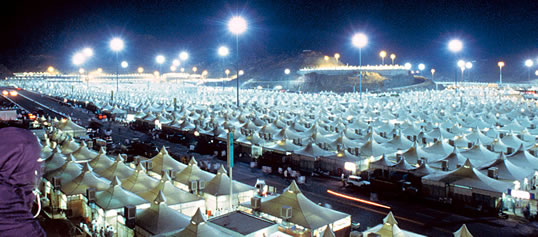

| A neatly arrayed city of 40,000 tents is provided by Saudi authorities each year for Muslims making the pilgrimage to Makkah. It recalls—and exceeds in size—the tent cities that amazed western visitors to Muslim lands in the Middle Ages. |

The history of tents and tent cities does not, however, end in the 19th century. Today, the largest tent city of all time is in modern use annually at Mina, just outside Makkah. There, Saudi Arabia shelters about two million pilgrims who come each year to perform the Hajj, or pilgrimage. The orderly rows of some 40,000 custom-designed white tents offer a level of comfort available in the past only to a privileged few. The design and positioning of the tents is a matter of great complexity, since space is limited, ritual schedules are tight and the numbers of people to be accommodated vast: The tent city of the Hajj represents an achievement that surpasses even those that so amazed travelers in centuries past.

|

Caroline Stone divides her time between Seville and Cambridge, where she is senior researcher on the Civilizations in Contact Project (www.cic.ames.cam.ac.uk). |