|

|

| LEFT: JÖRG P. ANDERS / KUPFERSTICHKABINETT, STAATLICHE MUSEEN / BPK / ART RESOURCE RIGHT: MELCHIOR LORCK / PRIVATE COLLECTION / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES; |

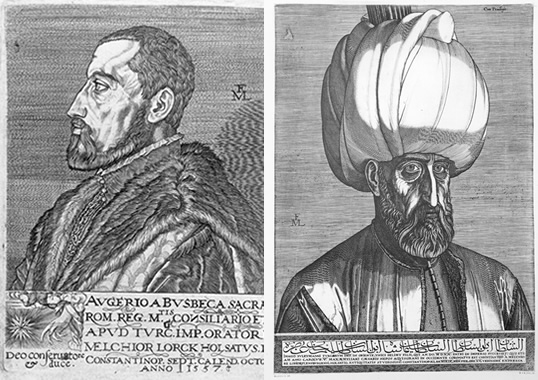

| Left: Ogier Ghiselan de Busbecq was 32 when he met 60-year-old Suleiman the Magnificent, right, and the two held their first frosty peace talks in Amasya, Turkey, in 1555. Busbecq’s long trip from Vienna allowed him to engage in his favorite pastimes: visiting classical ruins, collecting ancient coins and manuscripts and documenting all that he saw. Suleiman substantially increased the size of the Ottoman Empire during his 46-year reign, pushing to the gates of Vienna, the Hapsburg capital, in 1529. The Hapburgs and the Ottomans jockeyed for territory in the Balkans after that, both on the battlefield and through diplomacy. |

When Ogier Ghiselan de Busbecq was born in the Flemish town of Comines near the village of Busbecq in 1522, few would have predicted the role he would play as an intermediary between his fellow Europeans and their imperial neighbors, the Ottoman Turks. As the illegitimate son of the Count of Busbecq, a nobleman in the court of Ferdinand i, the Hapsburg archduke of Austria, his birth was not particularly propitious.

|

| JOSEF KISS AND FRIEDRICH MAYRHOFER / DE AGOSTINI PICTURE LIBRARY / A. DAGLI ORTI / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES (DETAIL) |

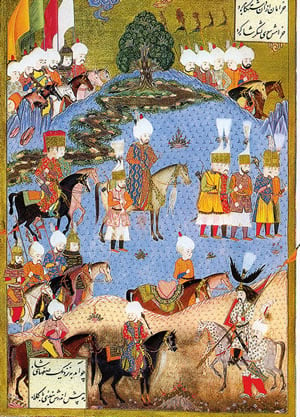

| Ferdinand i, Hapsburg archduke of Austria, dispatched Busbecq to make a peace agreement with Suleiman the Magnificent. The Hapsburgs and the Ottomans were contesting Transylvania, then on the border between East and West. |

n time, however, he would earn a name for himself not only as a diplomat to the court of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, but also as a respected writer. For an audience eager to know its geopolitical rival, military foe and occasional ally, his published correspondence provided a uniquely candid and popular “insider’s view” of the workings of the most powerful empire of the day.

n time, however, he would earn a name for himself not only as a diplomat to the court of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, but also as a respected writer. For an audience eager to know its geopolitical rival, military foe and occasional ally, his published correspondence provided a uniquely candid and popular “insider’s view” of the workings of the most powerful empire of the day.

At the time of Busbecq’s birth, western Europeans were looking warily to the East. It was within living memory that in 1453 the Ottomans under Mehmed ii captured the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (today’s Istanbul). One year before the boy’s birth, in 1521, Mehmed’s great-grandson Suleiman conquered Belgrade, which put the Hungarian capital of Buda (now Budapest) within his sights. Eight years after that, Ottoman forces were besieging the gates of Vienna.

The Turkish advance was halted, but their power was feared and the Hapsburg-Ottoman continental rivalry endured, both on the battlefield and through diplomacy. As in many campaigns, propaganda was a weapon. In western chronicles of the era, “the inhumanity of the Turks was emphasized above all else, and the stereotyped Turk, villainous, savage and bloodthirsty … was firmly established in the historical traditions of the West,” wrote Sıla enlen of Ankara University in a 2005 paper. For their part, the Turks looked upon the Latin Christians with disdain.

It was Busbecq who offered a more balanced view of the Ottomans to his fellow Europeans, based on firsthand experience. As Archduke Ferdinand’s envoy to Turkey from 1554 to 1562, he wrote a series of letters to his friend Nicholas Michault, who was at that time a fellow Hapsburg diplomat assigned to the Portuguese court. A keen observer of both nature and human nature, Busbecq marveled at the beauty of the Ottoman lands. He delighted in the Turks’ kindness toward animals, and he greatly admired the discipline and fortitude of the common Turkish soldier. He was also sincerely impressed by the grandeur of the Ottoman court and of a bureaucracy he found staffed by men who were valued for their talent rather than their family ties.

|

| ALI AMIR BEG / TOPKAPI PALACE MUSEUM / ARCHIVES CHARMET / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES |

| Louis ii, king of Hungary, is shown holding counsel with his nobles prior to the Battle of Mohacs in 1526. He lost the battle—and his life—to the forces of Suleiman. |

Yet for all his admiration for the Ottoman systems of society and government, Busbecq was clear-eyed about the threat Suleiman posed to a less-than-united western Europe. “On their side are the resources of a mighty empire, strength unimpaired, experience and practice in fighting, a veteran soldiery, habituation to victory, endurance of toil, unity, order, discipline, frugality and watchfulness,” he wrote. “On our side is public poverty, private luxury, impaired strength, broken spirit, lack of endurance and training…. If there is war can we doubt what the result will be?”

Busbecq was relatively new to the role of diplomat when he set out as the Hapsburg ambassador to Turkey in the autumn of 1554. His only previous assignment had been earlier that year to England, where he served as Ferdinand’s representative at the wedding of Ferdinand’s nephew, Philip ii of Spain, to Mary Tudor. His new posting promised to be far less sanguine: Ferdinand had invaded the Ottoman protectorate of Transylvania in 1551, breaking a four-year truce that had stanched almost three decades of intermittent war between Hungary and Turkey. Suleiman was angry.

Indeed, upon hearing the news of Ferdinand’s incursion, Suleiman had thrown the previous Hapsburg ambassador into jail, where he remained for two years before being allowed to return home, only to die soon afterward. It was now up to Busbecq to repair deeply frayed relations and conclude a new treaty acceptable to both Suleiman and Ferdinand. The task would prove slow and exceedingly tedious. But Busbecq was a patient man, and during the seven years he spent in Turkey (they were not consecutive years: He served from 1554-1555 and again from 1556-1562), he grew to understand and appreciate the qualities that had brought the Ottomans to the apex of their power.

When Suleiman came to the throne in 1520, his empire included Anatolia, most of Egypt, Syria and the Balkan states. By the time of his death in 1566, he had extended Ottoman control from Budapest on the Danube to Aswan on the Nile, and from the Euphrates River through North Africa almost to Gibraltar.

|

| BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES |

| Colorfully garbed Janissaries, the special forces of the Ottomans, impressed Busbecq with their fine appearance when he viewed them on his arrival in Amasya in May 1555. |

Suleiman also took sides in struggles within Europe: In 1536, he allied with France against the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles v, and Suleiman received help from the French king in his ongoing confrontation with the Hapsburg confederation. More direct help came from the legendary admiral of his fleet, Hayreddin Barbarossa, who won the critical victories at sea that secured Suleiman’s control of the Mediterranean.

Yet, as successful as his military campaigns were, Suleiman’s interests extended beyond conquest. Known as Suleiman Kanuni (Lawgiver) in his domains, he reorganized Ottoman canon law and greatly expanded the rights of the empire’s non-Muslim populations, including Christians and Jews. Nor did he neglect the arts: During his reign, Ottoman architecture reached its zenith and Ottoman silk, glass and Iznik ceramics were coveted throughout Europe for their beautiful patterns and fine workmanship.

Ottoman education, though largely limited to those who would later administer the empire, was also of a high standard. The curriculum included poetry, literature, history, law and religion, and students were taught to read and write in Turkish, Arabic and Persian.

By contrast, western Europe was a conglomeration of often-hostile states whose anchor, the Catholic faith, had been shaken by the Reformation. Yet Europe, too, had its glories, not least the unrivaled arts of the Renaissance. The Venetian painters Bellini and Titian were well known to the Ottoman sultans, as were the Renaissance monarchs: Henry viii of England and his daughter Elizabeth i; Francis i of France; Charles v and his son Philip ii; and—especially well known to Suleiman—Charles’s younger brother, Ferdinand i, himself Holy Roman Emperor from 1558 to 1564.

As in Turkey, education in Europe was reserved for the few. Busbecq was awarded a degree in advanced Latin studies at the University of Louvain in Belgium and continued scholarly pursuits in Paris, Venice, Bologna and Padua, keeping remarkably complete notes of all he saw and learned. These notes provided the foundation for the letters he wrote to Michault.

Busbecq and Michault had attended school together and, as diplomats, they understood the difficulties inherent in maintaining a pleasant and persuasive presence no matter how difficult the negotiations at hand. However, Busbecq’s letters extended well beyond the confines of his workday.

His first letter dates to September 1, 1555, shortly after he had returned to Vienna from his initial audience with the sultan, which took place in Amasya, in north-central Turkey, a city so far from the Hapsburg capital—some 1,850 kilometers—that he may have been the first European to visit that area since the Seljuk Turks conquered it late in the ninth century.

|

| TOPKAPI PALACE MUSEUM / DOST YAYINLARI / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES |

| This map of 16th-century Constantinople shows the western side of the Ottoman capital, with the Golden Horn running through the center and up the left-hand side. A small portion of the city’s Asian side is shown at right. Busbecq lived in Elçï Han, near the Atik Ali mosque, as circled, above. |

The trip began well. Barely had Busbecq crossed into Turkish territories near Gran (today’s Esztergom) in Hungary than he found himself in the midst of an escort of 150 splendidly arrayed cavalrymen and their officers, whom he found surprisingly gracious.

Busbecq journeyed with this handsome escort to the capital at Buda, a city once renowned for its decorative palaces and glittering lifestyle, but more recently known as the home of Hungary’s naïve young King Louis ii, who ruled from 1516 to 1526. Perhaps overvaluing his country’s defenses, Louis had neglected to renew a long-standing peace treaty with the Turks. It was a catastrophic oversight: In 1526, Suleiman all but annihilated the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohacs, where Louis, only 20 and childless, lost his life.

By treaty, his brother-in-law, Ferdinand of Hapsburg, should have ascended the throne. But Hungarian electors, wishing to remain independent of Hapsburg influence, selected instead John Zápolya of Transylvania to wear the crown. In 1529, Zápolya allied with Suleiman to protect himself and his realm from Ferdinand. In that, Suleiman shared an interest: The last thing he wanted was to have his archrivals, the Hapsburgs, as next-door neighbors.

All remained quiet for a decade or so, until 1540, when Zápolya died. Ferdinand then attacked and quickly captured Buda. Zápolya’s widow, the queen dowager for her infant son, turned to Suleiman, who marched on the city in 1541 and easily took it, making eastern Hungary an Ottoman protectorate.

This was a state of affairs Ferdinand could not abide. Incursion after incursion followed until a series of defeats at Ottoman hands forced Ferdinand and his powerful brother, Charles v, to sign a peace treaty with Suleiman. That was in 1547. But the prize of a united Hungary was too great a dream for Ferdinand to relinquish so easily: In 1551 he marched into Transylvania again, and it was the repercussions of this that Busbecq was sent to sort out.

That particular task lay in the future, however. In 1554, as Busbecq undertook his assignment, he meant to enjoy his journey, taking care to note all he saw and learned. He was particularly taken by the flowers, which he found in profusion in Adrianople (today’s Edirne, on Turkey’s border with Greece and Bulgaria). But even Adrianople was overshadowed by Constantinople, which delighted Busbecq with its wealth of ancient monuments and marvelous views of the surrounding seas and magnificent countryside.

|

| TOPKAPI PALACE / PICTURES FROM HISTORY / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES |

| Sultan Suleiman personally led his armies to Transylvania, the Caspian and much of the Middle East. This portrait of him with his troops was made in 1561. |

Had Suleiman been in residence, Busbecq’s journey would have ended here. But the Sultan was negotiating a peace treaty with the Safavid ruler of Persia in Amasya, some 565 kilometers away, and he asked the diplomat to join him there. For Busbecq, the 13-day journey was filled with pleasures. Here was the chance to view the classical ruins he dearly loved, and to collect ancient coins, manuscripts and inscriptions.

It also gave him the chance to see the local sheep whose “very fat and weighty tails,” he wrote, could “grow so big in some old sheep, that they are forced to lay them upon a plank, running on two little wheels, so they may draw them after them, not being otherwise able to trail them along.”

Busbecq arrived in Amasya on April 7, 1555. Following the customary interview with the attendant pashas, he met the sultan, who was not pleased by what he heard. Suleiman “listened to the recital of my message,” Busbecq wrote, “but, as it did not correspond with his expectations (for the demands of my master were full of dignity and independence, and, therefore, far from acceptable to one who thought that his slightest wishes ought to be obeyed), he assumed an expression of disdain, and merely answered, ‘Giusel, giusel,’ that is, ‘well, well.’ We were then dismissed to our lodging.”

In Amasya, Busbecq witnessed a large gathering of the Ottoman military for the first time. Greatly impressed by the troops’ discipline and colorful dress, he was more impressed still by their leaders who, he concluded, had the ability and training to perform their duties with such skill and efficiency that “the Turks succeed in all that they attempt and are a dominating race and daily extend the bounds of their rule.”

On June 2, Busbecq and his delegation paid a farewell visit to Suleiman. He presented them with a “dispatch wrapped up in cloth of gold and sealed,” but rather than the peace treaty Busbecq hoped for, he wrote, it offered only a six-month truce with the request that “a further reply [be] brought back.”

Busbecq arrived in Vienna in August 1555, exhausted by the journey. In November, he set out again with Ferdinand’s reply, arriving to a reception far less cordial than the previous year. After learning that Ferdinand continued to assert his right to the Hungarian throne, the pashas refused to grant Busbecq an audience with the sultan, cautioning that “we should keep quiet and not arouse the sleeping lion nor hasten on the troubles which were sure to come upon us soon enough,” he wrote.

In fact, as Busbecq reported in his letter of July 14, 1556, barely had he and his staff reached their embassy than they were confined and treated “in every way almost as prisoners instead of ambassadors. This has continued now for six months, and we have no idea what the future has in store for us.’’

Busbecq’s third letter is dated June 1, 1560. He noted that his colleagues had been allowed to leave Constantinople at the end of August 1557 and that he might have joined them had he wished. But he stayed on, believing that if he departed it might suggest that peace negotiations had come to an end, an impression to be avoided at all costs as it might make “a terrible war inevitable.”

In response to a query from Michault, Busbecq reported that the only time he left the embassy was when he had dispatches from Ferdinand to present to the sultan. This occurred only two or three times a year, “So I stay at home and hold communion with those old friends, my books; they are my companions and the joy of my life,” he wrote. He noted, however, that he had other companions in the form of a large menagerie that included everything from well-bred horses to a variety of weasels.

This quiet life soon changed, however, as Busbecq told Michault in his fourth letter, written after he had returned to Vienna in 1562.

The changes began with a distressing event. For more than 30 years Suleiman and Charles v had vied for control of the Mediterranean, a rivalry pursued by Charles’s son, Philip ii, when he succeeded his father to the Spanish throne in 1556. In 1559, Philip concluded a plan to take the port of Tripoli (in present-day Libya) and sent a fleet of 50 galleys with some 6,000 soldiers to the proposed staging point, the island of Djerba, off the coast of Tunisia.

But things did not go well. Barely had the Spanish captured Djerba and erected a fort than they were taken unawares by the Turks, who destroyed their galleys and cut off their water supply. Only the commanders survived, to be sent as trophies to Suleiman. On October 1, 1660, the victorious Ottoman fleet rounded Seraglio Point below the sultan’s palace and sailed into the Golden Horn. It was a sight Busbecq would never forget.

The half-starved Spanish officers were displayed on the poop deck of the brightly colored Turkish flagship while their captured galleys were “towed along, stripped of their oars and bulwarks and reduced to mere hulks, so that in this condition they might seem small, shapeless and contemptible in comparison with the Turkish vessels,” Busbecq wrote.

|

| PRIVATE COLLECTION / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES |

| European ambassadors sit, upper right, with merchants, acrobats and cavalry, in this 16th-century scene dating to the reign of Suleiman’s grandson Murad iii. |

Busbecq felt it his duty to help the prisoners as best he could. In addition to supplying them with boiled mutton, he fulfilled their requests for blankets, shoes, cloaks and even wine. A more expensive request came from those “who wished me to act as surety for their ransom,” he noted. Busbecq loaned money to them all, confiding to Michault that even if he were not repaid, “I must not mind; a good action performed for a good man is never wholly lost. Most of them will certainly keep their word.”

Busbecq’s first objective, however, was to negotiate the long-sought peace treaty with Suleiman’s grand vizier, Rustem Pasha, whom he described as a man who “wished his words to be looked upon as orders” and who “never deviated from his customary rudeness.” Busbecq became particularly annoyed with Rustem Pasha when plague struck Constantinople and the vizier would not allow Busbecq and his household staff to retire to a safer place.

Then, quite unexpectedly, Rustem Pasha died of dropsy. He was replaced by Ali Pasha, whom Busbecq found to be “a delightfully intelligent person, and by no means lacking in humanity.”

Ali Pasha immediately allowed Busbecq to retire to a suitable place until the plague abated. The diplomat chose the little island of Prinkipo, where he delighted in fishing, hiking and simply breathing the fresh air.

As Ali Pasha had also retired to the island, the two became friends and, once they returned to Constantinople, soon negotiated a truce, under which the current borders would stand and Ferdinand would pay a small tribute. Peace—for a time at least—had been secured.

By August 1562, Busbecq was ready to return to Vienna. As a parting gift, Ali Pasha gave him three thoroughbred horses of far higher quality than those he could have obtained on his own. In return, Busbecq gave Ali Pasha a coat of mail ample enough “to fit his tall and stout frame” and a charger sturdy enough “to carry his great weight.”

Following his return to Vienna, Busbecq continued to serve as a diplomat for Ferdinand, and later for Ferdinand’s son Maximillian ii and grandson Rudolf ii. In 1592, at the age of 71, he set out from an assignment in Paris to visit his beloved home in Busbecq. His route took him through Normandy where soldiers engaged in the region’s civil war ignored Busbecq’s diplomatic status and seized him. The fracas was too much for the aging Busbecq, and he died 11 days later, on October 28. Busbecq was buried in the church in St. Germain, Normandy, but his heart was enclosed in a leaden casket and placed in the family tomb at Busbecq.

Busbecq left an impressive legacy. His pursuit of antiquities generated a wealth of knowledge for western Europe about classical Greece and Rome. He collected 240 classical manuscripts, which he donated to the Vienna Imperial Library (now the Austrian National Library), together with a valuable coin collection. He also discovered in Constantinople a spectacular 500-year-old copy of De Materia Medica, the remarkable compendium of medicinal herbs by the first-century ce Greek physician Dioscorides that was the cornerstone of herbal therapeutic knowledge for centuries. Acquired by Maximillian ii on Busbecq’s recommendation, it remains one of the finest known examples of a late-antique scientific text.

|

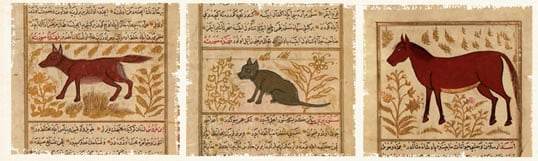

| WALTERS ART MUSEUM (3) |

| Busbecq was fond of animals, and he kept and wrote about many, from wolves to horses to ducks. These later Turkish miniatures show a jackal, a cat and a horse. |

Busbecq is also credited with introducing the llac to the West, and some say the tulip as well. He even brought back part of his menagerie, including six she-camels, his beautiful horses and a large tame mongoose called an ichneumon. Yet, as precious as these gifts were, the name Busbecq is most closely associated with his extraordinary letters.

The first letter was published in the original Latin as Itinera Constantinopolitanum et Amasianum (Travels to Constantinople and Amasya) in 1581, and all four letters appeared in 1589. They went through several printings and were translated into French, German, Dutch, Spanish and English as The Turkish Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, which remains in print today.

For many years, they were among the most popular books in Europe. Even now, those who wish to know about the 16th-century Ottoman world turn to Busbecq to see, as he did, the impressive parades, the colorful costumes, the gaily caparisoned horses and the ubiquitous camels who “kneel in a circle with their heads close together, eating and drinking with the utmost good will out of the same manger or basin, content with the scantiest fare.”

In his time, no one described Ottoman Turkey better.

|

Jane Waldron Grutz (waldrongrutz@gmail.com) is a former staff writer for Saudi Aramco who now divides her time between Houston and London. She is a regular contributor to AramcoWorld. |