|

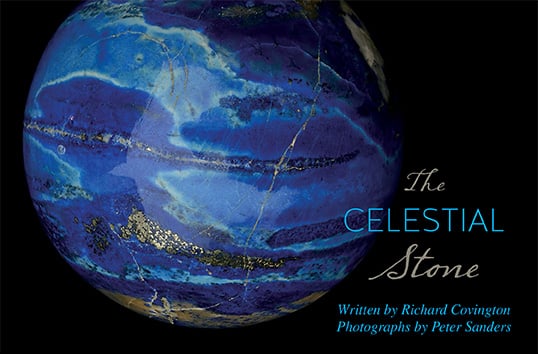

| Dominated by lazurite (from the Persian for “sky-blue”) and swirled with intrusions of calcite, sodalite and glittering pyrite, an 11-centimeter lapis lazuli orb in the Searight Collection, fashioned by artisan Arshad Khan, takes on a planetary appearance. |

he gem cutter bends over a whirring stone wheel, methodically shaving blue chips off a lump of lapis lazuli to shape a miniature heart. Maybe the piece will become a link in a necklace, maybe part of a pendant or perhaps one of a pair of earrings. It depends on the cutter’s inspiration: Khalil Mogbil is an artist first, a jeweler second.

he gem cutter bends over a whirring stone wheel, methodically shaving blue chips off a lump of lapis lazuli to shape a miniature heart. Maybe the piece will become a link in a necklace, maybe part of a pendant or perhaps one of a pair of earrings. It depends on the cutter’s inspiration: Khalil Mogbil is an artist first, a jeweler second.

“This is my artist’s cave,” he declares, pausing at his wheel and gesturing expansively around the small workshop in Idar-Oberstein, in the Rhineland region of western Germany, which also happens to be Europe’s gem capital. “Isn’t it a mess?” he laughs.

That it is: Shallow plastic buckets of rough stones litter the floor, and partially cut gems lie strewn across tables alongside motorized saws. Unfinished sculptures teeter on shelves. Powdery stone dust coats everything. Stepping gingerly over what looks like a large flower pot—it’s actually a tumbling machine for smoothing coarse stones—the 55-year-old craftsman fishes a squarish nugget of unpolished lapis from a pile of rocks.

|

| ChrISTIAn LArrIEU / brIDgEmAn ArT LIbrAry |

|

| CAIro mUSEUm / bIbLELAnDPICTUrES.Com / ALAmy |

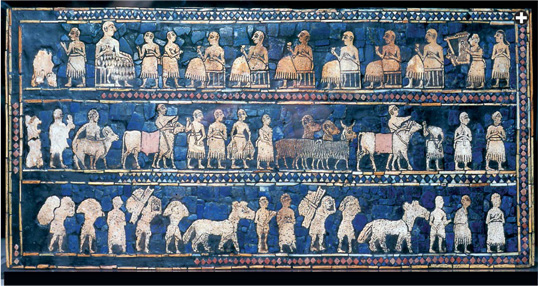

| Top: Lapis was prized in Egypt, where it was inlaid into the wings of this amuletic bird, shown above approximately three times its actual size. Above: In 2600 bce, Sumerian artisans cut lapis lazuli brought along trade routes from what is now Afghanistan to produce the background and decorative border of the Standard of Ur, whose inlaid figures were cut from shell. |

“That’s my trademark—the rough stone, where you can still see the texture,” he explains. “I don’t like polished stones, and besides, they’re too much work,” he grins. Since his necklaces sell for more than €1000 ($1350), it’s clear his unpolished style is favored by more than a few.

Mogbil is a former refugee from Soviet-occupied Afghanistan who learned his métier in Idar-Oberstein from his Afghan wife’s father and brother. Far from the land of his birth, he is erpetuating one of humanity’s most ancient craft traditions: Stonecutters have been fabricating lapis lazuli for more than seven millennia. Lapis ornaments dating from about 5500 bce have been uncovered at Neolithic graves in Mehrgarh, in the Baluchistan province of southern Pakistan. An oval pendant carved around 3300 bce was unearthed in Egypt at Naqada.

Sumerian kings, banqueting guests and musicians appear on the inlaid lapis lazuli background of a magnificent box known as the Standard of Ur, which was part of a Mesopotamian treasure trove dating from 2500 bce. In literature, the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh speaks of a chariot of gold and lapis lazuli.

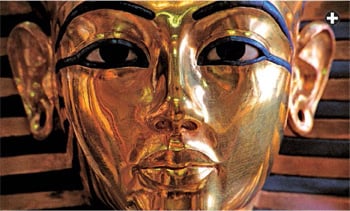

Some of the most sublimely crafted jewelry found in the tomb of Tutankhamun is adorned with scarab beetles made of lapis. Cleopatra wore eye shadow compounded from powdered lapis. The first-century Roman historian Pliny the Elder described the gemstone, with its flecks of iron pyrite (“fool’s gold”), as “a fragment of the starry vault of heaven.”

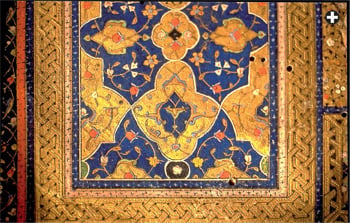

He wasn’t alone in his metaphor. Lapis has enhanced religious art from third-century Buddhist caves to 14th-century Russian Orthodox icons, Roman Catholic and Byzantine churches and Muslim manuscripts. Caliphs, authors and ladies of court wear lapis-hued robes in 13th-century manuscripts from Baghdad and Mosul. Lapis skies illumine painted heavens in churches from Istanbul and Venice to Bulgaria, Macedonia and Catalonia.

Renaissance masters like Giovanni Bellini, Titian and Albrecht Dürer insisted clients supply costly lapis pigment to produce the deep blue color considered suitable as background for images of the Virgin Mary, saints, celestial beings and popes. A principal reason for the Louvre’s restoration last year of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne was to bring out the original brilliance of Mary’s robe, tinted with lapis.

The blue jewel also links the craftsmen of Florence to the Mughal emperors of India. In the 16th century, a number of Italian artisans who had been trained in workshops founded by a Medici duke to produce inlays of pietra dura (“hard stone”) fashioned plaques of lapis and other gems for Shah Jahan’s Peacock Throne and for Queen Mumtaz’s tomb, the Taj Mahal.

In many lands and times, it was common for rulers and wealthy individuals to be buried with lapis mementoes as gifts for deities in the afterlife. Lapis was also valued for healing powers: Mogbil himself wears one of his own rough square beads around his neck, and he insists it helps lower his blood pressure. With its color the shade of a clear, even idealized cerulean sky, lapis has been regarded almost universally as the ultimate celestial stone, mined from dark earth to give rise to transcendent inspirations.

|

| Hemis / Alamy |

|

| Dick Doughty / Sawdia |

| Top: Lapis dates to the fourth century ce, but it had been used some 1700 years earlier in the funeral mask and many of the other treasures of Tutankhamun. Above: To European master painters, mughal miniaturists and illuminators of manuscripts, lapis paint was an important ingredient. |

Astonishingly, nearly all the world’s lapis lazuli comes from just one place: The blue-veined mountains enclosing the Kokcha River valley in the far northeastern province of Badakhshan, Afghanistan. Since antiquity, and throughout the period of the trans-Asian Silk Roads, the lapis mines were only accessible by camel, donkey and mule caravans. Even today, the precious rock continues to be transported out of the valley on pack mules and ponies, then by truck to Kabul, Peshawar and Karachi or overland into China. (Small amounts of lapis are mined in Siberia, Chile and Zambia, but the quality is generally inferior.)

Formed in the same tectonic thrust that pushed up the mountains of the Hindu Kush, lapis lazuli is a composite mineral, dominated by lazurite and mottled with traces of calcite, sodalite and pyrite. Lapis is the Latin word for stone, and lazuli is derived from lazhuward or lajuvard, Persian for sky-blue or azure.

Categorized as a semiprecious stone, lapis is considerably less valuable than precious gems such as diamonds, emeralds, sapphires or rubies. Low-quality raw lapis sells for as little as $5 a kilogram ($2.25/lb), but the purest lapis, which takes on a uniform, medium-blue color—one neither too dark nor too light, and without pyrite flecking—may bring upward of €10,000 per kilogram ($6150/lb), according to gem dealer Thomas Mohr of Idar-Oberstein. Mohr, whose family has been in the business for three generations, is occasionally commissioned to

engrave the highest-grade lapis for intricate, one-of-a-kind fantasias that sell for tens of thousands of dollars.

|

SmIThSonIAn InSTITUTIon /

nATIonAL mUSEUm, rIyADh |

| This simple cloaked figurine, found on Tarut Island in eastern Saudi Arabia, was carved from lapis sometime during the third millennium bce. |

The limpid blue stone is so highly prized by some that there are Hong Kong dealers who artificially dye low-grade lapis to hide streaks of impurities of gray and white calcite. Other buyers, of course, actually prefer calcite streaks because they give the impression of clouds or sea foam, while speckles of sparkling pyrite make for gold-on-blue color contrasts that fascinate the eye.

The discovery of lapis in archeological digs remote from its source has opened up new fields of inquiry about early trade routes. For example, a tiny lapis figure of a man wrapped in a cloak, five centimeters high (2"), was found in 1966 on Tarut Island off the coast of Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. (It is now in the National Museum in Riyadh.) It may have been carved there or, more likely, across the water in Iran, at Jiroft, in the third millennium bce. As early as 2400 bce, lapis was shipped from docks at Lothal, in India’s Gujarat state, across the Arabian Sea to Oman, Bahrain and Mesopotamia, according to historians Stephen Gosch and Peter Stearns in their 2007 book Premodern Travel in World History.

hether it was by caravan along the Silk Roads to Egypt,

Mesopotamia or Europe, by ship to Constantinople, Venice and Genoa, or today by air freight from Kabul to Idar-Oberstein to supply Mogbil, Mohr and other gem dealers, the geography of the lapis trade is a window into the history of artistic, commercial and political exchanges throughout Asia, Europe and North Africa.

hether it was by caravan along the Silk Roads to Egypt,

Mesopotamia or Europe, by ship to Constantinople, Venice and Genoa, or today by air freight from Kabul to Idar-Oberstein to supply Mogbil, Mohr and other gem dealers, the geography of the lapis trade is a window into the history of artistic, commercial and political exchanges throughout Asia, Europe and North Africa.

|

| brIDgEmAn ArT LIbrAry |

| Meticulously shaped fragments of lapis and other semiprecious stones, some smaller than the white part of a fingernail, are minutely composed to depict birds flitting among sprays of flowers and ribbons on the badminton Cabinet. Standing four meters—nearly 13 feet—tall, it was produced in Florence over six years in the 18th century by some 30 artisans. |

Both Mohr’s grandfathers were jewelers, and in the 1920’s both traveled to Afghanistan to obtain raw stone. Even then, Idar-Oberstein, which had been an agate-mining center

since at least the 16th century, prided itself as “the gem capital of Europe,” a title it still claims. The main streets are lined with stately homes, boutiques and modern office buildings catering to the jewelry trade. Visitors flock to the town of 30,000 inhabitants to explore the old agate mines and watch gems being polished on a traditional waterwheel, and they gape bedazzled at minerals, gems and ornaments from around the world in a pair of impressive museums.

Since the local agate was mined out by the end of the 19th century, the gem dealers and cutters were forced to branch out, first bringing in agate from South America and later adding other stones to their repertoires, including lapis. In the 1980’s, Afghan refugee jewelers like Mogbil escaped the Soviet invasion to Idar-Oberstein, where they set up workshops and supplied themselves with lapis with the help of relatives, friends and dealers back home. Eventually, craftsmen and dealers came also from Peshawar and elsewhere in Pakistan.

Unlike his grandfathers, who journeyed for weeks on trains, boats and mules to reach lapis dealers in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Mohr has his suppliers come to him. If he is running low, he calls up Afghan or Pakistani middlemen who maintain warehouses of the raw stone near Stuttgart, 150 kilometers (90 mi) to the southeast, and they negotiate prices and terms. “If I need less than 20 kilos [44 lbs] of medium-grade lapis—€400 to €1000 a kilo [$250-$610/lb]—I can have it within two days,” he says. Larger quantities or better-quality pieces take longer, but “if they don’t have what I want in their warehouses, they generally contact a relative or associate in Kabul or Peshawar and have him send it by air freight or deliver it in person,” Mohr explains.

Originally, Khalil Mogbil tried purchasing lapis in person at markets in Kabul and Peshawar, but he gave up because the dealers couldn’t be bothered to ship amounts less than 20 kilos. Instead, Mogbil, whose one-man operation uses less lapis than Mohr’s 10-person family business, often acquires raw lumps at gem and mineral shows in Germany and France.

|

| EmoTIonqUEST / ALAmY |

| Majestically crafted to give the impression it was carved from a single piece of lapis, the Badakhshan Vase towers 178 centimeters (nearly six feet) above visitors to the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. |

I first read about Mogbil, Mohr and Idar-Oberstein in a book titled Lapis Lazuli: In Pursuit of a Celestial Stone, written in 2010 by Sarah Searight, a London author and journalist who became so absorbed by lapis that she wrote a personal adventure tale of her peripatetic, 40-year exploration of the art, commerce and history of lapis. The search led her into markets, churches, monasteries, workshops, archeological sites, museums, libraries and archives across Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Russia, Central Asia, India and China.

Braced against an icy February wind, I sought out Searight at her home in the manicured south London suburb of Clapham. On the walls of her living room were paintings and textiles acquired over many seasons of traveling the Middle East, the Gulf countries and elsewhere, initially as a journalist for the International Herald Tribune, The Economist and other publications, and later as a lecturer and cultural travel guide. An Oxford history graduate, she earned a master’s degree in Islamic art at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies in the early 1990’s to deepen her appreciation of Middle Eastern culture.

“Then what do you do before you forget it all?” she asks me over tea and cookies. Her solution was to lecture about Islamic art across the uk and to lead tours in Egypt, Syria, Turkey and Central Asia. Since the groups invariably visited traditional markets, she always kept an eye out for lapis “to keep myself amused,” she says. She had no intention of publishing, she adds, until the Paris opening in 2006 of a touring exhibition of Afghan treasures.

“That’s when I said to myself: ‘All right, come on, get on with it and put together a book on lapis,’” she recalls with a wry smile.

Her long-standing fascination with lapis harks back to middle school, when she admired a poem by Robert Browning that dramatized a dying bishop’s last wish to be buried with a dazzling lump of lapis.

|

| InTErFoTo / ALAmy |

| In Bavaria, King Ludwig ii commissioned this ring of lapis, gold and diamonds for presentation to a duke. |

Some time later, when she asked an uncle who was a diplomat in India and Pakistan to bring her back a sample, he obliged. In her book, she recounts the vivid recollection of unwrapping a parcel of “grubby newspaper, out of which tumbled a small piece of rock as startlingly blue, I eventually came to find out for myself, as a starlit night sky or a sun-scorched day sky in the Hindu Kush.” It was, she wrote “a blue that pierced the senses.”

In 1973, Searight reached Afghanistan, accompanied by her husband and two small children. Venturing into Kabul’s bustling main bazaar on one glacially cold evening in February, she recalls bargaining for a triangular chunk of lapis, streaked with calcite clouds, from a dealer named Abdul Majid. It was the first of decades of haggling sessions in far-flung locales, from desert shops in Mali to street stalls in Oxford, always for lapis. She wears that initial prize on a silver chain still today.

cross the Khyber Pass in the Pakistani border city of Peshawar, lapis dealers showed her raw blocks by the ton, piled in warehouses, as well as finished jewelry on display in their shops. “That big piece there came from Peshawar,” she says, nodding toward an iridescent orb, perched on its own stand on a table of hammered brass. The “big piece” is as broad as a hand, its oceanic blue expanses striated with milky calcite and flecked with sparkling pyrite. It looks like a planet. She invites me to pick it up, and I instinctively strengthen my grip: It must weigh four or five kilos (9-11 lbs).

cross the Khyber Pass in the Pakistani border city of Peshawar, lapis dealers showed her raw blocks by the ton, piled in warehouses, as well as finished jewelry on display in their shops. “That big piece there came from Peshawar,” she says, nodding toward an iridescent orb, perched on its own stand on a table of hammered brass. The “big piece” is as broad as a hand, its oceanic blue expanses striated with milky calcite and flecked with sparkling pyrite. It looks like a planet. She invites me to pick it up, and I instinctively strengthen my grip: It must weigh four or five kilos (9-11 lbs).

Although I’ve never haggled for lapis like Searight, some of her infectious enthusiasm for the stone has rubbed off. My own gem hunts, however, turned out to be tamer stuff, confined mainly to excursions to Vienna’s Liechtenstein Museum and London’s Victoria & Albert.

|

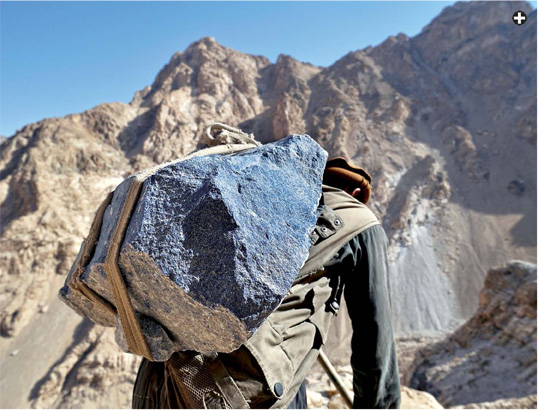

| PhILIP PoUPIn / LIghTmEDIATIon |

| A miner named Ehsan carries a 100-kilogram (220-lb) lapis stone down to a village an hour away. |

|

| PhILIP PoUPIn / LIghTmEDIATIon |

| For some 7000 years, in one of Afghanistan's most remote regions, miners have hacked and blasted lapis from mines tunneled into the vertiginous rock of Badakhshan. |

In the garden palace museum of the Liechtenstein family, surrounded by masterworks by Rubens, Rembrandt and van Dyck, stands the most expensive piece of furniture ever sold. The Badminton Cabinet fetched £19 million ($36.7 million) at auction in London in 2004. Created in the 18th century by Florentine pietra dura artisans of the Grand Ducal Workshops founded in 1588, it displays some of the most elaborate designs ever devised in lapis, amethyst quartz, red and green jasper and other semiprecious gems. The unbelievably painstaking technique involves piecing together veneer slivers only a few millimeters thick into a pattern or picture, and doing it so precisely that the joins between one piece of stone and another are invisible.

The cabinet towers four meters (12' 8") high and 2.4 meters (7' 8") wide. I marvel not only at the intricate workmanship, but also at how completely over-the-top the piece is. What sort of individual would commission such a bauble? It turns out it was ordered in 1726 by a 19-year-old English aristocrat, Henry Somerset, Duke of Beaufort and resident at Badminton House, Gloucestershire, who was in Florence for all of seven days on his European grand tour.

Contriving ornate confections with lapis and other gems had become the rage in 18th-century and early 19th-century Europe. Making my way to the Victoria & Albert Museum to view the Gilbert collection—a glittering hoard of bibelots and furniture donated in 1996 by British real-estate developer Sir Arthur Gilbert—I came across an extraordinary snuff box and a necklace, both with shell and coral patterns inlaid in lapis backdrops meant to represent the sea. Nearby stood another ebony cabinet from Florence’s Grand Ducal Workshops, dated to between 1700 and 1705: Although half the size of the Badminton Cabinet, it was every bit as finely designed and executed, with lapis ribbons that thread behind a necklace of chalcedony pearls and flowers of pink agate and blue lapis.

|

|

|

| PhILIP PoUPIn / LIghTmEDIATIon |

| Top to Bottom: Both the Afghan government and international artisanal organizations recently began efforts to improve conditions for miners in an almost entirely unregulated industry. Sorting and grading lapis in the village of Ma'dan, Hamidullah and others like him bag the stones and load them onto trucks for transport to larger wholesalers, many in Peshawar, but others also in China. |

Although pietra dura objects were also manufactured in Rome, Venice, Milan and elsewhere in Italy, Florence was the undisputed center of the craft, no doubt thanks to the Medicis’ affection for opulent decoration, and lapis lazuli was often a star attraction. As Searight points out, lapis was a spectacular status symbol and an unmistakable sign of great wealth.

Some of the most famous, superbly bombastic examples are ensconced in the Medicis’ Pitti Palace. A 16th-century urn, hewn from a single hunk of lapis, stands 40 centimeters (16") high; a more delicate, shell-shaped cup was carved by itinerant masters of the Miseroni family, who later worked for the Hapsburg court in both Prague and Madrid. The Medicis also ensured that their favored painters, like Fra Filippo Lippi and Fra Angelico, were supplied with enough lapis to make precious pigment for their art.

How, then, did such quantities of lapis arrive in Florence in the 15th to the 18th centuries? Searight speculates that most came overland from Venice and Livorno, after delivery to these ports

by ship from Constantinople and Alexandria. She cites records of Turkish prisoners chopping up blocks of lapis on the Livorno quay- side to make the chunks easier to transport the 80 kilometers (50 mi) east to Florence. “No doubt, apothecaries in Venice and else- where supplied lapis for pigments,” she explains. “But the whole question of the lapis trade to Italy and indeed to the rest of Europe needs much more research,” she adds.

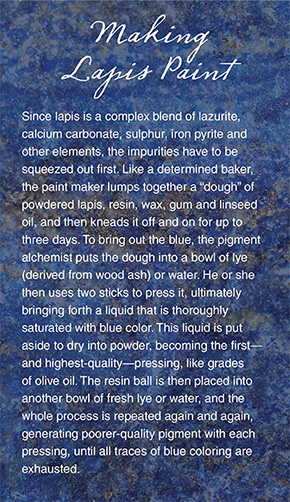

The name first used for lapis pigment is still used today for the richest blue: ultramarine, which comes from the Italian oltramarino, meaning “[from] overseas.” In 1508, artist Albrecht Dürer penned a furious letter from his home in Nuremberg complaining about the extortionate cost of ultramarine—100 florins for less half a kilo (1 lb) of paint. According to British art historian Victoria Finlay in her 2004 book, Color: A Natural History of the Palette, such paint produced from Afghan lapis today, using Renaissance techniques, would price out at roughly the same exorbitant level, equivalent to some $8000 a kilo, or $228 an ounce. The German master, like other European artists, blended lapis pigment with linseed oil or eggwhite to whip up what Finlay calls “an exotic blue mayonnaise.” But from 1828, demand for pigment made from lapis plunged nearly to zero with the discovery of synthetic ultramarine by French chemist Jean-Baptiste Guimet and his German colleague Christian Gmelin.

Nowadays, only a few die-hard icon painters and amateur experimenters like Finlay and Searight bother to pound lapis into pigment. According to both, it’s an exasperating, time-consuming task, a terrible grind that requires a great deal of rock to yield a paltry amount of paint.

One of the world’s oldest concentrations of lapis paintings is in the Kizil caves, 80 kilometers (50 mi) or so from the Silk Road trading town of Kucha in China’s Xinjiang Province. Beginning as early as the third century, upward of 5000 Buddhist monks, occupying a thousand caves in the cliffs above the Muzat River, vibrantly depicted parables, called the Jataka tales, which trace the life of the Buddha. Teacher-disciples known as bodhisattvas, dancers and winged musicians are all portrayed in brilliant lapis hues. Some 200 paintings are well preserved, but many others have been defaced. (More than two dozen murals were ripped out in the early 20th century by German archeologist Albert von Le Coq, and they now rest in Berlin’s Museum of Asian Art.)

|

|

| Journalist, scholar and lapis collector Sarah Searight's 40-year investigation of the history, art and commerce of lapis has taken her to dozens of countries—and their jeweler's markets, where she has collected both modern and neotraditional styles. |

earight recalls that the overall effect of beholding these remote grottoes is spectacular. When she first visited them in the 1990’s, neither lapis jewelry nor raw stone was available in the markets near the caves or at Kucha. But on a more recent excursion a few years ago, she says, she noticed an abundance of both lapis stones and jewelry. “It must be due to the new lapis trade into China, particularly to Hong Kong,” she says.

earight recalls that the overall effect of beholding these remote grottoes is spectacular. When she first visited them in the 1990’s, neither lapis jewelry nor raw stone was available in the markets near the caves or at Kucha. But on a more recent excursion a few years ago, she says, she noticed an abundance of both lapis stones and jewelry. “It must be due to the new lapis trade into China, particularly to Hong Kong,” she says.

Searight was amazed at reports she heard about the numbers of Chinese buyers making the arduous and risky trek to Badakhshan. From there, they truck the raw blocks overland into China or south to Karachi; other shipments go down the Indus River to Karachi, where they are loaded onto container ships bound for Hong Kong, the gem capital of the world. Although the bulk stone is cut in low-cost factories in Shenzen and further north in Wuzhou, Mohr explains, operations are moving deeper inland to where labor and materials are even cheaper. Mohr, like Mogbil and other dealers in Idar-Oberstein, has carved out a high-end niche, and he is not, at the moment, concerned about competition from China, where the focus is on cheaper lapis goods.

“In fact, it’s a positive development,” reasons Mohr. “The demand for lapis is higher because Chinese producers have kept the price low. If production were limited to Germany, the price would be too high, and demand would drop,” he points out. “Overall, the production in the Far East is making the stone more popular.”

Despite Mohr’s optimism that Idar-Oberstein’s trade will continue to thrive, outsourcing at least part of the manufacturing process to Asia remains a necessity there, too. Every week, via air freight, Mohr sends thousands of gems, including lapis, to be cut and faceted at factories in Sri Lanka, where wages are a fraction of those in Germany. Most of the large companies in Idar-Oberstein similarly outsource cutting and faceting, he says, usually to Sri Lanka, Thailand or China. “We have to do this to survive,” he acknowledges.

|

|

Top: Peter Sanders;

Above: Courtesy Sarah Searight |

| Top: Sarah Searight holds Arshad Khan's orb, which appears at the top of this article and on the cover of the print edition. Her fascination with lapis, she says, began in her early teens with a poem by Robert Browning, and a lifetime fascination with "a blue that pierce the senses." Above: Khalil Mogbil was among the Afghan jewelers who fled the Soviet occupation of the 1980's and settled in Idar-Oberstein, Germany. |

On the supply end, no one I spoke with was afraid that the Badakhshan mines would run out of lapis—or that politics would interfere unduly with trade. “Whoever is in charge of the government, they’ll keep the mines open for the revenue,” Mohr maintains.

But in Badakhshan, conditions have barely improved in generations, according to Finlay, who in 2001 hitched rides on a United Nations plane and a battered Soviet Army jeep, rode donkeys and hiked to the mines. Climbing the steep trails from the village of Sar-e-sang, where the poorly paid miners live in mud houses, to inspect some of the 23 mines, Finlay explored shafts that were dug 250 meters (800') horizontally into the mountainside. She learned that, although miners blast chunks out of the jagged blue veins with dynamite, few wore hard hats or masks. Accidents and bronchitis were chronic hazards. The nearest clinic was a bumpy, two-hour drive away in Eskazer, and it was there that Finlay met a “smiling, almost saintly man” she identifies in her books as “Dr. Khalid,” who told her he certified two or three deaths a year and treated about five miners every month who had been injured by explosives, falling rocks and tumbles off the dangerously steep trails. He also said he saw some 50 cases of bronchitis a month. “They are working without masks,” Khalid tells Finlay in her book. “Of course their lungs are damaged.”

Over the past couple of years, however, Afghanistan’s mining ministry has launched some initiatives to ensure the miners’ safety and promote the Afghan gem industry.

Despite these moves to transform Afghanistan’s wealth of lapis (as well as emeralds, rubies, tourmalines, aquamarines and other jewels) into fairer and more profitable enterprises, the industry remains rife with smuggling and corruption. Although the country exports some $50 million a year in all types of uncut stones, the vast bulk of these gems are smuggled across borders, according to mining ministry reports, thus generating little tax revenue. To a disproportionate extent, Afghanistan’s loss is Pakistan’s gain: While Pakistan’s burgeoning gem industry employs at least 40,000 people and produces $350 million in exports, Afghanistan has a mere 5000 part-time miners working seasonal jobs; fewer than 500 artisans earn a living manufacturing jewelry.

|

Afghan mining minister Wahidullah Shahrani told The Financial Times in 2011 that he plans to introduce reforms, including slashing taxation and export tariffs to reduce the incentive for smuggling, providing miners with safer explosives and granting them official leases. “They’re very keen that the government should recognize their ownership,” he explained. With the country aiming to exploit deposits of iron, copper, lithium and other largely untapped mineral resources—estimated to be worth a staggering $3 trillion—the lapis industry could become a model, though a comparatively small one, for cleaning up a troubled export business.

Selling Afghan-made lapis over the latest version of the Silk Roads, the Internet—as Turquoise Mountain and Pippa Small do on their Web sites—may be a brave boost to the industry at the source of the world’s best lapis. It is also the most recent chapter in the 7000-year-old pursuit of a stone whose color “pierces the senses,” as Searight put it: the celestial stone.

|

In addition to contributing regularly to Saudi Aramco World, Paris-based Richard Covington (richardpeacecovington@gmail.com) writes about culture, history and science for Smithsonian, The International Herald Tribune, U.S. News and World Report and The Sunday Times.

|

|

Peter Sanders (photos@petersanders.com) has photographed extensively throughout the Middle East and Islamic world for more than 30 years. He lives near London. |