testtesttest

|

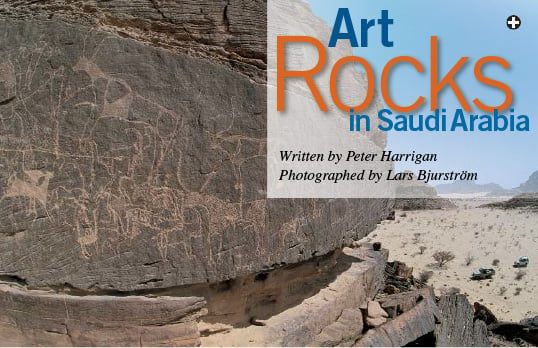

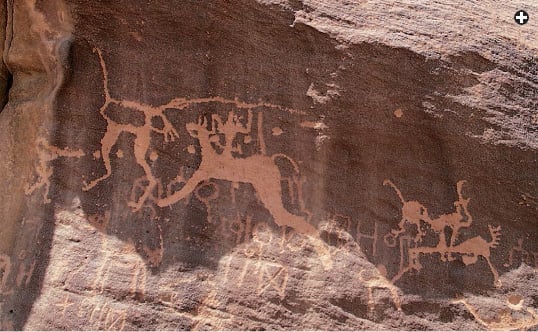

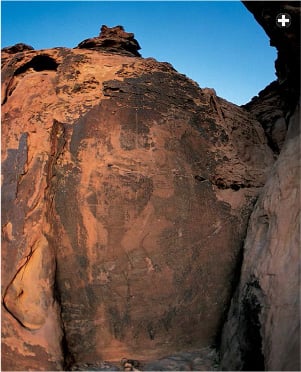

| Near Bir Hima, in Saudi Arabia’s southern Najran region, a parade of piebald long-horned cattle, ibex, ostrich and camel-riders marches above the surrounding plains. The frieze shows a variety of styles, suggesting it was carved by several artisans at widely differing times. |

“Jubbah is one of the most curious places in the world, and to my mind one of the most beautiful,” wrote Lady Anne Blunt. The granddaughter of Lord Byron had arrived in January 1879 with her husband, Wilfrid, at the oasis two-thirds of the way across the Nafud desert. En route to the city of Hail to see, and perhaps buy, some of the famous horses of Ibn Rashid, then ruler in Najd, they were among the first travelers from the West to set foot in Jubbah. Although not geologists, they recognized that the plain, more than 16 kilometers long and five kilometers wide

(10 x 3 mi)—“a great bare space fringed by an ocean of sand” and overlooked by a sandstone massif”—was the site of a former lake. Among the rocks, Wilfrid found inscriptions. They had been on the lookout for traces of ancient writing, but had “hitherto found nothing except some doubtful scratches, and a few of those simple designs one finds everywhere on the sandstone, representing camels and gazelles.”

| Petroglyphs, Pictographs and Rock Art |

| A petroglyph is inscribed into the natural surface of the rock with a chisel, pointed hammer or other tool. A pictograph is drawn or painted on the natural surface of the rock. “Rock art” is a general term for any intentional human markings on rock, including pictographs and petroglyphs, in any combination. Strictly speaking, in Saudi Arabia all known rock art is petroglyphs; however, today most professionals find the term “rock art” the most useful in their rapidly developing field. |

When it came to rock art, 19th-century westerners were interested mainly in writing: Anything else they found unworthy of attention. But attitudes have changed. Today, rock art is recognized as sophisticated, complex and esthetically interesting evidence of how early humans socialized their landscapes. Pictures carved or pecked into rock speak to us all, however faintly or incomprehensibly, across great divides of time, and appeal powerfully to our imaginations. According to Paul Bahn, a leading scholar of prehistoric art, it “gives humankind its true dimension” by showing that even from the earliest times, “human activities hold meanings other than those of a purely utilitarian kind.”

The “simple designs” that the Blunts saw can still be seen today: a veritable gallery of rock art that survives in the stark mountain area west of what is now a small modern town. The parade of images and elaborate symbols, left there by successive prehistoric nomadic and settled groups, leads up to more recent written inscriptions that lie on the horizon of history.

Nearly a century after the Blunts’ visit, scholars began to grasp the importance of these pictures. The first state-sponsored archeological and paleo-environmental surveys of Jubbah and other sites were conducted by Saudi Arabia’s Department of Antiquities in 1976 and 1977. These located and recorded thousands of images and inscriptions, and they proved that the Jubbah site did indeed lie on an ancient lake-bed stretching eastward from the sandstone mountain called Jabal Um Sanaman, “Two Camel-Hump Mountain.”

|

| The so-called “Lion of Shuwaymas,” the site’s largest petroglyph, testifies to a past climate very different from Saudi Arabia’s present one. |

And now, 35 years after the surveys, Jubbah is the centerpiece of some 2000 known rock-art sites across Saudi Arabia. Both within the country and internationally, with interest sparked by new finds and increasingly accurate dating methods, their significance is finally emerging.

Although rock art has been found in just about every nation, Saudi Arabia’s extensive heritage has remained virtually unknown. For example, the 1998 Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art does not mention Saudi Arabia, and its map of prehistoric rock-art sites shows the whole of the Arabian Peninsula as a blank.

Although rock art has been found in just about every nation, Saudi Arabia’s extensive heritage has remained virtually unknown. For example, the 1998 Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art does not mention Saudi Arabia, and its map of prehistoric rock-art sites shows the whole of the Arabian Peninsula as a blank.

This shows how much there is yet to learn, says Robert Bednarik, founder and current president of the International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (ifrao). “Saudi Arabia is one of the four richest regions in the world for rock art, along with South Africa, Australia and India. It possesses a major concentration of sites—yet, until now, this has not been realized internationally.”

ednarik paid his first visit to Saudi Arabia in late 2001, including a visit to a major new discovery in a remote area of Saudi Arabia that until now was thought to be devoid of rock art. The site, called Shuwaymas after the nearest village, “stands ready to surpass...any other rock-art site on the Arabian Peninsula,” he says.

ednarik paid his first visit to Saudi Arabia in late 2001, including a visit to a major new discovery in a remote area of Saudi Arabia that until now was thought to be devoid of rock art. The site, called Shuwaymas after the nearest village, “stands ready to surpass...any other rock-art site on the Arabian Peninsula,” he says.

|

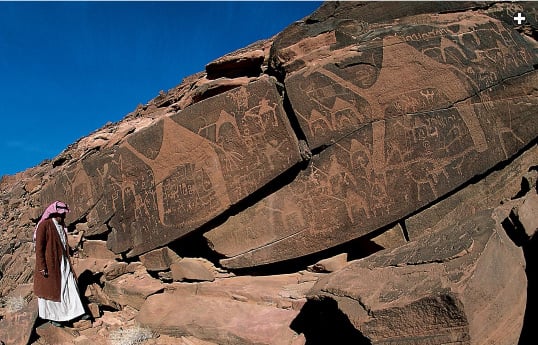

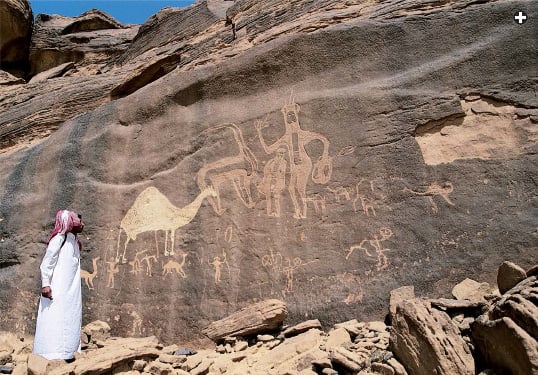

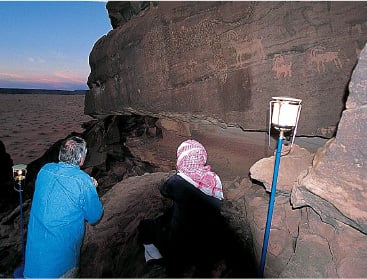

| Mamduah Ibrahim al-Rasheedi stands before a few of the scores of petroglyphs at Shuwaymas whose discovery he reported to national antiquities authorities. |

In contrast to Jubbah, Shuwaymas is surrounded by black volcanic lava, not sand, in one of the dry valley systems in the south of Hail province. Professor Saad Abdul Aziz al-Rashid, Deputy Minister for Antiquities and Museums, calls it “a unique and very important find,” and points out that it can tell us much about the early domestication of animals. “As well as rock art, there are also numerous ancient stone ‘kites,’ mounds, tails and enclosures in the area,” says al-Rashid.

|

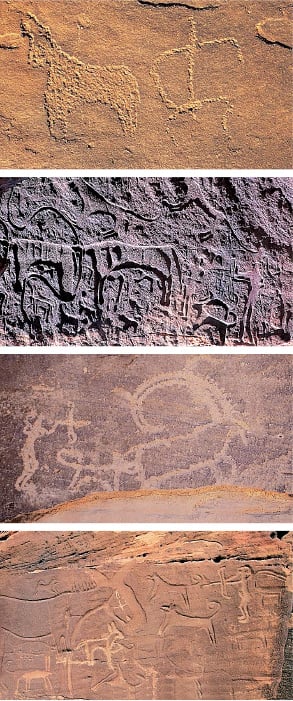

| Like those at many sites, the petroglyphs at Shuwaymas were made by pecking, chiseling or scraping the rock, or by some combination of those methods. It appears that none of the images was painted, since no traces of pigments have been found. |

The discovery came in March 2001, when a Bedouin told Mahboub Habbas al-Rasheedi, a teacher in the nearby town, about rock images he had spotted while grazing his camels. After days scouring the crumbling sides of valleys up to

65 kilometers (40 mi) distant from the school, al-Rasheedi stumbled into a proliferation of rock art tableaux, including an unusually detailed carving nearly two meters (6') from head to tail that has been dubbed “the lion of Shuwaymas.”

Further explorations by al-Rasheedi and his brother Saad yielded fresh discoveries incised and pecked into the rock: images of cheetah, hyenas, dogs, long- and short-horned cattle, oryx, ibex, horses, mules, camels and ostrich; human figures; geometric shapes, serpentine squiggles, inscrutable symbols, carved-out footprints and, perhaps, hoofprints.

“We kept coming back to reflect on the place, on what these pictures mean and the stories they tell. Somehow we are connected to them,” says Mahboub al-Rasheedi. The brothers took their local school superintendent, Mamduah Ibrahim al-Rasheedi, to the site. “As soon as I returned home,” says Mamduah, “I clambered up a nearby hill where my cell phone can work, and I called the provincial director of antiquities in Hail to report that we had found something.”

“The Shuwaymas area is densely peppered with rock art, and it likely had a very heavy and significant concentration of Neolithic people,” says Bednarik, whose more than 650 publications in more than 50 professional journals make him one of the most extensively published archeological authors. “Clearly a great deal of labor has been invested here. It reminds me of Egyptian material and also Saharan rock art. There are lots of questions here that, if answered, could well change opinions and attitudes. This is the beginning of a major research opportunity.”

ubbah, 35 years ago, was just as little known as Shuwaymas is now. But now we are aware that Arabia has not always been desert, and indeed that the region has undergone considerable climatic changes. The sequence

of strata in the lakebed at Jubbah is similar to those in locations in the

Rub’ al-Khali (the Empty Quarter) and the al-Jafr Basin in Jordan, as well as long-dry African lake basins in the Sahara. All of this region underwent successive moist and arid periods, and during the Neolithic Wet Phase (9000–6000 years ago), savanna grasslands supported cattle.

ubbah, 35 years ago, was just as little known as Shuwaymas is now. But now we are aware that Arabia has not always been desert, and indeed that the region has undergone considerable climatic changes. The sequence

of strata in the lakebed at Jubbah is similar to those in locations in the

Rub’ al-Khali (the Empty Quarter) and the al-Jafr Basin in Jordan, as well as long-dry African lake basins in the Sahara. All of this region underwent successive moist and arid periods, and during the Neolithic Wet Phase (9000–6000 years ago), savanna grasslands supported cattle.

Archeologists have found evidence of four major periods of settlement at Jubbah stretching back through the Middle Paleolithic period, 80,000 to 25,000 years ago. They also found Neolithic sites and evidence of early trade: finely retouched arrowheads, blades and awls manufactured

from stone that had been carried in from sources up to 145 kilometers (90 mi) away.

The panoply of rock art around Jubbah’s Jabal Um Sanaman covers some 39 square kilometers (15 sq mi), and it presents a rich, often perplexing gallery, including panels depicting early domesticated dogs and long-horned cattle, and others that suggest a transition from hunter-gatherer to agricultural communities. The abundant images of camels raise the intriguing possibility that the camel was first domesticated in northern Arabia, not southern, as is usually believed. Among the hundreds of thousands of camel figures carved in rocks throughout the Arabian Peninsula, the ones at Jubbah are believed to be the oldest: At approximately 4000 years old, they date back to the beginning of the Bronze Age.

|

Rock art, unlike the archeology or epigraphy of more recent eras, offers virtually no pottery shards, burial places, monuments or even legends to help determine how old it is. Specialists must extract that information from the rocks themselves.

Much of Saudi Arabia’s rock art is on sandstone. Over long stretches of time, the surface of the stone is covered with a wind-smoothed accretion of manganese and iron salts, a patina sometimes called “desert varnish” that can help determine the relative chronology of rock art in places where successive cultures have cut images onto the same rock panel: The darker images are older than the lighter ones.

Another method relies on linking the art with environmental sequences, the “paleo-ecological record.” Here, findings are tied to known climatic periods when the creatures depicted in the rock art might have lived there: Hippos, for example, need lakes and rivers; when was the climate wet enough for lakes and rivers to exist? This method, however, is rather imprecise and not always unambiguous. For example, depictions of cattle might have been made in any of several periods, over many millennia, when the climate was wet enough to grow enough grass to support large ruminants.

Occasionally, there are links to the archeological record—to shards or bones or tools whose age can be more or less precisely determined. This linkage requires careful excavation, however, and it is a time- and resource-consuming activity that often produces scant results.

In his study of the photographs, tracings and sketches from the Philby-Ryckmans-Lippen expedition, Emmanuel Anati proposed a chronology of Arabian rock art based on visual style, rather as art historians do with paintings today. He divided the art into periods ranging from the Islamic back through the literate, pastoral and hunting periods, back to early hunters more than 8000 years ago. He then distinguished 35 distinct “styles,” defining traits of human figures such as “oval-headed people” and “long-haired people,” and placed them into his periods. “Each style has its own figurative repertoire, its own approach to scenes and compositions,” he argued, adding that “in many cases, stylistic differences may represent the presence of different cultural groups.”

Majeed Khan considers Anati’s classifications and dating of dubious value. “We have no idea on what his dating is based. Neither does he make any attempt to correlate his dating with the archeology of the region.”

Robert Bednarik has carved out his international

reputation with a more precise approach. During his own research in Saudi Arabia, he used two methods. First, he took samples of the sandstone patina for radiocarbon analysis, in case the mineral accretion contained trapped organic matter such as wind-blown micro-organisms and pollen, or algae formed in wetter climatic periods. “The difficulty,” says Bednarik, “is to relate the result to the age of the rock art. Obviously it becomes much easier if the art was painted with organic pigments, which often survive in cave art, but there are no known examples of that here as yet.”

The second dating technique involves tracking micro-erosion, and it was this that Bednarik employed for the first time anywhere in the Middle East at both Shuwaymas and Jubbah. When the artist scours and pecks the rock using stone and antler tools, Bednarik explains, sharp-edged rock particles such as quartz are freshly exposed to the elements and to erosion. “Ideally we need large grain sizes for this to work,” he says, so sandstone is not the best material. Nonetheless, Bednarik did find “some particles with decent grain-size.” Then, using optical instruments, he calculated a curve that represents the degree of erosion of the particles over time. To do this, however, requires a comparable geological sample exposed from a nearby site that displays other work, such as inscriptions, that can be reliably assigned an age on epigraphic or other grounds. Variables in the process include climatic changes and other micro-environmental factors such as wind exposure.

The micro-erosion method has also been used recently at other sites to date finds of tools used in rock-art production. Since petroglyph hammers are frequently made of quartz, their fractured edges—or the edges of tiny spalls detached during their use—“certainly lend themselves to micro-erosion analysis,” says Bednarik, if the tools have remained on the surface, exposed to weathering. Results of his findings in Saudi Arabia will be published in Atlal: The Journal of Saudi Arabian Archaeology later this year.

Most specialists accept that all dating techniques have both merits and flaws. “The future of prehistoric-art studies,” says Paul Bahn, “depends heavily on the judicious balancing of the one [technique] with the other, while avoiding a blind faith in the infallibility of any.” |

Among the most recent markings in the chronology of Jubbah’s early civilizations are 3000-year-old inscriptions in Thamudic, the oldest known script of the Arabian Peninsula. Majeed Khan, the leading authority on the rock art of Arabia and the Middle East, is currently an advisor to the national Antiquities Department; he has spent 27 years studying rock art and inscriptions. The Thamudic script, he says, “evolved independently within the Peninsula from an earlier rock-art system of communication, an embryonic form of writing employing elaborate signs and symbols as ideograms.”

|

| An ostrich is the prey for a lance-wielding, horse-borne rider. |

Along with Khan, archeologist Juris Zarins worked on

the early surveys in the mid-1970’s, before joining the faculty of Southwest Missouri State University. Over the past two decades, he has taken many smsu students to Saudi Arabia, and he was chief archeologist of the 1992 Transarabia Expedition, which made the headline-grabbing discovery

of what they believed was the ancient city of Ubar.

“Pound for pound and piece for piece, in terms of rock art concentration and importance, Jubbah is the number-one or number-two site in the whole of the Middle East,” Zarins says. “It rivals anything in North Africa. With the art going back at least to the Pottery Neolithic period 7000 to 9000 years ago, and with paleo-environment and geology showing traces of human activity extending into the Middle Paleolithic period, it’s a treasure trove for answering questions about the Middle East.”

If so, then why has Saudi Arabia so long remained a blank spot on the international rock-art map? One reason, contends Zarins, has to do with an ancient bias: “Throughout the world, scholarship has always slighted deserts. Even the ancients despised the desert people. This has carried over into the modern world, since history is written by settled, civilized peoples.”

What makes the oversight more curious still is that there has been activity between the time of the Blunts’ visit and the modern Saudi studies. In 1972, a four-volume work, Rock-Art in Central Arabia, was published by Emmanuel Anati. Although he never visited the country, he worked from a huge corpus of photographs, tracings and sketches acquired from the explorer, mapmaker and writer on Arabia Harry St. John Philby. In the winter of 1952, Philby had set off on a three-month field survey of rock art and inscriptions in the south of the country. Accompanying him were a renowned Belgian scholar of Semitic studies, Monseigneur Gonzague Ryckmans, pre-Islamic historian Jacques Ryckmans and a photographer of rock art and epigraphy, Count Philippe Lippens. The expedition returned to Riyadh with records of 13,000 previously unknown petroglyphs. “Sad to say,” wrote Elizabeth Monroe, Philby’s biographer, in 1973, “only a fraction of this major addition to the world’s knowledge of Arabia has so far been published.” (The originals are today at St. Antony’s College, Oxford.) So rich was one of the sites west of the ancient wells of Bir Hima that one of the expedition members was able to copy 250 images without moving from his seat.

ook carefully at the black rock,” says Naif al-Ateek, the curator of the rock-art site at Jubbah and a descendant of the town amir who welcomed the Blunts. “If you concentrate, you’ll see a faint carving lying behind the clear and lighter top one.” Even with such a lead—for without it only the superficial images would register—intently staring at the blackened rock surface is an exercise akin to picking out a modern three-dimensional picture that appears buried within an inscrutable, computer-generated pattern. Yet al-Ateek is right: If one adjusts one’s eye, focusing and refocusing slowly, another image appears in the background, a work executed perhaps millennia before the more apparent images.

ook carefully at the black rock,” says Naif al-Ateek, the curator of the rock-art site at Jubbah and a descendant of the town amir who welcomed the Blunts. “If you concentrate, you’ll see a faint carving lying behind the clear and lighter top one.” Even with such a lead—for without it only the superficial images would register—intently staring at the blackened rock surface is an exercise akin to picking out a modern three-dimensional picture that appears buried within an inscrutable, computer-generated pattern. Yet al-Ateek is right: If one adjusts one’s eye, focusing and refocusing slowly, another image appears in the background, a work executed perhaps millennia before the more apparent images.

|

| Above the plain near Bir Hima, the camel on this panel is a recent addition to an otherwise curious frieze: An oryx faces one of the most naturalistic human figures found in Saudi rock art; he wields a spear and holds what may be a shield, wears feathered headgear and shows what may be tattoos on his abdomen. A smaller figure—a child?—appears under his arm. |

|

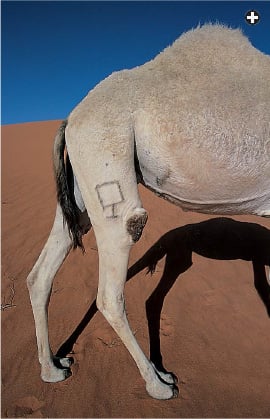

| Marks, known as wasum, like this one branded onto a camel’s leg, are tribal symbols of ownership. Scholars are finding more and more links between rock-art designs and the nearly 4000 known wasum. |

“The darker ones are the oldest,” he explains, showing a life-sized figure, depicted with a characteristic oval head, holding a curved, boomerang-like throwing stick and followed by a short-horned bovine. “Now let me show you our prize figure, an ancient ruler.” Finely incised in the dark patina of desert varnish is a life-sized male human figure with a crown-like headdress. Nearby is the curved horn of an ibex reaching and arching to its back, its face complete with a small beard.

Later, after a day spent scrambling over rock surfaces,

al-Ateek serves coffee in the same smoke-blackened parlor that the Blunts sat in. He has built up a small museum that includes several rock-art fragments found in the sands and brought in by Bedouin over the years.

“We are proud of our mountain and the heritage it contains,” says Bandar al-Amar, who has opened Jubbah’s own Internet café, runs computer courses and created an Arabic-language website for the town (jubbah.netfirms.com). “Twenty years ago our parents pressed to have a tarred road brought across the dunes to Jubbah from Hail,” he says. “The authorities suggested that we move to Hail and resettle in the modern town. The answer was ‘Okay, so long as you move our mountain with us.’ This here is all part of our deep past, even though its history is difficult to understand.”

Just three years ago, a rock with one of Arabia’s most intriguing petroglyphs was moved: A helicopter hoisted it from its site 160 kilometers (100 mi)  north of Najran and lowered it onto a flatbed trailer, and it was later craned onto the marble floor of Riyadh’s National Museum. The rough, pyramid-shaped sandstone rock, 1.3 meters (4') tall, shows arms and hands waving on one side and another hand, apparently with a broken arm, on the other. The motif is ubiquitous in rock art throughout the world.

north of Najran and lowered it onto a flatbed trailer, and it was later craned onto the marble floor of Riyadh’s National Museum. The rough, pyramid-shaped sandstone rock, 1.3 meters (4') tall, shows arms and hands waving on one side and another hand, apparently with a broken arm, on the other. The motif is ubiquitous in rock art throughout the world.

The Department of Antiquities and Museums is also quartered at the National Museum. In his office, surrounded by journals, surveys, publications and rock-art conference proceedings, Majeed Khan explains why he prefers not to interpret the meaning of the waving hands, let alone any other rock art images.

“The biggest challenge with rock art is chronology and dating. Once we tried to interpret the art, but with our modern minds interpretation is entirely hypothetical. So now we concentrate on dating, chronology and the technical aspects.” He adds one exception, unique to Saudi Arabia: Tribal markings called wasum are still used today by Bedouin to mark territorial and animal possessions. They provide a modern link with much older rock art. Khan’s Wasum: The Tribal Symbols of Saudi Arabia was published by the Ministry of Education in 2000.

|

Faced with thousands of sites to survey, research and preserve, Saad Abdul Aziz al-Rashid, Deputy Minister for Antiquities and Museums, has about him an air of excitement modified by a touch of frustration. His staff of 320, he says, is being stretched thin by the fast-growing field.

“It is difficult to keep up with it all. We need people to protect the sites, resources for preservation work, experts to survey, research and interpret. We also need to educate the public, since there is abuse of sites, with defacing and damage to rock art. All the while there are new sites discovered, which further stretch our professional staff and our resources.”

The biggest threat to rock art is, not surprisingly, from modern humans. Many of the human and animal figures in better-known, unprotected areas are pockmarked by bullets; local Bedouin complain that hunters have used the images for target practice. Marginally more respectably, if only because it is in keeping with ancient tradition, shepherds of recent centuries have used metal instruments to carve their new images alongside or even on top of ancient panels. Passing travelers often engage in “pot-picking,” or the illegal removal of artifacts from areas of rock art—the very lithic remains that might yet help date the art. So it is that irreversible damage often results more from ignorance than malice.

Regardless of intent, however, Saudi law now protects designated sites unequivocally: Disturbing a rock-art site is illegal, punishable by a jail sentences and stiff fines. The laws are often enforced by local guards.

Still, with more interest and respect for the heritage of rock art, the largest problem faced by rock-art site managers around the world is unintentional damage caused by the sheer volume of otherwise well-intentioned visitors. Even touching rock art can accelerate its deterioration, and repeated touching by many hands can have a rapid cumulative effect.

Moving rocks to facilitate visitor access—for sites are often located up steep valleys—can put the integrity of a site at risk. Local development associated with farming, new settlements and road construction can also lead to losses. Natural deterioration also plays its constant role, with erosion caused by extreme temperatures, blowing sand and dust, occasional earth tremors and rainwater all taking their inexorable toll. On the softer sandstone surfaces, this erosion can range up to 50 millimeters (2") every millennium; on granite the surface retreat is often as little as .05 millimeter (.002") in the same period.

“With tourism now opening up in Saudi Arabia, we have the added challenge of making the sites accessible to the public, providing information, and guarding against degradation and abuse,” says al-Rashid. |

In the museum gallery, Khan demonstrates further the

pitfalls of interpretation. “You might say this is a territorial marker,” he says as he and a group of schoolchildren ponder the rock with the waving hands. “That child might say it’s a keep-out sign, for the broken arm on the rear face shows the consequence of intrusion. I might suggest that it reveals supplication to some deity. You could speculate these incised images from handprints daubed onto the rock are mere doodles by a person with time—and paint—on his hands: Art for art’s sake!

|

| PETER HARRIGAN |

| One of the most unusual petroglyphs at Jubbah is this horse-drawn chariot, shown in an unusual vertical perspective. It is probably 2000 to 2500 years old. Jubbah’s greatest value is that it contains petroglyphs from most major phases of habitation: Middle Paleolithic, Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Thamudic and Arabic. |

“With such a diversity of ideas, how can we interpret the meaning of people’s thoughts thousands of years ago?” asks Khan. “One thing is clear to me though: These images were symbolic, communicating meaning which the artist and the ancient people of the time could understand.”

Khan’s words echo those of Paul Bahn. In most rock art, argues Bahn, “individual artistic inspiration was related to some more widespread system of thought and had messages to convey: signatures, ownership, warnings, exhortations, demarcations, commemorations, narratives, myths and metaphors.”

|

|

| Locally called “The King,” this large, heavily eroded human figure, seen in profile, has muscular arms, fingers on each hand, a blank face, a short skirt and a headdress that may be made of ostrich feathers. Experts believe it probably dates from the Neolithic period, making it between 6000 and 9000 years old. |

Among the younger Saudi scholars devoted to rock art is Abdulraheem Hobrom, one of the first to undertake postgraduate studies in the subject at Riyadh’s King Sa‘ud University. He sees a wide-open field, and attitudes changing in ways that will favor further study. “Islam encourages us to explore and discover the world. People are recognizing the significance of the shared legacy and heritage of rock art. Our ancestors created these works, and we need to understand them,” he says.

More publications, increased survey activities and a documentary film in progress, intended for broadcast in Europe, all show the growing interest in Saudi rock art, says Daifallah al-Talhi, director general of the Antiquities Research and Survey Center. “We display rock art in our provincial museums, our mobile exhibition on education in history includes it and we will soon launch a website for the National Museum which will feature petroglyphs,” he says. Provincial representatives of the Ministry of Education discuss the country’s rock-art heritage in presentations to schools throughout Saudi Arabia’s 13 provinces.

This heightened interest, naturally, is leading to another prospect—more discoveries. Saad al-Rashid is a busy man these days, one who often returns to his office at the National Museum in the evenings to work past midnight. He talks of prospects for new studies to address the questions that multiply with the discoveries. “To what extent are the wasum of today inherited by tribes, and were there tribes that no longer exist? When were the animals domesticated in Arabia? There are so many facets to examine—and of course always the scientific challenge of accurate absolute dating.”

His enthusiasm is echoed by Bednarik. “Saudi Arabia is taking on a pioneer role. This could lead to better things in terms of rock-art studies in other Arab countries, and opting for a scientific approach rather than one of interpretation makes eminent sense. It’s also appropriate, as the Arabs were at the forefront of scientific tradition and innovation in the past.”

n the middle of the broad, flat, sandy valley of the Shuwaymas site, a small campfire flickers under a canopy of stars in a crystalline sky. Sharing its warmth, sipping coffee and tea, are two Bedouin who live in tents a few kilometers away and who are now officially charged with guarding the site. Also sitting at the fire are Mamduah Ibrahim al-Rasheedi, the school superintendant who called in the find, his teacher colleagues and Saad Rowaisan, the visiting provincial director of antiquities from Hail. They muse over how this once-populated site has been virtually unknown for nearly the full duration of recorded history, and they speculate what their find will bring to this remote area: survey teams, archeologists, students, international specialists, film crews and curious visitors with four-wheel drives and gps navigation units. Al-Rasheedi already plans a visit for his schoolchildren. There will, of course, be more.

n the middle of the broad, flat, sandy valley of the Shuwaymas site, a small campfire flickers under a canopy of stars in a crystalline sky. Sharing its warmth, sipping coffee and tea, are two Bedouin who live in tents a few kilometers away and who are now officially charged with guarding the site. Also sitting at the fire are Mamduah Ibrahim al-Rasheedi, the school superintendant who called in the find, his teacher colleagues and Saad Rowaisan, the visiting provincial director of antiquities from Hail. They muse over how this once-populated site has been virtually unknown for nearly the full duration of recorded history, and they speculate what their find will bring to this remote area: survey teams, archeologists, students, international specialists, film crews and curious visitors with four-wheel drives and gps navigation units. Al-Rasheedi already plans a visit for his schoolchildren. There will, of course, be more.

As the coffee-maker tends the embers, talk turns to the people who left their mark on the rocks. “Our children will ask, ‘Who were the people who left all this? How did they live, how did they cut the pictures and symbols in the stone?’” says Ruwaisan. “‘What were the dogs used for, and why did the cows, lions and cheetahs disappear?’”

Later, after a simple meal, the conversation dies, marking the time for reflective silence interspersed with poetry recitations. The small cloaked gathering draws closer to the fire and listens to verses from an eighth-century qasidah by Jarir ibn ‘Atiya that opens in the traditional way, with an image of a deserted campsite. Like the art flickering faintly on the rocks, it seems to speak from a distant past.

|

| PETER HARRIGAN |

O, how strange are the deserted campsites and their long-gone inhabitants!

And how strangely time changes all!

The camel of youth walks slowly now;

Its once quick pace is gone; it is bored with traveling.

|

Peter Harrigan (harrigan@zajil.net) works with Saudi Arabian Airlines in Jiddah, where he is also a contributing editor and columnist for Diwaniya, the weekly cultural supplement of the Saudi Gazette. He has enjoyed close encounters with rock art in numerous journeys in the Arabian Peninsula over the past two decades. |

|

Lars Bjurström (larsbjurstrom@hotmail.com) has lived for four years in Riyadh, where he practices dentistry and pursues his love of wildlife and exploration photography. “The difficulty with photographing petroglyphs is to make them stand out,” he says. “To get the right light meant I had to get to the right petroglyph at the right time of day, and that meant getting up with the sun and chasing it around the sites. Getting to their locations is hard enough, so the fact of their creation is all the more astounding.” |