t a time when the greatest speed humans could reach was astride a galloping horse, to travel 120,000 kilometers, or 75,000 miles, in 30 years was a remarkable feat. At a steady pace, it would have worked out to a bit under 11 kilometers (7 mi) a day for almost 11,000 days.

|

| Ibn Battuta does not describe his early life in the Rihla nor, for that matter, much of his personal life at all—such matters would have been inappropriate for the literary memoir he was dictating. We know he was trained as a qadi, or judge, in the Maliki tradition of jurisprudence, which is one of the four major schools of Islamic legal thought that codified, interpreted and adjudicated shar’ia, or Islamic law. He would have studied in mosques and in the homes of his teachers, and at an early age he would have memorized the Qur’an. |

The man who traveled that distance was, according to his chronicler, "the traveler of the age." He was not the Venetian Marco Polo, but Ibn Battuta of Tangier, who set out eastward in 1325, the year after Polo died. Ibn Battuta's wanderings stretched from Fez to Beijing, and although he resolved not to travel the same path more than once, he made four Hajj pilgrimages to Makkah, in addition to crossing what, on a modern map, would be more than 40 countries. He met some 60 heads of state—and served as advisor to two dozen of them. His travel memoir, known as the Rihla, written after his journeys were complete, names more than 2000 people whom he met or whose tombs he visited. His descriptions of life in Turkey, Central Asia, East and West Africa, the Maldives, the Malay Peninsula and parts of India are a leading source of contemporary knowledge about those areas, and in some cases they are the only source. His word-portraits of sovereigns, ministers and other powerful men are often uniquely astute, and are all the more intimate for being colored by his personal experiences and opinions.

Ibn Battuta was born in the port town of Tangier, then an important debarkation point for travelers to Gibraltar, beyond which lay al-Andalus, Arab Spain, by then reduced from its former extent to include only the brilliant but beleaguered kingdom of Granada.

At age 21, Ibn Battuta set forth at a propitious time in history. The concept of the 'umma, the brotherhood of all believers that transcends tribe and race, had spiritually unified the Muslim world, which stretched from the Atlantic eastward to the Pacific. Islam was the world's most sophisticated civilization during the entire millennium following the fall of Rome. Its finest period was the 800 years between Islam's great first expansion in the seventh and eighth centuries and the advent of European transoceanic mercantilism in the 15th century. During that time, Islam had breathed new life into the sciences, commerce, the arts, literature, law and governance.

Thus the early 14th century, an era remarkable in Europe for gore and misery, was a magnificent time in Dar al-Islam, the Muslim world. A dozen or more varied forms of Islamic culture existed, all sharing the core values taught in the Qur'an, all influencing each other through the constant traffic of scholars, doctors, artists, craftsmen, traders and proselytizing mystics. It was an era of superb buildings, both secular and sacred, a time of intellect and scholarship, of the stability of a single faith and law regulating everyday behavior, of powerful economic inventions such as joint ventures, checks and letters of credit. Ibn Battuta became the first and perhaps the only man to see this world nearly in its entirety

n Tangier, Shams al-Din Abu 'Abdallah Muhammad ibn 'Abdallah ibn Muhammad ibn Ibrahim ibn Muhammad ibn Ibrahim ibn Yusuf al-Lawati al-Tanji Ibn Battuta was born into a well-established family of qadis (judges) on February 25, 1304, the year 723 of the Muslim calendar. Beyond the names of his father and grandfathers that are part of his own name, we know little about his family or his biography, for the Rihla is virtually our sole source of knowledge of him, and it rarely mentions family matters, which would have been considered private. But we can surmise that, like most children of his time, Ibn Battuta would have started school at the age of six, and his literate life would have begun with the Qur'an. His class—held in a mosque or at a teacher's home—would in all likelihood have been funded by a waqf, a religious philanthropic trust or foundation, into which the pious could channel their obligatory charitable giving (zakat). Ibn Battuta's parents would have paid his teachers an additional modest sum, in installments due when the boy achieved certain well-defined milestones.

n Tangier, Shams al-Din Abu 'Abdallah Muhammad ibn 'Abdallah ibn Muhammad ibn Ibrahim ibn Muhammad ibn Ibrahim ibn Yusuf al-Lawati al-Tanji Ibn Battuta was born into a well-established family of qadis (judges) on February 25, 1304, the year 723 of the Muslim calendar. Beyond the names of his father and grandfathers that are part of his own name, we know little about his family or his biography, for the Rihla is virtually our sole source of knowledge of him, and it rarely mentions family matters, which would have been considered private. But we can surmise that, like most children of his time, Ibn Battuta would have started school at the age of six, and his literate life would have begun with the Qur'an. His class—held in a mosque or at a teacher's home—would in all likelihood have been funded by a waqf, a religious philanthropic trust or foundation, into which the pious could channel their obligatory charitable giving (zakat). Ibn Battuta's parents would have paid his teachers an additional modest sum, in installments due when the boy achieved certain well-defined milestones.

| Ibn Battuta lived during a rekindling of Islamic civilization variously called the Post-Mongol Renaissance or the Pax Mongolica. It began in the late 1200’s following nearly a century of Mongol invasion, depredation and ensuing economic depression in China, Central Asia, Russia, Persia and the Middle East. By the early 14th century, much of this territory was part of the largest unified empire in history—but one in which the rulers, formerly pagan, had embraced Islam. For the most part, they had turned from conquest to trade, and this led to the restoration of Persia and the Silk Roads cities of Central Asia to their hemispherically central roles. Thus at the time Ibn Battuta set out from Tangier for Makkah, the exchange, even over great distances, of scholars, jurists and other members of the educated Islamic elite was at a historic peak. Travelers like Ibn Battuta could expect to meet other educated gentlemen, with like manners and common values, from all corners of the known world. News would travel with fleets and caravans from the Atlantic in the west to the Pacific in the East—the only boundaries of Dar al-Islam. |

The curriculum of a 14th-century classroom would, in some ways, look remarkably up to date today. Learning, in the first instance, meant the Qur'an, but for urban children especially it did not stop there. Elementary arithmetic was obligatory, for everyone needed to be able to carry on everyday transactions. Secondary education transmitted the bulk of what are now termed vocational skills, including the more complex calculations needed for such practical purposes as the division of an estate among heirs, the surveying of land, or the distribution of profits from a commercial venture. Tertiary or higher education, however, was as much about character development as the subjects taught. Foremost were the refinements of Arabic grammar, since Arabic was not only the language of the Qur'an but also the language of all educated, let alone scholarly, discourse, and the Muslim lingua franca from Timbuktu to Canton. Other subjects taught would have included history, ethics, law, geography and at least some of the military arts.

There were differences from today's practices, too. Young Ibn Battuta's most important goal, as for most young students of his time, was to learn the Qur'an by heart: He refers many times in the Rihla to reciting the entire Qur'an aloud in one day while traveling—and a few times, when he felt he needed moral stiffening, twice. Knowledge of the Qur'an took precedence over all other intellectual pursuits, and students whose means permitted traveled from one end of Dar al-Islam to the other to learn its subtleties and its interpretation from the wisest men of the day. Every provincial scholar who desired distinction at home aspired to study in Makkah, Madinah, Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo—a kind of scholarly Grand Tour. Wandering scholars were given modest free meals and a place to stay in the madrasas that dotted the Muslim world, or if no better accommodation were available they slept on mosque floors. No institutional degrees existed; instead the student received a certificate from his teachers. The highest accolade was adah, meaning "one who is adept" at manners, taste, wit, grace, gentility, and above all, "knowledge carried lightly."

As one of five major ports along the Strait of Gibraltar, Tangier vibrated with the As one of five major ports along the Strait of Gibraltar, Tangier vibrated with the

hustle and bustle of business and innovation. Yet it was not renowned for scholarship even within Morocco, and it is not surprising that the young student determined to study further in Makkah. Beyond academic credentials, however, Ibn Battuta’s career also demonstrated his knack for traveling on his wits and for putting his ever-growing store of experience to good use—and he seems to have had a remarkable ability to ingratiate himself with authority. |

Ibn Battuta's knowledge of the subtleties of Arabic identified him anywhere as an educated gentleman, but Tangier was not one of the great centers of learning. The knowledge of fiqh, or religious law, that he acquired there might perhaps be described as B-level work at a B-list school. So, armed with his earnest but hardly world-tested knowledge, Ibn Battuta set out eastward from Tangier to make his first Hajj, or pilgrimage, to Makkah. In the words he dictated to his scribe three decades later, one can still detect both youthful excitement and youthful misgiving:

| Ibn Battuta turned his own education and the further knowledge and experience that he gathered on his travels into a respectable and comfortable livelihood. In the early years of his wanderings he found a ready reception as a qadi , or judge, and a legal scholar. In that occupation he served municipal governors and lesser dignitaries when asked, or when he needed the work. Later, his fame as a traveler became itself an asset, and he found himself advising caliphs, sultans, and viziers, who compensated him with emoluments that today’s travel writers can only dream of. |

"I set out alone, having neither fellow-traveler in whose companionship I might find cheer, nor caravan whose party I might join, but swayed by an overmastering impulse within me, and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries [of Makkah and Madinah]. So I braced my resolution to quit all my dear ones...and forsook my home as birds forsake their nests. My parents being yet in the bonds of life, it weighed sorely upon me to part from them, and both they and I were afflicted-with sorrow at this separation."

hirty years were to pass before Ibn Battuta hung up his sandals for good. He set out a pilgrim, probably planning to return to Tangier, but along the way he grew into one of the rarest kinds of travelers: one who voyaged for the sake of voyaging. In the coming years, he would change his itinerary almost on impulse, at the merest hint of the chance to see some new part of Dar al-Islam, to visit a scholar, a revered teacher, or a sultan.

hirty years were to pass before Ibn Battuta hung up his sandals for good. He set out a pilgrim, probably planning to return to Tangier, but along the way he grew into one of the rarest kinds of travelers: one who voyaged for the sake of voyaging. In the coming years, he would change his itinerary almost on impulse, at the merest hint of the chance to see some new part of Dar al-Islam, to visit a scholar, a revered teacher, or a sultan.

Time after time he set out for a destination in a roundabout, or even an entirely opposite, direction. Once, a mere 40 days by sail from India but facing a months-long wait for favorable winds, he instead set out on a land route that took him there by way of Turkey, a Central Asia and the Hindu Kush, a journey of more than a year.

Hints of the persistence that marked his life appear early on. From Tangier he proceeded east across Mediterranean Morocco and Ifriqiyyah (now Algeria) to Tunis. On the way, two fellow travelers fell ill with a fever. One died; from the other, unscrupulous government agents confiscated his entire estate, which he was carrying, in gold, to his needy heirs. Ibn Battuta himself was so ill that he strapped himself to the saddle of his mule. Yet fare forward he did, determined that "if God decrees my death, it shall be on the road with my face set towards the land of the Hijaz" and Makkah.

The first madrasas were founded at Samarkand and at Khargird in northeastern Iran in the ninth century. Within each were a small mosque, lecture rooms, and quarters for students and teachers. Generally the madrasas were devoted to the teaching one of what by then had evolved into the four schools of Muslim jurisprudence: the Hanafi, Hanbali and Shafi’i, and Ibn Battuta’s own Maliki school. The name of the College of the Booksellers that sheltered Ibn Battuta in Tunis probably indicates that it was supported by the charity of the local booksellers’ guild. |

He also learned early the manners and courtesies of the road:

At last we came to the town of Tunis.... Townsfolk came forward on all sides with greetings and questions to one another. But not a soul said a word of greeting to me, since there was none of them that I knew. I felt so sad at heart on account of my loneliness that I could not restrain the tears that started to my eyes, and wept bitterly. But one of the pilgrims, realizing the cause of my distress, came up to me with a greeting and friendly welcome, and continued to comfort me with friendly talk until I entered the city, where I lodged in the College of the Booksellers.

It was Ibn Battuta's first and last recorded bout of homesickness. The pilgrim's kindness and the hospitality of the College of the Booksellers made for what was literally a rite of passage. His home was now the fraternity of the 'umma, warmed by the company of the educated men, the 'ulama, whom he would meet in palace courts and madrasas wherever he traveled in Dar al-Islam.

In Tunis, Ibn Battuta joined a caravan headed for Alexandria. There, two things happened to him that, as he relates it, set his sights forever on the travels he eventually undertook. In the first,

I met the pious ascetic Burhan al-Din,...whose hospitality I enjoyed for three days. One day he said to me, "I see that you are fond of traveling through foreign lands." I replied, "Yes, I am" (though as yet I had no thoughts of going to such distant lands as India or China). Then he said, "You must certainly visit my brother Farid al-Din in India, and my brother Rukn al-Din in Sind [Pakistan], and my brother Burhan al-Din in China. When you find them, give them greetings from me." I was amazed at his prediction, but the idea of going to these countries once cast into my mind, my journey never ceased until I had met these three and conveyed his greeting to them.

A few days later, while the guest of the pious Shaykh al-Murshidi, Ibn Battuta had a dream:

I was on the wing of a great bird which was flying me toward Makkah, then to Yemen, then eastward, and thereafter going south, then flying far eastward, and finally landing in a dark, green country, where it left me.... Next morning, the Shaykh interpreted it to me, "You will make the Hajj and visit the Tomb [of the Prophet], and you will travel through Yemen, Iraq, the country of the Turks, and India. You will stay there a long time and meet my brother Dilshad the Indian, who will rescue you from a danger into which you will fall." Never since I departed from him have I received aught but good fortune.

The life-saving Dilshad did indeed arrive to rescue Ibn Battuta from danger in India, and the last sentence quoted above must imply that one breathtaking brush with death after another was in fact "good fortune" when compared to the more catastrophic alternative.

![Ibn Battuta does not hint at the size of the annual pilgrimage caravan by which he traveled from Damascus to the Holy Cities of Madinah and Makkah, except at one point to refer to it as “huge.” He describes how it replenished its water supplies in what is now northwestern Saudi Arabia: “Each amir or person of rank has a [private] tank from which his camels and those of his retinue are watered, and their waterbags filled; the rest of the people arrange with the watercarriers [of the oasis] to water the camel and fill the waterskin of each person for a fixed sum of money. The caravan then sets out from Tabuk and pushes on speedily night and day, for fear of this wilderness.”](images/part1/BATTUTA_6.47307.jpg) |

| Ibn Battuta does not hint at the size of the annual pilgrimage caravan by which he traveled from Damascus to the Holy Cities of Madinah and Makkah, except at one point to refer to it as “huge.” He describes how it replenished its water supplies in what is now northwestern Saudi Arabia: “Each amir or person of rank has a [private] tank

from which his camels and those of his retinue are watered, and

their waterbags filled; the rest of the people arrange with the watercarriers [of the oasis] to water the camel and fill the waterskin of each person for a fixed sum of money. The caravan then sets

out from Tabuk and pushes on speedily night and day, for fear

of this wilderness.” |

airo was Ibn Battuta's first taste of Muslim civilization on a grand scale. He entered Egypt at a time when a far-sighted ruler, a good administrative bureaucracy and a strong economy reinforced each other and together encouraged peace, prosperity, and prestige. Egypt held a virtual monopoly on trade with Asia, which did much to enrich the Mamluk regime, swell the sails of middle-class prosperity, and drive forward the ship of state. To the young man from Tangier, it was nothing short of wonderful:

airo was Ibn Battuta's first taste of Muslim civilization on a grand scale. He entered Egypt at a time when a far-sighted ruler, a good administrative bureaucracy and a strong economy reinforced each other and together encouraged peace, prosperity, and prestige. Egypt held a virtual monopoly on trade with Asia, which did much to enrich the Mamluk regime, swell the sails of middle-class prosperity, and drive forward the ship of state. To the young man from Tangier, it was nothing short of wonderful:

It is said that in Cairo there are 12,000 water carriers who transport water on camels, 30,000 hirers of mules and donkeys, and on the Nile 36,000 boats belonging to the sultan and his subjects, which sail upstream to Upper Egypt and downstream to Alexandria and Damietta laden with goods and profitable merchandise of all kinds. On the banks of the Nile opposite Cairo is a place known as The Garden, which is a pleasure park and promenade containing many beautiful gardens, for the people of Cairo are given to pleasure and amusements.... The madrasas cannot be counted for multitude.... The Maristan hospital has no description adequate to its beauties....

But Makkah was still Ibn Battuta's goal. He sailed up the Nile and caravanned east to 'Aydhab on the Red Sea coast, a transit town "brackish of water and flaming of air." Unfortunately, he arrived at a moment when the ruling clan was in revolt against their Mamluk sovereign in Cairo. So, making the best out of the worst—something he became quite adept at—Ibn Battuta returned to Cairo and crossed the Sinai by camel, sojourning in the khans and cities of Palestine and Syria till he reached Damascus, where he could join the annual Hajj caravan to Makkah. The fact that another caravan also left annually from Cairo tells us something of Ibn Battuta's temperament: Rather than endure a brief residence in Cairo, he chose to extend his travels.

Ibn Battuta didn’t travel at a steady pace. A ship could make 150 kilometers (93 mi) of progress, or even more, in a day’s travel with a following wind, but expectations dropped drastically under less favorable conditions. For reasons of security, most overland travel was conducted in caravans, which on the flat could make 65 kilometers (40 mi) a day, but far less in difficult terrain. Thus “a day’s travel” was a relative notion, but in its time it was the most useful measure. Ibn Battuta usually gave distances in “miles,” probably meaning the Arab mile, which was 1.9 kilometers, or 1.19 of today’s land miles. Yet his narrative abounds with varied local measures, such as Egyptian farsakhs (5763 m, 3.5 mi), which were divided into 12,000 ells.

One of the only places where he mentions mileposts is in India: “Dihar [today’s Dhar] is 24 days’ journey from Delhi. All along the road are pillars, on which are carved the number of miles from each pillar to the next. When the traveler desires to know how many miles he has gone or how far it is to the next halting place, he reads the inscriptions on the pillars.” |

In Damascus, one of his first stops was the great mosque, which stands today. He reflected on its pragmatic adaptiveness:

The Friday Mosque, known as the Umayyad Mosque, is the most magnificent in the world, the finest in construction, and the noblest in beauty, grace, and perfection.... The site of the mosque was a [Greek Orthodox] church. When the Muslims captured Damascus, one of their commanders entered from one side by the sword and reached as far as the middle of the church. The other entered peaceably from the eastern side and reached the middle also. So the Muslims made the half of the church which they had entered by force into a mosque, and the half which they had entered by peaceful agreement remained a church.

Later, the Umayyad rulers offered to buy the Christians out, but they refused to sell. The Umayyads then confiscated the building, but quickly made up for this lapse of civility by raising a huge sum of money that was given to the Christians to build a new cathedral.

Mosques were community centers as well as houses of worship. The first ones had been sheltered spaces where the community could come together not only for prayer, but also to discuss public issues. Friday, or congregational, mosques, where the faithful of a whole city or quarter came together to pray, occupied prime locations, and made those locations the most prestigious parts of the city. Near a Friday mosque and its madrasas one could find both the finest wares and the intellectual professionals. Ibn Battuta's description of the Umayyad mosque continues:

The eastern door, called the Jayntn door, is the largest of the doors of the mosque. It has a large passage, leading out to an extensive colonnade, which is entered through a quintuple gateway between six tall columns. Along both sides of this passage are pillars supporting circular galleries, where the cloth merchants, among others, have their shops. Above these are long galleries in which are the shops of the jewelers and booksellers and makers of admirable glassware. In the square adjoining the first door are the stalls of the principal notaries, in each of which there may be five or six witnesses in attendance and a person authorized by the qadi to perform marriage ceremonies. Near these bazaars are the stalls of the stationers who sell paper, pens, and-ink.... To the right as one comes out of the Jayrun door, which is also called "The Door of the Hours," is an upper gallery shaped like a large arch, within which are small open arches furnished with doors, to the number of the hours of the day. These doors are painted green on the inside and yellow on the outside. As each hour of the day passes the green inner side of the door is turned to the outside. There is a person inside the room responsible for turning them by hand....

Between the lines of Ibn Battuta’s brief descriptions, a careful reader will notice that his admiration for good examples of physical and administrative infrastructure expresses his belief that it is not merely the strength of the ruler that undergirds the stability and prosperity of the state, but also the extent to which the state’s infrastructure is developed. This is apparent not only in Ibn Battuta’s frequent notes of the state of roads, water, sanitation and hospitals, but also in his observation of what might be called “moral infrastructure”: the relationship of the local ‘ulama and the rich with society at large; the willingness of the local scholarly class to work with the government to achieve political stability. He comments on the governments’ encouragement of professionals, be they plasterers or goldsmiths or itinerant qadis like Ibn Battuta, to take their skills where they would; on the seemingly endless spirit of charity he found in the giving of alms and the support of waqfs and free madrasas and hospitals for all classes. All this moral infrastructure drew from a single well: the concept of ‘umma. |

Several points are notable about Ibn Battuta's descriptive accuracy. First, he appears to have regarded reportage in terms of information that might prove useful to others: The Door of the Hours served as a timekeeper for commerce. Second, he had a sense of significant detail: The number of public witnesses in the notaries' stalls testifies to a society in which bonded word and accurate memory are almost one and the same. When Ibn Battuta memorized the Qur'an, he embraced the collective assumption of the time that the mind can be relied on for accuracy just as our era relies on writing and microchips. Thus, in his descriptions, he was doing for his world something like what satellite television does for ours. And finally, it is striking not only that we can almost smell the cooking fires and hear the mongrels he describes whining at the braised-meat stalls, but also that he appears to have so clearly understood how the common moments of daily life link us all, no matter in what place or time we live. In reading the Rihla in its full extent, we gain a humbling yet embracing sense of our own place within civilization's long endurance. Seven centuries lie between Ibn Battuta and us, yet his words collapse them until we can feel many of the same things that he does.

In Damascus, Ibn Battuta also had quite a bit to say about the waqfs:

The variety and expenditure of the religious eitdowments of Damascus are beyond computation. There are endowments for the aid of persons who cannot undertake the Hajj [such as the aged and the physically disabled], out of which are paid the expenses of those who go in their stead. There are endowments to dower poor women for marriage. There are others to free prisoners [of warj. There are endowments in aid of travelers, out of the revenues of which they are given food, clothing, and the expenses of conveyance to their countries. There are civic endowments for the improvement and paving of the streets, because all the lanes in Damascus have sidewalks on either side, on which foot passengers walk, while those who ride the roadway use the center. One day I passed a young servant who had dropped a Chinese porcelain dish, which was broken to bits. A number of people collected around him and suggested, "Gather up the pieces and take them to the custodian of the endowment for utensils." He did so, and when the endowment custodian saw the broken pieces he gave the boy money to buy a new plate. This benefaction is indeed a mender of hearts.

|

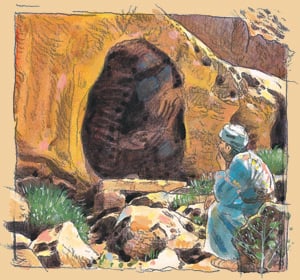

| In the tradition of earlier writers, whose descriptions of the Holy Cities had given rise to the literary genre of the rihla, Ibn Battuta systematically described Makkah’s sacred sites and his fulfillment of the rites of the Hajj—so systematically, in fact, that scholars believe parts of his descriptions of the Holy Cities to be based on or plagiarized from previous writers. Thus it is not certain exactly which sites he visited in 1326 during his first pilgrimage and which later, during his subsequent three pilgrimages, and at times he writes with such dry detachment that the reader cannot tell whether he personally visited a particular site at all. One of Makkah’s most famous sites, which he describes—and presumably did visit—is the cave on Mount Hira (Jabal Hira), “soaring into the air and high-summited,” where the Prophet Muhammad “used frequently to devote himself to religious exercises...before his prophetic call, and it was here that the truth came to him from his Lord and the divine revelations began.” Those revelations became the Qur’an. |

Such an esoteric endowment as one to replace broken utensils bespeaks a broad definition of charity and implies broad support for it. Indeed, of Damascus's 171 waqfs, Ibn Battuta reports, ten were endowed by the sultan, 11 by court officials, 25 by merchants, 43 by members of the 'ulama, and 82 by military officials. Ibn Battuta sheltered at waqfs during hardship periods and in outlying towns and cities—although he much preferred the better-appointed courts of local rulers.

ith the new moon of the month of Shawwal, it was from Damascus toward Madinah, and thence to Makkah, that Ibn Battuta turned. The 1350-kilometer (820-mi), 45- to 50-day camel caravan plod took an inland route along the west coast of the Arabian Peninsula, through the region known as the Hijaz, where the semi-desert littoral of the Red Sea rises abruptly inland to the high plateau of the Arabian Desert. The peaks topping 3700 meters (12,000') were the highest Ibn Battuta had seen since the Atlas Mountains of his native Morocco. Sprinkled lightly here and there were oases, and the caravan was strategically routed to pass through them, sometimes pausing overnight, sometimes remaining for several days. Ibn Battuta recalled the sequence of oases vividly: Dwellers in one, he said, named "The Bottom of Marr," luxuriated in "a fertile valley with numerous palms and a spring supplying a stream from which the district is irrigated, whose fruits and vegetables are transported to Makkah." There was not enough soil or water for grains, so the oasis dwellers cultivated dates, peaches, apricots, pomegranates, lemons, oranges, and figs. Some of these dried well in the piercing sun and air "as clear as sparkling water" and were staples of the desert diet.

ith the new moon of the month of Shawwal, it was from Damascus toward Madinah, and thence to Makkah, that Ibn Battuta turned. The 1350-kilometer (820-mi), 45- to 50-day camel caravan plod took an inland route along the west coast of the Arabian Peninsula, through the region known as the Hijaz, where the semi-desert littoral of the Red Sea rises abruptly inland to the high plateau of the Arabian Desert. The peaks topping 3700 meters (12,000') were the highest Ibn Battuta had seen since the Atlas Mountains of his native Morocco. Sprinkled lightly here and there were oases, and the caravan was strategically routed to pass through them, sometimes pausing overnight, sometimes remaining for several days. Ibn Battuta recalled the sequence of oases vividly: Dwellers in one, he said, named "The Bottom of Marr," luxuriated in "a fertile valley with numerous palms and a spring supplying a stream from which the district is irrigated, whose fruits and vegetables are transported to Makkah." There was not enough soil or water for grains, so the oasis dwellers cultivated dates, peaches, apricots, pomegranates, lemons, oranges, and figs. Some of these dried well in the piercing sun and air "as clear as sparkling water" and were staples of the desert diet.

Although the journey was arduous, there was little fear of getting lost: The way was visibly worn by the sandals of all the moveable world of that age: traders, pilgrims, servants, poets, camel-tenders, menders, soldiers, singers, ambassadors, clerks, physicians, coiners, architects, stable-sweepers, scullery boys, waiters, legalists, minstrels, jugglers, beekeepers, artisans, peddlers, shopkeepers, weavers, smiths, carters, hawkers, beggars, slaves and the occasional cutpurse and thief. Under way for six to seven weeks, the Hajj caravan was a small city on the hoof, with its own kind of cruise-ship economy, which always included several qadis for the resolution of disputes; imams to lead prayers; a muezzin to call people to prayer and a recorder of the property of pilgrims who died en route. That year, Ibn Battuta's caravan was protected from bandits by Syrian tribesmen, and he was befriended by a colleague, another Maliki qadi, in the genial and collegial fraternity of the road.

Ibn Battuta's account of Madinah fills 12 pages. Much of it is a detailed history and description of the Prophet's Mosque and other sites; the rest consists of anecdotes he heard from those he met, which give us vivid impressions of life in the desert. According to one of these, a certain Shaykh Abu Mahdi lost his way amid the tangle of hills surrounding Makkah. He was rescued when "God put it into the head of a Bedouin upon a camel to go that way, until he came upon him...and conducted him to Makkah. The skin peeled off his blistered feet and he was unable to stand on them for a month." Other tales are set in places from Suez to Delhi, and it was in settings like this that the 22-year-old Ibn Battuta's imagination was surely stimulated.

Our stay in Madinah the Illustrious on this journey lasted four days. We spent each night in the Holy Mosque, where everyone engaged in pious exercises. Some formed circles in the court and lit a quantity of candles. Volumes of the Holy Qur'an were placed on book-rests in their midst. Some were reciting from it; some were intoning hymns of praise to God; others were contemplating the Immaculate Tomb [of Muhammad]; while on every side were singers chanting the eulogy of the Apostle {Muhammad], may God bless him and give him peace.

At Dhu al-Hulaifa, just outside Madinah, the hajjis changed from their weather-worn caravan clothes into the ihram, the two-piece white garment which symbolically consecrated their entry into the Holy City of Makkah. Once in the ihram, the Muslim's behavior was expected to be a model of piety, and the spiritual aura of Makkah reinforced that expectation.

I entered the pilgrim state under obligation to carry out the rites of the Greater Pilgrimage...and [in my enthusiasm] I did not cease crying, "Labbaik, Allahumma" ["At Thy service, O God!"] through every valley and hill and rise and descent until I came to the Pass of 'Ali (upon him be peace), where I halted for the night.

![Nowhere in the 14th-century world was the mix of people more diverse than in the busy streets of Makkah, for pilgrims often financed their journeys by trade in the city’s markets before and after the days of the annual Hajj. Ibn Battuta found a convivial civic spirit: “The citizens of Makkah are given to well-doing, of consummate generosity and good disposition, liberal to the poor...and kindly toward strangers.... When anyone has his bread baked [at a public oven] and takes it away to his house, the destitute follow him and he gives each one of them whatever he assigns to him, sending none away disappointed.... The Makkans are elegant and clean in their dress, and as they mostly wear white their garments always appear spotless and snowy. They use perfume freely, paint their eyes with kohl, and are constantly picking their teeth with slips of green arak-wood.”](images/part1/BATTUTA_8.47307.jpg) |

| Nowhere in the 14th-century world was the mix of people more diverse than in the busy streets of Makkah, for pilgrims often financed their journeys by trade in the city’s markets before and after the days of the annual Hajj. Ibn Battuta found a convivial civic spirit: “The citizens of Makkah are given to well-doing, of consummate generosity and good disposition, liberal to the poor...and kindly toward strangers.... When anyone has his bread baked [at a public oven] and takes it away to his house, the destitute follow him and he gives each one of them whatever he assigns to him, sending none away disappointed.... The Makkans are elegant and clean in their dress, and as they mostly wear white their garments always appear spotless and snowy. They use perfume freely, paint their eyes with kohl, and are constantly picking their teeth with slips of green arak-wood.” |

Had Ibn Battuta been a lone voice in that unwatered wilderness, his words would have been lost on the wind. But he wasn't. Although he never mentions how many may have been with him in the caravan, it was likely to have been several thousand, for the pilgrimage must be performed in one specific 10-day period, and the sense of culmination and community pilgrims feel is part of what gives the Hajj its unique power.

Ibn Battuta described the Great Mosque:

We saw before our eyes the illustrious Ka'ba (may God increase it in veneration), like a bride displayed on the bridal chair of majesty and the proud mantles of beauty.... We made the seven-fold circuit of arrival and kissed the Holy Stone. We performed the prayer of two bowings at the Maqam Ibrahim and clung to the curtains of the Ka'ba between the door and the Black Stone, where prayer is answered. We drank of the water of the well of Zamzam which, if you drink it seeking restoration from illness, God restoreth thee; if you drink it for satiation from hunger, God satis fieth thee; if you drink it to quench thy thirst, God quencheth it.... Praise be to God Who hath honored us by visitation to this Holy House.

Ibn Battuta allots some 58 pages to description of the Ka'ba, the Haram, or sacred enclosure, around it, the city of Makkah itself, its surroundings, the details of the Hajj prayers and ceremonies, the character of the people and the traditions in the hearts of Muslims from all over Dar al-Islam. So important is Makkah that it seems that no detail, be it the interior of the Ka'ba or the provisioning of the bazaars or the forms of worship in the Haram, seems lost on him. Although his account has the tone of something partly received and partly felt, few documents have ever painted such a multicolored canvas of Makkah.

In reading the section devoted to Ibn Battuta’s first Hajj, some questions about authorship may arise in the mind of the careful reader of the Rihla. Parts of the descriptions of the Holy Cities differ distinctly in style and vocabulary from descriptions elsewhere in the work. (Similar questions arise about his later descriptions of Yemen and, most notably, China.) For example, Ibn Battuta begins his description of the minbar (pulpit) of the Prophet’s Mosque with a tale that a palm tree whimpered for the Prophet “as a she-camel whimpers for her calf” when he stopped leaning on it to go off and preach, whereupon Muhammad embraced the tree and it stopped its lamentation. Then he launches into an account of the construction of the minbar that reads like an art-historical dissertation. Scholars of the Rihla have shown with fair certainty that some of Ibn Battuta’s passages were—shall we say—creatively redistributed from a similar travel account penned by the Andalusian traveler Ibn Jubayr a century earlier. Yet this plagiarism, as we would regard it today, may well not have been Ibn Battuta’s doing, for the traveler’s scribe, Ibn Juzayy, trained as a court poet, would have felt a certain obligation to embellish Ibn Battuta’s recitations so the final product should be of a literary standard suitable for its royal patron, the Marinid sultan Abu ‘Inan of Fez. We have no way of knowing whether Ibn Battuta was aware of these improvements or not. |

Even so, there was the rest of the world and a lifetime of footsteps ahead. Makkah's feast of harsh natural scenery, global trade patterns, sharp mercantile acumen and abiding religious faith—all spiced with languages and dialects from Sudanese to Sindhi—no doubt whetted the young jurist's appetite for more. But unlike most pilgrims, who returned from their Hajj to their home cities and villages, Ibn Battuta did not set out westward for Tangier. He does not say why. Perhaps it was a spirit of youthful adventure; perhaps it was the memory of Burhan Al-Din's prognostication, back in Alexandria, that he would one day travel to India and China; perhaps it was word from others that jurists like himself might find work in remote places that were eager to receive scholars with more than local credentials.

Scholar Ross E. Dunn describes this significant juncture in Ibn Battuta's career in his 1986 book The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: "When he left Tangier his only purpose had been to reach the Holy House,...[but] when he set off for Baghdad with the Iraqi pilgrims on 20 Dhu al-Hijja, one fact was apparent. He was no longer traveling to fulfill a religious mission or even to reach a particular destination. He was going to Iraq simply for the adventure of it."

Setting a precedent he was to follow throughout his travels, however, Ibn Battuta did not take a direct route: Across the Arabian Peninsula's deserts, he looped through southern Iran and ventured north to Tabriz in southern Azerbaijan. It was a new year, 1327, when he entered the great walled city on the Tigris now called Baghdad.

|

Douglas Bullis is a researcher and writer who specializes in the Arab and Asian Muslim worlds. He divides his time between Southeast Asia and India, and can be reached at AtelierBks@aol.com or douglasbullis@hotmail.com. |

|

Norman MacDonald has illustrated more than 25 articles for Aramco World. He lives in Amsterdam, and became a grandfather while carrying out the present assignment. |