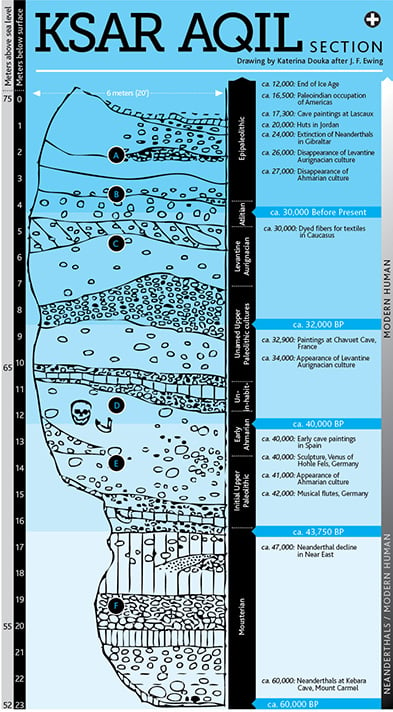

Among prehistoric archeologists, Ksar Aqil has an almost mythical status, but the site is little known outside professional circles. With layer upon layer of prehistoric tools, animal bones and fire pits, dating from between 60,000 and 15,000 years ago, it is one of the most continuously and intensively occupied Old Stone Age sites in the Levant and, perhaps, the world. The migration of modern humans out of Africa and the Near East’s position as a bridge between continents and cultures, as well as nearly a century of scientific research, are all woven into the story of Ksar Aqil.

|

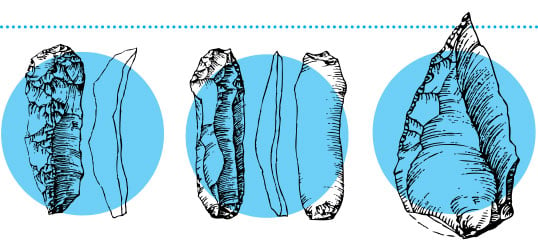

| An “Ahmarian” people, whose culture lasted 14,000 years, from roughly 41,000 to 26,000 years ago, lived at Ksar Aqil. From excavations at the site, archeologists have recovered thousands of projectile points, scraping tools and knives. |

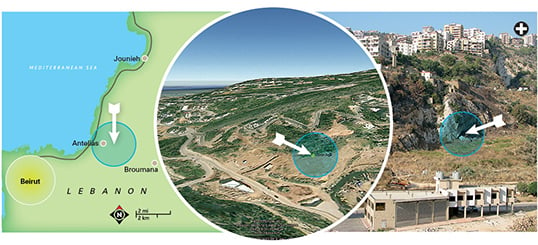

Although spanning a prehistory of tens of thousands of years, Ksar Aqil only entered the historical record in the 1920’s, when the owners of the site started digging for treasure under an overhang set in a high limestone cliff. This overhang, nestled in the foothills of the Lebanon Mountains near the present-day town of Antelias, northeast of Beirut, formed what archeologists call a rock shelter. The attempt to find gold and silver was unsuccessful, but the diggers unwittingly discovered one of the Near East’s most important Paleolithic sites.

Although spanning a prehistory of tens of thousands of years, Ksar Aqil only entered the historical record in the 1920’s, when the owners of the site started digging for treasure under an overhang set in a high limestone cliff. This overhang, nestled in the foothills of the Lebanon Mountains near the present-day town of Antelias, northeast of Beirut, formed what archeologists call a rock shelter. The attempt to find gold and silver was unsuccessful, but the diggers unwittingly discovered one of the Near East’s most important Paleolithic sites.

The discovery of artifacts at Ksar Aqil that were suspected to be the handiwork of ”cave men“ prompted naturalist Alfred Day of the American University of Beirut to examine the site in 1922, the year that also witnessed the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb by Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon. Prospecting in the treasure hunter's pit, at the back wall of the rock shelter, Day recovered some 2000 flint and bone artifacts. Word of the discovery eventually filtered out of the region to the foremost authority on Paleolithic cave art, the Abbé Henri Breuil of the Collège de France, who proposed that the site be examined in more detail.

In 1937, a small team of Jesuit archeologists followed the Abbé Breuil’s advice and began fieldwork. The expedition was led by 33-year-old Father Joseph Doherty from Boston College in Massachusetts, then a student at Cambridge University under the grande dame of Near Eastern prehistory, Dorothy Garrod. Other participants included paleoanthropologist Father J. Franklin Ewing, later of Fordham University, as well as Fathers George Mahan and Joseph Murphy of the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Jerusalem. During the excavations, the physical labor of which was undertaken by a Lebanese workforce, an astonishing 23 meters (75') of rock-shelter deposits were shoveled, sifted, and sorted.

|

| Hadi Choueiry |

| Sheltered from the north winds and facing roughly southeast, Ksar Aqil lies between the coast and the mountains. This location offered inhabitants protection and an abundant variety of resources. |

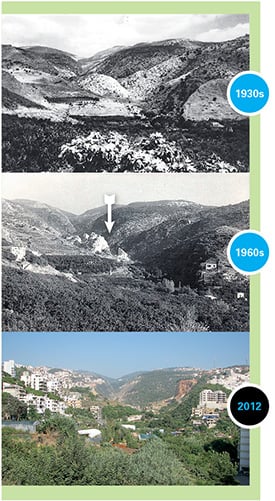

Father Doherty was not prepared for his encounter with the Lebanon of the 1930’s—or with Ksar Aqil, which he visited for the first time on April 4, 1937. Just two days later he wrote that “the valley of Antelias in the vicinity of the site is about the wildest country I have ever seen. Recall pictures you have seen of the wilds of Afghanistan, and the Northwest Indian Frontier near the Khyber Pass—e g., in ‘Lives of a Bengal Lancer’—and you have a fairly accurate picture.”

Two months after arriving at the site, the Jesuits had erected a dig house with work areas, a wash room, kitchen and sleeping quarters for six. They employed upward of 30 local workers who earned 50 piasters a day performing such manual labor as excavating and sieving the sediments for artifacts. The volume of excavated material soon reached overwhelming proportions, prompting Doherty to comment that “only a Jesuit would ever think of undertaking a work of this magnitude on a grant of $1750 [$28,000 in today’s money], inclusive of travel and living expenses…” The eminent French Jesuit paleontologist and geologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who offered guidance to the young Jesuits excavating Ksar Aqil in the 1930’s and 1940’s, wryly remarked, “You started for a student’s work and you are facing a man’s job.”

The Boston College excavations uncovered several million artifacts, a staggering number for any prehistoric archeological site. These are predominantly made of flint, a raw material ubiquitous in the limestone bedrock of Lebanon, but they also include large numbers of butchered animal bones, marine shell beads, bone and antler projectile tips and awls, various decorated objects, and ochre colorant. Not surprisingly, this treasure trove of Paleolithic artifacts has taken almost 90 years to describe fully, but these studies have not exhausted the site’s potential. Corine Yazbeck of the Lebanese University hopes to continue fieldwork in the future, noting, “Ksar Aqil is the most significant prehistoric site in Lebanon and it contains the longest sequence of Upper Paleolithic occupations in the Near East.”

Current perspectives on human evolution and mankind’s colonization of the globe are based upon fossil evidence, as well as excavated artifacts and biogenetic data. These lines of inquiry indicate a relatively recent evolution of modern humans, Homo sapiens sapiens, in Africa about 200,000 years ago.

The latest, and arguably most powerful, analytical tool available to those investigating human origins comes from molecular biology. Geneticists have found that examination of the DNA from tiny structures inside the cell, called mitochondria, provided a means to measure human biogenetic relationships on a time scale spanning hundreds of thousands of years. Mitochondria, also known as the powerhouse of the cell because they generate chemical energy, possess their own genome, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is inherited exclusively from the mother.

Dramatic results released in 1987 by researchers at the University of California at Berkley indicated that mtDNA sequences in African populations display the greatest diversity. African peoples, such as the Kalahari San, possess the most ancient genetic lineages on the planet: They have accumulated evolutionary changes over the longest period of time. The study postulated that all mtDNA present in people today stems from a single female who lived about 200,000 years ago in Africa. This woman was called “Mitochondrial Eve,” the genetic mother of all of Earth’s present-day population.

Tens of thousands of years before Beirut became a meeting place of East and West, the Levantine coastal strip and the Arabian Peninsula to the south were corridors through which our common ancestors moved out of Africa and into Asia, Europe, Australia and, lastly, the Americas. The region also has the distinction of being a place where Neanderthals (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) and our immediate ancestors co-existed and indeed interbred.

|

From top to bottom: archive of dorothy a. e. garrod;

henri fleisch/levon nordiguian; hadi choueiry |

| Viewed from what is now Antelias to the west, the limestone hill sheltering Ksar Aqil’s has been quarried nearly flat since the first excavations. |

The evolutionary split between Neanderthals and the ancestors of modern humans occurred sometime between 440,000 and 270,000 years ago. The Neanderthals, the cave men of popular literature, lived in Europe, south into the Levant, and as far east as Iraqi Kurdistan and southern Siberia. According to research conducted by Svante Pääbo at Leipzig’s Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, a little Neanderthal DNA, between one and four percent, exists in all peoples alive today, except for those in Africa. It is probable that our Neanderthal heritage resulted from interbreeding that happ ened in the Near East sometime between 80,000 and 45,000 years ago.

According to proponents of the “out of Africa” theory, the exodus of anatomically modern humans probably occurred in waves. One early migration into the Near East occurred prior to 130,000 years ago, and an examination of a modern map of the Horn of Africa and adjacent parts of Arabia shows there are two obvious routes this migration could have taken. One involves crossing from northern Egypt into the Sinai Peninsula, the other crosses the Bab el-Mandab strait to reach modern-day Yemen, perhaps by watercraft. It is likely that both these routes were taken at different times, as they were navigable, presented no significant hazards and were frequented by the animals our early ancestors tracked and hunted. Given the geographic position of the Near East as a bridge between Europe and Asia, this region formed the trunk through which our family tree branched out from its African roots, both geographically and genetically.

|

| Overview of the excavation area and upper levels. |

|

| Excavator exposing a well-preserved deer antler. |

|

| Examples of Levantine Aurignacian bone and antler points. |

|

| The skull of seven-year-old Egbert, as found during excavation. |

|

| Initial Upper Paleolithic (iup) blade tools include chamfered pieces and burins, or chisels. |

|

| The excavation team reaches approximately 19 meters (62') in depth. |

|

|

John Shea of Stony Brook University described the interaction between Neanderthals and modern humans in the Near East as a geographic “tug-of-war,” with periodic movements by both populations into and out of the region. When modern humans entered the area over 130,000 years ago, the Neanderthals were in residence, and it seems they curtailed the extent of the newcomer’s settlement for a while. When another wave of modern humans began migrating from Africa about 50,000 years ago, perhaps due to population pressure on resources and territory, our ancestors ultimately became the sole inhabitants of places like Ksar Aqil.

If this contest had been based on physical strength alone, the Neanderthals would have won hands down. Modern humans, however, had developed cognitive, physical and cultural abilities that provided an advantage, ultimately leading to the Neanderthals being relegated to geographically marginalized refuges.

Neanderthals differed from modern humans in a number of ways, perhaps most noticeably in their skull anatomy, which featured a sloped forehead, a large projection at the back of the skull called an occipital bun, pronounced eyebrow ridges, and no chin. Physically robust and more powerfully built than our ancestors, their massive but relatively short stature was more efficient in cold climates like Europe’s.

Examination of inner-ear fossils in Spain suggests Neanderthals could hear a similar range of sounds to people alive today. The anatomy of their throat, specifically the presence of a hyoid bone, gave them the ability to articulate sounds beyond mere grunts.  In common with modern humans, they possessed a gene essential for language development, and some paleoanthropologists believe they were capable of complex speech patterns. However, a model Neanderthal vocal tract, aided by a computer to create a probable range of sounds, has led Robert McCarthy of Florida Atlantic University to conclude that they lacked complex language. Whatever the case may be, the voices of the Neanderthals have now been silent for at least 24,000 years.

In common with modern humans, they possessed a gene essential for language development, and some paleoanthropologists believe they were capable of complex speech patterns. However, a model Neanderthal vocal tract, aided by a computer to create a probable range of sounds, has led Robert McCarthy of Florida Atlantic University to conclude that they lacked complex language. Whatever the case may be, the voices of the Neanderthals have now been silent for at least 24,000 years.

The Neanderthals apparently were not suited to activities like long-distance running. The energy cost of locomotion was apparently 32 percent higher in Neanderthals, resulting in a daily dietary requirement between 100 and 350 calories greater than that of modern humans living in similar environmental settings. Our ancestors may, therefore, have had a competitive edge simply by being more fuel-efficient.

Evidence from the Iberian Peninsula indicates that Neanderthals used decorative ochre pigments, and at Shanidar Cave, in Iraqi Kurdistan, analysis of plant pollens in soils surrounding skeletal remains suggests that wildflowers were placed on the bodies of the dead. Body ornamentation and ritual burial practices, albeit somewhat simple, represent behavior identical to that of modern humans.

|

| british museum |

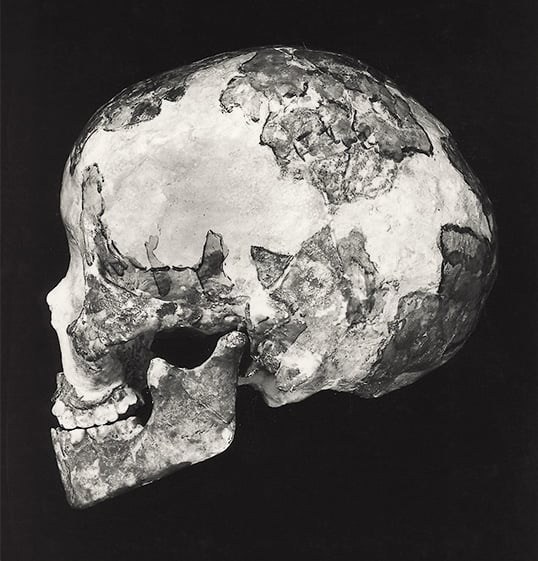

| Egbert’s skull was reconstructed by J. F. Ewing in 1955, as shown in this University of Pennsylvania plaster cast. The original skull lay at a level estimated to be about 40,000 years old. |

What exactly happened to the Neanderthals no one knows. Modern peoples migrating into Southwest Asia and on to Europe may have displaced them. Undoubtedly, contact led to a variety of interactions, some clearly resulting in opportunities for interbreeding, others—such as those described in William Golding’s book The Inheritors—involving physical conflict and competition for resources. The Neanderthals’ demise may also have been linked to rapid climatic swings between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago, which created further pressure on their already divided and isolated populations.

Ksar Aqil is best visualized as a layer cake with 23 meters of superimposed occupational levels spanning a 45,000 year period. The earliest layers are Middle Paleolithic and, although never dated, they are probably some 60,000 years old. At that time, Neanderthals still roamed the Near East, but they were not alone. Our ancestors were undergoing resurgence in the region, and it may be that both groups used the rock shelter on different occasions. Who was responsible for the Ksar Aqil Middle Paleolithic artifacts remains a mystery, since both Neanderthals and modern humans used the same methods for making stone tools.

The Middle Paleolithic levels are followed by a long succession of Upper Paleolithic occupations, unquestionably the lengthiest sequence in the Near East. During the 1937-1938 excavations, Father Doherty identified 18 such occupation levels. Later investigations at the site by the eminent French prehistorian Jacques Tixier, based on refined stratigraphic divisions, demonstrated that the actual number of levels is many times that count.

On August 23, 1938, the Boston College excavators uncovered the rarest of finds, anatomically modern skeletal remains, under a pile of water-worn rocks at a depth of 11.46 meters (about 38'). A September 1938 letter from Father Doherty to the president of Boston College indicates the degree of excitement: “This comes to you in a whisper, Father—we probably have two skeletons, for we have in addition to the skull and skeleton already mentioned, a lower jaw of another youthful Aurignacian.” Doherty had every right to be excited: Early Upper Paleolithic human fossils remain scarce in the Near East even today, numbering just a handful of specimens.

The two individuals were found lying next to one another. One skeleton was poorly preserved and encased in a compacted deposit, while the other was lying partly outside this tightly consolidated area, which made recovery easier. Named “Egbert” by the excavators, the better preserved remains have been identified by Christopher Stringer of the British Museum of Natural History as belonging to a child who died at about seven years of age. Recently, Katerina Douka of Oxford University’s Research Laboratory for Archaeology dated marine shell beads recovered from the same level as Egbert to 40,000 years ago.

Doherty did not believe the two children were deliberately buried, writing that “it seems that the poor youngster or youngsters were thrown on a kitchen midden with no more care than that given to the remains of wild boar, bear, and deer....” However, the placement of the remains at the back of the shelter, under a pile of rocks, does seem to suggest a simple, but deliberate, interment. The fact that the bodies were kept within the confines of the habitation, a place undoubtedly important to Egbert’s people, further suggests a desire to keep cherished individuals in close proximity.

Egbert belonged to a group of hunter-gatherers known to archeologists as Ahmarian, situated throughout the region between 41,000 and 27,000 years ago. The name Ahmarian refers both to the archeological site Erq el-Ahmar, near Bethlehem, where this prehistoric culture was first recognized, and to the fact that these people utilized a red ocherous colorant (ahmar means “red” in Arabic) for decorative purposes. It is not known exactly what kind of social organization the Ahmarians practiced or how they interacted with one another on a daily basis.

But studying the behaviors of modern hunter-gatherers is one way to understand how prehistoric peoples may have behaved. Ethnographic analogy, though speculative, offers a window into the ways of life of ancient cultures that have long ago disappeared. We suspect the Ahmarians lived in family-related groups, as modern-day hunter-gatherers do. Band societies are egalitarian, semi-nomadic to highly mobile, with loosely structured leadership based on clan and age. Among tribal groups like North America’s Lakota Indians or the Aboriginal Nyantunyatjara of Australia, men hunt while women and children gather edible plants, tubers, fruit and nuts, as well as trap small game animals. Gathering, based on women’s intimate knowledge of location and season, provides 50 percent or more of the band’s subsistence base. Such cooperative social behavior has been vital to our survival and, according to the late Glynn Issac of Harvard University, it stretches back millions of years.

|

| spring knower (4) |

| Using hammers made of organic materials like deer antler, Ahmarian peoples easily detached numerous thin blades by striking a single piece of flint. These were turned into hide-scraping tools, knives for cutting and projectile points for hunting. |

What is known for sure is that the Ahmarians were adept at working stone: They discarded thousands of their blade tools at Ksar Aqil. Blades are knife-shaped objects struck from shaped blocks of flint called cores, especially designed to promote an elongated, narrow shape. Although most frequently seen in later Stone Age cultures, like the Upper Paleolithic, they were made as early as 250,000 years ago at sites in the el-Kowm basin, northeast of Palmyra, Syria. Using hammers made of organic materials, like deer antler, Ahmarian peoples were able to detach numerous thin blades from a single piece of flint. These were turned into hide-scraping tools, knives for cutting and projectile points for hunting.

The Ahmarian hunters at Ksar Aqil made two different types of projectile points, both of them expediently manufactured and simple in design. Specifically, the tips of blades were sharpened to a point by chipping with a tool like a sharp antler tine. The blades, already thin as a result of the method of detaching them from the core, were ideally suited for setting into a shaft. The style of the projectile points made in different parts of the Levant suggests localized groupings of Ahmarian bands. In the northern coastal areas, they made a type of projectile called a flat-faced point that is not found further south in the desert regions of the Negev and Sinai.

We don’t know precisely how the points were used, but their size, shape and weight suggest the use of a spear thrower or perhaps even a bow. Experimental replication and use of the Ahmarian points from Ksar Aqil, called el-Wad points after Mugharet el-Wad in the Mount Carmel region, indicates they are extremely effective when launched as projectiles.

The technology for attaching stone tools to handles was known to Neanderthals as early as 110,000 years ago. They used heat-activated adhesives like bitumen or plant resins to place projectile tips on wooden shafts. The difference between the Neanderthal style of hunting and that of the later Ahmarians is that the former used a close-quarter thrusting spear. The disadvantage of this weapon is clear from its name: When hunting large game, the likelihood of injury is significant. As Erik Trinkaus of Washington University observed, Neanderthal skeletal remains frequently display trauma that most closely matches present-day rodeo bronco and bull riders. Specifically, there is a high incidence of head and neck injuries, suggesting close encounters with the large game they hunted.

The Ahmarians and other Upper Paleolithic peoples, on the other hand, probably used hunting equipment that allowed them to strike their prey from a considerable distance. A spear thrower, or atlatl, acts as an extension to the arm, creating a lever that allows a relatively lightweight projectile, called a dart, to be thrown with greater speed over longer distances.

Egbert’s people were very successful hunters: Massive amounts of animal bone have been recovered at Ksar Aqil from medium-sized game animals like fallow deer, roe deer, goat and gazelle. The manner of hunting probably involved solitary forays by individuals or small groups, stalking their prey or ambushing it. Analysis of the site’s faunal remains reveals there are smaller numbers of juvenile animals, indicating adults were most frequently exploited. Adult animals represent the greatest meat yield and are the highest-value targets for hunters.

What caused the death of Egbert and the other Ksar Aqil child is not known, but it is easy to imagine any manner of tragic childhood mishap, especially during those times. At age seven, Egbert was certainly a child by any standard, but life expectancy was short during the Upper Paleolithic, when reaching the age of 30 defined a long life. However, recent research suggests a dramatic increase in longevity took place among modern humans living during the same time as Egbert. The presence of increasing numbers of older members in a population provided socio-cultural benefits with clear advantages for survival.

At age seven, Egbert was certainly a child by any standard, but life expectancy was short during the Upper Paleolithic, when reaching the age of 30 defined a long life. However, recent research suggests a dramatic increase in longevity took place among modern humans living during the same time as Egbert. The presence of increasing numbers of older members in a population provided socio-cultural benefits with clear advantages for survival.

Most importantly, greater longevity meant modern humans were able to transmit acquired knowledge and experience directly from one generation to another. Increasing numbers of older adults also strengthened kinship bonds, as elders survived to provide social cohesion and guidance, much as grandparents do today. This, in turn, promoted population growth, since more individuals survived to ages where they could breed, and then lived on to support the reproductive success of their own offspring.

Ksar Aqil, with its south-facing opening, is situated in a sheltered valley with access to marine, coastal and upland resources. The coastal strip provided an avenue for movement, for exchange through trade as well as social interaction with related Ahmarian groups—as evidenced by markedly similar archeological materials recovered from different sites extending from Lebanon to southern Turkey. Indeed, Lebanon and the surrounding region have served as a conduit for commercial activity, as well as the transmission of ideas, science, art, and cuisine throughout recorded history. We now know that similar important contributions to the human story extend back tens of thousands of years. Further insights are certain to come as a result of new excavations in the Beirut area under the auspices of the Lebanese Directorate General of Antiquities.

Ksar Aqil’s location made it highly desirable for occupation, a fact attested to by its intensive and near-continuous use by some of Lebanon’s oldest citizens for approximately 45,000 years. Such a time span considerably dwarfs the longevity of other ancient civilizations found in the region, like those of the Phoenicians or the Romans. Phoenician ruins exist at locations like Byblos, while the site of Baalbek has some of the most imposing ruins outside of Rome itself. These archeological sites are iconic and readily recognizable to the interested public around the world, but Ksar Aqil has been much less visible.

Since the 1930’s, the limestone cliff has been largely quarried away. Lebanon has endured a period of civil upheaval and, in the process of rebuilding, the foothills surrounding Ksar Aqil have been heavily developed. Despite the burgeoning construction, the site remains an enduring witness to both the passage of time and the route modern humans used to populate our world.

|

Christopher Bergman (christopher.bergman@urs.com) graduated from the American University of Beirut in 1979 and completed his doctoral dissertation in 1985 at the Institute of Archaeology in London. He has spent 36 years pondering the archeological sequence at Ksar Aqil and believes he now understands the site, mostly.

|

Ingrid Azoury described the earliest Upper Paleolithic levels at Ksar Aqil. She has conducted investigations in Syria and Lebanon, notably at the rockshelter of Abu Halka, near Tripoli. |

Helga Seeden is a professor of archeology at the American University of Beirut. Her research interests include ethnoarcheology, which examines the lifeways of present-day traditional cultures as a means of interpreting events in the past. |