|

| The face of vocalist and drummer Mohammed Zaid reflects the poignancy of sawt al-khaleej during a performance of the Ensemble Muhammad bin Faris in Muharraq, Bahrain. |

If you climb into a taxi in Doha, capital of Qatar, and Arab music is on the driver’s radio, the station may well be 99.0, Sawt al-Khaleej, one of the most popular and powerful radio and digital streaming broadcast networks in the region. Based in Doha, its name translates to “Voice of the Gulf”—a fitting name for a network that seeks to appeal to a broad, Arabic-speaking audience with pan-Arab popular music up and down the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, from Kuwait to Oman.

But if you ask someone who knows the music of the eastern Arabian Peninsula about this name, you might get a puzzled response: “Which sawt al-khaleej do you mean?” Today, the influence of the 12-year-old radio network, both on the dial and at www.skr.fm, is so pervasive that for many, the words have become synonymous with Arab pop. Yet it has an older and more local meaning, one that began at sea and was popularized on land, one still played throughout the region, with local styles, though one has to search a bit to hear it: It’s a genre devotees refer to simply as “sawt”—as if to imply, “the real sawt.”

|

| Beats by a tabl bahri (sea drum) player, will invite audience participation through rhythmic hand-clapping. |

This “real sawt” (pr. saowt) appeared in the late 19th century. It has a number of founding fathers, but the earliest and best known was a Kuwaiti named Abdallah al-Faraj, who died in 1903. His successors went on to develop the style at a time when commercial recording had just reached the Gulf region, and their work can still be heard today through the muffled and scratchy recordings on 78-rpm discs first made in the 1920s. Sawt is thus a 20th-century form of popular music, one spread as much by recordings as by teaching and performance.

Not only is sawt the Gulf Arabs’ distinctive contribution to Arab music—able to take a place alongside traditions of the Levant and the Maghreb—it is also one that can appeal easily to western musical ears. Indeed, sawt is sometimes called “the blues of Arabia,” for these two traditions have much in common.

|

| This antique ‘ud, on display at the Muhammad bin Faris Music Hall, once resonated with many a sawt song. |

At its simplest, sawt is led by a singer who also plays the ‘ud, the unfretted, six-string Arab lute, and he is accompanied by at least one handheld drum, called a mirwas. After that, it’s a social music: A performance of sawt involves audience participation. Members don’t just listen; they accompany the singing and playing with intricate, powerful, rhythmic hand-clapping. Even to use the word “audience” can be misleading because in sawt, there is little distinction between audience and performer.

The singer leads the song, but everybody present takes part, clapping, singing a chorus, calling out whoops of appreciation and even dancing. Sawt songs themselves have the flavor of American blues, conveying tales and evoking feelings of hardship, nostalgia, lost loves, homesickness and appeals to God for deliverance from sufferings. Even without understanding the lyrics, it is easy for non-Arabic listeners to recognize that this is powerfully emotive music, and anyone can relate to a strong rhythm.

Sawt connects Gulf Arab listeners to an earlier age, to when most people made hardscrabble livings as fishermen, pearl divers and maritime traders, before the Gulf’s economy was transformed by oil, when—as one sawt song puts it—“the gates of heaven were opened.” It differs from the simpler and more austere music of the Arabian interior, which in general eschews stringed instruments in favor of drumming, singing and chanting.

|

| A portrait of Muhammad bin Faris gazes out into the concert hall that carries his name in Muharraq. Born into Bahrain’s ruling family in the late 19th century, bin Faris followed his mentor to Bombay, where he developed his own form of sawt. |

Today, there are two ways to hear sawt: in private or in public. Purists often say that the private setting—a gathering of friends in a home, or in a clubhouse called a dar—is the original and best context, but it is traditionally an all-male occasion. In such a domestic setting, an evening of sawt takes place in the majlis, the sitting room, where members of the group sit around the room on cushions along the walls. Refreshments are served, people look at their mobile phones, and there may be a television playing in the background, although nobody pays attention to it.

A musical evening like this often lasts well into the night. A song begins when the singer feels like singing; someone calls out for people to pay attention, and the hubbub of talk gradually subsides as the song starts. Typically, everyone knows the songs being performed: They are part of the sawt tradition.

|

|

| At sawt performances, listeners take part, dancing and joining in syncopated clapping, blurring distinctions between performers and audience. |

This means that the drummers know what rhythms to play, and everyone else knows the intricate patterns of syncopated clapping that each song requires. Sawt clapping is not at all like applauding at the theater: For sawt, the palms are held flat and struck together hard, producing a sharp, precise percussive sound.

A sawt song begins with an instrumental prelude followed by a short sung phrase that is repeated. This leads to the lyrical heart of the song, usually in classical Arabic and often in lines of poetry called qasidas. The lyrics express some predicament of the heart in lofty, poetic language. “[T]he bough of the tree turned to gold when my beloved touched it, and bends low in her absence” is one example, from “Ma Li Ghusn al-Dhahab” (“What’s the Matter with the Golden Branch”), first recorded in 1932 in Basra, Iraq, by Muhammad bin Faris of Bahrain on the label His Master’s Voice. And then there will be a tawshihah, or chorus, in which everyone takes part.

In recent years, under the auspices of the folklore or cultural-heritage departments in Gulf countries, sawt concerts have been held also in public performance spaces in which admission is open to everyone. In Bahrain, for example, shows are held on most Thursday nights in the auditorium of the Shaikh Ebrahim bin Mohammed Al Khalifa Center for Culture and Research, a heritage-preservation institute based in a restored villa, Bin Mater House, in Muharraq, the historic district near Manama, the capital of Bahrain.

|

| Melding sounds from ‘ud, violin and drums, members of the Ensemble Muhammad bin Faris help keep alive the sawt tradition of the eastern Arabian Peninsula, together with musicians playing the qanun (Arab zither), ney (woodwind flute) and electric keyboard, all of which support the Ensemble’s vocalists. |

A resident band, the Ensemble Muhammad bin Faris, performs songs from the sawt tradition. The group tours internationally, and although it can comprise up to 14 musicians, on a typical Thursday night, a smaller configuration performs—a singer and ‘ud player, a violinist and players of the qanun (Arab zither), electric piano, ney (woodwind flute) and a variety of drums.

With all those instruments, the sawt arrangements are very different from what you might hear in a private gathering. The heart of sawt is here—the singer accompanying himself on the ‘ud and the propulsive rhythms—but the arrangements are more elaborate, and the sound is what you might call “pan-Arab popular.” The use of western instruments and innovative rhythms, like an Arabized version of the rhumba, suggest Egyptian influence.

|

| The drummers of the Ensemble Muhammad bin Faris know their music by heart, just as others know the patterns of clapping that are no less a part of sawt. An instrumental prelude is followed by a song, and then a tawshihah, or chorus. |

The aim of the ensemble is to keep the sawt tradition alive by modernizing it. Most of the songs it plays would be familiar to performers in a majlis, for they draw on the same repertoire and the same tradition. That said, a performance by the Ensemble invites the question of whether or not this modernized sawt is authentic.

Here, again, a comparison with American blues is helpful: While purists might maintain that authentic blues comes only from a man in the Mississippi Delta playing an acoustic guitar and singing, others would respond that B. B. King playing electric guitar with a big band in a New York City theater is no less “authentic.” To survive and grow, traditions evolve and draw in new elements, leaving determinations of authenticity with individual listeners.

|

| Vocalist and ‘ud player Khalifa al-Jumeiri concentrates as a song begins. |

Certainly, in the Ensemble Muhammad bin Faris the old style of sawt asserts itself. Although the distinction between “audience” and “performer” is imposed by the design of the auditorium itself, in which the band plays on a stage and the audience is arranged in seats, the sawt spectators don’t sit quietly. There are the same calls to the musicians, the same singing along and almost as much rhythmic clapping. And it’s common for one or two men to leave their seats and dance in front of the musicians, as if they were at a musical evening among friends.

Bin Faris himself is still famous, not just in Bahrain but also throughout the Gulf. Next door to the auditorium is the house in which he lived—a lovely, old-fashioned Bahraini building that the Shaikh Ebrahim Center has restored and made into a small museum commemorating his life and career. It houses his instruments, his 78-rpm discs and other memorabilia.

Muharraq can be thought of as the cradle of sawt in Bahrain. Not only was bin Faris born here, but so were many other great sawt players, including the violinist and ‘ud player ‘Aref Busheiri, the current leader of the Ensemble Muhammad bin Faris. Most people know Muharraq as the location of Bahrain’s airport, but its origins date back 5,000 years. It was the capital of Bahrain until 1923, when the British moved government headquarters to Manama. Today it is a densely populated, urban area of no more than about four square kilometers (1.5 sq mi), yet with nearly 200,000 inhabitants. It is divided into quarters called firjan, and it is said that a native Muharraqi can tell which one a person comes from by his or her accent. It was here that in past centuries pearling merchants and the ruling family built their houses, and the Shaikh Ebrahim Center has restored some 10 of them, including bin Faris’s.

Muhammad bin Faris Al Khalifah, to give him his full name, was born in 1895 into the ruling family of Bahrain, grandson of Shaykh Muhammad bin Khalifah, who ruled from 1843 to 1868. As a teenager, he learned music from his brother, but later he traveled to Bombay to follow his musical mentor, ‘Abd al-Rahim al-‘Asiri. There, he joined a large population of expatriate Arabs, mostly Yemenis who worked as mariners or as soldiers for the British administration.

This was an unusual path for a young man of his background, and he is often described as something of a black sheep. But his sojourn in Bombay broadened his musical horizons and allowed him to develop his own style of sawt, write his own new compositions and add to the corpus of sawt songs.

This was an unusual path for a young man of his background, and he is often described as something of a black sheep. But his sojourn in Bombay broadened his musical horizons and allowed him to develop his own style of sawt, write his own new compositions and add to the corpus of sawt songs.

On his return to Bahrain, he was much in demand as a singer. He acquired two students who were to join him among the greats of Bahraini popular music in the 20th century: Muhammad Zuwayyid and Dhahi al-Walid. Among devotees of sawt, bin Faris and al-Walid are often discussed together because of their turbulent relationship.

Although al-Walid began as bin Faris’s student, he became his teacher’s colleague and, later, his competitor. They were a mismatched pair: while bin Faris belonged to the ruling family, al-Walid was the son of an East African slave. Bin Faris chafed at having to treat al-Walid as an equal, especially when al-Walid surpassed him musically. It is said that bin Faris, who died in 1947, would rehearse his songs in secret so that al-Walid would not hear them and produce better versions.

|

| Like American blues, sawt combines lyrics that often address longings and hardships with complex, cathartic rhythms—to the delight of participant-listeners of all ages. |

While the founding of sawt lay with Abdallah al-Faraj in Kuwait, the style was refined and popularized by these later performers—who had the good fortune to stand at the height of their careers when the commercial recording industry took root in the Middle East.

In the 1920s and ’30s, the economies of the Gulf were growing with the appearance of the oil industry, and there was money to spend on newfangled entertainment such as phonographs. European companies like London-based His Master’s Voice knew that to sell phonographs in new markets like the Gulf, they needed to offer recordings people would want to play. This meant recording local artists as part of the phonograph companies’ commercial strategy, and thanks to this, we have a substantial number of recordings of the popular music of this period.

|

| Cradle of sawt and home to some 200,000 people as well as the Muhammad bin Faris house museum, Muharraq is one of the most historic cities of Bahrain. |

The first Gulf artist to make commercial recordings was ‘Abd al-Latif al-Kuwaiti, who in 1927 recorded 10 songs in Baghdad for the Lebanese company Baidophon (the label that also recorded the great Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum) and later for other companies. The popularity of these recordings encouraged other labels to jump into the market and record other Gulf artists, including, in 1929 or 1930, bin Faris’s student Muhammad Zuwayyid and, in 1932, Muhammad bin Faris and Dhahi al-Walid.

It would be misleading to discuss sawt with reference to musicians from just one or two countries. It’s part of the essence of sawt that it ignores national boundaries; it drew influences from many places and, although born in the urban salons of Kuwait, it harks back much farther. It came of age as a music of the mariners and traders who traveled throughout the region, and it drew influences from all over the Gulf and the Indian Ocean. The music of Salim Rashid Suri of Oman is a good example.

Born around 1910 in Sur, an Omani port town that traded with Yemen, East Africa, Zanzibar, India and other ports in the western Gulf, he showed an early interest in music, but was discouraged by his family from making a career of it. Indeed, it is said that his brother threatened him with a gun to make him renounce music. He worked as a sailor and eventually settled in Bombay, where he learned sawt from other musicians and from recordings of ‘Abd al-Latif al-Kuwaiti.

There he established a reputation as a singer, and he became popular among expatriate Arabs. In the 1930s, a local division of His Master’s Voice approached him, and he made a number of recordings. He also recorded for other labels. By this time, Suri was working as a boiler controller on steamships, and he later worked with Arab traders in Bombay as a mercantile broker and translator. After Indian independence in 1948, he settled in Bahrain, where by the 1960s he had started his own recording label, Salimphone, named, immodestly, after himself.

|

| The museum, which stands on the site of his old home, honors bin Faris’s music and recording legacy. |

Salimphone made recordings by, among others, Muhammad bin Faris. The label did not survive the recording industry’s mid-century transition to 45-rpm records, and Suri returned home to Oman in 1971 and died there in 1979. In his final years, he received recognition as a great singer: He performed on Omani television, and he was appointed a consultant on cultural affairs by the country’s ruler, Sultan Qaboos bin Sa‘id.

Suri was a sawt traditionalist. He wrote his own songs and he didn’t like to reinterpret the classics. “He sang it exactly like it was,” said his son, Sa‘id Salim ‘Ali Suri. “He never made any changes.”

The great figures of sawt are the backbone of the tradition, and the tradition is still alive through the songs that these musicians sang and recorded, and among those who still perform sawt. But in recent decades, with the arrival of digital media and the seemingly omnipresent dominance of pan-Arab pop stars—fueled, ironically, by the Sawt al-Khaleej network—no new, great figure has emerged to take a place among the sawt masters, most of whom had died by 1980. (The last musician to join was arguably Awad Dookhi of Kuwait, who died in 1979.) And today, no one seems to be writing new sawt songs.

|

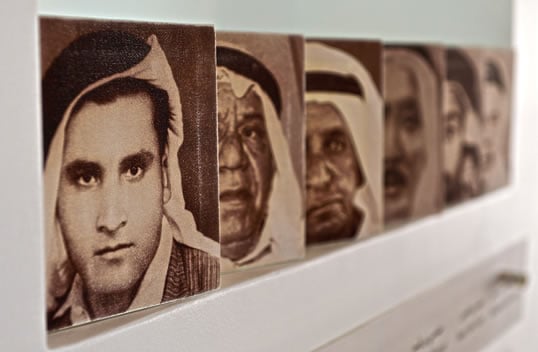

| Portraits along a wall in the Muhammad bin Faris house museum in Muharraq show prominent Bahraini folk musicians and singers, including, from left, Ali Khalid, Yousif Fony and Muhammad Zuwayyid. |

Many years ago, when researching popular music in Oman, I asked the proprietor of a cassette shop for recordings of sawt. “It is music for old men,” he told me dismissively. There is some truth in this. While the Ensemble Muhammad bin Faris seeks to modernize sawt, there are many devotees who welcome such innovations but who still want to preserve the old style, as sawt was recorded in the 1930s and ’40s. As the Bahraini singer Ahmad Jumeiri told me, sawt played simply, in a private gathering, is “the real sawt.”

Wherever sawt is performed today, Gulf music echoes down the years, from the voices of pearl divers and mariners improvising aboard their boats to weekly live sessions in Muharraq. As a Bahraini enthusiast said, “If you listen to a sawt singer now, you will hear Muhammad Zuwayyid, and in Muhammad Zuwayyid you will hear Muhammad bin Faris, and in Muhammad bin Faris you will hear Abdallah al-Faraj. And in Abdallah al-Faraj you will hear the ancient way of singing. You will hear them all in a sawt singer now.”

|

Edward Fox (www.edwardfox.co.uk) is the author of Palestine Twilight: The Murder of Dr. Albert Glock and the Archaeology of the Holy Land (Harper Collins, 2001) and other books. He lives in London. |

| Photojournalist Hatim Oweida (hatim.oweida@aramco.com) covered international news from London for 22 years. He is Saudi Aramco’s chief photographer in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. |