For students:

We hope this two-page guide will help sharpen your reading skills and deepen your understanding of this issue’s articles.

For teachers:

We encourage reproduction and adaptation of these ideas, freely and without further permission from Saudi Aramco World, by teachers at any level, whether working in a classroom or through home study.

— THE EDITORS

Activities

This special issue of Saudi Aramco World accompanies the museum exhibition “Roads of Arabia” in its North American tour. The five articles in the magazine—including one that reviews the exhibition—all address what’s being learned about the history of Saudi Arabia. In addition, all five articles in one way or another all speak to connections—connections between the Arabian peninsula and other parts of the world, and connections that we, today, make between ancient artifacts and the civilizations that created them. Forge ahead and explore how the theme of networks unites the articles.

Networks

What comes to mind when you hear the word network? As a class, brainstorm about it while a class member writes your ideas on chart paper or the board. Remember to think about network as both a noun (a thing) and a verb (an action). When you’re done, put a star next to the items on the list that are related to computers.

Look up a definition of the word network, and add the definition to your list. Now imagine 100 years ago. What existed 100 years ago that you might call a network? What about 900 or 9000 years ago? How have human groups been connected to each other over the past 9000 years? For what purposes? And what evidence do people have today that offers clues to those connections? That’s what you’ll be looking at as you work on the activities in this Classroom Guide.

Getting Oriented in Time and Space

It’s quite a task to think about human networks over a period of 9000 years! So let’s get as clear as possible about the timing. As a class, make a timeline—a big timeline that might need to stretch from one side of the room to the other! Start at the left at 9000 bce and mark time in 1000-year increments until you get to 2000 ce, a mere 12 years ago. As you read each article, put the key events and objects onto the timeline. That should help you piece together a narrative, or story, about human networks over time.

It’s quite a task to think about human networks over a period of 9000 years! So let’s get as clear as possible about the timing. As a class, make a timeline—a big timeline that might need to stretch from one side of the room to the other! Start at the left at 9000 bce and mark time in 1000-year increments until you get to 2000 ce, a mere 12 years ago. As you read each article, put the key events and objects onto the timeline. That should help you piece together a narrative, or story, about human networks over time.

Networks take place in space as well as in time, of course, so you’re also going to want to understand where the networks you’ll be reading about existed. A place to start is with the map of the Arabian Peninsula that accompanies “Roads of Arabia.” (You can find a bigger version of it online at www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/201102/popup.htm?img=images/roads/00-CarteEN_lg.jpg.) As you read the articles, locate on the map the places where people lived and events happened. You might also get a map that shows a larger area so that you can be sure you understand where Arabia fit (and fits) into the world around it.

Beginning in the Middle

Start with “Roads of Arabia.” As you’ll discover, the networks it describes are not the earliest ones (chronologically) that you’ll be reading about. Nonetheless, let’s start with them for two reasons. First, the connection to the theme networks is the clearest in “Roads”. And second, “Roads” tells about the exhibition around which this special issue of Saudi Aramco World has been developed.

According to the article (and the exhibition), “the Arabian Peninsula [was] not on the periphery of the ancient world, but squarely within a far-reaching network of trade and pilgrimage routes linking India and China to the Mediterranean and Egypt, Yemen and East Africa.” That’s the thesis of the article—the main point that the article will make and support. Write it on the board or on chart paper so that you and your classmates can keep it mind. As you read, pause and ask yourself how each segment of the article supports the thesis, and make notes so that you stay focused on the significance of various bits of information you’ll be reading.

That said, start with the map on page 4. With a group, look at the key in the bottom right corner. Start with “Commercial Roads of the Bronze Age.” Put it on your timeline. (If you don’t know when the Bronze Age was, look it up.) Look at the roads from that

era. Trace them with your finger. With your group, discuss what you see. Here are a few questions to get you started: Where are the roads? Are they clustered in one area? Do they cross land and/or water? You know from the key that they’re commercial roads—that is, they’re trade routes. What do you think might have been traded along them? Make an educated guess based on what you know about the areas that the roads cross. Hold onto your guesses; you’ll have a chance soon to see if they’re accurate.

First, though, return to the map, this time looking at the Incense Roads. Add it to your timeline. (Again, if you don’t know when Antiquity was, look it up.) With your group, study the Incense Roads. Ask yourselves the

same questions you asked about the Bronze Age roads, and once again, make an educated guess about who and what traveled along those roads. Follow the same procedure for the last set of roads on the map: Pilgrimage Roads to Makkah.

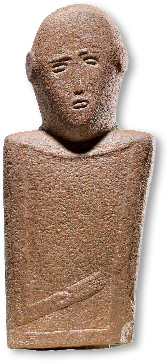

Now, at last, you’re ready to read “Roads of Arabia”! Read it in segments defined by the three time periods. After you and your group members have read a section, discuss what you’ve read. For example, in the first section, about the Bronze Age, you might talk about the “suffering man,” the statue on page 7. What influences are evident in the suffering man? What do these influences suggest about life on the Arabian Peninsula during the Bronze Age? Remember to check back in with the thesis statement and connect each section to it. When you’re done, go back to your predictions about who was trading what during each time period. Were you right? If so, congratulations! What additional understanding do you have now that you didn’t have before? If you weren’t right, what have you learned, and what do you understand now that you didn’t before? Write answers in your notebook.

“Journeys of Faith, Roads of Civilization,” like “Roads of Arabia,” looks at routes that connected the Arabian Peninsula to other parts of the world. These routes, like those discussed in the third part of “Roads,” had primarily to do with religious networks, although the religious paths frequently became commerce networks as well. Read “Journeys of Faith,” adding it to your timeline and looking for overlap between the routes it discusses and those mapped out in “Roads.” Find the thesis of “Journeys,” and write it next to the thesis of “Roads.” As you read, see how the different parts of the article connect to the thesis. In addition, think about how this article connects to the article you already read and analyzed. Discuss with your group: What conclusions can you draw about life on the Arabian Peninsula at different times? Have groups share their answers.

Going Backward to the Beginning

Two of the other articles in the magazine are a little bit different from the two you just read. The first ones focused on roads that connected people in different places. The next two articles focus on artifacts that have been discovered in Saudi Arabia. (The fifth, “Desktop Archeology,” is about one way of locating possible sites of discovery.) All the artifacts predate the roads you’ve studied, so you see now why your timeline starts so far in the past! And all of them offer clues about how people may have been connected long before the Bronze Age. The artifacts also challenge those of us living today to make connections. The connections we need to make are between the artifacts and the lives of the people who created them. In a sense, our work as detectives has us “read” these artifacts as clues that we can use to understand the past.

Read “Art Rocks in Saudi Arabia” and “Discovery at al-Magar.” Locate the time periods in which the artifacts described in the articles were created and mark them on your timeline. Highlight the parts of the article that describe the images that appear on the rocks in “Art Rocks” and the objects found at al-Magar. Then, with your group, see what connections you can make. What can you tell about the people who created the petroglyphs and the objects? What do the findings suggest that those people did? What can you tell about their ways of life? What can you tell about the climate in which they lived? On the other hand, scholars warn that there are plenty of things we can’t tell from looking at artifacts. What are some of those things? Why are scholars so cautious about interpreting what they find?

Now step into the present. (No need to add it to your timeline!) In a few thousand years, Earth’s residents may want to find out about us. What evidence might they find that would suggest that we’re connected to each other? With your group, generate a list. What kinds of evidence will be similar to the evidence you read about in “Roads of Arabia?” What kinds of evidence will be different? Then think about the objects found at al-Magar and at Jubbah. What objects might you find in a home or museum in Saudi Arabia today that you might also find in a home or museum in the United States? What does that tell you about networks today? What about the networks you can’t see—computer networks? What evidence shows that we’re “networked” electronically? Once your group has generated a list, imagine you are living 1000 years from now. Complete one of the following activities. Either work on your own to write an article about connections among people in the early 3000’s; or, with your group, develop a museum exhibit similar to “Roads of Arabia” that shows what you’ve found. Share your work with the class.

| Julie Weiss

(julie.w1@comcast.net)

is an education consultant based in Eliot, Maine. She holds a Ph.D. in American studies. Her company, Unlimited Horizons,

develops social studies, media literacy, and English as a Second Language curricula, and produces textbook materials.

|