Written by David James

alligraphy is without doubt the most original contribution of Islam to the visual arts.

For Muslim calligraphers, the act of writing—particularly the act of writing the Qur'an—is

primarily a religious experience. Most western non-Muslims, on the other hand, appreciate the

line, form, flow and shape of the Arabic words. Many recognize that what they see is more

than a display of skill: Calligraphy is a geometry of the spirit.

The sacred nature of the Qur'an as the revealed word of God gave initial impetus to the great

creative outburst of calligraphy that began at the start of the Islamic era in the seventh

century ce and has continued to the present.

Calligraphy is found in all sizes, from colossal to minute, and in all media, from paper to

ceramics, metal, textiles and architecture. It commenced with the writing down of the Qur'an

in a script derived from that of the Nabataeans. The early scripts were bold, simple and

sometimes rough. The scripts used from the seventh to the 11th century had origins in the

Hijaz, the region of Makkah and Madinah in western Saudi Arabia. Historians group these into

three main script families: hijazi, Kufic, and Persian Kufic.

Hijazi is regarded as the prototypical Qur'anic script. It is a large, thin variety with

ungainly vertical strokes. Kufic developed in the eighth century, and of all the early scripts,

it is the most majestic—a reflection of the stability and confidence of the early classical

period of Islam. It was much used through the 14th century from Islamic Spain all the way to

Iran, where around the 10th century calligraphers developed Persian Kufic. The system of marking

Arabic's normally implied short vowels and employing distinguishing dots, or points, is essentially

that used today in modern standard Arabic.

|

|

calligraphy samples by mohamed zakariya, reprinted from the art of the pen (london, 1996),

courtesy of the nour foundation |

Western scholars and students have often used the term "cursive" to distinguish later, less

angular scripts. However, medieval Muslim writers on calligraphy and the development of writing

classified scripts other than Kufic into categories based not only on shape, but also on function:

murattab, meaning curvilinear, primarily comprised scripts for courtly and secular uses, including

thulth, tawqi' and riqa'; yabis, or rectilinear scripts, comprised styles for Qur'anic and other

sacred calligraphy, including muhaqqaq, naskh and rayhan. These are often regarded as the six major

"hands" of classical Arabic calligraphy.

As well, there were regional varieties. From Kufic, Islamic Spain and North Africa developed

andalusi and maghribi, respectively. Iran and Ottoman Turkey both produced varie-ties of scripts,

and these gained acceptance far beyond their places of origin. Perhaps the most important was

nasta'liq, which was developed in 15th-century Iran and reached a zenith of perfection in the

16th century. Unlike all earlier hands, nasta'liq was devised to write Persian, not Arabic.

In the 19th century, during the Qajar Dynasty, Iranian calligraphers developed from nasta'liq the

highly ornamental shikastah, in which the script became incredibly complex, convoluted and largely

illegible to the inexperienced eye.

The Ottomans devised at least one local style that became widely used: the extremely complex diwani,

which was well suited to expressing a complex language like Ottoman Turkish, itself a hybrid of

Turkish, Arabic and Persian. It was used much in official chancery documents and firmans, or decrees,

which often began with the most imposingly ornate calligraphic invention of the Ottoman chancery,

the imperial tugra, or monogram.

We do not know when the idea of a freestanding composition based on a word, phrase or letter first arose.

The first separate such calligraphic composition was perhaps the phrase bismillah al-rahman al-rahim ("In the Name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful"), which begins every chapter of the Qur'an but

one. Due to the imbalance of the letters, this turns out to be an awkward phrase to write well, and to

this day can be a test of the calligrapher's skill. The separate calligraphic composition reached its

ultimate development in the 18th and 19th centuries, at the hands of Iranian and especially Ottoman

calligraphers.

Such calligraphic composition became particularly important when calligraphy departed from paper

to appear on functional objects. Some of the finest examples of this occurred on 10th-century ceramics

from the Samarkand area. Simple inscriptions in classical Kufic, always in Arabic, were applied to

the rims of plates and dishes, usually pure white in color. The results, to western eyes at least,

represent some of the most esthetically pleasing and exciting examples of applied calligraphy.

But perhaps the most important application of calligraphy to objects is in architecture. Throughout

the Islamic world, few are the buildings that lack calligraphy as ornament. Usually these inscriptions

were first written on paper and then transferred to ceramic tiles for firing and glazing, or they were

copied onto stone and carved by masons. In Turkey and Persia they were often signed by the master, but

in most other places we rarely know who produced them.

We do know that such masters of calligraphy were often born to it. Once a young man's potential was

recognized, he would be apprenticed to perfect the basic hands, learn ink-making and perhaps study

paper-making and illuminating. When he was considered good enough to work on his own, he would receive

an ijazah, or license. Although in Europe the scribal profession disappeared soon after the arrival

of the printing press at the end of the 15th century, in the Middle East printing did not become

firmly established until the 19th century, and thus the profession of the calligrapher largely endured

until then.

Today, calligraphy continues as a religious and artistic practice. Outstanding calligraphers live throughout

the world, and their works bring the attention of the global public to the supreme art of Islamic calligraphy.

Written by Paul Lunde

It is he who made the sun to be a shining glory, and the moon to be a light (of beauty),

and measured out stages for her, that ye might know the number of years and the count (of time).

—The Qur'an, Chapter 10 ("Yunus"), Verse 5

The Hijri calendar

In 638 ce, six years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad,

Islam's second caliph, 'Umar,

recognized the necessity of a calendar to govern the affairs of Muslims. This was first of all

a practical matter. Correspondence with military and civilian officials in the newly conquered

lands had to be dated. But Persia used a different calendar from Syria, where the caliphate was

based; Egypt used yet another. Each of these calendars had a different starting point, or epoch.

The Sasanids, the ruling dynasty of Persia, used June 16, 632 ce,

the date of the accession of the last Sasanid monarch, Yazdagird iii.

Syria, which until the Muslim conquest was part of the Byzantine Empire, used a form of the Roman

"Julian" calendar, with an epoch of October 1, 312 bce. Egypt used

the Coptic calendar, with an epoch of August 29, 284 ce. Although

all were solar calendars, and hence geared to the seasons and containing 365 days, each also had a

different system for periodically adding days to compensate for the fact that the true length

of the solar year is not 365 but 365.2422 days.

In pre-Islamic Arabia, various other systems of measuring time had been used. In South Arabia,

some calendars apparently were lunar, while others were lunisolar, using months based on the

phases of the moon but intercalating days outside the lunar cycle to synchronize the calendar

with the seasons. On the eve of Islam, the Himyarites appear to have used a calendar based on

the Julian form, but with an epoch of 110 bce. In central Arabia, the course of the year was

charted by the position of the stars relative to the horizon at sunset or sunrise, dividing

the ecliptic into 28 equal parts corresponding to the location of the moon on each successive

night of the month. The names of the months in that calendar have continued in the Islamic

calendar to this day and would seem to indicate that, before Islam, some sort of lunisolar

calendar was in use, though it is not known to have had an epoch other than memorable local events.

There were two other reasons 'Umar rejected existing solar calendars. The Qur'an, in Chapter 10,

Verse 5, states that time should be reckoned by the moon. Not only that, calendars used by the

Persians, Syrians and Egyptians were identified with other religions and cultures. He therefore

decided to create a calendar specifically for the Muslim community. It would be lunar, and it

would have 12 months, each with 29 or 30 days.

|

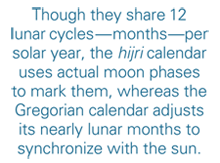

This gives the lunar year 354 days, 11 days fewer than the solar year. 'Umar chose as the epoch

for the new Muslim calendar the hijra, the emigration of the Prophet Muhammad and 70 Muslims

from Makkah to Madinah, where Muslims first attained religious and political autonomy. The hijra

thus occurred on 1 Muharram of the year 1 according to the Islamic calendar, which was named

"hijri" after its epoch. (This date corresponds to July 16, 622 ce on the Gregorian calendar.) Today in the West, it is customary, when writing hijri dates, to use the

abbreviation ah, which stands for the Latin anno hegirae,

"year of the hijra."

Because the Islamic lunar calendar is 11 days shorter than the solar, it is therefore not

synchronized to the seasons. Its festivals, which fall on the same days of the same lunar

months each year, make the round of the seasons every 33 solar years. This 11-day difference

between the lunar and the solar year accounts for the difficulty of converting dates from

one system to the other.

The Gregorian calendar

The early calendar of the Roman Empire was lunisolar, containing 355 days divided into 12 months

beginning on January 1. To keep it more or less in accord with the actual solar year, a month was

added every two years. The system for doing so was complex, and cumulative errors gradually misaligned

it with the seasons. By 46 bce, it was some three months out of alignment,

and Julius Caesar oversaw

its reform. Consulting Greek astronomers in Alexandria, he created a solar calendar in which one day

was added to February every fourth year, effectively compensating for the solar year's length of

365.2422 days. This Julian calendar was used throughout Europe until 1582 ce.

In the Middle Ages, the Christian liturgical calendar was grafted onto the Julian one, and the

computation of lunar festivals like Easter, which falls on the first Sunday after the first full

moon after the spring equinox, exercised some of the best minds in Christendom. The use of the

epoch 1 ce dates from the sixth century, but did not become common

until the 10th.

The Julian year was nonetheless 11 minutes and 14 seconds too long. By the early 16th century,

due to the accumulated error, the spring equinox was falling on March 11 rather than where it should,

on March 21. Copernicus, Christophorus Clavius and the physician Aloysius Lilius provided the calculations,

and in 1582 Pope Gregory xiii ordered that Thursday, October 4, 1582 would be followed by Friday,

October 15, 1582. Most Catholic countries accepted the new "Gregorian" calendar, but it was not adopted

in England and the Americas until the 18th century. Its use is now almost universal worldwide. The

Gregorian year is nonetheless 25.96 seconds ahead of the solar year, which by the year 4909 will add up

to an extra day.

| Converting Dates |

| The following equations convert roughly from Gregorian to hijri and vice versa.

However, the results can be slightly misleading: They tell you only the year in which the other

calendar's year begins. For example, 2012 Gregorian begins and ends in Safar, the second month,

of Hijri 1433 and 1434, respectively. |

| Gregorian year = [(32 x Hijri year) ÷ 33] + 622 |

Hijri year = [(Gregorian year - 622) x 33] ÷ 32 |

| Alternatively, there are more precise calculators available on the Internet:

Try www.rabiah.com/convert/ and www.ori.unizh.ch/hegira.html. |

|

Paul Lunde (paullunde@hotmail.com) is currently a research

associate with the Civilizations in Contact Project at Cambridge University. |