|

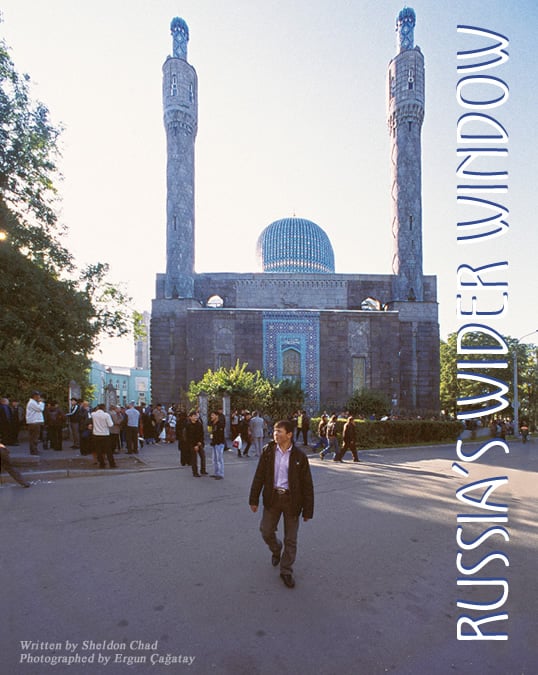

| The mosque combines decorative motifs from Central Asia with a main building styled in the Northern Art Nouveau that was popular in Europe during the first years of the 20th century. |

|

In front of me are 300 years of remarkable history. Closest is the Peter and Paul Fortress, the kernel from which this imperial city grew, and, within it, the golden-spired Peter and Paul Cathedral, which holds the tombs of the Romanov czars. Farther along is the berthed battle cruiser Aurora, which fired the first shot of the 1917 October

Revolution. In between rise the mosaic-topped minarets of the Central Asian-style St. Petersburg Cathedral Mosque. Its 49-meter (157') minarets and its tiled azure dome appear to nestle next to the spires of the fortress. It has been 100 years since the mosque’s cornerstone was laid—but what a century it has been.

One of the northernmost mosques in the world and, until the 1990’s, the largest in Europe (it’s now number four, with the top three also in Russia), it serves as a hub for Muslims in St. Petersburg, who are estimated to number between 500,000 and one million in a metropolitan population of some five million.

|

| A park separates the mosque from the Neva River and, at far right, the Peter and Paul Cathedral, where the Romanov czars are buried. |

|

| Craftsmen from Central Asia drew on their architectural history to produce the mosque’s elaborately decorated portals. |

“Russia is a Russian Orthodox country. It is an Islamic country,” says Mikhail Piotrovsky. “Islam is part of our history, and the Islamic population is part of

our population.

“My profession is an Arabist,” Piotrovsky says. “Being director of the Hermitage [State Museum] is a hobby.” He is being modest: He is a scholar, with a reputation as one of the world’s most efficient museum managers.

“Understanding itself as an empire, Russia had two very important things built in St. Petersburg in the beginning of the 20th century,” Piotrovsky continues. “A Buddhist temple and the mosque. So it was, let us say, a historical presence and an imperial understanding of what the capital of an empire is.”

The cupola of the St. Petersburg Mosque is a near-replica of the Gur-e Amir—Tamerlane’s tomb—in Samarkand, says Piotrovsky, but the main body of the mosque is built in Northern Art Nouveau, the style popular

in St. Petersburg and the Baltic states from the late 1890’s to the early years of the

20th century.

“So that’s how it comes together: It was a cultural event. It’s not just a present or a [public] relations [gesture] to Muslims. It’s a cultural situation of Islam being part of Russian culture, traditionally, for many, many years.”

“So that’s how it comes together: It was a cultural event. It’s not just a present or a [public] relations [gesture] to Muslims. It’s a cultural situation of Islam being part of Russian culture, traditionally, for many, many years.”

Move across the Neva onto Vasilievsky Island to the Kunstkamera, Russia’s very first museum, where Peter the Great hoped all Russians would “acquire full knowledge of the world.”

|

|

| sheldon chad (2) |

| Top: One of several early designs for the mosque, this one, which was not built, dates from 1906. Above: Among guests of honor at the laying of the mosque’s cornerstone on February 3, 1910, was the Emir of Bukhara (center), who not only bought the land for the mosque, but also convinced Czar Nicolas ii that the site near the Romanov tombs, far from being inappropriate, in fact demonstrated Muslims’ “loyalty to the Russian Empire.” |

“We have a proverb: ‘Scratch a Russian, find a Tatar,’” says Efim Rezvan, deputy director of the museum, now called the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography. Rezvan’s finds on the historic ‘Uthman Qur’an are celebrated, and he’s busy with preparations for a new expedition to Kazakhstan. “Tatar” was the term the Russians coined for all the ethnicities, principally Muslim ones, that descended from the Golden Horde and the Turkic peoples.

“My name is Rezvan, which is ‘Rizvan,’ and Rizvan is the angel who holds the keys of the Muslim Paradise. As far back as my family remembers, we are Orthodox Christians, but my surname indicates for sure that one of my ancestors was Muslim of Turkish or Persian origin,” he explains. “If you think Rachmaninoff, the composer, reflects the Russian spirit, trace his surname—Rachman. Where did he come from? Muslims! So everybody is in Eurasia, one foot in Europe and one in Asia.

“And we have the same story in St. Petersburg,” says Rezvan, “because when Peter the Great decided to establish the new capital, he invited the whole country to build it, and groups of Tatars from the Volga region came here. These were the first Muslims who came to the banks of the River Neva.”

It was Peter the Great, says Rezvan, who “set the stage for the systematic study of the Muslim East.” Peter also personally ordered the first Russian version of the Qur’an; it was published in 1716 in St. Petersburg. Six years later, publication of The System Book or the State of the Muhammedan Religion required the development of an Arabic typesetting capability. Once that was available, Peter started issuing proclamations in Arabic.

So St. Petersburg’s Muslim history—and Russia’s related history with Muslims, by way of imperial orders coming from the imperial capital—goes back to the city’s beginnings 300 years ago, since when there has been a continuous Tatar presence in

So St. Petersburg’s Muslim history—and Russia’s related history with Muslims, by way of imperial orders coming from the imperial capital—goes back to the city’s beginnings 300 years ago, since when there has been a continuous Tatar presence in

the city.

“I think the St. Petersburg Mosque is now one of the symbols of the city,” says Rezvan. “There is no panorama of the center of St. Petersburg that does not show two minarets. And this symbol is not only of St. Petersburg. This reflects the country itself, and the dramatic history of the mosque reflects the dramatic history of the country.”

n April 23, 1906, the Public Committee for the Construction of the St. Petersburg Mosque held its first meeting. By then there were 15,000 Muslims in St. Petersburg, divided equally between civilians and military personnel.

n April 23, 1906, the Public Committee for the Construction of the St. Petersburg Mosque held its first meeting. By then there were 15,000 Muslims in St. Petersburg, divided equally between civilians and military personnel.

There had been a checkered history of previous attempts by the Muslims of St. Petersurg to build a mosque as their population grew, but Czar Nicolas ii’s proclamation of religious freedom on April 17, 1905 gave the project new impetus.

More than 20 years earlier, in one of those attempts, community leaders had started collecting money, but by the time of the czar’s proclamation, they had raised just 53,000 imperial rubles. Minutes of the meeting reported, “If we are as successful raising money in the future as we’ve been in the past 20 years, Muslims will get their mosque no earlier than the next century!” So they needed a new money-raising idea.

Luckily, they also had a new man—

their newly chosen chairman, Abd al-Aziz Davletshin.

|

| As many as 23 nationalities, from the length and breadth of the Russian Federation and abroad, gather for congregational prayers in the

St. Petersburg Mosque each Friday. Until the 1990’s, the mosque was the largest on the European continent; today, it is the fourth largest. |

Davletshin was both a Tatar nobleman and a czarist general. Later he would head the Asiatic department of the military general staff. Eight years earlier, in 1898, as a staff captain, he had been sent by order of St. Petersburg on an “important Arabian trip”—that is, he was sent on the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Makkah, not as a pilgrim, but as a spy. At the time, Makkah and Madinah were in the hands of the Ottoman Turks. Rezvan, who has written a book in Arabic on Davletshin, says that “his most important idea was that the position of Muslims in Russia was much better than people in the East thought.” The upshot was that Russia began giving Muslim pilgrims to Makkah the same rights and the same official help that it extended to Orthodox Christian pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem.

Within two months under Davletshin, the committee received permission from internal affairs minister Pyotr Stolypin to build a mosque, and permission to solicit funds for the purpose not only in St. Petersburg but from all over Russia. Within a few more months, the committee had raised 142,000 rubles and found what they thought was a reasonable, affordable plot of land. But they soon discovered it was too small for a mosque properly oriented toward Makkah. Purchasing the adjoining plot of land could remedy this, but more than doubled the price.

Davletshin called on a friend, Said Abdul Ahad Khan, emir of Bukhara (now in Uzbekistan), who was close to Czar Nicolas ii. The emir stepped up and bought both properties on the community’s behalf.

A design competition was then announced in an architectural magazine. Out of 45 projects entered, that of Russian architect Nikolai Vasiliev won. His design evoked the famous Samarkand Gur-e Amir, but in St. Petersburg, the outer walls would be built of the Finnish gray granite typical of the city, and the dome would slope more steeply so as not to accumulate heavy snow.

On December 14, 1908, the mosque committee submitted blueprints to the city planning committee, which approved them and sent them on to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The ministry passed them on to the Academy of Arts, which held approval authority for large civic constructions.

As the committee prepared to break ground in the spring of 1909, anticipating approval, a small newspaper article reported the planning committee’s approval of the mosque on the site next to the Peter and Paul Fortress. Tatar historian and tour guide Almira Tagirdzhanova explains that the committee never imagined that having their mosque close to Christian sites would create a backlash.

“The Orthodox church authority was against that land being bought by the Muslims,” says Tagirdzhanova. “The Orthodox newspaper Kolokol [The Bell] wrote that ‘if the Muslim “church” were built, a disaster would befall Russia.’ I joke in my excursions, ‘Maybe that was what brought about the Revolution!’”

By April 1909, the Internal Affairs Ministry seemed to be sitting on the decision. Stolypin, who was now prime minister, remained mum. Because approval was taking so long, the committee suspended its work plans. At last the decision came from the Academy of Arts: They said no.

The Academy report judged the mosque too large and the land too wide open for it to be built so close to the Peter and Paul Fortress, the Trinity Church and Peter the Great’s house. It would, the Academy wrote, “destroy the historical and aesthetic character of this part of the city.”

This touched off popular opposition: Another newspaper editorialized ,“They would be screaming from the minarets. The call to prayer would disturb other churches around.”

Davletshin demanded that Stolypin intercede, and the emir of Bukhara dropped in for a personal visit to the czar. “It’s time to start building the mosque, even next to the Peter and Paul Fortress, where the czars are buried,” said the emir. “For Muslims to build in that place especially shows their respect for and pride in the royal family and their loyalty to the Russian Empire.”

The czar got the message, says Rezvan. “At the turn of the century, after huge Muslim territories were added to the Russian Empire, the authorities decided that a great mosque should be here. St. Petersburg had the prime Orthodox Cathedral, then the Choral Synagogue was the synagogue for all Jews. The Buddhist datsan in St. Petersburg was the datsan for all Buddhists. The czar had to have in the imperial capital the main temples of all the communities. That’s politics.”

Stolypin sent the Academy’s report back to the ministry committee—possibly with instructions—which overruled the Academy, saying the mosque committee had acted according to all the rules for any house of prayer, and that, as the land was privately owned, no law existed to prevent construction.

On June 27, 1909, Stolypin met with the czar and received final approval.

he morning of February 3, 1910 was gray, with snow on the ground. At the site of the mosque, a makeshift wooden prayer room had been erected with a little cupola on top.

he morning of February 3, 1910 was gray, with snow on the ground. At the site of the mosque, a makeshift wooden prayer room had been erected with a little cupola on top.

At 11:00, the inauguration ceremony for the new mosque began before an overflow crowd. The emir of Bukhara was present, as were a host of dignitaries from the government, the military and the Muslim party in the Duma, or congress, and the ambassadors from Turkey and Persia.

|

| From the city’s founding in the early 18th century until the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1989, St. Petersburg’s Muslim population never exceeded 50,000. (At the 1910 opening of

the mosque, it was about 7300.) Now, however, migrants from former Soviet republics and from elsewhere in the Russian Federation comprise as much as 20 percent of St. Petersburg’s population. Among them, many run small businesses such as this grocery store. |

Akhun Ataulla Bayazitov, writer, scholar and former imam of the military, led the prayer and then gave a speech. “Our mosque is beautiful, but that it should be beautiful on the outside is not enough. We should pray to [God] that all of us here will achieve beauty on the inside.”

Construction was slow, and Russians today often say, “All is divided by the Revolution.” The next decade would be the most turbulent in Russia’s history: It brought World War i, the 1917 October Revolution and the 1917–1923 civil war. Though the first prayers were held in the unfinished mosque on February 22, 1913, in commemoration of the 300th anniversary of the Romanov Dynasty, construction took a full decade. And when the Cathedral Mosque was officially opened on April 30, 1920, it was just as gosateism (“state atheism”) was being officially invoked, calling for all things religious to be dismantled. To be a besbozhnik (“godless person”) was among the highest values of a revolution that saw religion as “the opiate of the people.”

At the time, the imam, or prayer leader, of the new mosque was Musa Bigi, who served until his arrest in 1923. Bigi at first supported the Bolshevik revolution, but then one of its leaders wrote a book called The ABC of Communism. Bigi replied with his own book, The ABC of Islam, and was jailed for it. Only the intervention of Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Atatürk saved him, and he later escaped

to exile.

The mosque was still open in 1924, when Lenin died and Petrograd—as the city had been called since World War i—was renamed Leningrad, but the congregation had dwindled to a few, and the government rented out storage space in the building for potatoes, fruits and vegetables and even tombstones. Muslims complained that the humidity of the produce was destroying the building. In 1936, the mosque was put on notice that it would be closed if the congregation did not repair the damage, especially the deteriorating mosaics, but it was impossible at the time to find the money to comply. Year after year the Russian authorities called for “immediate” restoration until, in 1940, the city decided to close the mosque and do the restorations itself. The outbreak of World War ii changed that plan.

atiana Stetzkevich, now 82, remembers her childhood in Leningrad in the 1930’s. “We had a janitor who was a Tatar. He got married and the celebration went on for three days. During that time his bride was sitting on pillows, her face covered. All the people in our housing block celebrated with them, Russians, Germans, Poles, Swedes.”

atiana Stetzkevich, now 82, remembers her childhood in Leningrad in the 1930’s. “We had a janitor who was a Tatar. He got married and the celebration went on for three days. During that time his bride was sitting on pillows, her face covered. All the people in our housing block celebrated with them, Russians, Germans, Poles, Swedes.”

Stetzkevich is the curator of eastern

religions at the Museum of the History of Religions, which from 1932 until 1989 (and when she joined in 1954) was known as the Museum of Religion and Atheism. Like all Russians her age, she lived through “the difficult Soviet times.”

During World War ii, while still a young girl, Stetzkevich survived the infamous

872 days of the Nazi siege of Leningrad, during which more than 1,500,000 civilians starved. She shows me the medal she received for working at a factory eight hours a day, seven days a week. It reads:

For our Soviet Patriotism

For the Defenders of Leningrad

1942

Stetzkevich, who is not Muslim, speaks about the Muslims’ role at that time in a film she narrated, “Faith During the Siege.” “Muslims could still practice all the rituals at home,” Stetzkevich says, “but because of hunger, they didn’t fast during Ramadan or feast on Kurban Bayram [‘Id al-Adha].

“When people died, they would still try to bury them with all the rituals in the Muslim cemetery, but as the numbers swelled and their strength gave out, they would just be buried in mass graves. When it became difficult even to bring the bodies to the cemetery, they brought them to hospitals, brought children to their school or kindergarten. Not just Muslims. Everybody did.

“The very difficult time was the beginning of the siege when the Germans bombed all the storehouses and would sink any ships coming to try to break the blockade. When finally they did break it, by trucks going over the ‘Road of Life’ [the ice route across frozen Lake Ladoga], it became easier. In ’42 and ’43, Muslims again could come together to pray.”

Through the entire Soviet period, says Stetzkevich, “It’s my own opinion that Muslims, more than followers of other religions, retained their religious traditions. In the practice of Islam, the only public ritual you do is to come to the mosque; everything else you can practice at home. The person who was Communist in public could practice Islam at home and nobody would know about it.

“It was, somehow, easier to be a Muslim,” she adds. “The main focus of the Soviets’ ideological war was against Christianity in general, especially evangelical Protestants and Orthodox,” she says. “In the museum, Islam wasn’t even shown, and there was no propaganda against Islam.”

The war and its toll of more than 20 million dead somewhat moderated the Soviet repression of religion. Returning Muslim war veterans petitioned for a place to pray in Leningrad. In 1949 alone, they wrote more than 20 letters, but that same year, the mosque was given over to the Hermitage as a place to exhibit the museum’s oriental collections. Muslims then asked to buy a former Polish cathedral, but managed to secure only a portion of the cemetery for burial rites. In 1953, they again asked for the mosque to be returned to them, because it was still being used only for storage. Historian Tagirdzhanova cites an internal document by a city official that sums up the sentiment at the time: “I don’t see any reason to give the mosque back to the Muslims because the mosque is located in the center of the city and next to the Kirov Museum and the Museum of the Revolution [in the Peter and Paul Fortress].” The note also reported, however, that from spring to fall, Muslims by the hundreds prayed outdoors, next to the mosque.

randfather came to the closed mosque. He was to open it and organize the Muslim community of Leningrad,” says Gumer Isaev, director of the St. Petersburg Center for Modern Middle East Studies and grandson of Mufti Abd-ul-Bari Isaev, who served as mufti (leader) of the St. Petersburg Mosque from 1955 to 1973.

randfather came to the closed mosque. He was to open it and organize the Muslim community of Leningrad,” says Gumer Isaev, director of the St. Petersburg Center for Modern Middle East Studies and grandson of Mufti Abd-ul-Bari Isaev, who served as mufti (leader) of the St. Petersburg Mosque from 1955 to 1973.

In 1929, as a young man, Mufti Isaev was imprisoned in the anti-Muslim backlash of the time, and he spent two years in a gulag. During World War ii, he was wounded in the battle of Stalingrad.

In 1955, Isaev recounts, Indian statesman Jawaharlal Nehru visited Russia and spent two days in Leningrad. Having seen the blue cupola of the mosque from his motorcade and recognizing its similarity to the one he had seen in Samarkand, he asked to visit it, but was told it was closed.

The following March, the Supreme Soviet issued an order to the Ministry of Religion and Culture that, to accommodate international delegations visiting the Soviet Union, all help should be given to the new imam Isaev. His task was to restore and reconsecrate the mosque; the near-dormant Muslim community too had to be reintegrated and recentered on the mosque.

|

| These days, the full prayer hall each Friday gives few hints of the decades during which gosateism, or “state atheism,” deterred worship not only at the mosque, but also at religious institutions of all kinds throughout the Soviet Union. |

Indonesian President Sukarno was invited to visit the city in October 1956. “The just-opened Leningrad mosque was added to his itinerary,” says Isaev. “The mosque was used to show that there was Islam in Russia. It was a very important ideological point.”

Particularly because Mufti Isaev coordinated Islamic activity for all of Russia from 1973 to 1980, the Isaev family’s own generational stories say much about spiritual life from the latter half of the Soviet period to today.

“Father said that Grandfather didn’t want him to follow his path. He said that it’s very complicated and not easy to be a mufti under the Soviets.” As a result, Gumer’s father, Gali Isaev, grew up to become a communications engineer for the Buran space shuttle program in Kazakhstan in the 1980’s.

“Father was not very religious. But

we were trying not to forget that my grandfather was a mufti, so we were not quite so assimilated here in Leningrad,” says Isaev.

The mufti died when Gumer was only four, but he left Gumer a legacy. “After his death,” says Gumer, an Arabic-language magazine “came for many years to our flat. I asked Father what is written here, and he told me, ‘In the future you will study Arabic, and you’ll read these magazines and will know what is written there.’

“My father wanted me to follow the way of Grandfather. He wanted, I think, that my future would be connected with the Muslim world,” he says. “My dream is to write a book about Grandfather, together with my father, about the period of his work here in Leningrad. There is no information about the first steps, about how the mosque was opened in 1956. We have many documents and papers written by Grandfather, but they are all written in Arabic script in the Tatar language.”

“My father wanted me to follow the way of Grandfather. He wanted, I think, that my future would be connected with the Muslim world,” he says. “My dream is to write a book about Grandfather, together with my father, about the period of his work here in Leningrad. There is no information about the first steps, about how the mosque was opened in 1956. We have many documents and papers written by Grandfather, but they are all written in Arabic script in the Tatar language.”

(Before the revolution, Tatar was written using Arabic characters, but in the 1930’s, the alphabet used was changed, first to Latin and then to Cyrillic, the same

letters used for Russian.)

“My father speaks Tatar but he can’t read Arabic. And I can read Arabic but I have poor knowledge of Tatar. So only together can we translate.”

|

| Outside the mosque, Mufti Ponchaev leads prayers for a funeral. Between World War ii and 1956, Muslims were frequently buried near a former Polish cathedral. |

or 35 years I have been the head of the mosque. That is a third of the mosque’s life and half of my own life,” says Mufti Djafar Nasibullovich Ponchaev, 70, whose leadership at the mosque followed Isaev’s and bridges the end of the Soviet era, the period of perestroika, and today’s Russian Federation.

or 35 years I have been the head of the mosque. That is a third of the mosque’s life and half of my own life,” says Mufti Djafar Nasibullovich Ponchaev, 70, whose leadership at the mosque followed Isaev’s and bridges the end of the Soviet era, the period of perestroika, and today’s Russian Federation.

When Ponchaev, who was born in Penza in Siberia, some 1600 kilometers (1000 mi) east of St. Petersburg, started his studies in Bukhara, it was in what was then the lone madrassa, or Islamic school, in the whole of the Soviet Union.

Explaining Muslim life in the Soviet Union, Ponchaev says, “The official version in this country was that religion doesn’t exist. Islam either.” But in fact, back in 1971 in Bukhara, the Soviet Union held a celebration of Muhammad al-Bukhari, the famous poet, Ponchaev says. There were delegations from Muslim countries and all parts of the Soviet Union. “The representative of Saudi Arabia saw more local Muslims than he expected, in spite of such

”he says. “He was really touched. When he spoke, it brought tears to his eyes.”

|

| Restored in recent decades by volunteers and donors who included Christians and Jews, the St. Petersburg Mosque has become a social as well as spiritual center for the city’s Muslims. |

After 1975, during Leonid Brezhnev’s time, “control was eased,” says Ponchaev.

When Ponchaev took charge of the mosque in the 1980’s, much of the tile from the dome had fallen onto the roof, damaging both it and the ceiling below.

“St. Petersburg had as its first vice president of city administration Mikhail Filonof. He is Russian. He is Christian. He is Communist,” says Ponchaev. “One early morning in summertime, I was sitting here, and he came and spoke to me.” Filonof informed Ponchaev that, later that morning, there would be a meeting at which it would be decided to close the mosque permanently. Filonof then inspected the mosque and afterward told Ponchaev, “If you dropped a bomb on it, it would probably survive; your ancestors built it well.”

Then Filonof said, “In this meeting, everybody will be in agreement to close the mosque. I will give you the last word, and you should say, ‘I thank you very much. I really appreciate what you’re doing. I take full responsibility for whatever will happen to the mosque should it not be closed.’ And then I will immediately adjourn the meeting.” The fix, Ponchaev realized, was in.

|

| A postcard captioned in both Russian and French shows the mosque shortly before the 1917 October Revolution, indicating that even in its earliest years, the mosque was regarded among the city’s landmarks. |

“Imagine,” says Ponchaev, still a bit baffled after all these years, “He’s from the city administration, and in that period it was not in his interest to help me. Christian. Communist. Atheist.”

Ponchaev did as he had been told,

Filonof adjourned the meeting, and once again, the mosque was saved. Today, a plaque beside the building extols the contributions of government—Russian leader Vladimir Putin is mentioned along with former St. Petersburg mayor Anatoly

Sobchak—and private donors, including both Christians and Jews who contributed to the mosque’s most recent renovation, completed in 2003.

|

| The mosque’s chandelier hints at the blending of Islamic and Art Nouveau design. |

“This is how the beauty of the mosque works to help us,” says Ponchaev, adding, “Thank God, we have ordinary people giving just to maintain the building.” In addition to the monetary donors, he says, hundreds of men and women of all ages worked without recognition to maintain the mosque and make it functional again. Coming in on their days off, they removed garbage, cleaned the building, made repairs and brought gifts of carpets.

“My life is in this building, with this building,” says Ponchaev. “And I say now it is a ship which will never sink. My main hope is that it will never be closed again.”

He has a new young assistant, Imam Tahsin Nalınlı, from Istanbul. Nal?nl? teaches Arabic and the Qur’an to some 30 students and, in return, they teach him Russian.

tep out of the Gorkovskaya metro station at Friday prayer time and you feel as though you’re in a crowd going to a sporting event, as hundreds and hundreds of people walk the couple of hundred meters to the mosque. Over the treetops, the sky-blue mosaic of the minarets and the turquoise cupola sparkle in the sun. As you enter the gates of the mosque, there are already Uzbek and Tajik women selling savory baked samsas and cigarettes. Behind you is St. Petersburg, but with the Central Asian-style mosque in front of you, its façades decorated in verses from the Qur’an in Arabic calligraphy, you can be forgiven for feeling far, far to the east.

tep out of the Gorkovskaya metro station at Friday prayer time and you feel as though you’re in a crowd going to a sporting event, as hundreds and hundreds of people walk the couple of hundred meters to the mosque. Over the treetops, the sky-blue mosaic of the minarets and the turquoise cupola sparkle in the sun. As you enter the gates of the mosque, there are already Uzbek and Tajik women selling savory baked samsas and cigarettes. Behind you is St. Petersburg, but with the Central Asian-style mosque in front of you, its façades decorated in verses from the Qur’an in Arabic calligraphy, you can be forgiven for feeling far, far to the east.

|

| Men socialize on the grounds of the mosque on Friday after prayers. |

At the Friday prayers, I see quickly that the purpose of this building was not only to be beautiful, though it is that. Packed with 1500 to 2000 people, it is fulfilling its original promise as a center for the religious life of the city.

The blue mosaic mihrab, or prayer niche, is bathed in blue light. Blue on blue, it is glorious. I see the lofty interior—the columns of green marble, the large dome, daylit now, filled with a chandelier inscribed with verses of the Qur’an. The assistant imam leading the prayers has a honeyed voice, and among the prayerful there is another beauty that mesmerizes more than the building does: the faces. Twenty-three nationalities, from the length and breadth of Russia and abroad, who have all come to St. Petersburg, many in the last 20 years as immigrants from the former Soviet republics, all pray here as one with the descendants of their “Tatar” predecessors, as they have always done in St. Petersburg. The spoken words are in Arabic, Russian and Tatar. The hats are traditional Tatar square-sided ones and the white kadis (skullcaps) worn by those who have been to Makkah on the Hajj. But again, my eyes return to the faces—Uzbek, Afghan, Ingushetian, Asian; from the Pacific, Europe, the Arctic, the Black Sea; Russian faces, African faces, Pakistani faces and even Arab faces. In those faces, more than anywhere else, it seems that Akhun Bayazitov’s prayer at the mosque’s founding a century ago is being answered: “Our mosque is … beautiful on the outside. …We should pray to [God] that all of us here will achieve beauty on the inside.”

St. Petersburg is no longer a window on Europe alone, but a window on a far wider world.

|

Sheldon Chad (shelchad@gmail.com) is an award-winning screenwriter and journalist for print and radio. From his home in Montreal, he travels widely in the Middle East, West Africa, Russia and East Asia. |

|

Writer and photographer Ergun Çağatay lives in Istanbul. He is the co-editor and photographer of The Turkic Speaking Peoples: 2,000 Years of Art and Culture from Inner Asia to the Balkans (Prestel). |