|

| james p. blair / ngs image collection |

| A 17th-century traveler estimated there were more than 3000 pigeon towers near Isfahan, and today some 250 to 300 survive in various states of decay. Though many look alike, no two are precisely the same. |

Written by Eric Hansen

ate one summer day, I was seated in a local bus as it rumbled through open fields and orchards on the outskirts of Isfahan, Iran. Lurching down the hot, dusty road, while my fellow passengers napped, I looked out the window and saw in the distance what appeared to be four or five ancient mud-brick watchtowers falling to ruin.

ate one summer day, I was seated in a local bus as it rumbled through open fields and orchards on the outskirts of Isfahan, Iran. Lurching down the hot, dusty road, while my fellow passengers napped, I looked out the window and saw in the distance what appeared to be four or five ancient mud-brick watchtowers falling to ruin.

But as the bus drew closer, I noticed the towers didn’t have crenellated battlements or loopholes in

the upper walls for rifles. Moreover, open farmland seemed an oddly exposed placement for any sort of fortification. Standing nine to 12 meters high (30-40'), these plastered, dun-colored towers looked like giant chess pieces.

|

| arthur thevenart / corbis |

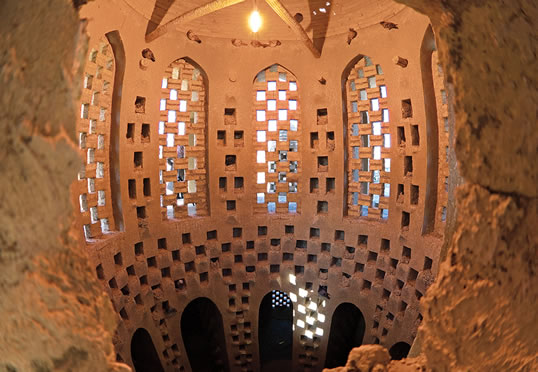

| An abandoned tower shows a typically honeycombed interior that could house 5000 to 7000 pigeons. To the birds, the towers offered refuge from nocturnal predators. |

We drove into the city, leaving the towers behind, but I continued to wonder about their purpose. Were they ancient grain silos? Abandoned charcoal kilns? Or perhaps they had been built to catch cooling late-afternoon breezes and provide well-to-do landowners with shade and scenic views over parklands and lush gardens that no longer existed. My imagination went to work on other possibilities, but as it turned out, none of my far-flung guesses proved to be correct.

Only recently, after reading about the excellence of Persian melons and the elaborate gardens and fortifications of Isfahan in The Travels of Olearius in Seventeenth-Century Persia, by the German scholar Adam Olearius, did I eventually discover that these structures were pigeon towers dating back to at least the Safavid Empire (1502-1736). Especially noteworthy are the towers built during the rule of Shah Abbas the Great (1571-1629), who made Isfahan his capital.

Though Olearius did not mention pigeon towers, his account led me to later observations by the Frenchman Jean Chardin in his Voyages en Perse et autres lieux de l’Orient. Traveling in Persia from 1673 to 1677, Chardin described how the towers were built to attract huge flocks of wild pigeons, numbering in the thousands. He estimated there were more than 3000 pigeon towers in and around Isfahan. An earlier European traveler, Thomas Herbert, in his book Travels in Persia 1627-29, compared the sophistication of pigeon-tower architecture to domestic household architecture in this way: “… their houses … were in no wise comparable to their dove-houses for curious outsides.”

Given the number of towers (called kabutar khan in Farsi) and their size and architectural sophistication at the time of Chardin’s observations, it seemed reasonable to assume that the pigeon towers of Isfahan in fact considerably predated the Safavid Empire. Lending support to this theory, Hafiz-i Abru stated, in his 15th-century work Majma’ al-Tawarikh (Compilation of History), that Ghazan Khan (1271-1303), the seventh ruler of the Ilkhanid Dynasty, “has banned hunting near the towers to protect the pigeons.”

The typical pigeon tower of Isfahan is cylindrical outside, constructed of unfired mud brick, lime plaster and gypsum. Large towers range from 10 to 22 meters in diameter (33-72') and stand 18 or more meters high (60').

The typical pigeon tower of Isfahan is cylindrical outside, constructed of unfired mud brick, lime plaster and gypsum. Large towers range from 10 to 22 meters in diameter (33-72') and stand 18 or more meters high (60').

Pigeon towers are common in the fields surrounding Isfahan, but are very rarely seen in other parts of the Iranian plateau where conditions are less favorable for large populations of birds. Situated 1590 meters (5216') above sea level and with ample water from the Zayandeh-Rud River, which flows year-round out of the Zagros Mountains, the Isfahan oasis provided an ideal habitat for wild pigeons and large-scale agriculture.

I assumed the pigeons were kept for their meat, but this was apparently not the case. Marco Polo, the famous 13th-century traveler, claimed that the Persians didn’t eat pigeons because they

“ hold them in abhorrence.” Herodotus, writing some 1700 years earlier, commented that Persians disliked the taste of the birds, though young pigeons—squabs—are well known to be delicious and succulent.

Another possible explanation of why the Persians abstained has to do with the belief that pigeons were held to be sacred because of their association with the Prophet Muhammad. During the earliest years of Islam, tradition has it that a fantail pigeon (baba kooh) perched and fed on the Prophet’s shoulder as he preached. In a similar vein, people of medieval Europe believed in the sacredness of doves and refrained from eating them because of their association with Christian tradition.

But still further research revealed the real purpose of the towers: They were designed to collect pigeon dung, which has a high nitrogen content and is a boon for Isfahan’s nitrogen-deficient soil. Pigeon droppings are also rich in phosphorus, another fertilizing agent. The dung was used to fertilize fruit trees, as well as the legendary cucumber and melon fields of Isfahan.

Chardin wrote that pigeon dung, when mixed with soil and ash, was tehalgous, or “enlivening,” according to the Persians. The resulting combination of trace elements provided similar ratios of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium to those found in modern-day fertilizers. Applied at the standard rate of 900 grams (2 lbs) per fruit tree per year and approximately 1680 kilos per hectare (1500 lbs/acre) annually, the dung increased the harvest by as much as 50 percent.

|

| rahmin dehdashti / iranpix |

| Its elegance transcending its utilitarian purpose, this tower, above and below, is one of about 65 that have been listed as protected structures. The inward slant of the interior wall of pigeonholes ensured that the dung fell to the bottom of the tower for collection. |

|

| rahmin dehdashti / iranpix |

By rough calculation, a large pigeon tower of that time may have contained 5000 to 7000 pigeonholes. On average, one pigeon produces 2750 grams (6 lbs) of dried dung per year, which translates into approximately 16,500 kilos (36,300 lbs) of high-quality fertilizer per large tower per year. Under optimal conditions, such a tower could thus provide enough fertilizer for more than 18,000 fruit trees or nearly 10 hectares (24 acres) of cropland, and was therefore a very valuable source of income for a village or the individuals who built and maintained it. Pigeon dung was in fact crucial to agricultural production and helped make it possible to feed the urban population of Isfahan, which numbered approximately 500,000 people at

the time.

Pigeon dung was also used in the legendary leatherworking shops of Isfahan. Mixed with water, it becomes muriate of ammonia (NH4Cl), which acts as an important softening agent in what is called “bating”—the final step before the actual tanning process.

More importantly, the dung was an essential ingredient in the manufacture of gunpowder, which consists of approximately 75 percent potassium nitrate (saltpeter), 10 percent sulfur and 15 percent carbon. The shah’s army had no natural source of potassium nitrate, but was able to manufacture it using a mixture of pigeon dung, ash, lime and soil. The process of making gunpowder was widely known in the Middle East by 1280, when Hasan al-Rammah, a Syrian, provided 107 recipes for gunpowder and described how to purify saltpeter in Kitab al-Furusiyyah w’ al-Manasib al-Harbiyya (The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices).

The wild rock pigeon (Columba livia) was by far the most common pigeon inhabiting the towers. The birds were not captured and trained to occupy the towers—rather, they were instinctively attracted to them because they replicated the rocky ledges and crevices in which pigeons like to nest, mate and rear their young in the wild.

The birds were provided housing, but not food. The flocks of pigeons went out to seek water and to forage during the day. At night the birds would return to the pigeon towers where they were safe from raptors, mammals, snakes and other predators.

They nested in a checkerboard pattern of closely spaced niches that covered the entire interior surface of the towers, which slanted inward slightly toward the top. The pigeonholes measured approximately 20 by 20 by 28 centimeters (8 x 8 x 11"), with a short projecting perch made of dried clay set at the opening of each one. The inward-slanting tower walls allowed pigeon dung to fall directly into a central collection pit at the foot of the tower, where it dried. The towers were opened once a year to harvest the dung that, in the 17th century, sold for a bisti, or four British pence, per 5.5-kilogram measure (12 lbs). A small tax was paid to the shah.

The checkerboard arrangement of pigeonholes made efficient use of space, maximizing the number of holes and keeping the weight and the amount of building material used in the tower to a minimum. The interior walls were further strengthened with the multiple uses of interior arches, barrel-vaulted ceilings, circular staircases and both interior and exterior buttresses. Little if any wood was used in the construction of the towers and, despite the long tradition of building the towers, no two are exactly alike.

Modern-day chemicals used in fertilizers, leather tanning and the manufacture of gunpowder eventually made the use of pigeon dung, and thus the pigeon towers, obsolete. Today, perhaps 250 or 300 towers remain in and around Isfahan. Abandoned, they continue to deteriorate due to lack of maintenance. Sixty-five of them are now nominally protected by their inclusion on the National Heritage List.

Even in their tumbledown state, the pigeon towers that remain are still impressive to see. Small flocks of wild pigeons occasionally roost in the towers, despite collapsed ceilings and huge cracks in the walls that expose the roosts to the weather. The view upward from the bottom of a tower reveals a sculptural quality and haunting beauty that transcend its utilitarian purpose as a place to collect the dung of wild birds.

The pigeon towers are an important part of Iran’s architectural heritage. Beyond the preindustrial mud-brick engineering that so efficiently solved complex structural problems with a perfect marriage of form and function, they remain as an enduring tribute to the ingenuity of unknown master builders who have left their unique creations for all to see, still standing on the fields of Isfahan.

|

Eric Hansen (ekhansen@ix.netcom.com) is a free-lance writer and photographer based in California. He is the author of numerous books, including The Bird Man and the Lap Dancer (2004), Orchid Fever (2001), Motoring with Mohammed (1992) and Stranger in the Forest (1988). |